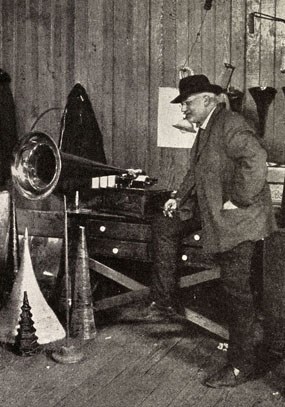

Theo Wangemann, a biography by Patrick Feaster Adelbert Theodor Edward Wangemann was born in 1855 with a family background in both music and industrial manufacturing. His paternal grandfather, Johannes Theodosius Wangemann, had served as a choirmaster and teacher in Demmin, Pomerania, and his father, Adalbert Theodor Wangemann, was a Berlin merchant specializing in paper and paper goods. During the 1870s, the family business centered on a factory and warehouse at Köpenickerstraße 98a, where Theo's elder brother succeeded his father as proprietor about 1876. Judging from the services the Wangemanns offered, Theo is likely to have participated in such tasks as the manufacture of envelopes and the embossing of monograms onto writing paper. Both of Theo's parents died in 1878, and in 1879 he and his elder brother emigrated to America. Theo first settled in the Boston area, where he seems to have continued in the paper business as a salesman or clerk. In 1884, he married Anna Blake, the daughter of a local paper merchant, and within a few months of the wedding he had moved to New York City, where he became a naturalized citizen. [Click here for more details on "Family background and early life".] In the spring of 1888, Theo Wangemann went to work for Thomas Edison, who was then busy developing his new wax cylinder phonograph. Wangemann's job, as he later expressed it, consisted of "[e]xperimenting on phonograph recording with a view of making better musical records, vocal and instrumental."[1] It's still unclear exactly what qualifications had landed him this position. Years later, an obituary quoted one of his friends as saying that "every one knows Mr. Wangemann was an authority on acoustics, in his earlier years being an esteemed pupil of Helmholtz."[2] That's possible, but none of Wangemann's known professional activities before 1888 seem to have involved any special acoustic expertise. Still, he was musically talented, like his grandfather; his obituary in an official Edison publication stressed that he was "a skilled pianist, a fine musician and possessed an excellent musical education."[3] He also had experience with industrial processes, probably including the use of embossing presses, which might have resonated with Edison's aspirations for the mass-duplication of phonograph cylinders. The quest to develop musical recording techniques had borne fruit by May 11, 1888, when Edison invited the press to the laboratory for a first demonstration of his new wax cylinder phonograph as applied to instrumental music. Wangemann was presumably the "assistant" who "played airs from 'Evangeline' on the piano," which were promptly played back Wangemann's workplace in the laboratory was Room 13, where he had several assistants: "Walter Miller worked there during the entire time that I was there," he recalled, "and at times we had 5 or 6 more, from 2 to 5 boys there."[7] (Others besides Miller included Henry Hagen and Osgood "Nick" Wiley.) At first, the new phonograph was itself still in an experimental state, but a prototype went to England in June 1888, and this created a need outside the laboratory for good musical phonograms to be used in demonstrations, which it fell to Wangemann to fill on top of his strictly experimental work. One of the first American cylinders played overseas that summer was a cornet solo featuring him as piano accompanist,[8] I wish to mention to you privately that I notice on the end of all Wangemann's cylinders a peculiar musical trade mark - like this:

I think that on the end of an operatic selection particularly this musical trade mark is a little out of place.[11] The earliest Wangemann recording known to survive today is a cylinder of "The Pattison Waltz" as performed by Effie Stewart on February 25, 1889, and his distinctive "trade mark" can indeed be heard in the piano improvisation at the end. Although Wangemann was charged primarily with developing musical recording techniques, he also participated in other phonograph-related experiments, including a pioneering attempt to record live political speeches at a rally in Orange, New Jersey on October 25, 1888,[12] a recording session of December 1888 with the famous minstrel Lew Dockstader in which he served as "interlocutor" or straight man for the jokes,[13] and a test of the durability of a phonograph doll: "This doll lasted as near as I remember, about two weeks," he recalled, "when the ring was broken by the child throwing the doll down stairs."[14] Wangemann spent much of March and April 1889 away from the laboratory in Boston, where he had gone to record Hans von Bülow and other eminent musicians in concert,[15] and at least one cylinder from this visit is known to survive: a recording of a piano performance by Professor John Knowles Paine of Harvard University (EDIS 39836). That May, Wangemann opened a formal recording ledger, a step that coincided with the first official offering of musical phonograms for sale through the North American Phonograph Company.[16] This probably represented an effort to place formerly haphazard phonogram production on a more methodical footing. On June 15, however, Wangemann left the laboratory to his associates once again, this time going to France. As he later explained it, "The phonograph exhibit at the Paris Exhibition was reported to be poorly in comparison with the results shown in the Laboratory, and Mr. Edison sent me over there primarily to have the phonograph exhibit run as well as possible."[17] [Wangemann's trip to Europe is covered in the essay Prince Bismarck and Count Moltke Before the Recording Horn: The Edison Phonograph in Europe, 1889-1890, by Stephan Puille.] Shortly before Wangemann's return from Europe, Edison shut down the recording program at his laboratory on short notice, claiming that he had "allowed it to go on" only as a favor to the trade and that "the number of complaints that I have been asked to read lately has shown me very clearly that this business must be handled by some one who has more time to devote to it than I have."[18] As long as no viable means of mass-duplication could be found, the one-by-one manufacture of musical phonograms struck him as more trouble than it was worth. Wangemann continued to work in Edison's laboratory in some capacity until June 1890,[19] but then he was put in charge of a phonograph display at the Minneapolis Industrial Exposition from August through October.[20] Late in the year, he became affiliated with the New York Phonograph Company, possibly succeeding John English as its manager;[21] and he continued to work there through March 1893.[22] That January, when Alfred Tate wrote to Edison recommending that Wangemann's erstwhile assistant Walter Miller be put in charge of the North American Phonograph Company's revamped recording program, he added: The only other man at present in our employ who is in any way capable of taking charge of the Department is Wangemann, but it seems to me that he experiments too much. He does not seem to get results. This experimental work may be necessary, but if it is I would like to throw it entirely out of the hands of any one employed by the North Am. Phonograph Co. and into your Laboratory, where it belongs. Experiment and manufacture cannot be dovetailed without disaster. Walter Miller spoke very highly of a young man named Hagan [i.e., Henry Hagen].... Hagan is tractable and willing to follow out directions. Wangemann would, of course, want to run things his own way, so far as technical methods are concerned.[23] At this point, Wangemann abandoned the professional recording business for nearly a decade, but he continued experimenting, as he later testified: I had no connection with any Phonograph Company after the Spring of 1893, but always kept up making experiments of phonograph improvements in my own home, when my time permitted me to do so. For over two years, I kept one phonograph in Steinway Hall, 14th Street, and experimented there perhaps two or three times in an afternoon each week. Occasionally, I would make up a box of records and bring them out to Mr. Edison. I had in Steinway's the pleasure of recording a great many of the best musicians, both vocal and instrumental. [This was in] 1894, 1895, 1896. Even later than that I took in different places of New York, singers like Lillie Lehmann, and others.[24] It's uncertain what Wangemann did for a living during this period, but in the latter part of the 1890s, he collaborated with Dr. Frank E. Miller on a series of physiological studies of the singing voice, leading to some minor publications.[25] The 1900 census lists him as an "engineer" living in Manhattan,[26] and a photograph from December 1901 reveals that he was then working in Lee De Forest's wireless shop.[27] Then, in November 1902, Wangemann returned once more to phonograph work in Edison's laboratory.[28] For the next few years, he belonged to a select committee that met twice a month to pass final judgment on records before their release.[29] He also resumed his experimental program in Room 13, characterizing the state of the art as follows in an interview of 1905: "We know nothing definite about sound," he said. "It evades reason, at times, and tumbles upon us frequently by accident, but it is still one of the secrets of nature. We are experimenting constantly to get perfect tone. There is nothing now, however, that we cannot record. We had trouble at first with soprano voices, and later with violin and 'cello solos. We only put 'cello solos on the market about four months ago."[30] That same year, he filed two patent applications building on his acoustic theories, one for a phonograph horn, the other for a horn insert he called a "tone purifier."[31] His interests and skills seem to have been wide-ranging. One source identifies him as "a graduate of the university, a linguist....a painter of note, and altogether a gentleman of rare and varied accomplishments," adding: "He was a composer of merit, but would never permit any of his music to be published, though his laboratory headquarters are littered with his compositions."[32] Socially, Wangemann was a member of the Pleiades Club in Greenwich Village, where it was said in 1904 that he "always opens the first entertainment of the season with the 'Tannhäuser' march at the piano."[33] He also served as secretary of the Muckers of the Edison Laboratory, during which time the editors of the Edison Papers note that "the minutes contain numerous jokes and sketches, along with comical reports of periodic 'outings' by the club, usually to dining and drinking establishments in New York City."[34] Wangemann's death in 1906 was unexpected and tragic. As the Music Trade Review reported: He had been visiting friends in Bath Beach (Brooklyn), N. Y., and started for home in Orange, N. J., at midnight, when, in boarding a car, he made a misstep and fell, the train starting up and dragging him for half a block, his body being badly mangled. Mr. Wangemann never recovered consciousness and died within an hour.[35] According to the New York Times, Wangemann had experienced a premonition of death over dinner that night and expressed his desire to be cremated: "When asked if he expected to die soon, he replied that 'one never knew.'"[36] This article was published on January 30, 2012.

[1] National Phonograph Company vs. American Graphophone Company, Transcript of Record, 59-60. On another occasion he described his duties as "Experimenting and recording of the human voice and music on the phonograph." American Graphophone Company vs. National Phonograph Company, printed record (TAEM 116:541ff), 188. [2] "Death of A. Theo. E. Wangemann," Music Trade Review 42:23 (June 9, 1906): 39. [3] "Death of A. T. E. Wangemann," Edison Phonograph Monthly 4:5 (July 1906), 6. [4] "Edison's Perfected Phonograph," from New York Sun, in Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago), 25 May 1888, p. 3. [5] For a description of another case, see American Graphophone Company vs. National Phonograph Company, printed record, 189-90. [6] "Edison's Talking Machine," New York Herald, May 12, 1888 (TAEM 146:245). [7] National Phonograph Company vs. American Graphophone Company, Transcript of Record, 61. [8] "Speech and Song Embalmed," Fireside News, July 13, 1888 (TAEM 146:276). [9] Will Lomas to Tate, August 9, 1889 (TAEM 127:458). [10] "Kisses By Phonograph," New York Times, Dec. 3, 1888, p. 8. [11] F. Z. Maguire to Tate, January 18, 1889 (TAEM 127:356). [12] "Reported by Phonograph," New York Morning Sun, October 30, 1888, (TAEM 146:248). [13] New York Evening World, December 20, 1888, op. cit. [14] American Graphophone Company vs. National Phonograph Company, printed record, 195-96 [15] American Graphophone Company vs. National Phonograph Company, printed record, 193, 209, 212-13; "The Newest Phonograph," Boston Post, April 20, 1889 (TAEM 146:387); "The Edison Phonograph," Boston Journal, 20 April 1889, p. [6]. [16] First Book of Phonograph Records; North American Phonograph Company, "Price List of Phonograph Supplies for Phonograph f. o. b. Edison Phonograph Works, Orange, N. J." May 28, 1889 (TAEM 128:7). [17] American Graphophone Company vs. National Phonograph Company, printed record, 191. [18] Handwritten copy, Edison to Edison Phonograph Works, January 25, 1890 (TAEM 140:343-46). Typewritten copy of same at TAEM 141:828ff. Other portions of the same letter are quoted by Raymond R. Wile, "Duplicates of the Nineties and The National Phonograph Company's Bloc Numbered Series," ARSC Journal 32:2 (Fall 2001) 176. The date on the badly smudged typewritten copy has hitherto been misread as January 23 but is clearly legible in the handwritten version. [19] National Phonograph Company vs. American Graphophone Company, Transcript of Record, 59. [20] American Graphophone Company vs. National Phonograph Company, printed record, 198-199. [21] Tate to Insull, November 20, 1890 (TAEM 141:741); November 21, 1890, Insull to Tate, November 21, 1890 (TAEM 128:917); Tate to Edison, November 24, 1890 (TAEM 141:750). Wangemann later testified: "in December 1890 and 1891, I was working for the Edison Company in New York." American Graphophone Company vs. National Phonograph Company, printed record, 190. [22] National Phonograph Company vs. American Graphophone Company, Transcript of Record, 59. [23] Tate to Edison, January 9, 1893 (TAEM 134:14-15). [24] American Graphophone Company vs. National Phonograph Company, printed record, 206. [25] Some of their writings are included in Anna Lankow, The Science of the Art of Singing, 3rd ed. (New York: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1903). See also "Marvellous Mechanism Reproducing the Timbre of the Human Voice May Revolutionize Art of Singing," New York World, 21 October 1900, p. 5. [26] Entry for "A. E. Wangemann," 1900 census, Manhattan, New York. [27] Photograph of Wangemann in Lee DeForest's wireless shop, Jersey City, NJ, December 1901. EDIS-Photox.mdb number 10.152/004, NPS-ICMS catalog number EDIS 1730. [28] National Phonograph Company vs. American Graphophone Company, Transcript of Record, 60. [29] "Death of A. T. E. Wangemann," Edison Phonograph Monthly 4:5 (July 1906), 6. [30] "A Study of Edison the Man," Albany (New York) Evening Journal, October 11, 1905, p. 7. [31] Adelbert Theo. Edward Wangemann, "Phonograph-Horn," U. S. Patent 913,930, filed August 3, 1905, issued March 2, 1909; "Tone Purifier," U. S. Patent 872,592, filed September 9, 1905, issued December 3, 1907. [32] "Death of A. Theo. E. Wangemann," Music Trade Review 42:23 (June 9, 1906): 39. [33] "A Bit of 'Bohemia' in the Pleiades Club," New York Times, Dec. 11, 1904, magazine, p. 8. [34] http://edison.rutgers.edu/NamesSearch/glocpage.php3?gloc=ML001& [35] "Death of A. Theo. E. Wangemann," Music Trade Review 42:23 (June 9, 1906): 39. [36] "Had Death Presentiment," New York Times, June 4, 1906, p. 2. |

Last updated: February 26, 2015