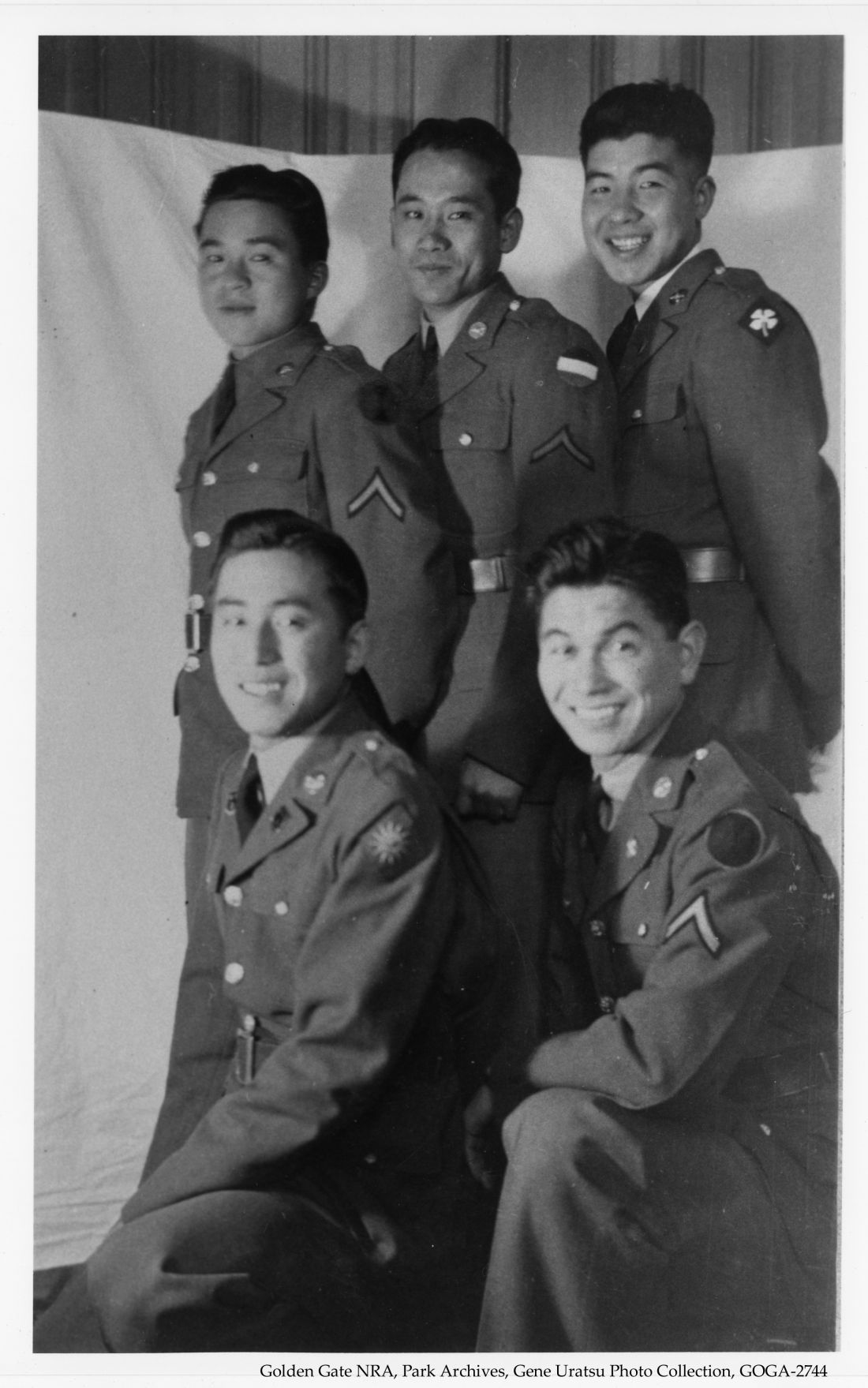

In May of 1942, 45 Japanese American students graduated from the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) school in the Presidio. They were the first class of a new program--in the history of the United States military there had never been a foreign language intelligence course. This experimental program turned out 6000 graduates between the years 1941-1946. According to General Charles Willoughby, the MIS Linguists were responsible for ending the war two years early and saving many thousands of lives. They would also help to rebuild Japan during the U.S. occupation after World War II ended.

In May of 1942, 45 Japanese American students graduated from the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) school in the Presidio. They were the first class of a new program--in the history of the United States military there had never been a foreign language intelligence course. This experimental program turned out 6000 graduates between the years 1941-1946. According to General Charles Willoughby, the MIS Linguists were responsible for ending the war two years early and saving many thousands of lives. They would also help to rebuild Japan during the U.S. occupation after World War II ended.

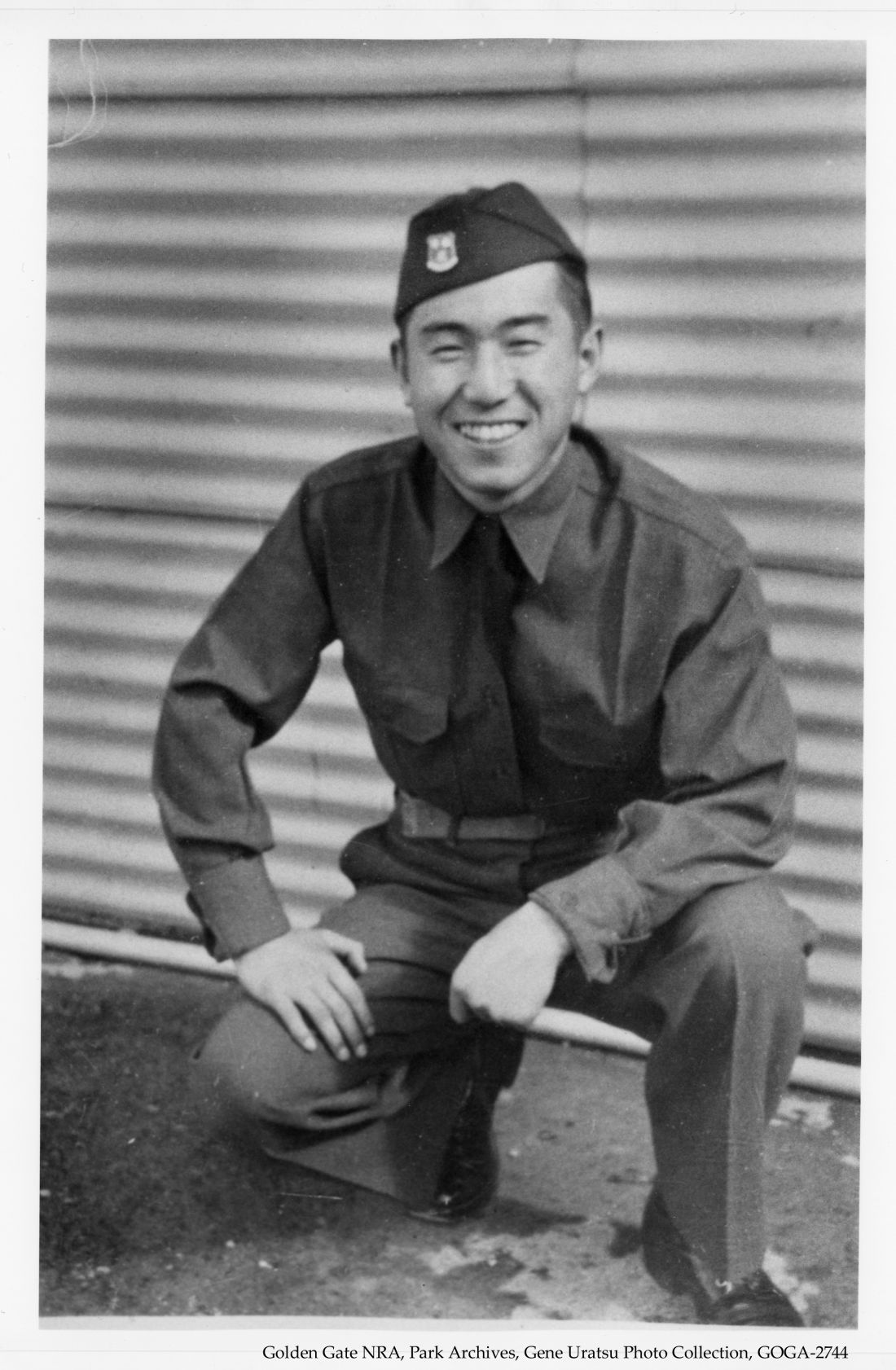

Several collections at the Golden Gate National Recreation Area's Park Archives and Records Center tell the stories of these Japanese Americans who risked their lives and served their country, showing great heroism even while being mistrusted by many of their commanders, fellow soldiers, and other citizens they had sworn to protect. These collections deepen our understanding about Japanese American military service before and after the events of Pearl Harbor.

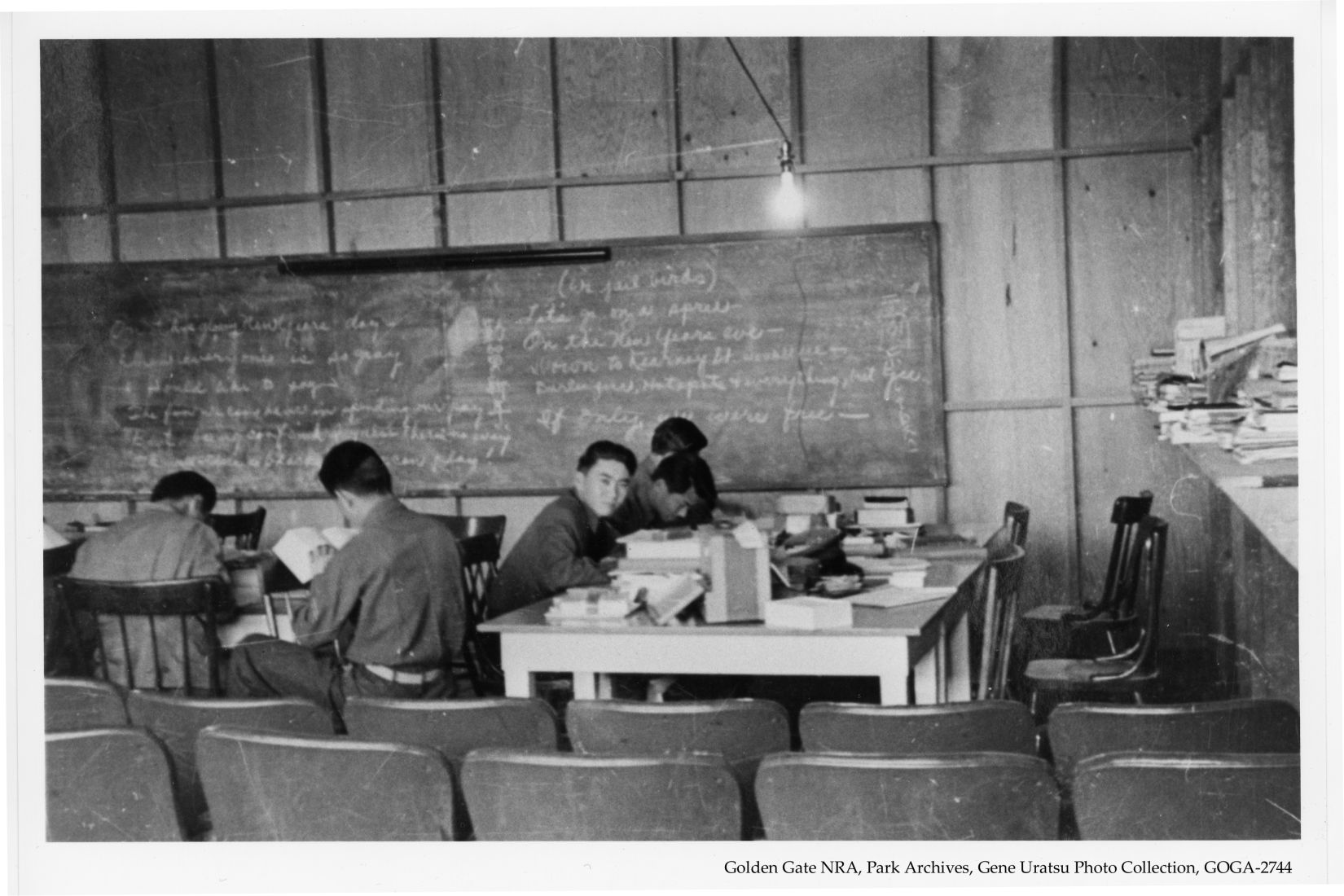

The intelligence school was a new venture, but not a shiny one. The building that housed the school was a dilapidated airplane hangar on Crissy Field with crude furniture. Shigeya Kihara, one of the MIS teachers, described it as an “abandoned, empty, unpainted, crusty-looking corrugated tin building.” Just weeks before the students’ arrival, carpenters were working to set up the three classroom walls and make the space habitable.

Although all the Nisei (first generation Japanese American) students already spoke some Japanese, the Army’s school introduced them to the more specialized terminology that they would need. The teachers, none of whom had ever taught Japanese or had any training as teachers, were only given two weeks to prepare texts and develop a curriculum. According to Shigeya Kihara, this included terminology for every Japanese military branch including their structures, equipment, and vehicles. Since both the United States and Japan were developing this terminology and technology during the war, the curriculum was revised as new material was gathered.

Although all the Nisei (first generation Japanese American) students already spoke some Japanese, the Army’s school introduced them to the more specialized terminology that they would need. The teachers, none of whom had ever taught Japanese or had any training as teachers, were only given two weeks to prepare texts and develop a curriculum. According to Shigeya Kihara, this included terminology for every Japanese military branch including their structures, equipment, and vehicles. Since both the United States and Japan were developing this terminology and technology during the war, the curriculum was revised as new material was gathered.

As time went on, the lessons also included Japan’s geography, interrogation techniques, and different writing styles such as sosho. Sosho, which translates to grass writing, was an informal writing style taught in Japan, similar to cursive. Japanese soldiers kept diaries written in sosho, and often recorded lots of details, along with their observations. Therefore, it was essential for MIS workers to be comfortable translating these documents.

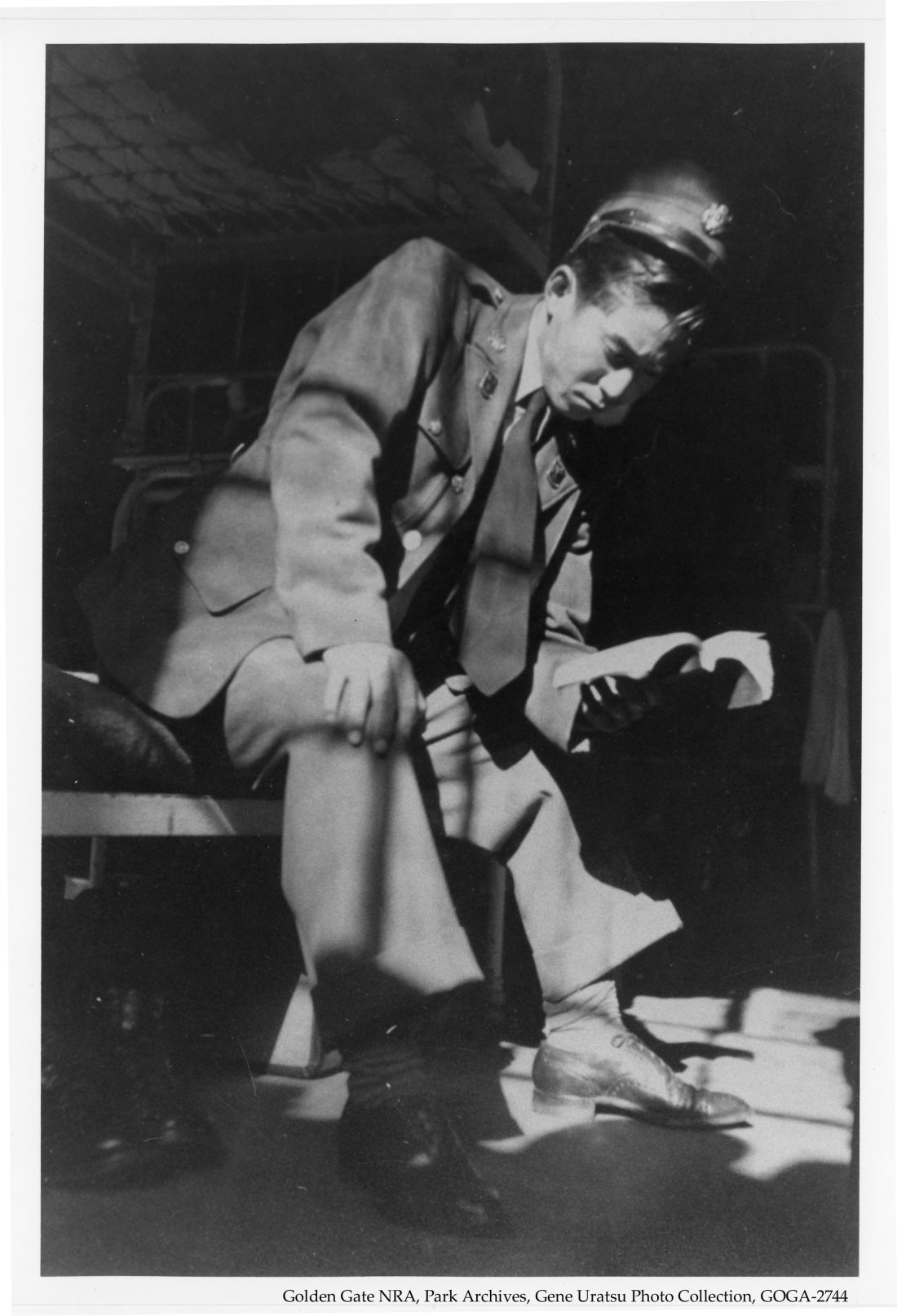

The school day was 8 hours long, and included two hours of study in the evening. Assessments were given weekly, and students who fell behind were dropped from the program. After lights out at 10pm, students could regularly be found studying in the bathroom, the only place where the lights were kept on in the building.

The school day was 8 hours long, and included two hours of study in the evening. Assessments were given weekly, and students who fell behind were dropped from the program. After lights out at 10pm, students could regularly be found studying in the bathroom, the only place where the lights were kept on in the building.

Before Pearl Harbor, the Nisei students would go into Chinatown and Japantown on weekends. After the December 7th attack, they were confined to the Presidio and questioned if they tried to go anywhere. Nisei were reclassified in the draft from 1-A, unrestricted military servicemen, to 4-C, designating them as aliens, or having dual nationality. Although this was later reversed, the designation kept many Nisei from joining the military during WWII.

Executive order 9066 was signed on February 19, 1942 and mandated that people of Japanese descent be relocated throughout the country. Japanese people were forced to sell businesses, homes, and other property, often at significant losses. MIS students and faculty in the Presidio were not given leave to assist their families during this chaotic period.

In May 1942 after graduating from the MIS program, 35 students were sent overseas, mostly without the promotions they had been promised before entering the program. Their new commanding officers often had little trust or use for them, and many were assigned to driving Jeeps and similar duties. However, this didn’t last long. After prisoners and documents began to be captured, the Nisei linguists were able to utilize their language skills. Their competency and intelligence value soon drove demand for more linguists, ensuring the continued success of the MIS program. After graduating the first class from the MIS school at the Presidio, the program was relocated to Camp Savage in Minnesota. The school continued to grow, and the last class in 1946 had an enrollment of about 2000 students, employing almost 170 instructors.

In 1994, Shigeya Kihara said the contributions of the Nisei linguists were relatively unknown comparatively to the 442nd, an infantry unit composed primarily of Nisei, which was the most decorated unit of its size in military history. This is partially due to the operation’s secrecy, since it remained classified until the 1970s, but it was also because of the discrimination that Nisei soldiers faced before, during, and after the war. And yet, despite the discrimination, the Nisei linguists showed immense bravery and sacrifice during a time of suspicion and palpable racism. Thomas Sakamoto credits Nisei dedication to the American cause in World War II to Japanese beliefs about honor and sacrifice that were instilled in them as young people by their immigrant parents. By being true to their Japanese heritage and culture, they proved they were Americans.

____

____

If you would like to learn more about the Nisei linguists, you can explore their collections in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area Archive through these collections: GOGA 35228, the Thomas Sakamoto collection, GOGA 09728 the Gene Uratsu Photo Collection, or GOGA 18989 the Shigeya Kihara Oral History. The National Japanese American Historical Society also maintains the Military Intelligence School building 640 in the Presidio. You can visit their website for more information: https://www.njahs.org/

Additional information for this post was gathered from:

Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service During World War II by James C. McNaughton, published by the Department of the Army, Washington D. C., 2007