|

Caribou and People | Caribou Skin Clothing | Caribou Skin Tents |

NPS photo by Jeff Rasic Throughout the history of Nunamiut Eskimos living in the Brooks Range, success in caribou hunting was critical to survival. People frequently moved their encampments to follow the caribou and intercept their migrations. When caribou were plentiful, there was meat and fat in abundance, hides for clothing and shelter, sinew for thread, and rawhide for lashing. But when caribou were scarce, the inland Eskimos could face hardship, hunger, and even starvation.

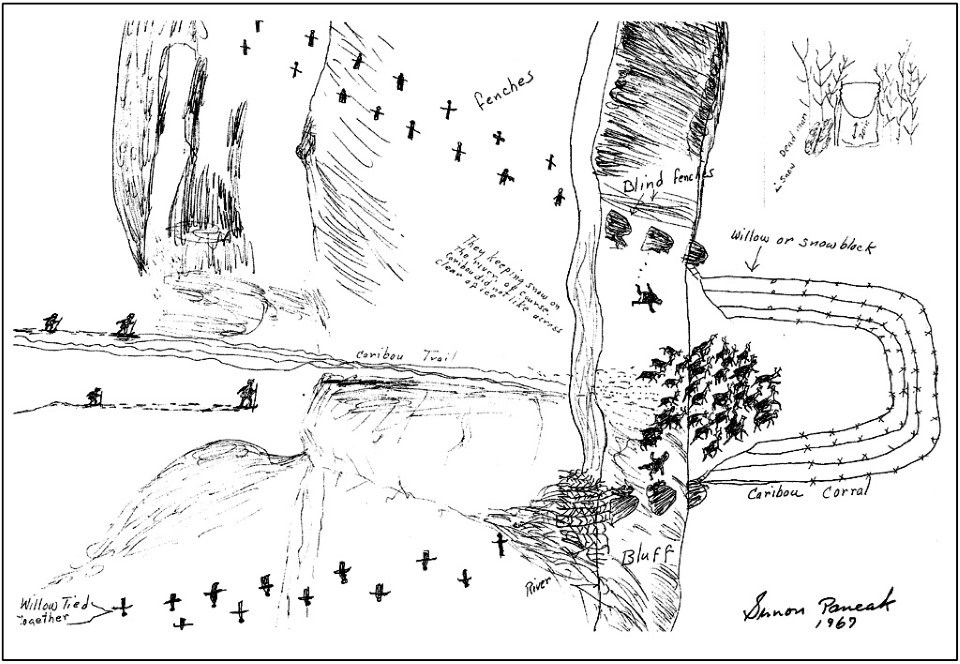

Over the passage of many generations, Nunamiut people closely observed the migratory patterns of caribou and learned every detail of the landscape. They understood how local topography channels the long skeins of caribou coming from the north in fall or the south in spring. And they came to know caribou so well that they could enter the animals’ minds, predicting where they would go and how they would react in a wide range of circumstances. Hunters learned that the movement of caribou could be influenced by something tall, erect, and human-like on the open tundra. Using this knowledge, they made stone people (iñuksuk), by standing elongated stones on end or by piling up rocks and topping them with willow branches and bits of cloth that fluttered in the wind. Nunamiut Eskimos arranged these scarecrow figures in two gradually converging rows, sometimes up to five miles long. When a herd of caribou approached, the iñuksuit (plural for iñuksuk) helped to funnel them into a lake, a river, or a corral where they could more easily be killed.

Simon Paneak illustration In winter and summer, the larger bands broke up into small family groups that dispersed widely, and Nunamiut men hunted caribou individually or with a few companions. Then, during the spring and fall caribou migrations, bands came together for the very important caribou drives. In places known for seasonal concentrations of caribou, the people or their ancestors had built lines of iñuksuit. As a herd of caribou approached, women, children, and elders who were not hunting moved in behind the animals, carefully driving them between the lines of scarecrows, and then urging them along until finally the herd entered the water. This was the moment the hunters had been waiting for—sitting in kayaks tucked out of sight against the lakeshore or under a concealing riverbank. Their specially designed inland kayaks (qayaq) were long and narrow, built for maximum speed. Once the caribou started swimming, hunters swiftly paddled after them, came up alongside, and killed the animals with spears.

Simon Paneak illustration Importantly, caribou do not sink like most other animals because their coats are made up of hollow hairs, with tiny pockets of air providing buoyancy. Hunters could get large numbers of caribou and then tow them ashore. Then everyone in the camp worked to butcher the caribou and preserve the meat, either by drying it in the open air or by freezing. In areas without suitable lakes or rivers, the drive line ended in a corral—a U-shaped fence made from willow poles and branches. Large rawhide nooses were hung in gaps between the willows, and caribou became snared as they tried to escape through the openings. Hunters then killed the animals with arrows or spears. Over the past century, these traditional weapons gave way to rifles, and Nunamiut hunters used the old drive lines less and less. Eventually the people left their nomadic camps and settled into the village of Anaktuvuk Pass. The communal drives ended before 1900, but in 1944, a shortage of bullets during World War II spurred Nunamiut hunters to resurrect the caribou lake hunt. Like a dream from the past, an ancient tradition was played out one last time as men in qayaqs, armed with homemade spears, sped across the water to intercept the swimming caribou. Caribou and People | Caribou Skin Clothing | Caribou Skin Tents | |

Last updated: April 10, 2017