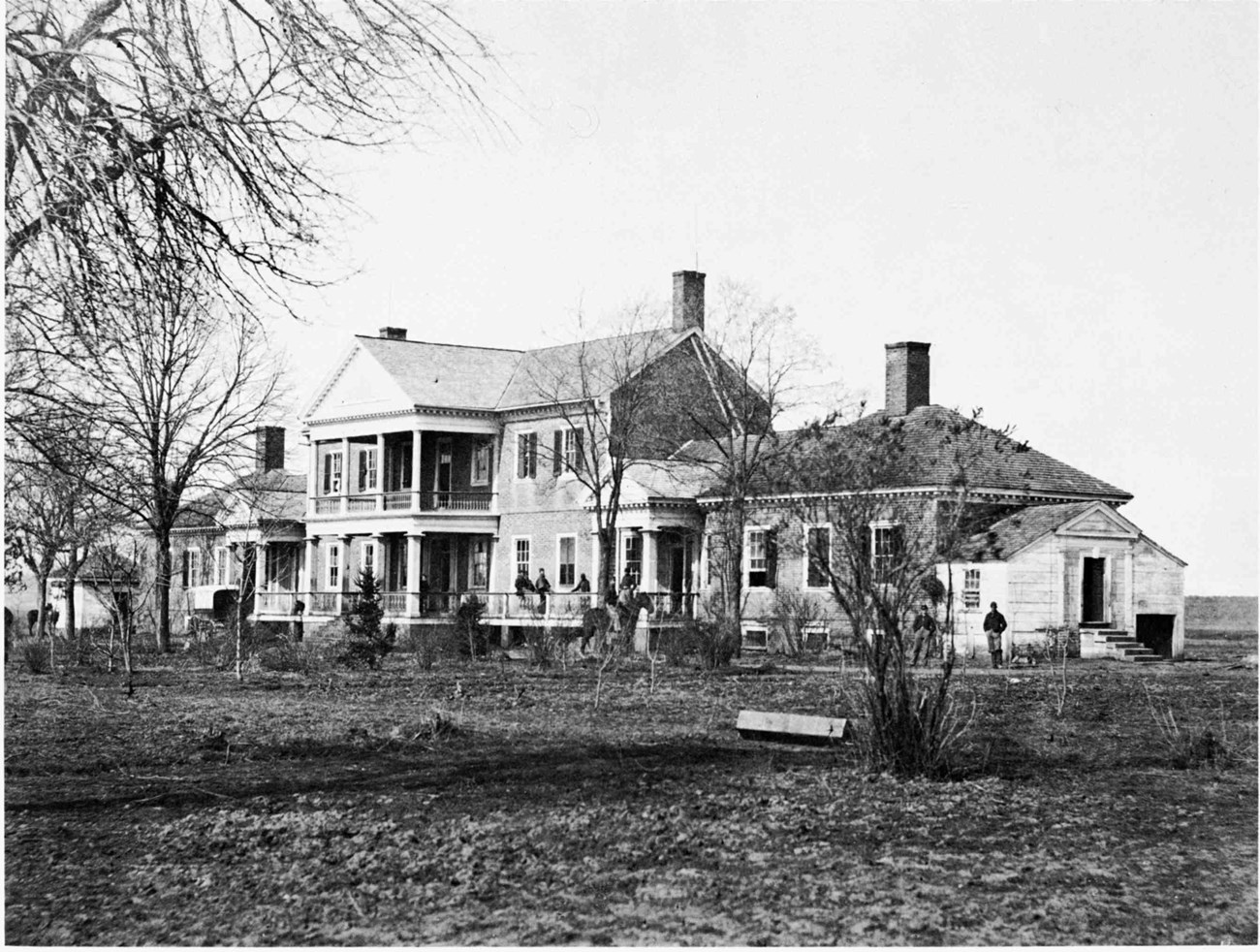

NPS Image The practice of manumission was a controversial one in the antebellum South, and the will was contested rather than executed according to Hannah Coalter’s wishes. Manumission was a form of freeing slaves, but in the Coalter case, slaves were not permitted to live freely in the community they knew, but rather they had to chose to relocate far away or stay enslaved in Virginia. One of the most controversial aspects of this kind of manumission was that enslaved people were given the responsibility to make their own choice. Not only was the manumission of slaves a cause for concern, but Hannah’s beloved daughter and heir was believed to have impaired vision, hearing and mental disabilities. She was not considered to be capable of managing the estate at Chatham. Hannah Coalter’s will was challenged by her brother-in-law, J. Horace Lacy, who saw the case through to the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. On May 24th, 1858 the court ruled that the “slaves remained in slavery” and that the legality of offering enslaved people a choice in their freedom nullified the entire will. This court case resolved shortly after the Supreme Court’s declaration that Americans of African descent were not citizens before the law in the landmark case Dred Scott vs. Sanford, and serves as an example of national decisions being carried out at the local level. As a result, Chatham and the population of enslaved people were sold together at public auction to the Lacy family.

NPS Image Beyond this article there is no more information or evidence to show that the slaves were given this manumission choice. It is entirely possible that most made the choice to stay at Chatham; freemen after the war struggled to establish new lives and often returned to work for their former masters. There are, however, several factors that cast doubt on the unanimous consent of Chatham’s residents to stay enslaved. First, Hannah Coalter’s manumission provisions would result in the loss of capitol for her heirs and executors. Importing enslaved people had long since been outlawed, which increased the value of the population of slaves in the antebellum South. The number of people that Coalter enslaved could have been worth over $50,000, which was too high a value to easily let go. Secondly, there is evidence that not all people desired to remain in slavery under J. Horace Lacy. Ellen Mitchell, a laundress at Chatham, was one of the ninety-two slaves sold at auction to Lacy. After the sale, Lacy removed most of those enslaved people to his estate at Ellwood and another in Louisiana to work. Ellen Mitchell reportedly refused to comply with Lacy’s plan and negotiated an arrangement where she travelled to the Northern free states to raise money and purchase freedom for herself and her children. After three months of travel, Ellen successfully raised over $1,000 and left Chatham with her children to live in Ohio. Ellen’s story strongly supports the theory that Hannah Coalter’s slaves were not, in fact, given the opportunity to declare their freedom and instead were kept in slavery and tied to the estate. Text by Maureen Lavelle |

Last updated: September 7, 2021