Harlan ButtDenali Jar I Haiku:

The imagery on the jar is of the mountain range south of East Fork Cabin and the silvery pattern of lines running vertically in cloisonné suggest the braided character of the rivers in Denali. On the top of the jar is a landscape of the earth at our feet, including simulations of nagoonberry and poplar leaves. The haiku, which circles the rim, describes an experience one morning outside the cabin. The contemporary dialogue focusing on the environment and the global impact of human habitation on its health and diversity involves serious debate on several key issues. Conservation versus preservation of wilderness, capitalism as a sustainable system of economics on a planet of limited natural resources, anthropocentrism as a world view, as opposed to biocentrism, and accusations of environmentalism as a new form of Western imperialism. It is no longer as simple as appreciating the beauty of a willow or the majesty of a caribou. — Harlan W. Butt, 2011 Harlan W. Butt is a metalsmith from Denton, Texas. Harlan's unique enamel and silver vessels are inspired by a love of nature and poetry. He is a Regents Professor of Art at the University of North Texas where he has taught since 1976. He is past President of the Enamelist Society and a Fellow of the American Crafts Council. His work has been exhibited in Australia, Canada, England, Germany, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and throughout the United States. He has spent time studying in Japan, including a year working in the studio of master metalsmith Shumei Tanaka and at the Biso Cloisonne Company, both in Kyoto. Visit Harlan Butt's wbsite.

Richard FruthIt's Beautiful and Yet Dangerous in the Wide Open Spaces I knew I was in a strange and unpredictable place with an endless plot. The densely packed forest areas are visually stunning but the amount of population before my eyes is confusing. Sometimes, the vast overlapping trees create a visual vibration that gives the illusion the caribou that once were in the foreground has vanished behind the pine curtain. The wide opened space is far more interesting. The capability to see any animal in the distance is phenomenal. They are a dot on the landscape, so minuscule. Blending in with the hills and tundra and at the same time but being a separate part from the surroundings. While hiking on the main road that follows along the East Fork River leading into the Poly Chrome Glaciers, I saw a caribou struggling in a kettle pond. The experience was overwhelming with joy and then unexpectedly filled with sadness as I witnessed the caribou exhausting all of his strength to remove himself from the pond. Further in the distance a lone wolf was watching the struggling caribou and perhaps myself. Cautiously the wolf traveled towards the caribou, stopping occasionally to check his bearings and if there was additional activity in the area. The suspense was gut wrenching and as much as I wanted to help the caribou, I knew I could not become an active participant. Realizing, the unraveling outcome is no different than a traffic accident that occurs in the city. This is the average rush hour day in Denali and the passing conversations between the animals may be friendly or brutal. — Richard Fruth, 2010 Richard Fruth is a sculptor from Cincinnati, Ohio. Richard's sculptures have a whimsical, humor-based aesthetic and are often made out of wood, bronze and paint. Richard received a Bachelors of Fine Arts degree in Photography in 1994 and a Master of Arts in Studio Arts in 1998 at Ball State University, Muncie, IN. Thereafter, he pursued a Master of Fine Arts degree in sculpture in 2001 at University of Cincinnati. His artwork focuses on two points of interest; the narrative, such as telling stories relating of the past, future, biological or psychological. His second point of interest, focuses on the use or abuse of the English language, specifically how language becomes repetitive, negative and sometimes humorous. He is represented by Sandra Small Gallery in Covington, KY.

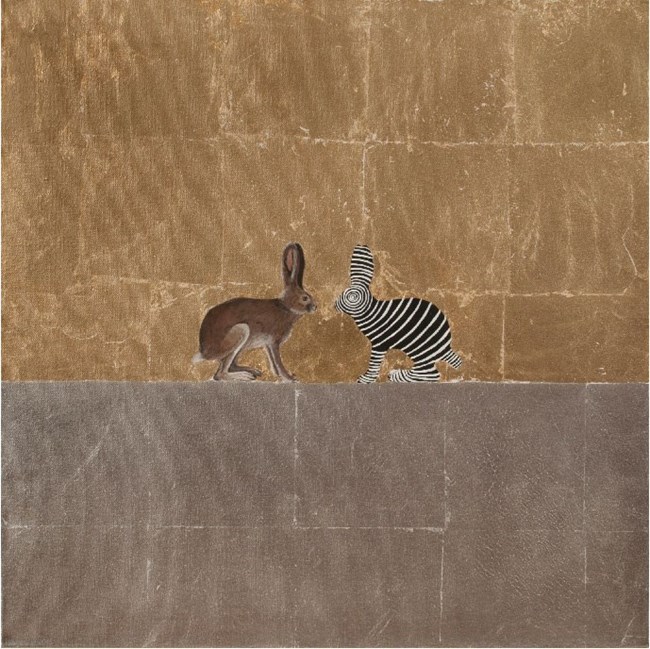

Kristen FurlongAlaska Gold: Snowshoe Hare My current artistic practice involves engaging with a series of questions about the geography of human/animal interactions as a way of contemplating various issues about the natural world. The time I spent at Denali National Park and Preserve as an artist in residence was an amazing environment for experiencing and observing my own and others attitudes and feelings about animals in the park (wilderness) versus those found in their everyday setting (urban, suburban). The images I create are influenced by representation of animals found in such diverse sources as historical scientific illustration to current popular culture. In the paintings and prints, animals serve as representations of nature and as metaphors for human desires that ultimately separate us from the natural world. While in Denali, I had the experience of being overwhelmed and in awe of the sheer scale of the landscape and of the large animals, such as bears and wolves, that I encountered. This led me to concentrate on creatures and plants of more diminutive size — such as the snowshoe hares, arctic ground squirrels, and many cryptogams (fungi, lichen, moss) that were abundant near the East Fork Cabin. The painting I created for the Denali collection places the snowshoe hare in iconic status on a silver and gold background to signify its importance in the ecology of the area and to allude to historical and contemporary human interests in the natural resources in the lands of Alaska. — Kristen Furlong, 2010 Kirsten Furlong is a mixed media artist often working in drawings, paintings, prints, and installations. Her work documents her experience of the intersection of nature and the ideologies that frame our cultural understanding of the natural world. She examines the relationships people have with wild and domestic animals and see her art as a diagram of these narratives. Kirsten is currently the gallery director of the Visual Arts Center at Boise State University. She is also an art department faculty member at Boise State teaching a variety of studio arts. Grants from the Idaho Commission on the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Boise Weekly helped to fund the residency and the work that followed. Visit Kristen Furlong's website. Nancy LordTen Denali Days: Poems From a Residency What a gift, to have ten days at the East Fork Cabin and to be able to explore the park at will. I most appreciated having access to other people (scientists, rangers, wildlife technicians) working in the park, from whom I could learn. In the evenings, I read through the library of Denali-related books and made copious notes. My writing background is in prose, and I completed both an essay and a short story based on my experiences. The quiet time and sparks of aware ness also seemed to support a poetic approach, and so I wrote some of the first poems of my life. The experience, overall, was a creative opening for me—not just to a fresh and dramatic natural world but to new ways of seeing and thinking. — Nancy Lord, 2010 Previous guests complained

in the cabin logbook of creaking window shutters. They wanted a wild quiet. One hour in, Ken has tied back the shutters against any pummel of wind, fashioned a quick release for each time we leave on a berry pick or hike. Each time we leave the cabin we lock the prickly shutters shielded with nails against those bears that would covet our meatloaf and potatoes. Each time we return we tie them back. The windows open to purple mountains cushioned in clouds, a magpie weighting a willow branch, fat-tailed coyotes, dark. Nights, I lie awake and listen: MMM light rain tapping MMM MMM construction and supply trucks on the road MMM MMM MMM my ticking clock MMM MMM MMM MMM and some small creature gnawing wood in the spaces between Ken’s thunderous snores. She pulls it apart with the tip of her trekking pole Hare pellets all through the brush, The caribou’s is dark and shiny, loose Contrast the moose—nuggets large and shapely The feather-footed ptarmigan that warms in winter Here’s a fresh, giant pile of red soapberries, skins barely The fox’s, familiar as a small dog’s, with twisted, Everywhere, the unlucky hares’ feet. The wolf pup removed from the East Fork den on May 15, 1940, was taken for the purpose of checking on the development of the pups at the den and familiarizing myself with wolf character. — Adolph Murie, The Wolves of Mount McKinley, 1944

Don’t you love the passive tense? (Mistakes were made?) We called her Wags. Adolph Murie, rightly esteemed for his pioneering field research, Murie also kept a pet wolf. May 1940. Fresh snow at the cabin. The bluff, the river view, the tracked and trammeled snow. . . . the soft whimpering of the pups. It seemed I had already intruded too far. . . As I could not make matters much worse . . . Murie wormed his way into the burrow, counted six squirming The other two were returned. Wags was taken to live with Adolph’s family (wife, little girl, baby). Most of the time, she was chained near the cabin door. The Murie family moved on, and Wags was taken You feed me pancakes You, splayed on the hillside and plunking as they drop so much harder to find. Buses tourists with cameras. They Your hands cup that wealth, crushed beneath you. A luscious And then someone yells. bear. You complain to me now He was a nice man who said to you turned away. The sow rolled over That’s the story you tell, Buses on the string of road squeeze past one another, One driver cups his hands into a cone ahead of his nose. Two hands again, in front of teethy face. Thumbs together,

beside the braided river, climb the bluff with fistholds I wander there, amongst bent grass and yellowing leaves, Shall I go on, alone and far from camp on twisty ground? I stand a long time, staring across the distance, And still, they are. Murie learned, and this we know: wolf packs are dynamic. That’s all I want, really, in coming this way: to get close On the cabin porch, in comfy plastic armchair, The resident ground squirrel at my feet Clouds of bus-dust rise over the road. The buses Hikers’ cries float from the Overnight, the willows growing in a line up the ridge On the drive back from

Feather stuck to glass, Yellowed willow leaves Magpie on the wing Three-toed dinosaurs In the presence of extraordinary actuality, consciousness takes the place of imagination. — Wallace Stevens

I said something about the inadequacy of language for speaking of Nature. Sure, it’s an amazing experience to be in Denali National Park. The mountains are majestic, the views are awe-inspiring, the wildlife is—what? Pretty darn great. How do you be a writer in such a place? I can’t use any of those words. I won’t write sacred, magnificent, grand or grandeur. I won’t write of noble beasts with fire in their eyes. The language is trivial. It’s been done. I’ll cut off my hands before I’ll pen holy. No, I don’t deny the truth of what we find and feel in wild places. That’s where clichés come from. They’re so true they get said again and again, until they’re like drool. Please spare me from hearts that soar with eagles. So the man asked the question—or made the suggestion. Why not invent new words to capture all that freshly? The look of the dawn and the smell of the aster, why can’t they be rendered in words that are coined? What words would I make for the view up the valley, the mountain appearing from clouds? I stood on the stage and my mind filled with pictures—that valley, that mountain, the colors of green. The pictures came from neurons and synapses snapping, a part of my brain that lived before language and knows what it loves without having to speak. I stood before people who were grateful in Nature, who didn’t need to debate their expressions of joy, and I was stupid before them. I wasn’t crazy about the height. There we were, one paleontologist who might have been a mountain goat, his two assistants, and me, scrabbling up a mountainside of tilted and crumbling rock strata—or what my companions called “bedding planes.” Loose gravel and rock dislodged by our feet bounced all the way to the glint of streambed in the canyon’s crease below. I tried not to look down as I followed the others in diagonal ascent, and I thanked my new boots and their grippy soles. Straight out, the view was enough to stop me in my tracks—past the steep gray mountainsides to the green, softening-toward-yellow alpine slopes beyond, and then the farther rocky mountains, all fiery yellows and reds under a high overcast. I could so clearly see something I’d just learned—the geological difference between where I was and where I had been that morning, two parts of Denali National Park. When I’d left the park road to hike up Tattler Creek, I’d walked back through time. The colorful Polychrome Mountains are volcanic, from magma-spewing events 40 to 50 million years ago. But the gray rock of the Cantwell Formation in which I now stood was considerably older, formed during the Late Cretaceous period some 70 million years ago from river and lake sediments deposited in a basin. That basin, later, was lifted by tectonic pressures, tilted, and eroded. “Rock!” Another hunk of mountain bounced past me. The mountain goat in our lead, Tony Fiorillo, had zeroed in on a particular ledge and was poking his way along it, examining its underturned face. A paleontologist from Dallas’s Museum of Nature and Science, Fiorillo has worked in Alaska for many years and specializes in high-latitude dinosaur ecosystems. On this trip, he and his two assistants had gotten chased out of their planned study area elsewhere in the park by an aggressive grizzly and so had returned to Tattler Creek to further document what was becoming a major location of dinosaur fossils. “The candy store,” Fiorillo called it. This area—one of several along the Cantwell Formation in the northeast part of the park—“is the paleontological equivalent of a candy store,” he’d told me when I—a writer visiting the park through its artists residency program—joined him along the creek. Fiorillo was the proverbial kid in the candy store, as excited about every rock on every ledge as any four-year-old let loose among jars and packages of sweets. Now, he was kneeling and squinting and feeling, studying what was embossed in ancient mud. It looked, he called to us, like the track of a “baby” theropod, but—more exciting—a track next to it might belong to a pterosaur. After consultation with the other two— Thomas Adams, a doctoral student who does 3-D laser scanning of dinosaur footprints, and Sarah Venator, a National Parks Service technician—Fiorillo set to work mixing compounds to make a resin cast of the two tracks together. I sheltered in a protected area below them, still focused on not looking down. •

The story has entered the realm of legend, so oft-told has it become: In 2005 a geology professor, Paul McCarthy from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, was teaching students field mapping (that is, how to observe, analyze, and record geologic features in the field) in Denali Park. At an outcrop of the Cantwell Formation, he stopped to explain that that kind of Cretaceous sedimentary rock commonly preserves dinosaur tracks and that they should keep an eye out. At that time, dinosaur footprints had been discovered on Alaska’s North Slope and in Aniakchak National Monument on the Alaska Peninsula, far to the south, but nowhere in interior Alaska. McCarthy had no sooner finished his sentence than two of the students pointed to a spot not far from his gesturing hand and asked, “Like this one?” That grizzly-sized track, of a three-toed dinosaur known as a theropod, was later removed from its exposed location along a stream and displayed at the Murie Science and Learning Center near the park’s entrance. At the university, Susi Tomsich, one of the two alert students, is now a Ph.D candidate and co-author of a number of scientific papers related to understanding the environment of the Cantwell Formation when dinosaurs roamed. The geology department prominently features on its webpage a photo of that first dinosaur track with the promotional words “discovered by students.” The unambiguous track looks like a giant bird foot. •

Theropods. I’d never even heard of them before my trip to Denali and was trying not to confuse them with pteropods, or “winged feet,” tiny swimming marine snails I’d been learning about in another context. (Theropod translates to “beast foot” in the Greek.) Now I’d seen several of their tracks in place and had even learned to distinguish them from other tracks we’d been examining. Back down in the main valley, before we’d headed up a side canyon, the energetic Fiorillo—a slim, well-tanned man in faded blue jeans stained on the knees from kneeling among blueberries—showed me my first dinosaur footprint. Amongst jumbles of other rocks and boulders that had fallen, washed, or been ice-shoved into the valley and were surrounded by the last blooms of dwarf fireweed, one was shaped into three large, smooth, unnatural-looking lobes. “They’re all through here,” Fiorillo enthused. “Once we knew what to look for—it just doesn’t stop.” I rested my hand on a sun-warmed rock toe. This was no ordinary fossil, no mere leaf or shell print in rock; a dinosaur had walked here. To hold that rock was not quite like grabbing a dinosaur by the toe, but the sensation was ticklishly related. I was not in a museum or a roped-off tourist attraction, and I was not looking at a photograph; here was the solid, physical manifestation of a very large near-mythic animal that had once—so very long ago—not only lived, but lived here. I expect I knew less about dinosaurs (“terrible lizards”—I knew that much) than the average seven-year-old, but Fiorillo, patient teacher that he was, paused his trek to give me a short course in Alaska Dino Basics. The rock we were looking at was the three-toed track, about a foot long, of a hadrosaur (“bulky lizard”), a duck-billed, sometimes horned, plant- eating dinosaur that grazed in large herds and has been called “the cow of the Cretaceous.” The adult animals (depending on the species) could range from ten to forty feet long. They had powerful hind legs, smaller front legs, and thick tails. They generally walked on all fours. Some seventy million years ago, towards the end of the Cretaceous period but before the cataclysm (generally agreed by scientists to have been a giant asteroid hit near today’s Yucatan Peninsula) that resulted in the extinction of all dinosaurs as well as much other life on our planet, one of those hadrosaurs living in this northern place had stepped in mud or other soft sediments and left a hind footprint behind. That imprint had later filled with sand or other material harder than the mud, and when the mud eroded away, the cast of the print—the rock we were looking at—was left. “The fossil is the infill,” Fiorillo explained. The rock casts were examples, Fiorillo, said, of “trace fossils”— fossilized evidence of animal behavior. “These can help tell us how the animals lived—the tracks as a data set to complement bones found elsewhere. When they’re found with other fossils—like horsetails or tree cones—that tells us more about what kind of environment the dinosaurs lived in.” And what was especially valuable, he said, was that those dinosaurs lived right here—or very close to here—in what is now interior Alaska. While older Alaska rocks originated elsewhere and moved in on blocks pushed by colliding continental plates, the Cantwell Formation rocks formed in place, after mountains eroded into a basin and their sediments accumulated in layers. The mountains we were now in were only pushed up later, elevating and twisting what had been a braided river and lake topography. “These dinosaurs were Alaskan,” Fiorillo said. “They weren’t hijacked tectonically. We have an opportunity to study an ancient polar ecosystem in a warm climate.” That climate, at a “greenhouse” time in Earth’s history, was temperate, perhaps like that of the present-day Pacific Northwest. Winters would have been marked by cold but not frigid temperatures and by snow—as well as by the low light and darkness typical of northern latitudes. The dinosaur tracks get the most attention from the public, but the larger value lay in studying the full ecosystem preserved in the Cantwell Formation. Other trace fossils found among the dinosaur prints include plants (from ferns and horsetails to the cones of Metasequoia trees), birds (tracks and the marks of beaks probing into mud), fish, burrowing invertebrates (worms and crayfish), even the impressions of scaly dinosaur skin. The numerous fossil bird tracks in Denali, along with being the first of the Cretaceous period found in Alaska and the most northern known to date, present a record of diversity—one of the most diverse fossil bird records yet discovered in the world. Fiorillo and his colleagues have classified one bird track, belonging to a creature larger than a great blue heron, as a new species: Magnoavipes (“big bird track”) denaliensis. The crayfish burrows are interesting because the nearest living crayfish today are found a thousand miles farther south. What it all means is that Alaska’s polar region during the late Cretaceous supported significant biodiversity. “It’s all here,” Fiorillo said, referring to the biodiversity. “It is just phenomenal.” •

We headed up a side canyon and all stopped at another track, a bulbous protrusion on a larger slab of mudstone. This was one Fiorillo hadn’t recorded before, and he took a GPS reading, photographs, and then a full page of descriptive notes. Just in this valley, he told me, he’d so far documented about a hundred tracks—many more elsewhere in the park and probably thousands of trace fossils of all kinds. Venator drew Fiorillo’s attention to another track. “Tell me what you see,” he said to her, “and then I’ll tell you what I see.” “Toe, toe,” Venator pointed. “And this part’s broken off.” “I was trying to see a hadrosaur,” Fiorillo said. “I’ll buy that. “This”—he pointed to another mark—”I don’t know about.” They talked some more, decided they had a single track of a hadrosaur but not a good enough one to document. Higher, Adams was waiting with a theropod track next to a tree cone fossil. I was beginning to develop my own dinosaur eye, and could easily pick out the three long toes—narrower than those of the hadrosaurs we’d examined below. Fiorillo had recorded the track and cone on a previous trip, but he took more photos and then we all sat on a ledge and ate our sandwiches. The theropod, I learned, was a meat-eater, a predator of the hadrosaurs. At least the Denali theropods are thought to have been. Just as “hadrosaur” refers to a large group of plant-eating dinosaurs, “theropod” refers to a large group, or sub-order, distinguished by its bipedal walk on strong legs, bird like clawed feet, small arms with grasping claws, and big tail for countering its weighty head and neck. Theropods are thought to have been fast and agile and to have had good eyesight. They ranged from chicken-size to huge—and included the famed Tyrannosaurus rex. Their fossils have been found all over the world. In Denali, judging from their track sizes, adult theropods were commonly about nine feet long and stood three feet at the hip. From the trace fossils found so far, it’s not possible to narrow them into more specific taxa. On Alaska’s North Slope, where bones have been recovered, four species of theropods have been identified—all of them known from other parts of North America. Linkages between theropods and modern birds have long been studied, and one theropod branch is considered ancestral to birds. At a minimum, many characteristics associated with birds were present in theropods before birds evolved; these included— besides the three-toed foot—hollow bones, a backward-pointing pelvis, and a wishbone in the wrist that allowed a sideways flex and quick snatching motion—a motion almost identical to the flight stroke of modern birds. Some theropods wore feathers. •

The day was getting late. We’d inspected numerous tracks as well as the fossils of plants and crayfish burrows and had reached high and higher ledges. I left Fiorillo and his crew perched on the mountainside, applying pink resin to bumps on ancient rock, and headed back down the canyon. But before I left, Fiorillo told me a little about why the possible pterosaur (“winged lizard”) track was so exciting. The year before, he and a colleague had documented a “hand” print from a pterosaur, establishing for the first time that those dinosaur relatives, the earliest vertebrates known to have evolved powered flight, had been present in Cretaceous Alaska. Pterosaurs not only flew, but were the largest flying animals ever to have lived; Fiorillo estimated the Denali one to have had a wingspan of 25 feet. Pterosaurs had digital appendages at their elbow-bends where the wing folds, and rested on both hands and feet when on land—an attribute that, along with air sacs in their wing membranes, might have helped (by providing a launching mechanism) such a large animal fly. If in fact Fiorillo had now found a pterosaur footprint, that evidence would help build a bigger picture of the animal’s presence in the northern ecosystem. Its presence next to a “baby” theropod track was a bonus. The day before, the team had made molds of a theropod track and then a “baby” hadrosaur foot and hand together. Multiple fossils in the same piece of stone tell a better story than a single fossil alone; a line of tracks from a single animal can tell about its stride, and other combinations tell what lived together or might have been eaten. All through the Cantwell Formation, groups of hadrosaur tracks had been found together, cementing the knowledge that they lived in herds and—based on the many sizes together—that young received extended care by adults. For all the trace fossils thus examined, Fiorillo and his colleagues had found just one small, non-descript bone in the Cantwell Formation. •

This is in contrast to the other Alaska area where Fiorillo has done extensive work—the North Slope, where dinosaur bones have been aplenty. Fiorillo expects they’re there in Denali to be found. He told me, “My thoughts on why no masses of bones have been found is that we’ve still only looked at a small percentage of the exposed rock in the park. One animal can leave many tracks in its lifetime, so the odds favor discovery of many tracks first.” Compared to the softer rock farther north, the hard rock in the Cantwell Formation makes tracks easy to see. The rock quality explained why the area we were in was so fossiliferous. Fossiliferous: my favorite new word. •

When I reached the main fork, near where Fiorillo had shown me the day’s first dinosaur track, I detoured to a site he’d told me about, known as “the dance floor.” I had no trouble finding it on my own. Just beside the path a large rock wall angled out, and the lower surface of it was a rumpled mess. Or that’s what I would have thought before my very recent education. I might have thought it looked like something volcanic, an uneven surface formed by the flow of liquid rock. Now, I knew better. I could see what Fiorillo had described as “like one of those Arthur Murray dance illustrations, with the footprints showing you how to foxtrot.” I could make out a few clear, three-toed tracks, and then it looked to me like there’d just been a lot of big clumsy feet all squishing around on the same soft ground, one footprint obliterating another. I imagined the edge of a waterhole, and a herd of hadrosaurs gathered to drink, or a bank along a stream and the herd thundering past, chased by theropods. After the herd passed, or after many animals took turns coming to drink or to cross a waterway, something—a flood? a landslide?— had covered over the surface, filled and sealed it. Mountains had lifted, mountains had eroded. Seventy million years, give or take a few million, passed. Other people had come to see the dance floor. Their boots had worn a track along the base of the wall; their boots had scattered the larger rock shards and ground the smaller into a smooth surface. I walked up and down that track, studying the wall. I looked closely at one embossment. It looked like a pile of, well, nasty turds, like something a bear that had been eating vegetation might have left behind. It stood out from the other rock to which it was attached, its own abundant and neat assemblage. I was pretty sure it was what the paleontologists call a coprolite—fossilized feces. •

I took my time returning to the road, in a dinosaur daze of thought and emotion. A silver-colored marmot waddling beside the stream stared at me near-sightedly and wrinkled its nose. Dall sheep like snow patches hung on a far mountain. Juncos and warblers darted through the willows. On a knoll covered with blueberries, I stopped to pick some, stepping around berry-studded bear poop. I passed two burdened backpackers headed to the high country. Tourists come to Denali primarily to see “the mountain” and the living megafauna—the “big five” bears, wolves, sheep, caribou, and moose. Now, it seemed to me, the park had a new and important role—to care for and showcase not just today’s magnificent wild environment but to preserve and teach us about the past. Dinosaurs are popular, especially with children, because they’re large, fierce (in myth if not fact), and extinct. That is, you get to be thrilled by them without being in any actual danger. Dinosaurs can’t threaten us, but extinction surely can. As the world warms—and as the Arctic warms disproportionately—we would do well to think about what a warmer Arctic might look like. Fiorillo had said this: “For those concerned about a warming Arctic, the fossils here provide us clues about what that Arctic might look like.” I was one of those concerned. The fossil finds might give us those climate clues, but a warming climate was not going to give us that ancient ecosystem. Nor was it going to favor the current ecosystem, in all its complexity, its finely tuned evolutionary rightness. How will things change in a warmer Alaska? What adaptation mechanisms might help with survival? What migrations might occur? What species might disappear first, or continue longer, or flourish? Less cold, same darkness—who will be the winners and the losers? How will shifts in today’s ecological balance work their way through the whole system? What can we humans do, now that we understand what our heavy tread has done not just to the Earth’s surface and its other living inhabitants but to the systems that support life as we know it, the Earth’s atmosphere, the ocean’s chemistry? We might ask and attempt to answer those questions. Alternatively, we can take the long view—the really long view. It’s been 65 million years since the dinosaurs and much else—more than 50 percent of all animal species living at that time—went missing. The Earth continued; life recovered. It’s just that dinosaurs didn’t evolve again; mammals filled in the emptied niche. And here we are, now, just one more charismatic species, occupying the Earth for our moment in time. After us: other life, algal or floral, skeletal or spongy, with feet or fins or slinky twists, with large brains or small or none at all. And what might remain, more record in the Earth.

She is, after all, a wolf. She is, by nature, aloof. So when she walks by the man who’s wading the creek, boots in hand, she neither slows nor turns her head. Which is not the same as not paying attention. She sees the man startle, freeze midstream with the water running over his pale feet; she sees his mouth fall open. She knows the type. He’s come to the park to partake of its Nature. He hopes to see what the Denali people call “The Big Five”— bears, caribou, moose, sheep, and (least expected) wolves. He hopes to take pictures of all five, to capture them in this modern way—what they call non-consumptive use, as opposed to, of course, consumptive use but, still, just another way of taking. Humans have that need to turn everything in the world into something of their own. They’re worse than greedy pups, and they never grow out of it; everything has to be all about them. Now, behind her, she can hear the man fumbling for his camera. He’s muttering. “Goddamn, goddamn.” Had he really seen a wolf, if he didn’t have a photo? Ha! •

The gray wolf coursing the creek can’t know that less benign brothers (and sisters) of that one barefoot man are at that moment, elsewhere in Alaska, basking in the expansion of the state’s predator control program and (close to home) the removal of a buffer of protected land just outside park boundaries. (Fewer wolves, more moose roasts and caribou steaks for the humans.) That is, the consumptive people were still gaining. She also can’t know that the previous March, over near Alaska’s eastern border, state employees shooting from helicopters killed all four members, including two wearing visible research collars, of a pack that lived in a national preserve and had been studied for sixteen years. And the same month, down on the Alaska Peninsula, two of her kind had taken down a schoolteacher who went running on a lonely road—only the second recorded instance of a fatal (for a human) wolf attack in North America. In that case, the state immediately sent out a plane to gun down wolves in the area, which already “incentivized” wolf trapping with an allowed “take” of ten wolves per person per day. But let’s say she does know all this. Let’s say she’s the dog that is god, the all-seeing, all-knowing. (Not that any wolf wants to be called a dog—or a god, for that matter—but nevermind that.) If she knows these things she will know that, between the competition and the fear and retaliation, now is not a good time to be a wolf. •

The wolf’s hunting ground lies near the top of the pass, near where the creek empties out of a small lake. Snowshoe hares like the willows there, and she likes the snowshoe hares. The hares have enjoyed several peak years, breeding like rabbits (as the saying goes) and the park is littered with their white feet. The lynx and coyotes, the foxes and golden eagles, the wolves— all of them have fattened on hares, and none of them has eaten the boney feet. A slate-colored junco breaks from its bush as she passes, and a butterfly fluttering away from late-blooming cinquefoil draws a snap of her jaws. A flock of ravens rises like a cyclone in the distance: park road, roadkill. Her nose works the air, full of scent old and new, animal and vegetable, the riches of her world. She is a good-looking wolf; she knows this for a fact. Well-fed, bright-eyed, with a fine coat of soft and streaky, nuanced grays. Her thick tail, tipped with black, flags proudly behind her. She stops. She stretches her neck. The clouds in the pale sky look like the backs of sheep. Ground squirrels chirp aggressively, fearlessly, from their burrow entrances. The sun, the breeze, clear water running, willow leaves shimmering in the light: who’s to say wolves can’t enjoy all these, can’t have an aesthetic, even spiritual, experience? An airplane buzzes overhead, and the wolf ignores it as she would a fly. Let’s say she knows—not a great imaginative stretch—that she and the rest of her pack are much-studied animals, tracked by plane through all the seasons, stalked at their dens, photographed in even their most intimate moments. The planes are sometimes followed by the great whirring helicopter-beast, its side open like a wound, a man leaning out—coming closer, lower, closer, louder—with the stick that shoots the sting that knocks away all sense. This she’s seen: members of her pack collapsed like rags, tongues hanging out, men shoving them around, attaching those god-awful collars. She knows the terror of the chase, the pack scattering, the howling from the shadows. But men (and women too) must do their studies, collect data, know where the wolves go so they can manage them. They’ve counted: 59 park wolves (in spring, before the season’s pups), twelve packs. This is down from 130 in 1990, an average of 92 between 1994 and 2005. Winters decide. Hard winters are hard on the ungulates, generous to the wolves. Easy winters, the caribou, moose, and sheep all run away, fold less often to starvation. Those same studious people track the transmitting collars. They know when the wolves leave the park boundaries (those imaginary lines) and when they return. They know when they signal from stillness: death by moose kick, by the skull-crushing bite of another wolf, by trapper. They go look, if they can, at dead wolves and take away their collars; this is how they decide that a majority of all park wolf deaths come at the jaws of other wolves, in territorial disputes. Wolves, more often than not, can outsmart wolf trappers. They’ll avoid traps—the crushing steel legholds, the wire snares. This is why predator controllers need airplanes and shooters; the trappers are too few, too inefficient. In all of Alaska, there are some eight to ten thousand wolves. Every year more than a thousand are “removed.” This is called managing for abundance. The wolf, with her educated imagination, keeps trotting up the creek. Grant her the knowledge of numbers, of facts and contradictions, of conflicting jurisdictions. Grant her memory: the wolf that returned with steel wire cinching his neck, cut deeply into flesh. She and the others licked the wound. The injured wolf’s neck swelled. Its muzzle and face and eyes swelled. Then, the helicopter came. The humans and their tools removed the wire. Our omniscient wolf is panting now. Say she knows, remembers, imagines all that; say she’s as smart as a chimpanzee. Still, her powers go only so far. She can’t imagine how any of that makes sense. One man tries to kill a wolf by strangulation. Other men go to great effort and expense to save the same wolf. What do men want? Just ahead, a turned-away ground squirrel feeds distractedly, tearing at grass. The wolf slows, studies the quivering curves of shoulder and side. A few more light steps and she launches like a spring, closes her mouth on the rising head. •

In the evening, when she returns to the den site, the year’s pups swarm to her. She arches her back and regurgitates their steamy meal. The pups’ mother, sprawled at the edge of the bluff, lifts her head. When she drops it again, the battery pack portion of her collar clunks on the hardened ground. She—the dominant female—and her mate wear the collars in the pack, as do the breeding pairs in most of the other park packs. They have been singled out for this honor by the humans who study them. What the humans have learned impresses them (the humans.) They can hardly believe how cooperative wolves in a pack are. They see that wolves hunt together with actual strategies, and that they share food. They spy on the social rituals, the acts of dominance and submission, the care lavished on the females with pups as well as the pups themselves, the discipline meted out. They ponder what they call “cooperative breeding”: the fact that, in a pack, only the dominant pair has young, and the other adults assist with their care, something like aunts and uncles, like members of a family. Of course, the gray wolf knows, they are a family; why is that so hard to understand? When the shooters and trappers kill the parent wolves, the social structure of packs is broken. No surprise there. Young pups are left without sufficient parenting, fail to get their full instruction in how to succeed as wolves. Other wolves in the pack—and sometimes wolves that move in from other packs—negotiate their status and roles, settle on who mates with whom. As long as there’s enough food, the new pair will produce enough pups to replenish the ranks, in short order. This suggests, to a cognizant wolf and at least some humans, that the millions of dollars spent on government wolf control are a waste of money and certainly not worth the bad press. When it’s people howling, you’ve definitely got a problem. •

The next morning, early, the six adult wolves hunt in the valley. They stream down its middle single-file to reach three caribou separated from a larger herd. They gather themselves there—splitting up, three taking a run around one side, two the other way, one holding in reserve. They run the caribou this way for an hour, rejoicing in the stretch, the scent, their muscled leaps above the brush as they survey the scene. They slip close to, then fall behind the smallest (but fleet) caribou, and they reconnoiter and try from another direction, dividing into a new constellation, more circling, the always- testing that is their way. The caribou with clacking hooves flee over the plain, toward the hills. The wolves, finally, trot back along the braided river bottom. The river intercepts the park road, and the gray wolf and a brother climb up onto the gravel track and walk along it. They’re tired from the chase, and the road represents the easiest of paths. Before long one of the park buses motors up behind them with grinding gears and a great cloud of dust. It’s no threat, and they ignore it. It creeps along behind them, and they’re aware of the sound of windows sliding down and snapping into place, then the clicking and whirring of flocks of cameras. The gray wolf looks behind her, sees fleece-covered arms, wedges of face, the round eyes of all those cameras. They’re flashing like sparks from a fire, or like the sun reflecting on moving water. The two wolves trot on. Another bus, in another cloud of dust, approaches from the other direction, stops a long way off. The wolves continue toward it, see the movement inside, its people standing, crowding forward, more windows sliding and snapping, voices now. The bus driver is saying, “You’re incredibly lucky to see this. Of the five big mammals in the park, wolves are the ones you’re least likely to see. They’re the emblem of true wilderness and play a very important balancing role in the natural ecosystem.” Other voices: The gray wolf has seen and heard this all before. She’s not averse to following the road when it’s going her way, and she’s gotten accustomed to passing the buses or even people on foot, giving them all a thrill. If she knew the park management disapproved of this fearlessness, this less-than shy wolf behavior, she wouldn’t care. If she knew that the chairman of the Alaska Board of Game, one who’d been happy to get rid of the protective buffer at the edge of the park, had referred to the Denali wolves as “mangy dogs walking down the road,” she might or might not have been offended. These days she let a lot roll off her back. If she knew that wolf lovers had made a CD of wolves howling, something they called Wolf Songs, and that a trapper just past the park boundary played it to call in and shoot wolves, she might have wanted to chew the arms off of every one of those crazy humans. The two wolves are past the buses now, two buses stopped in one direction, one in the other, a wolf jam waiting, the people with their heads down, looking at the pictures they’ve taken. Overhead, a golden eagle floats. Clouds gather on the far-off mountains. The gray wolf steps off the road, into her lucid world. Nancy Lord, Alaska’s Writer Laureate (2008-2010), holds a liberal arts degree from Hampshire College and an MFA in creative writing from Vermont College. In addition to being an independent writer based in Homer, she fished commercially for many years and has, more recently, worked as a naturalist and historian on adventure cruise ships. She is the author of three short fiction collections (most recently The Man Who Swam with Beavers, Coffee House Press, 2001) and four books of literary nonfiction (most recently Rock, Water, Wild: An Alaskan Life, University of Nebraska Press, 2009.) She teaches part-time at the Kachemak Bay Branch of Kenai Peninsula College and in the low-residency graduate writing program at the University of Alaska Anchorage. Her awards include fellowships from the Alaska State Council on the Arts and the Rasmuson Foundation, a Pushcart Prize, and residencies at a number of artist communities. Visit Nancy Lord's website. |

Last updated: March 7, 2019