|

Caribou and People | Caribou Skin Clothing | Caribou Skin Tents |

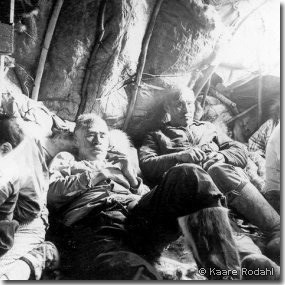

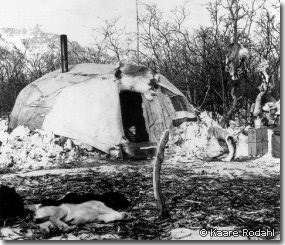

© Kaare Rodahl Inside the tent, women pushed thick moss tightly against the bottom edge to seal out drafts. They gathered fresh willow branches and laid them down to make a soft and fragrant floor. The sleeping area had three layers of skins: first, a floor covering made from unscraped bull caribou hides; next individual mattresses, each made from a young fall bull caribou hide; and finally soft, carefully tanned summer calf or cow skins for warm blankets. In the daytime, people rolled their blankets and mattresses up against the walls to use as back rests. A lamp that burned seal oil or caribou fat provided heat and light—both essential during the long darkness and cold of the arctic winter. For cooking, a fire was built outside the tent and the food brought inside to eat. Rocks heated in the fire could also be taken inside for additional heat.

© Kaare Rodahl In summer, the thickly furred caribou hide sheathing was stored and only the lighter, rainproof outer layer was used. During the warm months, people camped on the open, breezy tundra away from the willow thickets, which often swarmed with mosquitoes. For countless generations, the traditional itchalik provided a secure and comfortable house for Nunamiut people on the move, but this began to change when modern materials became available. After they acquired wood-burning stoves, they sewed a sheet metal collar into the sheathing, which held the stove pipe and kept it from burning the hides. Eventually, people obtained gas-burning Coleman stoves; kerosene or gasoline lanterns replaced the old lamps that burned animal oils; and canvas displaced the waterproof outer layer of caribou hide sheathing. Still later, dome tents gave way to canvas wall tents, although these were sometimes lined with caribou skins for added warmth; and even today, people sleep on caribou hide mattresses in remote hunting and fishing camps.

NPS Photo/Aaron Wilson After the Nunamiut people settled permanently in the village of Anaktuvuk Pass, they lived in sod houses rather than caribou hide tents, and these in turn have been replaced by frame houses.

But reminders of an older time are still scattered across the land. Around the bottom edges of their itchalik homes, ancestral Nunamiut people laid chunks of sod, heavy rocks, or banked-up snow to hold the caribou sheathing fast against winter gales and frigid temperatures. Today, stone tent rings—some nearly 5,000 years old—can be seen in many places within Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve. They are eloquent reminders that modern visitors to the Brooks Range walk in the footsteps of people who have made these arctic mountains a homeland for generations far beyond memory. Caribou and People | Caribou Skin Clothing | Caribou Skin Tents | |

Last updated: December 1, 2021