NPS Unearthing the Past, Discovering TodayIn the decades after 1867, when the Army and passing steamboats' crews razed the post, scant evidence of Fort Union remained visible above ground: ceramic shards, scattered metal scraps, and broken glass. Farmers, fur trade historians, and the residents of Mondak, Williston, and other nearby communities nonetheless knew where Fort Union had stood: atop the high riverside gravel bed observed in 1805 by the passing Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Some of these individuals recognized the site's national significance, while others didn't. For most, the demands of everyday life—of planting and harvesting, of supporting families—consumed their attention. By the early 1900s, however, farmers who had started to plow and plant the site's surrounding fields often brought to the surface tell-tale signs of a vast but buried harvest of artifacts: glass beads, shell casings, buttons, the rusted remnants of hand-forged tools, building materials, clay pipe fragments, and bison and human bones. As the years passed, area residents and history enthusiasts explored the post's grounds, one historian wrote in 1938, and collected what they found for personal collections: "old hinges, locks, harness buckles, arrowheads, . . . , pieces of tools and other artifacts." In the meantime, because increased automobile use led to demands for more gravel-based roads, gravel mining commenced on the buried fort's west side, where today's parking lots are located.

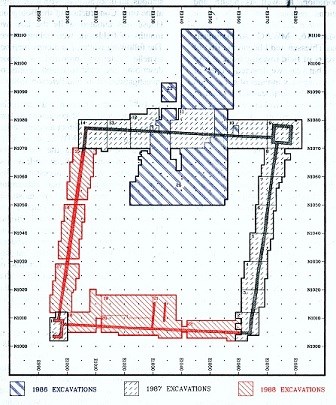

NPS / EDWARD HUMMEL By 1936, gravel miners had unearthed and undermined the surviving foundation of the old post's southwest bastion. This prompted area citizens, led by local women, to organize and raise money to acquire the site. Despite the Great Depression and the women's difficulty in raising needed funds, North Dakota two years later purchased 10.46 acres of land that encompassed the fort's remains. It was designated a state historic site. Then, in 1966, thanks in large part to the continued advocacy of local residents like Ben Innis and others, Congress passed legislation that established Fort Union National Historic Site. The reconstructed fort that visitors today tour wouldn't exist for another 25 years, however. What did the historic fort look like, how was it built, and from what materials? These and other questions had to be answered before an accurate reconstruction could be planned and built. That's why archaeologists arrived in 1968 to begin exploratory excavations. That summer, Jackson W. "Smokey" Moore sank a series of test trenches in an attempt to locate and identify the former post's various buildings. Once the Bourgeois House and palisade walls were located precisely, successive archaeologists excavated deeper.

NPS / MIDWEST ARCHEOLOGICAL CENTER Despite the resistance of some in the National Park Service, sufficient local support existed in 1986 to kick-start Fort Union's reconstruction. Thus, between 1986 and 1988, archaeologists focused on finding and recovering the architectural and other evidence needed to create an accurate reconstruction. During these three seasons, archaeologist William Hunt, Jr., led teams of students and volunteers in excavating and documenting the fort's original foundations. By the end of the 1988 field season, successive archaeologists beginning with Smokey Moore and their field crews had discovered an unexpected number of artifacts: more than one million, the vast majority of which archaeologists returned to the park after they had been cleaned and studied. "It's not what you find," the archaeologist David Hurst Thomas once wrote about archaeology, "it's what you find out." And that—what Fort Union's artifacts have made it possible for researchers and the public to learn—is the value and significance of the historic site's museum and archival collections. What professional, student, and volunteer excavators discovered and documented during the digs, the most extensive then undertaken by the National Park Service, revealed more than the historic foundations on which today's reconstruction stands. In combination with the business records, journals, and drawings produced by post employees and visitors, these artifacts and their associated archival records provide tangible evidence of the fur trade's history. What's you'll discover in following collections pages is but a sampling of what has been recovered to date. The stories these artifacts help flesh out allow us to learn about the post, the fur trade, and its employees and their families; the region's Native American peoples, and the natural and human-built environment in which they lived and worked.

NPS Pieces of bone, for instance, indicate what wild and domestic animals—bear, bison, wolves, dogs, and pigeons—the people hunted and traded for food and furs, while hardware like the padlock and hinge pictured above offer detailed clues about the fort's buildings and their construction. Arrowheads, guns and gun parts, knives, nails, the head from a pair of blacksmith's tongs, broken glass bottles and ceramic plates, and items such as buttons, thimbles, and beads, including the country's largest collection of trade beads—these all help us piece together and understand what individuals not much different from ourselves did and used to adapt to local conditions and the challenges presented by engaging in business with new and different peoples. To learn more about how the people at historic Fort Union met their day-to-day needs and survived, follow in their footsteps and visit today's trading post. While here, you can browse the museum exhibits, speak with a trader in the trade house, and watch blacksmiths work. |

Last updated: April 24, 2021