Exhibit Review

Temple of Invention: History of a National Landmark

Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture, Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC

July 1, 2006-January 21, 2008

Temple of Invention: History of a National Landmark, on exhibit in the renovated Smithsonian American Art Museum and National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, is a loving portrait of the building, once the home of the U.S. Patent Office, and its long history in the nation's capital. Tucked away in a second floor space that is both intimate and open, this jewel of an exhibit explores the evolution of the building and its place in the city through daguerreotypes, prints, models, and letters pulled from the collections of the museum, the gallery, the Library of Congress, and the National Archives. Due to the fragility of the originals, many of the items on display are reproductions, which do not in any way detract from the impact of the content. The physical installation is complemented by an online exhibit that uses the best Web techniques, allowing visitors to zoom in on portraits, expand interpretive text, and revisit the exhibit multiple times.(1) Though the online exhibit can stand on its own, the physical installation of the exhibit is worth the trip.

The title of the exhibit, Temple of Invention, alludes to the building's classic Greek revival style and the technical ingenuity inherent in the patent process. Begun in 1836 to house the Federal Government's growing patent office, the building consists of four wings with central halls for the collection and display of innovative machines and other patentable items. The exhibit uses images of two of the building's architects to provide insight into the human hands that shaped the structure. Robert Mills, architect of the south and east wings, poses formally with his wife, gazing directly at the viewer with a slight sparkle in his eye. Mills created glass cabinets to showcase the patent models—the best ideas of the growing nation—and designed the vaulted exhibition hall on the top floor. Thomas U. Walter, designer of the U.S. Capitol dome, replaced Mills on the project and oversaw construction of the north and west wings. His portrait shows a steely gaze, captivating the viewer and compelling contemplation of the vast contributions he made to the city.

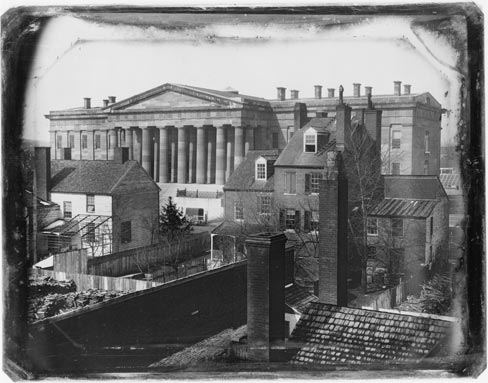

|

This daguerreotype of the Patent Office Building in Washington, DC, produced by John Plumbe in 1846, is the earliest known photograph of the building. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

In addition to patent models and drawings, the building housed historic artifacts such as the original Declaration of Independence and Benjamin Franklin's printing press. It became known as the "Museum of Models" and the "Museum of Curiosities" and attracted more than 100,000 visitors annually.

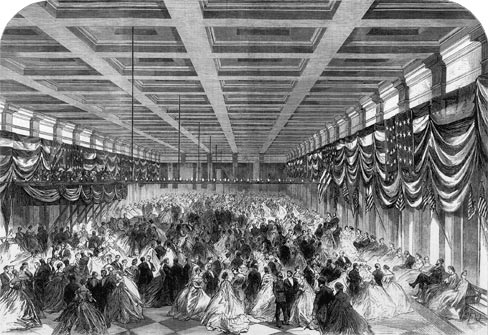

Portraits and archival materials illustrate the role the building played in the Civil War. Engravings show revelers filling the third floor for President Abraham Lincoln's second inaugural ball in 1865. First-person accounts describe the buffet and the rush of people to partake in the festivities. More evocative of the times are the Matthew Brady photographic portraits of President Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln, each with an expression that foreshadows the troubles that are to come to them and to the nation.

The Patent Office building also has a connection with other famous Americans of the Civil War era. Clara Barton became a confidential clerk to the patent commissioner in 1854. She was the first woman to serve in a permanent position in the Federal Government and to be paid the same wages as a man. Accompanying an engraving of her showing a strong, set jaw are quotations revealing her resilient spirit in the face of many insults from her male coworkers. When the Patent Office became a military hospital in 1861, Barton treated wounded soldiers there (she founded the American Red Cross 20 years later). Walt Whitman, seen in the exhibit in the quintessential image of his later years, gazing off thoughtfully into the distance, also worked in the war hospital.

In 1877, a huge conflagration nearly destroyed the Patent Office. Started by sparks from a chimney flue, the fire spread quickly, much to the surprise of witnesses who thought that the Walter-designed wings were of fireproof construction. The office's large amount of flammable materials—basically, the patent drawings and models—fed the flames, and water pressure proved too weak to reach the roof. The fire gutted the model halls in the north and west wings. Engravings of the fire and photographs of the aftermath tell the tragic story. Although employees carried significant quantities of materials to safety, thousands of patent models were lost.

|

This early 20th-century photograph shows the west model hall as redesigned after the 1877 fire had gutted the building. (Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.) |

Rebuilding began almost immediately under the direction of Adolf Cluss, a prolific Washington architect. Completed in a "modern Renaissance" style, the west model hall featured fireproof iron cases and encaustic tiles. Recently renovated, the hall now houses the Luce Foundation Center for American Art, an open storage and study center for portions of the Smithsonian American Art Museum collections.

The Patent Office building's fortunes fell and rose again in the 20th century. A hand-colored postcard dating from 1929 depicts the Patent Office as a major tourist attraction worthy of writing home about. But by 1932, the Patent Office moved out, the Civil Service Commission moved in, and the public no longer visited the building to see patent models in glass cases. A 1939 political cartoon shows former President Theodore Roosevelt, a champion of civil service reforms, watching over the commission's headquarters. In 1953, the building was slated for demolition for a parking garage. Saved from this fate by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the building was transferred to the Smithsonian in 1958 to house the institution's growing collections of American art and portraiture. A photograph of President Lyndon B. Johnson speaking at the opening ceremonies of the newly renovated museums in 1968 evokes the building's return to grandeur.

The collections of both the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery trebled in the intervening three decades, and in 2000 the museums closed to begin a six-year restoration and renovation. A model showing the new canopy recently completed over the interior courtyard represents the current chapter of the building's history. Designed by Sir Norman Foster, the glass and steel construction floats over the courtyard, connecting the past and the future in a building whose hallmark has been inspiration and invention. This chapter hints at the life to come in this landmark building.

The final part of the exhibit—not to be missed—awaits beyond a pair of French doors in the room. The doors open onto a small balcony with a café, and it takes just a few steps for a vista of 8th Street to unfold. Framed by the classical columns is the venerable edifice of the National Archives building in visual conversation with the Patent Office. Among these stone giants, visitors can sip a coffee and drink in the changes in the city that surround the building. Percolating through one's mind is the sense that the Patent Office has undergone many changes of use and structure yet remains an enduring sentinel of human ingenuity.

Christine Henry

Institute of Museum and Library Services

Note

1. The exhibit is available online at http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/pob/, accessed on December 2, 2007.