Article

The Kingsley Plantation Community in Jacksonville, Florida: Memory and Place in a Southern American City(1)

By Antoinette T. Jackson

Now, who was Anna Kingsley? The shero who connects me most pointedly to where you are seated and I stand, is Anta Majigeen Ndiaye Kingsley, known to us as Anna Kingsley. It is my maternal line that makes me a descendant of the Kingsley's. [Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole — Keynote address, 11th Annual Kingsley Heritage Celebration in Jacksonville, Florida, February 21, 2009] |

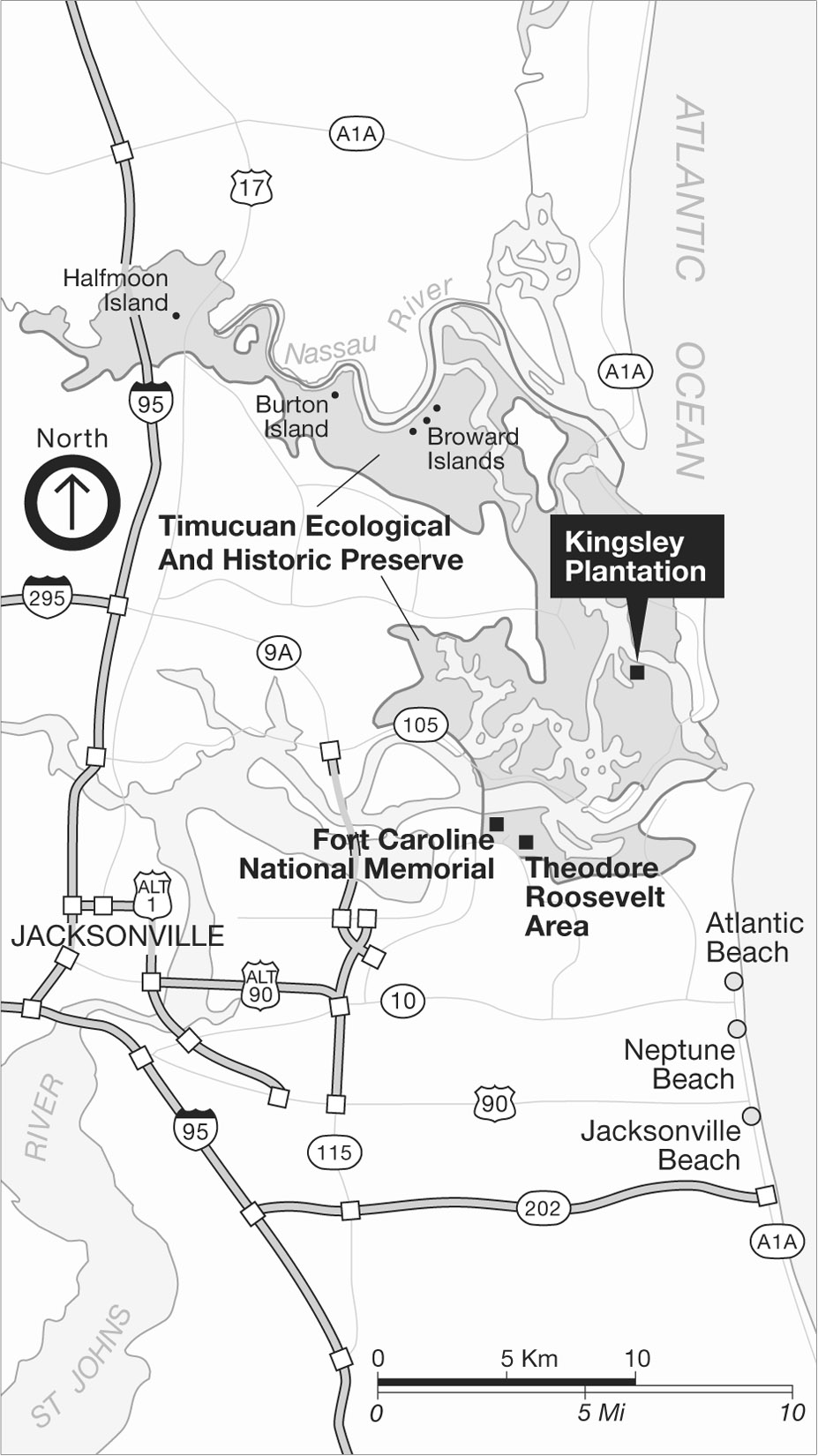

The Kingsley Plantation is located in Florida east of Jacksonville at the northern tip of Fort George Island at Fort George inlet. (Figure 1) Control of the island alternated between the Spanish and the British before being purchased by Zephaniah Kingsley Jr. in 1817 during the second Spanish Period of control. Today, the plantation is part of the National Park Service's Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve. (Figures 2, 3)

|

Figure 1. Map of Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve and surrounding area. (Courtesy of National Park Service.) |

The history of the Kingsley Plantation is an interesting and complex combination of people, personalities, and agendas. Kingsley was a wealthy planter, businessman, and slave trader, who was born in Bristol, England, in 1765. The life and business activities of Kingsley and Anta Majigeen Ndiaye (Anna Kingsley), born in Senegal, West Africa, in 1793—who he purchased, fathered children by, and established households and businesses with in Florida and Haiti—underscore the reality of the transatlantic slave trade from the perspective of a specific family. The Kingsley's multi-racial, multi-national family and their associations on local and global levels provide insight into the complexity of meanings and experiences attached to place and the fluidity of identity formation within and outside of plantation landscapes in America.

This article uses ethnographic interviews to reflect on the importance of particular places to descendant and local communities coming to terms with the legacy of slavery and segregation. The focus is on the Kingsley Plantation community and shared family connections to places in Jacksonville, including American Beach, as well as the plantation itself. Such places provide a window to the past not only as tangible or physical markers but also as cultural signifiers. They maintain their relevance through the meanings associated with them.

There is an abundance of Kingsley myths and stories.(2) However, the central theme of "the Zephaniah Kingsley story" is his acknowledged spousal relationship with Anna Kingsley, described as being of royal lineage from the country of Senegal. Anna is thought to be one of three bozales: newly imported people from Africa whom he purchased and transported from Havana, Cuba, to Florida in 1806.(3) According to Zephaniah's own accounts, he married Anna in accordance with her native customs and established a home with her at his plantations in East Florida (Laurel Grove and Kingsley Plantation) and later in Haiti. They had four children: George, Mary, Martha, and John. Anna Kingsley also is recorded as having owned plantations as well as enslaved Africans and many accounts of the Kingsley story incorporate this perspective.

Who is Anna Kingsley and what makes her central to understanding the complexity of the descendant community and its relationship to the Kingsley Plantation? The question of Anna Kingsley and her centrality today was poised by Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole in her keynote address to the 11th annual Kingsley Heritage Celebration in Jacksonville on February 21, 2009. Dr. Cole is a self-identified African American woman, a seventh-generation descendant of Anna and Zephaniah Kingsley, a trained anthropologist, and a former President of Spelman and Bennett Colleges. In the opening remarks of her talk entitled, "Sankofa: Looking Back to Go Forward," Cole declared Anna Kingsley her shero, a female hero of special note because of her gender and the obstacles of extraordinary size and scope that had to be overcome in order to achieve her desired goal. In the case of Anna Kingsley these obstacles included slavery, racism, sexism, and patriarchy in the 1800s. Standing on the grounds of the Kingsley Plantation, a place she described as difficult for her to visit, Dr. Cole encouraged the enthusiastic and attentive audience to consider making Anna their shero as well. Cole said—

She's a shero for me. Obviously the park service thinks so. They invited you here to understand not only about Zephaniah Kingsley but to understand about Anna Kingsley. She is a shero. But I have to ask you, should we remember her as a slave or should we deal with the fact that she was a slave owner? Wasn't she both? Was Anna Kingsley an African or was she an American, or was she both? Were her children, the four sired by Zephaniah Kingsley, were they white or were they black or were they both? Countless lessons I think. All of us are doing our best to learn from being in this extraordinary, this exquisite moment of American history and the history of the world. |

Dr. Cole's provocative descriptive of Anna Kingsley frames the theme and urgency of this discussion. In her timely analysis of Anna Kingsley's identity, Cole highlights the past as a means of informing ways to move forward. The Kingsley Plantation and community provide unique and explicit examples of dynamic and multiple constructions of identity and experiences of place. They provide a model for looking back in order to move forward.

Oral history and interview testimony provided by Zephaniah and Anna's African, European, and Latino descendant family members and descendants of enslaved and free persons of color and others associated with the Kingsley community provide an important perspective for understanding the significance of place. Because the Kingsley Plantation community includes not only the physical site of the plantation, but also the associated community, it extends well beyond the physical boundaries of the Timucuan Preserve and includes all of the places where Kingsley descendants and others associated with the plantation live and work today.

The Kingsley-Sammis-Lewis-Betsch Family and Community Associations

The Kingsley Plantation community today is embedded in the fabric of everyday life in Jacksonville and its surrounding communities. The experiences of the Kingsley-Sammis-Lewis-Betsch family offer an intergenerational accounting of the role that varying experiences with, and connections to place, play in shaping our understanding of the past and framing the way we think about the future.

In 1884, Abraham Lincoln Lewis (1865-1947) married Mary F. Sammis (1865-1923) who was the daughter of Edward Sammis, a Duval County justice of the peace; the granddaughter of Mary Elizabeth Kingsley-Sammis and John S. Sammis; and the great-granddaughter of Zephaniah and Anna Kingsley.(4) Or perhaps a better way to think about the Kingsley-Sammis-Lewis family genealogy is the description given by Dr. Cole. She shared her family's genealogy in this way—

Well, Anna Kingsley was my maternal great-grandmother Mary Sammis Lewis' father's grandmother. Now if you are an anthropologist you could figure that out. Put it another way, Anna Kingsley's grandson whose name was Edward G. Sammis married a woman whose name was Lizzy, who was sometimes called Eliza Willis Sammis. Their eldest daughter, are you with me? ... You got Anna Kingsley and you got her grandson. What's his name? [She asks the audience then continues] Edward G. Sammis. He marries… Eliza, they have children, their oldest child was Mary Sammis-Lewis. Who was she? [She asks the audience then continues] She married Abraham Lincoln Lewis, who is my great grandfather. You just got your PhD in Anthropology! |

The Abraham Lincoln (A.L.) Lewis and Mary Sammis Lewis union formed one of the most prominent dynasties of wealth, influence, and power in Florida's African American community. A.L. Lewis, one of the founders and later one of the presidents of the Afro-American Life Insurance Company (the Afro), became one of the richest men in Florida during the 1920s and remained so until his death in 1947. He amassed large amounts of property in Jacksonville, and throughout Florida, and operated many successful business ventures. Mary F. Sammis-Lewis was also very active in the Jacksonville community. Among her many civic, social, and business activities she served on the Deaconess Board of her church, Bethel Baptist Institutional Church, for over 20 years. Marsha Phelts, author of the book, An American Beach for African Americans, published in 1997, grew up in Jacksonville, and knew members of the Lewis-Betsch family personally. She shared the following perspective of the family—

they were people that we loved to watch and loved to read about, to hear about . . . They were extremely admired and respected. They were the middle-class. Credit Randolph with the middle-class in America because what he did for the Pullman porters in terms of organizing and union and bringing their pay up but in this little corner of Jacksonville, the Afro-American Life Insurance Company was certainly responsible for a big portion . . . If you had a middle-class status as being an executive for the Afro, there certainly was that to be enjoyed, and they mortgaged homes during a period that established places did not provide mortgages that very much. Established places did provide mortgages but they were harder to come by and so the Afro and the Lewis' made great contributions, they really did.(5) |

Racial segregation policies in America prior to 1964 resulted in restricted or very limited access to beach recreation for people labeled as Negro. A.L. Lewis and the Pension Bureau of the Afro-American Life Insurance Company developed a total beach community for African Americans, known as American Beach. It served to counter restrictions imposed on African Americans by segregation laws and policies. American Beach is north of Jacksonville in the Amelia Island area. (Figure 4) Marsha Phelts explains the importance of American Beach to the African American community in this way—

My family is from Jacksonville, and so American Beach is an extended part of the Jacksonville community, it's just 30-40 minutes to an hour away from Jacksonville, and this is where black people came during my growing up and my youth for the beach. This was the beach, even though the coast [of] Duval County has a beach coast, but that was not available in the 40s and in the 50s, only in 1964 were blacks able to go to the beaches, and all of the beaches were open to them. I was born in 1944, so I would have been 20 years old if it hadn't been an American Beach for me to come to. Because of this beach I have been coming to the beach my whole life.(6) |

Prior to the establishment of American Beach, African Americans in the Jacksonville area frequented Pablo Beach (now Jacksonville Beach) which was opened in 1884 to African Americans on Mondays only and Manhattan Beach located near Mayport, now occupied in part by the Mayport Naval Station.(7)

|

Figure 4. American Beach Marker and Commemoration to A.L. Lewis. (Courtesy of the author.) |

A.L. Lewis and his family as well as others in the African American community owned homes on American Beach. For many years this beach resort community served as the hub of recreation and entertainment for families and civic and social organizations throughout the South. Dr. Cole describes her American Beach experiences in this way—

. . . and when the big Afro picnics would happen once a year, I have just gorgeous memories of my father making his own barbecue sauce and barbecuing there… . It was in my view what community could really be about, that is folk caring for each other, sharing what they had, going beyond lines of biological kinship to feel a sense of shared values, and one must say also, to feel a sense of shared oppression. Because it was clear to everybody that while A.L. Lewis in his wisdom and with his wealth had made sure that that beach was available, not just for his family, not just for the Afro, I mean people now live in Virginia, in North Carolina who remember coming to that beach. But everybody knew that we were on that beach and could not be on the other beaches.(8) |

Prior to her death in 2005, MaVynee Betsch, Cole's sister, had an informal museum on American Beach and conducted impromptu tours for anyone who showed up on the beach. (Figure 5) In a 1998 interview she said that sometimes people would be lost on the way to Amelia Island Plantation, a more upscale resort, and they would end up on American Beach, "…and I['d] jump in the backseat and give them one of those tours. What! American Beach. We've never heard of it."(9)

|

Figure 5. American Beach, August 2001, Black Heritage Tours by the Beach Lady sign. (Courtesy of the author.) |

The experiences of Kingsley descendents highlight the conflation of race and class which often occurred in the face of legalized segregation in America for African Americans. This was because anyone racialized as black, or labeled as non-white, was subjected to the same physical and social segregated place restrictions regardless of wealth or class. Uplifting, defiant, and frustrating in many ways, these memories of place experiences are poignant reminders of the cultural complexities of navigating race, place, and class in America in the aftermath of the transatlantic slave trade and especially during Jacksonville's period of segregation.

The Kingsley Plantation: A Physical and Social Reminder

The remaining physical spaces of the Kingsley Plantation as it existed at the time of Kingsley's ownership includes the 'big' house, Anna Kingsley's 'kitchen' house, a barn, slave cabin remains, and approximately 720 acres of land and waterway access via the Fort George inlet. (Figure 6) In 1955, the state of Florida acquired the Kingsley Plantation, and in 1967 started restoring the plantation to the Kingsley period (1817-1843). The slave cabin remains provide a visually arresting reminder of the institution of slavery practiced in northeast Florida and throughout the U.S. South.

In 1991, the National Park Service took possession of the Kingsley Plantation complex. It is here that Kingsley's descendants and others connected to or interested in the plantation gather for the Kingsley Plantation Heritage Celebration, an annual event sponsored by the National Park Service. The Heritage Celebration offers multiple perspectives of the Kingsley Plantation and generates new ways of knowing about the meaning of the plantation site today. It attracts many first-time visitors to the plantation grounds. Participants report that they attend in order to learn more about the plantation's history, to remember and acknowledge those who lived and worked on the plantation, and to meet other members of the Kingsley Plantation community.

The first heritage celebration at the site was held in 1998, based on an idea presented to the National Park Service by Kingsley descendant, Manuel Lebron, who was born in the Dominican Republic. The 1998 National Park Service-sponsored Kingsley Plantation Heritage Festival and Family Reunion brought together Kingsley family members from as far away as the Dominican Republic and as close as St. Augustine and Jacksonville. Interviews of many of the reunion participants were conducted and videotaped by University of Florida graduate students.(10) Stories told by participants provide insight into issues of history and heritage with respect to the Kingsley Plantation site; and provide insight into a wide range of feelings about, or connections to Zephaniah and Anna Kingsley.

For example, George W. Gibbs IV, a self-identified European American Kingsley descendant of the Isabella Kingsley-Gibbs family line, or Zephaniah Kingsley's sister Isabella's family line, expressed his thoughts about his great- uncle's business operations in this way—

This was pure and simple a place for Zephaniah Kingsley to bring slaves in his ships to Fort George, and they tied up here and they disembarked here at Fort George, and they began the domestication, if you will, of the African slaves he had brought to America or to Florida for the purpose of training on this site and selling them, moving on and selling those slaves. This was all about slave trading. This was not about—this was not a tobacco plantation where Zephaniah sat up here in a straw hat and corn cob pipe and watched his crops grow and harvested them every year and made money. His business was—he was in the slave trade business on this site. |

Becky Gibbs, also a self-identified European American Kingsley descendant of the Isabella Kingsley-Gibbs family line, reflected upon her ancestral heritage and what it means to not only be a descendant of a slave owner, but also, a descendant of a slave owner who publically acknowledged spousal relations and fathered children with African women. She articulated her feelings in the following passage, contrasting her way of experiencing things with those of her father's and her uncle who were born the early 1900s—

But I've also wondered about the dilemma of growing up in a white southern family, having black ancestry, we're people of the nineties, so we, I look at this as really exciting, wonderful, sort of it opens the doors. But when you come from Jacksonville, a southern town, and you . . . were born in 1911, and you grew up in the South, it must be a big dilemma having ancestors that were not only slave owners, but they also married their slaves and had children. |

In general however, when interviewed, Kingsley family descendants who attended the festival and reunion emphasized the significance of family connections made at the event. For example, descendants Sandra LeBron and her son Manuel LeBron from the Dominican Republic stressed the unity of the family and a desire and willingness to personally forget negative aspects of the past and concentrate on establishing positive relationships in the present. Sandra and Manuel trace their connection to the Kingsley family through John Maxwell, one of Zephaniah and Anna Kingsley's sons, who established his home in the part of Haiti which is known today as the Dominican Republic. According to historian Dan Schafer, around 1837 Kingsley sold most of his Florida property and resettled his extended family in Haiti because the laws there were much less restrictive for people of color. This included Anna Kingsley and her sons George and John Maxwell and a host of others.(11) Manuel expressed his feelings about a family inheritance dispute between Anna Kingsley and one of Zephaniah's sisters, Martha Kingsley-McNeill, in this way—

Yeah, because, you know, the celebration was going on and like, I, for myself didn't have any, any, any, whatsoever, any you know feelings of regret or hate or anything like that—not at all. . . . As I said, you know, it's delicate issues that you have to laugh them off because there's nothing else to do, and you know, it would be stupid to have any bad feelings because it's past. You just laugh it off and forget it completely. |

Finally, Harriet Gibbs Gardiner, a fifth-generation, self-identified European American descendant of the Isabella Kingsley-Gibbs family line, describes her memories of the past and her relationship to the Kingsley Plantation site—

We used to do this with all children—when we'd come out here [to the Kingsley Plantation], we'd look around and then we would go and stand there where you can look across to the marsh and the trees beyond and we would think what it must have been like to see a slave ship coming in or maybe see that long boat rowed out and use your imagination. This is a wonderful place for imagination because it's unspoiled and not a lot of buildings around, and so you can go back in history. So, that's something that I still like to do—stand out there and look at the marsh.I'm so happy that I hope this is the beginning of a coming together of the descendants of two families that have been separated for so long and really not because they're willful about it, but just because they haven't realized how much richness there is in this whole experience under this roof and in this locale. I've always loved Fort George Island and it's always had a special meaning right here, but now it's even more so. |

In the case of the Kingsley Plantation, the Kingsley Plantation Heritage Celebration is a mediating space, or a non-threatening social place, for members of the Kingsley family and others to share memories about, or reconcile their own contradictory and varying identities and relationships with, the Kingsley plantation and its history from just before the antebellum period to the present.

In 2001, I conducted in-depth interviews with members of the Kingsley Plantation community, including interviews with two self-identified African American descendents of Anna and Zephaniah Kingsley: Peri Frances Betsch and Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole. They were very direct in analyzing their relationship to the Kingsley legacy. Peri Frances is on a personal mission to find out more about her family's ancestral connection to Anna Majigeen Ndiaye. She says that she does not find those storybook romance portrayals of Anna's arrival as an enslaved African woman and life as mistress to Zephaniah Kingsley very believable. An eighth-generation Kingsley descendent, she shared the following ideas and feelings regarding the circumstances of her great-grandmother's (Anna Kingsley) arrival in Florida and the initial encounter between Anna and Zephaniah—

Sometimes it makes me laugh. But I don't think it was like some . . . 'I saw him across the crowded slave market, and he winked at me', that's ludicrous. I can't buy into that. And also you got to think like I would imagine, these people looked crazy to her, like who are you? I imagine some redheaded white guy with a beard, wearing funny woolen clothing, and she must have been like . . . 'You want me to do what?' I just can't picture it. But I really always wonder what was she thinking.(12) |

Cole, a seventh-generation Kingsley descendant expresses her feelings about the complexity and multiple identities that characterized her great- grandmother's life as an enslaved African woman, as a free woman of color and wealth, and as an eventual owner of enslaved Africans herself in this way—

It is obviously a profoundly moving story. It's also a story, which in my view has extraordinary complexity and contradictions. My great-grandmother was not only a slave, she owned slaves. And, I would hope that for each of us as an African American, if there is any specificity to what is the general knowledge, that black people owned slaves, that we would have some contradictory feelings about that. Or better put, that one would not feel good about that. It's very, very hard for me to think of slavery as a benign, as a decent, as a wonderful system, no matter how it is constructed. And, as an anthropologist I went through my phase of cultural relativism. I'm done with that. I have no difficulty in saying that I think there are some, what I would want to describe as universal . . . not universally held values, but values that I wish could be held universally, and one of these is the total opposition to slavery. And, so to feel that my great-grandmother had acquired the kind of wealth and the kind of prestige that would allow her to own slaves, I balance that with, 'she owned slaves!' On the other hand, here was a woman of just extraordinary intelligence, ability. |

In assessing the complex and conflicting identities of Anna Kingsley and feelings expressed by Kingsley descendants with respect to their own relationship to Anna, I also see the contradictions and strength that was Anna Kingsley's life. I imagine that Anna Kingsley was determined to survive and she did. Anna, who was purchased in 1806 at the age of 13 by Zephaniah Kingsley Jr., learned to understand power and how it operated at a young age. She must have consciously used her multiple identities — her knowledge, her beauty, and her position as mistress — to secure a future for herself and her children. She lived and survived in her own way, far from her West African birthplace of Senegal, leaving precious treasures, children, and grandchildren, who have gone on to navigate their own issues of culture, heritage, and identity as Africans in America within and outside plantation landscapes.

Conclusion

The Kingsley Plantation holds a combination of the plantation as a physical place in the form of tangible and interactively accessible reminders of slavery (i.e., plantation grave sites, slave housing remains, abandoned fields, waterways) and a socially constructed space of intersecting identities, heritage, and celebration. This combination of preserved physical place and valued memory and meaning keeps it relevant and makes it a significant site of knowledge about ways of looking at the past for those who continue to visit the grounds today.

The Kingsley Plantation community provides an opportunity to study and dialogue about the legacy of plantations and other segregated spaces in America. By addressing complexities of identity formation and experiences of place in connecting the past and the present, this interpretation gives primacy to the notion of looking back in order to learn how to move forward—a theme underscored by Dr. Cole in her 2009 talk at the Kingsley Heritage Celebration.

About the Author

Antoinette T. Jackson is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of South Florida.

Notes

1. This research was conducted under National Park Service (NPS) Contract No. Q5038000491 "Ethnohistorical Study of Kingsley Plantation Community," Allan F. Burns (University of Florida) and Antoinette Jackson (University of Florida), Co-Principal Investigators. Participant observation and key informant interviews for the purpose of collecting oral history were the primary means of obtaining ethnographic field data about the Kingsley Plantation community. Interviews were conducted primarily with persons of African descent ranging from 20 to 86 years old in greater Jacksonville, Amelia Island, and St. Augustine, Florida. Additionally, oral history and interview testimony provided by Zephaniah Kingsley's African, European, and Latino descendant family members have been incorporated in this analysis.

Acknowledgement and thank you to the following for their interest in and support of this project: Marsha Dean Phelts for research leads and her wealth of knowledge on the history of Jacksonville's African American community; Barbara Goodman, Superintendent of Fort Caroline National Memorial and Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve; John Whitehurst, Cultural Resource Manager, Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve; Paul Ghioto, Timucuan Preserve; Charles Tingley, Library Manager, and G. Leslie Wilson, Assistant Library Manager, at the St. Augustine Historical Society; Eileen Brady, Librarian, Special Collections Department, University of North Florida Library, Eartha M. M. White Collection; Kay Tullis, Jacksonville Historical Society; Glenn Emery, Senior Librarian Florida Collection, Jacksonville Public Library; and Yolanda N. Jackson, Nevada Graphics. Finally and most importantly, I would like to extend a very special acknowledgement to those persons who agreed to be interviewed and/or videotaped for the Kingsley Plantation project in 1998 and 2001: Marion Christopher Alston, MaVynee Betsch, Peri Frances Betsch, Mildred Christopher Johnson, Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole, James Daniels, Dr. Kathleen Deagan, Harriet Gibbs Gardiner, William Tucker Gibbs, Becky Gibbs, Emily Gibbs, George W. Gibbs, Adewale Kule-Mele (Anthony Scott); Theresa Scott, Manuel Lebron, John Murrell, Mildred Murrell, Evette Murrell, Marsha Dean Phelts, Camilla Thompson, Walter Whetstone, and Ike (Isiah) Williams.

2. See: Carita Doggett Corse, The Key to the Golden Islands (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1931); Faye L. Glover, Zephaniah Kingsley: Nonconformist, Slave Trader, Patriarch (Masters Thesis, Atlanta University, Atlanta, Georgia, 1970); Philip S. May, "Zephaniah Kingsley, Nonconformist (1765-1843)," The Florida Historical Quarterly 23(3)(1045): 145-159; Daniel L Schafer, "Shades of Freedom: Anna Kingsley in Senegal, Florida, and Haiti." Slavery and Abolition 17(1)(1996): 130-154; Jean B. Stephens, "Zephaniah Kingsley and the Recaptured Africans," El Escribino 15 (1978): 71-76.

3. Schafer, "Shades of Freedom."

4. Marsha Dean Phelts, American Beach for African Americans (Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press, 1997).

5. Interview with Antoinette T. Jackson, Amelia Island, Florida, 25 August, 2001.

6. Ibid.

7. Phelts, 1997.

8. Interview with Antoinette T. Jackson, Atlanta, Georgia, October 3, 2001.

9. MaVynee Lewis Betsch, Amelia Island, Florida, participated in videotaped interviews conducted by University of Florida graduate Students (Antonio de la Peña, Rachel Sandals, Edward Shaw, and Greg De Vries) at the Kingsley Heritage Festival and Family Reunion on Fort George, Island, October 10-11, 1998. Thanks to the tireless efforts of MaVynee Betsch, who died in 2005, and the generosity of the Amelia Island Plantation Company, the National Park Service has been given an 8.5-acre pristine sand dune called NaNa at the center of the community. That land is now part of the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve. http://www.nps.gov/timu/historyculture/ambch.htm

10. The following people participated in videotaped interviews conducted by University of Florida graduate students (Antonio de la Peña, Rachel Sandals, Edward Shaw, and Greg De Vries) at the Kingsley Heritage Festival and Family Reunion on Fort George, Island, October 10-11, 1998: Adewale Kule-mele, Jacksonville, Florida; George Gibbs, St. Augustine, Florida; Harriet Gibbs Gardiner, Jacksonville, Florida; William Tucker Gibbs, Miami, Florida; Emilie Gibbs, Miami, Florida; Becky Gibbs, Miami, Florida; Denny Gibbs, Miami, Florida; Sandra Lebron and Manuel Lebron, Dominican Republic; Marion Christopher Alston, Jacksonville, Florida; Elizabeth Kingsley Hull, McLean, Virginia; Steve McQueen Smith, Columbia, South Carolina; and MaVynee Lewis Betsch, Amelia Island, Florida. Their videotaped stories are on file at the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserves headquarters in Jacksonville, Florida.

11. Daniel L. Schafer, "Zepahniah Kingsley's Laurel Grove Plantation, 1803-1813," in Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida, ed. Jane G. Landers (Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press, 2000), 98-120.

12. Interview with Antoinette T. Jackson, Atlanta, Georgia, October 2, 2001.