Marianne BoruchMarianne Boruch, of West Lafayette, IN, is a poet whose eight collections include the recent Cadaver, Speak and The Book of Hours (Copper Canyon Press, 2014, 2011). She's also written two essay collections about poetry, and a memoir, The Glimpse Traveler (Indiana, 2011). Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, London Review of Books, American Poetry Review, and elsewhere. She's been awarded fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation, and artist residencies at the Rockefeller Foundation's Bellagio Center (Italy) and at Isle Royale National Park. Boruch was a Fulbright/Visiting Professor in 2012 in Edinburgh, Scotland though usually she teaches in Purdue University's MFA program which she established in 1987. Much of her work concerns the natural world, especially her Kinsgley-Tufts award winning The Book of Hours, the fierce and mysterious nature of that world and our troubling human place in it.

—for David You Bach yourself or Schubert yourself, light outside in the cabin dark, 11 pm, Denali

at treeline, the grizzlies still awake finding berry unto berry, getting larger

for their trouble, enough to doze all winter. But it’s August! And you

Mozart yourself, our bed a concert hall of one, that wire in your ear to

in time out of time as the moon—is there really a moon this semi-night?—bestows itself

over mountain and tundra. Bestows! Old word

growing older that finds us later and late, dear listener

of worlds above river stream and gravel bar, caribou to hare to crow,

the dot and dash of sheep up there, some arctic squirrel curious, a miniature

time stop, little sentry of the Park Road reeling up, back--wind

and scent and wolf. This dream to keep hearing, hour unto hour

sleep, our simple shared ageless, about to. — Denali National Park, Alaska, August 2015

around cloud. You open, you reinvent the scheme of room and table. This cup of tea equals--- Patience is a word with a window in it.

chanted yesterday to be funny, opening his arms wide at the turn-off near Stony Hill. Which is how we strangers to each and all stood longer in the vast cliff brown green blue-- no joke, no words for it. * * * Fireweed chronically alert outside cabin #29 above the Toklat river. Before names, before McKinley or Denali, either-or this fireweed so sure of itself, wily post-us, pre we-named-this-plant because I’m loyal. No matter. Fire or ice, I come up however earth is scorched. To believe in one many-paned window is to love the obvious involved: cloud and sky all upper glass looming how far far is. Of earth and close, the lower half mobbed by that fireweed. Tiny flames, high stems. Pull back and in. The cabin’s rusted can of pencils on the sill, erasers worn down by second thoughts. Someone here first. No, everyone here first! A candle, an old book about wolves bears, sheep, lynx-- The nerve: do I think I’m actually doing something? Between our little and the large? Vague ringing in the ear these mornings makes a kind of silence. Late summer. Spruce letting in blue through its spikes. To be here, to stall speechless at what mountains do and keep doing--is it the human part that sees or the cheap auto-brief-buzz camera part? Simple words again: tree, gravel bar. Look up-- amazing! Yeah. Like a caption is needed. What I really want? Not the physics of eye and brain taking in light to make color, not behaved in some frame. A hunger so old and split-second lunge, so time-rich, time-starved, wooly musk-matted... The grizzly rears back, massive head going left then right. So the Ranger mimes to warn big, a cartoon of bear bent over us, closer, his scent-roar Moose? Caribou? What is that-- Worse. My face and my fear, my two arms in a down vest. * * * The higher the flowering on fireweed, the sooner winter shows up. This plant tells time! Three people said that. I do see a quickening. Every few days another hour of light shot, the flower shedding beauty and adding beauty, low shutter speed up the stem. The heart sinks into its permafrost. * * * Okay. A common enough story-- Day six. Two bears stop our hike until a safer place down the Park Road to enter and go up past lichen and moss, past the spare yellow work of flowers. Climb and climb, off-balance scary particulars, narrow ledge and stones, my boots and sticks where caribou leave closed parentheses in mud, the spot one of them tracked, stood and straight up turned: sudden Denali in snowy splendor. Nothing ironic, this too big a dream. Rain at night urgents into day. Drops of clear vision on fireweed, tip of spruce and willow, on the rope’s knot out there-- Window for a reason, inside where I write human enough, in two shirts, a wool sweater. * * * Always a map of this world, and emphatic somethings on a sign. It’s the raven sleek-ragged flapping there, folding down to scold at the Toklat Station, his cranky eloquent you, how dare you, yes you and you…. We’re just so beside the point, right? Only is is is to walk and to breathe. The boots I think waterproof aren’t. But we hike the tundra anyway, soggy each next and next gives way to the underworld, tangled low willow, what a god-forsaken maze to get through. All of it farther, the Ranger saying see that ridge? (stanza break) Miles, and rain turns snow. Wet into old isn’t long. Berries. Roots. Twigs. The bear beyond us or so like us, making ready for that dank underground, crazy now, raking everything into his mouth. Later, what in me keeps waking? Same rain the small hours--let go, let go-- off overhang and roof. Expand. I mean stop. You step in tundra and it might recall something. The brain takes the imprint danger, the drastics the way snow remembers night’s freeze on the mountain even at noon. First news I heard at Denali: a photographer snapping and snapping too close. Proof: his flannel shirt in that bear, indigestible woven blue and black bolus. And they did with it—what? In a jar? On a shelf? Some dusty afternoon? The things that keep me awake. * * * Fireweed, your blossoms are red paper shards of blossom. I count six, seven—would that be weeks until winter? A clock ticking, here where there is no clock. Early to ancient undoing year whatever this is. A branch. In wind. Dark as rain can ink it—

NPS Photo / Kent Miller Sonja HinrichsenSonja Hinrichsen, of Oakland, CA, engages communities worldwide with an ongoing, participatory community arts project, "Snow Drawings." She graduated from the Academy of Art in Stuttgart, Germany and received a masters degree in New Genres from the San Francisco Art Institute in 2001. She has won numerous artist residencies, including the Bemis Center in Omaha, Djerassi in California, the Santa Fe Art Institute, Ucross Foundation in Wyoming, Valparaiso in Spain, Fiskars in Finland, and Taipei Artist Village in Taiwan. Her exhibitions include the DePaul Museum in Chicago, Kala Art Institute in Berkeley, Chandra Cerrito Contemporary in Oakland, San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery, Saarlaendisches Kuenstlerhaus in Germany, Organhaus in Chongqing, China.

John KooistraJohn Kooistra is a poet and essayist who has lived in Alaska since 1973 and Fairbanks since 1981. He has taught philosophy at the University of Alaska, Purdue University, the College of Wooster. He fished commercially in Cook Inlet for thirty years, and worked at various times as a tradesman. He's traveled a lot by thumb, car, motorcycle and bicycle over the past 50 years, activities that have resulted in a lot of travel and journal writing. His poems are grounded in the world, in season and place and go on from there to consider the timeless human nature we share. A book of travel recollections and ruminations is presently ready for publication.

A cow moose comes She’s HUGE the same as I would This is a long moose I think When the lights that aren’t there but I’m clumsy Yelizaveta P. RenfroYelizaveta P. Renfro, of West Hartford, CT, is the author of a collection of essays, Xylotheque, available from the University of New Mexico Press, and a collection of short stories, A Catalogue of Everything in the World, winner of the St. Lawrence Book Award. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Glimmer Train Stories, North American Review, Colorado Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, South Dakota Review, Witness, Reader's Digest, Blue Mesa Review, Parcel, Adanna, Fourth River, Bayou Magazine, Untamed Ink, So to Speak, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA in creative writing from George Mason University and a Ph.D. in English from the University of Nebraska. Currently a resident of Connecticut, she's also lived in California, Virginia, and Nebraska. Visit Yelizaveta Renfro's website. "What do you do as the writer-in-residence?" During my stay in Denali last July, I got this question a lot. Of course, the short answer is: write. But it isn't that simple. I didn't come to Denali and lock myself away in a cabin for ten days. The "writing" that I did was more a process of experiencing a place and taking a lot of notes. Much of the actual writing takes place later, after geographic and temporal distance gives me the space I need for reflection. While I was in Denali, I was simply there. I came to Denali with a notebook and some pens and a camera—no computer, no smartphone, no screen of any kind. Back home in Connecticut, I spend more time looking at a screen than I do looking at landscape, much to my detriment, so here I wanted to do the opposite. After ten days, I had many pages of hand-written notes and drawings and sketches, hundreds of photos on my camera. I hiked across the tundra and across gravel bars and stood on ridges and walked the park road. I saw the mountain, and then I didn't see the mountain for many days. I gorged on blueberries, tried crowberries, and even sampled a soapberry (which I don't recommend). I went out in sunny weather and in rain and in fog. I found caribou fur and antlers and bear digs. I saw a rainbow over Divide Mountain, and I saw a herd of about seventy caribou streaking across the hillside. I saw Dall sheep, moose, golden eagles, Arctic ground squirrels, marmots, snowshoe hares, a porcupine, magpies, ptarmigans, and bears. A lot of bears. Every day for nine days straight, I saw bears—most of them from the bus or car windows. When you see more bears than mosquitoes—that's a good trip to Alaska. I watched a bear and a caribou walk right past each other. I saw a bear digging for ground squirrels and another napping in the sun. I watched a bear bounding down a hill at top speed, and I saw a blonde mother bear with her two chocolate-colored cubs eating berries right by the road. I learned about a lot of plants and trees: spruce, willow, birch, fireweed, gentian, cinquefoil, arnica, monkshood, azalea, harebell, tundra bones, grass of Parnassus, and Eskimo potato. And even if you think you know what an azalea is, the diminutive tundra version will amaze you. I lived alone in a cabin at Toklat, at Mile 53, which allowed me to experience being in the park late at night after the buses have stopped running and all the day visitors have left. Late at night I walked out on the bridge over the Toklat River and looked at the glow on the mountains and listened to the profound silence. Being right there at Toklat, I also had the opportunity to experience life at road camp—a behind-the-scenes look at what goes on in running a national park. I learned that rangers are so much more than stern enforcers of the law and protectors of the wilderness who get to wear cool hats. On a Discovery Hike with Ranger Greg I learned about the wolves of Denali. I talked about the tundra with Ranger Tina on another hike. I talked about the concept of wilderness with Ranger Jonathan, who is working on his Ph.D. in history when he isn't busy being a park ranger. I found wolf and caribou tracks in the East Fork River with Ranger Emily. Hiking on a hillside with Ranger Ali, we talked of another place we both know and love—the Mojave Desert of California. And I am very grateful to Ranger Bob, who escorted me around bears on more than one occasion. I also learned an extraordinary amount from the many bus drivers—Mike, Mona, Wayne, Anna, Paul, Beth, Lindy, Erland, Frank, and Elton —I had along the way, riding the camper bus and the discovery bus and the regular green buses all over the park. Everyone I met shared their knowledge and love for this place with passion and enthusiasm. Everyone I met loved to work at Denali—that's why they were there. How many places do you encounter in your everyday lives where everyone loves the place they are in and the work they are doing? Not many, I would guess. I also watched park visitors interact with Denali in a whole range of ways. I met people from Tennessee, Michigan, Ohio, California, Minnesota, Connecticut, Texas, Washington, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Colorado, Florida, Nebraska, Wyoming, as well as many international visitors from places like Japan, Brazil, Belgium, Germany, Poland, Hong Kong, France, and Bermuda. One of my roles, as writer-in-residence, is to help interpret the park experience for others. The way the writing process works for me—and for many writers—is that there's a fairly lengthy rumination period that occurs after an experience. While I'm in the middle of it, I'm still forming impressions, still figuring out the shapes of the nascent narratives that are emerging. My story is still finding its way, seeking a path like the water in the braided rivers. Some of the impressions, though, glint like the threads of those braids in sunlight. When I was riding Mona's camper bus from the park entrance with a group of adventurous campers who were going out to Wonder Lake, she said to them, "Most people who come to the park only look at the landscape. You're going to be part of the landscape." This is an idea to consider. The landscape is not just something to look at and photograph from a bus window or visitor center parking lot. The landscape is something to experience. Don't merely take photos with the landscape behind you as a backdrop to show your friends back home that you were here. Take a few pictures, sure, but then put your cameras and screens away. How can what you are seeing compare to anything on your screen? And how can you ever capture it adequately in an electronic device? Experience it unmediated. Capture it with your mind—that is the only device capable of holding it, of truly taking it in. So walk into the landscape. Become a part of it. Strike out across the tundra—even if you just go a short distance. Experience the two-dimensional backdrop of landscape becoming three-dimensional space as you enter it. On a Discovery Hike with Ranger Ali, we climbed high up on a hillside with the road below us. A bus traveling on the road stopped, and all the binoculars on the bus were trained on us. Someone had seen movement, and they were all checking us out. "We are the wildlife," Ranger Ali joked. And in a way, it was true—we had become the creatures who move and live in this space. I hiked the alpine trail up above the Eielson Visitor Center on a cold, rainy, foggy day. I accompanied Ranger Jonathan, a group of three from Belgium, and a couple from Connecticut. When we got to the top of the ridge, we couldn't see anything—just fog, all around. The visitor center down below was completely obliterated in white. Still, we took pictures on the summit with just that white as a backdrop. And then Ranger Jonathan said, "We all share something very important in common. You could have gone on vacation anywhere in the world. You could have gone someplace warm;you could have gone to Disneyland. But you all chose to come here, to Alaska, to Denali." And that is what all of us in this park share in common as well. We all picked this place, for whatever reason. This is not a place you're likely to end up by accident. It takes a lot of planning, a lot of effort to come to Alaska. And we all share that desire to be here. In his documentary series on the national parks, Ken Burns explores the notion that the National Park System is America's best idea. Denali exemplifies this. Just look around you. Protecting all of this? I can't think of any better idea. Saving this place—and the hundreds of others in the National Park System—is something we got right. And the fact that people from all over the world come here—the fact that all of you are here right now—is a testament to the wonder of this place and our protection of it. On one of the Discovery Hikes I went on, Ranger Tina asked the hikers how they would describe walking on the tundra to someone who has never done it. The answers varied. Walking on tundra was compared to walking on marshmallows, on sponges, on foam, on snow, on velvet, on a Tempur-Pedic mattress, on a waterbed, on carpeted bowling balls, or walking like a drunk person. "It is indescribable," one visitor said, and that is the truth. To say that it's like anything is to diminish the experience. The reason we do these things—the reason we visit national parks and watch caribou and walk on tundra—is because these things are unlike anything we know. The fact that I cannot describe it—that words fail me—is all the more reason for you to walk on the tundra yourself. It is an experience unlike any other, an experience I cannot interpret for you. A couple of days before my departure, I met a man named Lee who was originally from Texas but now lives in California. He worked for forty years at a desk, and then at the age of sixty he started hiking. He's now in his seventies. He told me that the wilderness affects him so profoundly that sometimes he just sits down on a rock and cries. That is how a place like Denali can affect us, if only we open our eyes and our minds and our hearts to the wilderness.

David RosenthalDenali and Wonder Lake and Denali on a Blue Day Denali is a wonderful subject for a landscape painter. Towering above its surroundings, Denali catches the ever-changing northern light. The beautiful, pristine environment with many available viewpoints creates an endless number of scenes worth painting. During my time as an artist in the park, I filled a sketchbook with drawings. Using these drawings, memory and experience I painted these two small oil studies, along with about twenty other studies, back in my studio.

— David Rosenthal, 2015

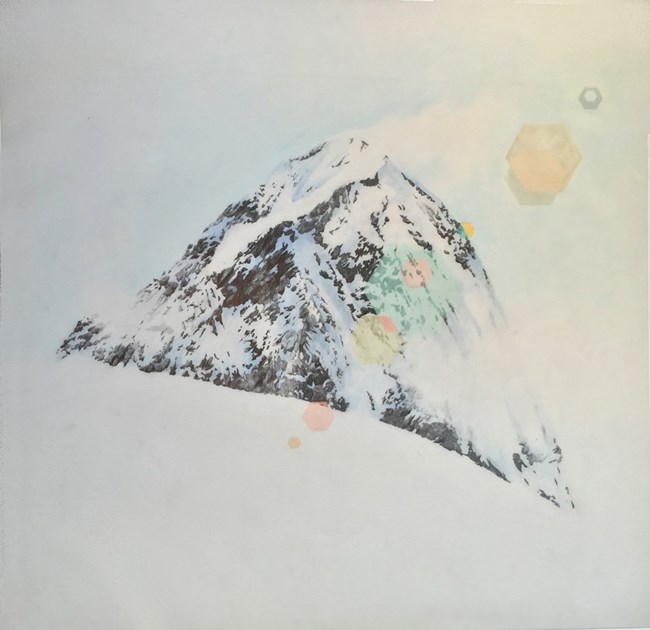

Brooks Salzwedel Brooks SalzwedelOne That Was Once Unnamed There are very few experiences that change a person's outlook on life. For myself, spending time at a secluded cabin in the middle of Denali was one of those times. As I ventured to the end of the Park Road one evening, I saw Denali unshrouded by clouds. It was breathtaking. I felt eclipsed by this monumental body as though I was a tiny insignificant ant, yet at the same time I felt the importance of life, and my own. During my residency, the name of the mountain was changed from Mount McKinley to Denali. It was hard not to be affected by the talk surrounding the subject. With Unnamed #1, I wanted to show the importance of the mountain, its greatness and simplicity, which is why I depicted the lone peak assorted with the color of a lens flare. The mountain, as well as the light of Alaska, should not be disregarded. When the sun does lower, it doesn't fall to the bottom of your eyesight but curves to the side. The sights I saw, the feelings I felt, along with all other senses of the park, will never be forgotten. — Brooks Salzwedel, 2015 Brooks Salzwedel, of Los Angeles, CA, earned a BFA Cum Laude from Art Center College of Design in 2004. His work has been displayed at the Hammer Museum, and acquired by The Houston Museum of Contemporary Art and the Portland Art Museum. His landscapes reflect the subtle friction between urban development and nature. Evoking the fragility of our environments, his medium of choice is graphite, a natural mineral, resin, a byproduct of plant materials, and mylar, a manufactured film, through which he accomplishes ethereal artworks with a sense of depth. Some of these pieces are cast in vintage medicine tins and corroded pipe-ends, lending an intimate quality to the works. Visit Brooks Salzwedel's website.

Camille SeamanI welcomed the silence of winter and the break from gadgets and technology. My time in Denali rewarded me with peaceful solitude, happy dogs and amazing vistas. The images I made during my residency are just the start of what I know will be a life long love affair with the park.

— Camille Seaman, 2014 Camille Seaman, of Emeryville, CA, strongly believes in capturing photographs that articulate that humans are not separate from nature. A TED Talks Senior Fellow and Stanford Knight Fellow, her photographs have been featured in National Geographic and TIME magazines. She has a bachelor's degree in the fine arts photography from the State University of New York at Purchase. She has won several photography awards, including a National Geographic Award and the Critical Mass Top Monograph Award. In 2008, Seaman was honored with a solo exhibit, "The Last Iceberg," at the National Academy of Sciences. Seaman advocates the importance of recognizing the relationship between humans and their natural surroundings.

|

Last updated: March 7, 2019