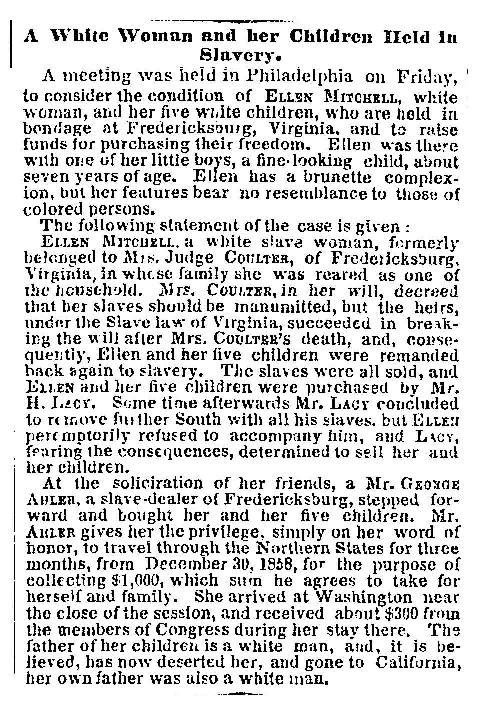

New York Times Ellen Mitchell With the death of Hannah Coalter in 1857, the fate of her slaves was thrown into turmoil. Coalter attempted to manumit her slaves upon her death, but she did so in a very unique way. In her will, Coalter's slaves were given the option of choosing one of her living relatives to be their new owner or immigrating to Liberia or "any other free state or country". This unusual stipulation was challenged in court by Coalter's heirs, and eventually nullified on the grounds that slaves were not citizens, and could not make decisions about their own status as property. As a result, the sale of Coalter's plantation, Chatham, included most of her former slaves who were now tied to the property. The estate was purchased at auction by Coalter's brother-in-law, J. Horace Lacy, who decided to send most of his new slaves to Louisiana to work on another of his plantations. One of the slaves included in the sale of Chatham, a young woman named Ellen Mitchell, reportedly refused to comply with this arrangement. It is unclear exactly why Ellen took this risk, but perhaps she feared being separated from her five children. Ellen was a unique woman among the slaves of Chatham for several reasons. She was literate, which was a criminal offense for slaves in the antebellum South, and her complexion was very light. Slavery was premised on the inferiority of other humans based on race, but those descended from multi-racial parents were often not easily cast as one race or another. Ellen's children were fathered by a white man, and were characterized as white. Ellen's literacy and light skin posed a potential hazard to Lacy, as she could spread dissent among his other slaves. It is possibly due to these factors that, rather than punishing Ellen for challenging his decisions, J. Horace Lacy agreed to let her buy freedom for herself and her children. Ellen was allowed to travel north to several cities, and was given three months to raise $1,000 dollars. She spent March of 1859 traveling to Philadelphia, New York City and Washington D.C., where she met with abolitionist groups and spoke about her situation. She met with friends and relatives of Hannah Coalter who assisted her during her travels, and contributed funds toward her goal. Within thirty days, Ellen had raised well over $1,000 and returned to Fredericksburg to complete the purchase. On April 2nd, 1859, Ellen Mitchell and her five children were freed by a deed of manumission. In a letter to Hannah Coalter's neice, Ellen wrote that after the sale, Lacy allowed her to also take her elderly mother, as aged slaves were not valued highly in a society that legally categorized them as property and not people. Ellen eventually moved her family to Cincinnati, Ohio, where she worked as a laundress. Ellen Mitchell's journey to freedom was not unusual among slaves- many worked hard to purchase freedom for themselves or their families. However, Ellen certainly represents a unique group of slaves who wielded the power of the growing abolitionist movement to change their fortunes for the better. Text by Maureen Lavelle |

Last updated: July 16, 2016