Xunaa Shuká Hít in Glacier Bay

The cooperative venture between the Huna Łingít and the National Park Service stands proudly in Bartlett Cove.

People in Glacier Bay

Human History of Glacier Bay

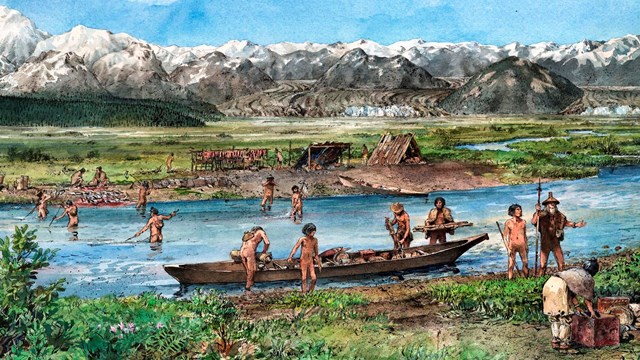

Huna Łingít

Indigenous People of Glacier Bay

Commercial Fishing History in the Park

History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay

A Land Reborn

Administrative History of Glacier Bay A journey through Glacier Bay is more than a journey through geography. It's a journey through time. We begin in the modern age and finish in the ice age, traveling north from the forested lower bay to the rocky, icy upper bay (roughly 65 miles/105km). We pass through hundreds of bold changes and subtle transitions where plants and animals pioneer new ground and surprise even the most seasoned observers of nature. A bear crosses a glacier. A moose swims an inlet. A seedling spruce emerges from granite, reaching for the sky. Life is tough and tenacious here. No wonder Glacier Bay holds powerful stories, and attracts scientists, preservationists, and travelers from around the world. One of those scientists was a plant ecologist from Minnesota, a quiet man with an easy smile who studied relationships. He came to Glacier Bay in 1916, and over several decades returned many times to make careful observations. His name was William S. Cooper. What he found so inspired him—a wild land, undefiled, untamed, returning to life in the wake of glacial recession—that he shared his findings with colleagues at the Ecological Society of America. Might it be possible, they asked, to preserve Glacier Bay? To keep it wild; as a place where nature can unfold in ways that will teach and enlighten us forever? Cooper knew the history of Glacier Bay. The Huna Łingít occupied the area for countless generations, living in the shadows of glaciers, prospering from the bounty of the land and sea. Captain George Vancouver had sailed the area in 1794, and created a rough map that showed the bay filled with a single great glacier. Eighty-five years after Vancouver, naturalist/preservationist John Muir had visited the bay by canoe, and found the glacier receding as fast as a mile per year. Muir wrote about Glacier Bay with such lyrical heart—his words like music—that he changed America's national perception of Alaska from one of daunting cold to enchanting beauty. Like the little plants he studied, William Cooper was tough and tenacious. Like John Muir, he found in Glacier Bay a power that inspired him to become something more than what he had been. He wrote letters, made personal appeals, and suffered criticism. No great act of public lands conservation is made without a fight. It paid off on February 26, 1925 when Glacier Bay became a national monument. Fifty-five years later, President Jimmy Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act that created Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve on December 2, 1980... it would have made William Cooper smile and John Muir sing.

Pioneer ecologist William S. Cooper of the University of Minnesota conducted plant succession studies beginning in 1916, and was instrumental to the protection of the Glacier Bay area.

Glacier Bay Historic Resources Study

A Land Reborn

Navigating Troubled Waters

Gustavus Historical Archives and Antiquities |

Last updated: September 8, 2025