Research Report

Discovering Layers of History at the Royal Presidio Chapel

by John D. Lesak, Benjamin Marcus, and Michael Tornabene

In the fall of 2007 several layers of decorative finishes, including classically inspired mural paintings, were uncovered at the Royal Presidio Chapel, a mission-era church constructed c. 1794 in Monterey, California.(1) Found during a seismic retrofit beneath a layer of wire lath-reinforced, Portland cement-based plaster, the artistry almost certainly dates to the chapel's original construction. The fortuitous discovery contributes significantly to the knowledge of decorative wall-painting during California's Spanish Colonial period. The fresco techniques, workmanship, and polychrome motifs evidence Spanish influence of the late 18th century. Although wall-painting from this era is not unheard of, this level of artistic sophistication and classical training is rare. The motifs visible at the chapel are unique among extant buildings of colonial New Spain for their age, classical influence, and refined technique.

Designated a National Historic Landmark for its significant representation of California's colonial history, the Royal Presidio Chapel has been studied extensively. The Historic American Buildings Survey recorded its architectural form in 1934; investigations with a more exploratory mandate followed. These included archeological investigations, an analysis of the stone façade, examination of interior finishes, and a historic structure report. Analyses of the building's interior finishes indicated that the original interior was unadorned. Conservators sought to confirm this assessment in spring 2007 by making limited openings through the cement plaster. They found rubble masonry from the exterior walls directly underneath.

During seismic rehabilitation in October 2007, plaster treatments were removed from the chapel's exterior. This exposed original (but later in-filled) window openings and forever dispelled the long-held view of the chapel's first "simple and unadorned" appearance. The jambs of the windows featured brightly painted surrounds that mimic large, ochre-colored stone blocks. Within days, contractors discovered a painted valance at ceiling height. This led to the uncovering of complex and vibrant frescoes and finishes.

Paralleling California History

The history of the Royal Presidio Chapel parallels that of California: settlement and cession by the Spanish, transition to Mexican rule in 1821, secularization in 1835, and annexation by the United States in 1849. Originally constructed as a military church in a basilica style, the structure was expanded with the addition of a transept and apse in 1858 and remodeled.(Figure 1) In 1942 architect Harry Downie Jr., attempted to return the interior to an austerity then associated with the Spanish Colonial aesthetic by removing or hiding the Victorian-era alterations and many previous decorative schemes behind wire lath-reinforced cement plaster.

|

Figure 1. The exterior view of the Royal Presidio Chapel shows the building before beginning the seismic retrofit campaign. (Courtesy of the authors.) |

That wire lath proved to be the greatest impediment to uncovering the interior finishes. The steel rapidly dulled the tools used on the cement plaster. Nonetheless, buoyed by the discovery of a decorative valance adjacent to the ceiling plane, a series of inspection openings were inserted through the cement plaster to determine the extent of the historic finishes. These openings were located strategically per their relationship to the confessional, sacristy, choir loft, nave, and bell tower. Each revealed up to four decorative finish campaigns varying in technique and color.

Investigating the Decorative Finishes

The unexpected number of decorative campaigns and their complex, pictorial nature led conservators to implement a methodology based on strategic, but invasive, openings in the wall fabric, meticulous plaster removal, stabilization, and sampling, and documentation of all work done. The locations were determined by earlier studies and on the results of those investigations; that is, if decorative elements were found on the east wall, an opening in the similar location would be made on the west. Locations for the exploratory openings were also guided by the likely position of architectural elements as well as by the iconography of other missions.

Scored first, the individual squares of plaster were removed by hand, exposing the friable decorative finishes in the process. The finishes were then stabilized using chemical consolidants along with edging and injection with natural hydraulic lime grout. Each layer at any given opening was documented in-situ through hand-tracing, archival digital photography, and color-matching to the Munsel standard. The exposed decorative finishes were carefully sampled for use in laboratory analysis; layers of the different decorative finish campaigns were carefully removed by hand with dental tools, wooden scrapers, and brushes. Finally, as the openings revealed specific decorative elements, they were enlarged to completely document the element. Each opening was sized, measured, and referenced to datum points.

Using this exploration technique, the conservators conducted a comprehensive investigation of the chapel's interior. Initial work near the confessionals and transept uncovered an arch-shaped holy water receptacle surrounded by floral decorations and crosses and a vibrant diamond-patterned dado border executed in a surprisingly rich color palette. Further analysis revealed intricate architectural ornamentation and decorative figure painting executed in a variety of finish techniques.

Conducting Laboratory Analysis

Physical on-site exploration, investigation, and laboratory analysis of the paint samples elucidated the composition of the paints and stratigraphy of the layers, which corresponded to various repainting campaigns conducted between 1794 and 1858. At least four schemes were found, including multiple layers of whitewash between the decorative layers, and were identified through cross-sectional microscopy.(Figure 2)

|

Figure 2. Microscopic analysis revealed three finish layers and two layers of whitewash applied between finish campaigns. (Courtesy of the authors.) |

Laboratory characterization of the paints was conducted by the Getty Conservation Institute. Analysis revealed mineral and organic colorants commonly used in the 18th century. These included burnt organic materials, such as bones and wood, to make blacks and grays, hematite and maghemite used to make reds and pinks, and goethite for the ochre color. The presence of these colorants, which have been found in paintings of the period, confirms the early date of the chapel's frescoes.

Picturing the Historic Paint Schemes: 1794-1858

With the on-site exploratory investigation and laboratory analysis completed, the project team constructed an overall picture of the church's interior appearance as it evolved over time. The original layer, incised and applied wet as true fresco, was the richest period of decoration with a classical colonnade, dado, valance, ornamental window surrounds, and portraiture. The colonnade consists of a pair of Corinthian columns painted on each nave wall, surmounted by a multicolored, faux-stone tri-centered archway that mimics the carved portal of the church's primary façade.(Figure 3) This classically influenced architectural ornamentation framed the original sanctuary area, separating it from the comparatively unadorned nave.

Wood members, wrought iron spikes, and plaster outlines found above the column capitals suggest that the painted columns visually supported a wood arch likely removed before 1858. At floor level, the dado of a scarlet and pink diamond pattern defines the former sacristy.(Figure 4) The upper walls of the church featured a valence made of an intricately painted striped faux fabric capped by an interlocking banderol pattern. Employing a rich color palette, the window surrounds of the exterior continued on the interior, where the faux stone blocks are finished with decorative corner flourishes and floral motifs. A circular floral motif articulates the center keystone of the faux flat arch.

|

Figure 4. The diamond dado served to define the sacristy. This full-height border appears to have extended to the floor, but rising damp has damaged the bottom 18 inches. (Courtesy of the authors.) |

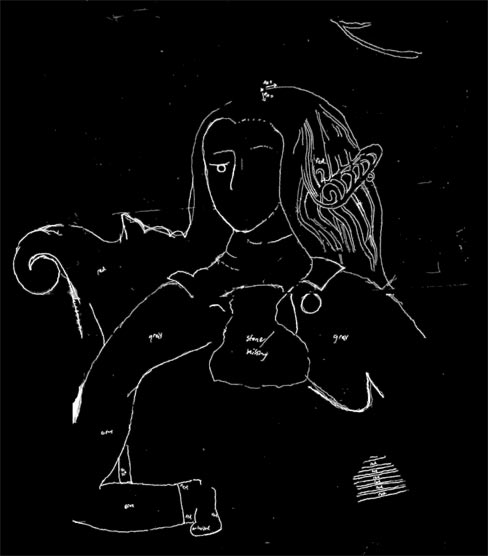

Perhaps the most significant find from the primary paint layer is a portrait of a red-haired woman on the wall of the choir loft. Although damaged by centuries of water infiltration and soot, it clearly shows a woman with curly bright red hair, with her head turned to the right, with distinct facial features and clothing.(Figures 5, 6) The style of the portrait resembles figures carved into the stonework of the church's transept doors and appears to be the earliest such painted representation in colonial California.

|

Figure 5. The view of the female figure portrait shows damage from years of water infiltration and previous construction campaigns. (Courtesy of the authors.) |

|

Figure 6. A trace of the figure painting reveals what appears to be the top of a throne, the angle of her arm, and her decorative clothing. (Courtesy of the authors.) |

Although focused on the decorative finishes of the oldest layer, further analysis of the subsequent three layers yielded significant information. The second-oldest scheme includes an orange dado with black band painted on a layer of whitewash. A third layer corresponds to a drastic shift in coloration and techniques. Devoid of vibrant colors, it features black and white stenciled floral detailing and gray accent lines. Original ochre-colored faux-stone window surrounds were covered with gray faux-stones, creating an interior that may have been painted entirely in shades of black and gray. The fourth scheme exhibits a single solid layer of ochre appearing only at the dado level.

Building on this Discovery

The discovery of original frescoes has enriched the interpretation of the Royal Presidio Chapel, answering many questions about its construction, alteration, and appearance. Interpretive windows in the new finish plaster expose select painted borders, architectural elements, and decorative figures. Peeling back the layers of paint and displaying pieces of the early ornamentation not only offers a better understanding of the paint schemes but also of the chapel's own multi-faceted history.

The frescoes were the highlight of the 4th Annual Historical Preservation of the Royal Presidio Chapel Conference, hosted by the Chapel Conservation Project in the fall of 2008. Through this forum, team members provided an extensive update of their respective areas of work and the ensuing discussions amplified the dovetailing of the disparate evidence uncovered thus far. Conservators hope further study of the frescoes will allow them to "bracket" the four decorative schemes. This next phase will entail an interdisciplinary approach involving study of the iconography of the chapel and placing its motifs within the context of the California missions. In-depth analysis of materials and artistic techniques employed in the paintings, combined with research of the chapel's imagery, promises to add much to the subject of Spanish Colonial wall-painting in North America.

Across Four Centuries of Change: a Timeline

| 1769 | "Sacred Expedition" to colonize Alta California begins, teaming Franciscan missionaries with the Spanish military. |

| 1770 | Father Junípero Serra arrives at Monterey Bay and on June 3rd dedicates the Mission San Carlos Borromeo, southeast of present-day Monterey, the second of what would total 21 California missions. Three chapels are built in subsequent years, each destroyed by fire. |

| c. 1771 | Father Serra moves the mission to Carmel. The existing chapel near Monterey becomes part of a Spanish military post, a presidio, headed by a military governor and the King of Spain, who has claimed Monterey as the capital of Alta California. |

| 1791 | Construction of the fourth chapel begins on the site. Opening in 1794, it becomes the Royal Presidio Chapel the following year. Now a National Historic Landmark, it is the sole extant structure of the Monterey presidio established in the 1770s. |

| 1821 | Mexican War of Independence is victorious against the Spaniards (who call it the Mexican Revolution), and the Royal Presidio Chapel is now in the hands of the independent Mexican government. It falls into disrepair under military rule. The Chapel is transferred to civil jurisdiction in 1835. |

| 1846 | Congress declares war on Mexico, and the U.S. soon occupies Monterey. U.S. wins the Mexican-American War in 1848. California, part of the Mexican Cession, declares U.S. statehood in 1850. |

| 1858 | Chapel expansions include a transept and apse, reflecting the early prosperity of Monterey. The interior is remodeled to reflect Victorian taste. Alterations to the interior include covering the original beams of the ceiling. |

| 1942 | Architect Harry Downie Jr. leads ambitious restoration seeking to seismically strengthen the Chapel and return it to a Spanish Colonial aesthetic. |

| 1950s | The first of many archeological studies is conducted at the site. |

| 1995 | Funded by the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, study of the façade's decaying stone initiates a decade-long period of investigation, research, and analysis. |

| 1999 | Historic Structure Report undertaken by a team of conservators and historians, headed by historian Edna Kimbro. |

| 2006 | Diocese of Monterey announces $7.2 million Chapel restoration campaign including seismic strengthening, interior rehabilitation, and façade conservation. |

About the Authors

Principal John D. Lesak, AIA, LEED AP, an architect with an interdisciplinary background in engineering and materials science, leads Page & Turnbull's Los Angeles office. Michael Tornabene, Assoc. AIA, LEED AP, is a designer in the firm's Building Technology and Conservation studio in San Francisco. Ben Marcus is a conservator in the same studio in Los Angeles.

Note

1. The project team consisted of the Diocese of Monterey, owner; Cathy Leiker, project manager; Franks Brenkwitz & Associates, architect; Anthony Crosby, architectural conservator; Page & Turnbull, preservation architect; Fred Webster, structural engineer; and Webcor, general contractor.