NPS photo by Brett Seymour Sea turtles are often sighted around Dry Tortugas National Park. Originally named Las Tortugas (Spanish for The Turtles) by Ponce de Leon in 1513, this collection of small sand and coral islands is famous for the abundance of sea turtles that annually nest in the area. Five species of sea turtle are found in the waters of south Florida: loggerhead (Caretta caretta), green turtle (Chelonia mydas), leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), Kemp's ridley (Lepidochelys kempi), and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata).

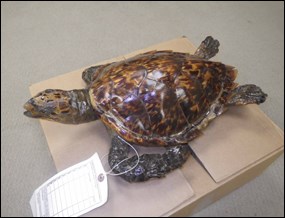

NPS photo All five of these species were once more abundant; however, all five species are now listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Loggerhead, green, and hawksbill turtles can sometimes be spotted lounging on the surface of the sea on the trip between Key West and Dry Tortugas National Park. The name Las Tortugas was changed to Dry Tortugas on nautical charts used for navigation to indicate to mariners that no fresh water was available on the islands. The name change had nothing to do with how wet, dry, or thirsty the local sea turtles were. Please Remember that it is Illegal to Disturb Section 9 of the Endangered Species Act makes it "illegal to take (includes harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect; or to attempt any of these), ... any endangered fish or wildlife species..." The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission interprets the disorientation of sea turtles due to artificial lighting as a violation of the Act. In addition, many dive outfitters even consider harassment to include a diver causing a turtle to alter its course when swimming. Please contact a park ranger to report a person disturbing a sea turtle nest or an injured, dead, or harassed sea turtle. Monitoring Sea Turtle Nesting Activity

Julie Marcero, NPS volunteer Dry Tortugas National Park is the most active turtle nesting site in the Florida Keys. Park biologists have been monitoring sea turtle nesting activity within park boundaries since 1980. Five of the park's seven islands (East, Loggerhead, Bush, Garden, and occasionally Middle key) are surveyed throughout the nesting season to document the presence of turtles. The masked booby colony on Hospital Key precludes monitoring on that island. And, unlike the other islands, Long Key is made of coral rubble, not sand, and therefore is not monitored because historically it has had less than 1% of nesting activity in the park.

Photo courtesy of Kristen Hart, USGS Tracks and other signs left on a beach by a sea turtle emerging from the sea are called a crawl. If the conditions are not right for nesting and a female sea turtle abandons her nesting attempt, the resulting tracks are called a false crawl. If the conditions are right, however, the female turtle will use her rear flippers to excavate a nest into which she will deposit her clutch of eggs. After depositing her eggs, the female will use her front flippers to cover the egg chamber with sand before lumbering back to the water, leaving her eggs to incubate and hatch on their own.

NPS photo Biologists find sea turtle nests by looking for a characteristically shaped mound of sand on the beach. Each nest is marked and recorded and then checked for signs of hatchlings beginning about 45 days later. Although incubation takes about 60 days, the temperature of the sand determines the speed of embryo development, so the hatching period can cover a broad period of time. The speed of embryo development increases with increasing nest temperature. Cooler nests generally produce more males, and warmer nests generally produce more females.

Photo courtesy of Kristen Hart, USGS Sea turtle eggs are about the size and shape of a ping pong ball. After the eggs have hatched, biologists excavate the nest and record the number of hatched and unhatched eggs, live and dead turtles, and any observations such as signs of predation on the nest or indications of arrested development. The requested video is no longer available.

The requested video is no longer available.

Threats to Sea Turtles

NPS photo by Kayla Nimmo Although many thousands of hatchling sea turtles emerge from their nests along coastal areas of the southeastern United States and enter the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of America each year, only an estimated one in 1,000 to 10,000 will survive to adulthood. Natural threats to both young and adult sea turtles alike are abundant, but it is the increasing human threats that are driving sea turtles to extinction. Today, all sea turtles found in United States waters are federally listed as endangered except for the loggerhead, which is listed as threatened.

Photo courtesy of Molly Martin, USFWS Natural Threats Sea turtles living in the waters of Dry Tortugas National Park face a wide variety of natural challenges to their survival. Hatchlings may have to crawl up and down steep, sandy slopes and may become trapped in pits of loose sand along the way. They may encounter storm-eroded cliffs and embankments or mounds of seaweed, driftwood, and other obstacles blocking their way. They may also have to navigate dense tangles of beach vegetation that leave them trapped within, or simply too exhausted to continue.

Photo courtesy USFWS Human Threats Human threats to sea turtle survival are many and varied. Not all countries offer protection to sea turtles and eggs, and of those that do, enforcement may be lax. Humans harvest turtle eggs and meat for consumption and may harvest other turtle parts such as oil, cartilage, skin, and shell to make products. Naivety and a general lack of information about sea turtles leads many world travelers to unwittingly support the illegal international black market for sea turtle shells and products. Buying, selling, or importing any sea turtle products in the United States, as in many countries around the world, is strictly prohibited by law. Adult and immature sea turtles often are accidentally captured in commercial and recreational fisheries in fishing and shrimping nets and lines and may be injured or killed by vessel strikes. Death by ingestion of discarded plastics and entanglement in marine debris, such as lost or discarded fishing gear, also is a major threat to sea turtles. Sea turtles that are lucky enough to hatch and live in protected areas such as national parks are protected from some but not all human threats, and they also frequently cross park boundaries and travel into unprotected waters.

NPS photo by Kayla Nimmo Urbanization and coastal development in the form of sea wall, revetment, and jetty construction cause destruction and alteration of nesting and foraging habitat, as do beach nourishment and dredging projects. Near-shore artificial lighting discourages females from nesting in ideal spots and disorients hatchlings, leading them to wander inland where they may die of dehydration, exhaustion, or predation, or be crushed by vehicles on coastal roadways. Recreational beach use during both day and night can crush eggs and hatchlings and deter females from nesting. Invasive species and feral and even domesticated dogs and cats may devour eggs and hatchlings, and have been known to attack nesting females. Oil and chemical spills and runoff from fertilizers cause marine pollution that contaminates food sources, resulting in disease. Rising sea levels that result from climate change decreases the size of nesting beaches, and warmer temperatures during incubation could affect the sex ratio of the hatchlings.

Photo courtesy of Kristen Hart, USGS Although the large number of human threats to sea turtles can seem overwhelming, greater public awareness and support is an important first step toward sea turtle conservation. In addition, ongoing research projects enhance scientific understanding of the biology, requirements, and habitats of sea turtles and inform wise conservation and management decisions. Learn about a current sea turtle research project in Dry Tortugas National Park and more about green sea turtles and leatherback sea turtles. |

Last updated: February 24, 2025