Article

Preparing for a National Celebration of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial

by Sandy Brue

I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. —President Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864 (1) |

The United States is approaching two significant anniversaries in the nation's history: the bicentennial, in 2009, of the birth of former President Abraham Lincoln, and, in 2011, the sesquicentennial of the Civil War. These intertwined events bind the fabric of the U.S.'s national story, reconnect people to their frontier roots, remind them of a time when the nation was torn apart, and expose the evils of slavery and the challenges of race relations. As the 16th president of the United States, Lincoln, a complex man from humble beginnings, inherited the deeply rooted social, political, and economic contradiction of slavery passed over by the founding fathers.

Part of the British North American experience for 150 years by the time of the American Revolution, slavery was inherited by each successive generation until Lincoln, unwilling to compromise the issue further, confronted it.(2) Now, 200 years after Lincoln's birth, the issues of his personal and political life are still relevant. When the two-year commemoration closes in 2010, a multi-year Civil War national memorial period will open. These two epochal periods offer a forum for the observance of America's greatest national crisis. These tandem events remind us that Lincoln's solutions to the nation's still unresolved race relations problems were forever lost to an assassin's bullet.

In 2000, the United States Congress appointed a 15-member Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission to increase national and international knowledge of Lincoln, pay tribute to his accomplishments, and highlight his influence on the nation's development.(3) Co-chairs Senator Richard J. Durbin, Congressman Ray LaHood, and Abraham Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer were chosen as leaders for their knowledge and contributions to the study of the nation's 16th president. Other commission members are collectors of Abraham Lincolniana, scholars, educators, authors, and government officials. Other active organizations include the Lincoln States Bicentennial Task Force, a National Park Service work group, and local, state, and county commissions. The Organization of American Historians, the Journal of American History, universities, Lincoln museums, and other associations and groups are working together on educational programming and community outreach for the commemoration period. Other plans and projects address the preservation of Lincoln-era artifacts, traveling exhibits, signature celebrations, statues and coins, and other memorabilia.

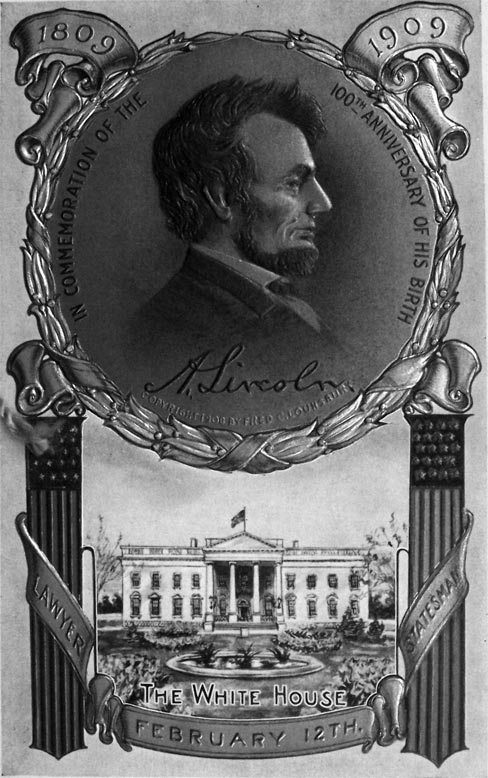

These collaborations, many of which include the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site in Hodgenville, Kentucky, promote the shared goals of strengthening the foundations of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity, and encouraging public participation and scholarship on Lincoln and his legacy. The two-year celebration opens on the steps of the Memorial Building at the park on February 12, 2008.(Figure 1) A year of national signature events culminates with the rededication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, in 2009, the year of Lincoln's 200th birthday.

|

Figure 1. The Memorial Building at the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site in Kentucky marks the site of former President Lincoln's birth. (Courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

The Lincoln Centennial

Preparations at Abraham Lincoln Birthplace include restoration of the Memorial Building, rehabilitation of the surrounding landscape and visitor center, and the installation of new interior exhibits and outdoor wayside interpretive panels. The complexity of these preservation projects is best understood through a historical review of the Memorial Building construction project and the preparations for the centennial of Lincoln's birth in 1909.

The Sinking Spring Farm, a 300-acre tract of land bought by Abraham Lincoln's parents, Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, for $200 in 1808, was sold, apportioned, and resold many times after the young family had left Kentucky to settle in Indiana. The property sale in 1905 attracted investor interest nationwide through articles published in the Louisville Courier-Journal and other newspapers. On August 28, 1905, Richard Lloyd Jones bought the farm in the name of Robert J. Collier, editor of Collier's Weekly, to be held "in trust for the nation."(4) Incorporated on April 18, 1906, the Lincoln Farm Association planned to develop a memorial to Abraham Lincoln in time for the 100th anniversary of his birth.(5) The association's board of directors included the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens; political leaders Henry Watterson, William Jennings Bryan, and William H. Taft; journalists and editors Ida Tarbell, Samuel L. Clemens, and Albert Shaw; and other well-known figures. Robert Collier, also on the Board of Directors, used his magazine to promote the newly formed Lincoln Farm Association and encouraged contributions for a national Lincoln memorial on the site where the nation's 16th president was born. President Theodore Roosevelt, himself devoted to preserving Lincoln's memory, passionately endorsed the project.

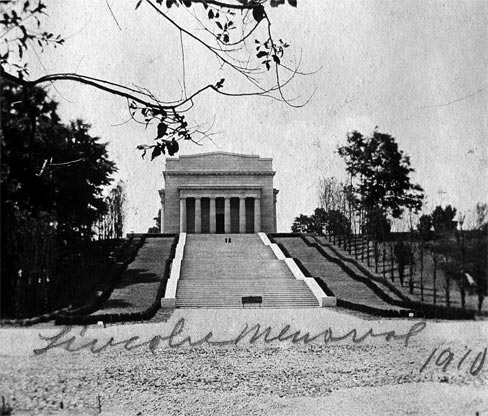

Designed and built between 1906 and 1910—the time during which the United States ended its isolationist policies and became a world power—the Memorial Building is a fitting monument to one of the nation's heroes. The country, rapidly growing both economically and socially, needed strong, powerful role models whose personal traits were equal to the task of nation building, both at home and abroad.(6) President Roosevelt dedicated the building's cornerstone in 1909 only a month before the end of his second term. Roosevelt, who had always championed Lincoln as his hero, believed the values of the common man and progressive policies had eclipsed the power of the political machines—a sentiment Lincoln would have admired.

The Lincoln Farm Association selected the architect John Russell Pope to design a memorial to house the birthplace cabin. Pope, fresh from his studies of classical architecture in Europe, designed a building befitting a Roman emperor. The architect envisioned a two-story museum with an avenue of trees leading to the entrance and a central court featuring a copy of Saint-Gaudens's "Standing Lincoln" statue from Chicago's Lincoln Park. The Lincoln Farm Association approved Pope's design clearly intending for the birthplace to be the country's principal monument to the former president.

Driving Pope's design was the association's desire to return the Lincoln birth cabin to the very site on the knoll where it had supposedly originally stood.(7) Shortly after the Lincoln Farm Association had acquired the Sinking Spring Farm, they bought what people thought were the "original birthplace cabin" logs for $1,000. These logs had traveled on exhibit across the country and sat in storage at College Point on Long Island, New York, until the association acquired them.

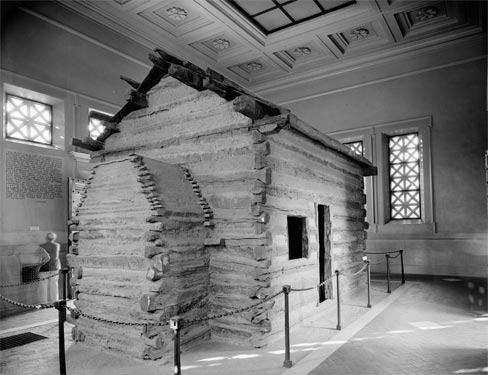

Unfortunately, funds fell short of the anticipated goal, and Pope had to simplify his plans. He placed the Memorial Building on the knoll above the Sinking Spring and took advantage of the incline to create a dramatic and symbolic approach. The design as realized features four sets of granite stairs that ascend the terraced hill. Nearly 37 feet wide at the base, the 56 stairs—one for each year of Lincoln's life—narrow to 30 feet at the summit. A low hedge enclosed terraced panels on each side of the steps, and Lombardy poplars framed the building.(8) Beyond the one-story Doric portico, two bronze-panel doors open to the cabin with matching double doors at the north entrance.(Figure 2) A set of 16 rosettes crown the ceiling around a raised skylight and 16 stanchions encircle the cabin, symbolic of Lincoln's service as the nation's 16th president.

|

Figure 2. The symbolic cabin inside the Memorial Building reminds visitors of Abraham Lincoln's humble origins. (Courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

A cold rain fell on the centennial celebration day in 1909, but neither the weather nor the unfinished memorial deterred President Roosevelt who, with his party, slogged up the rain-soaked hill to deliver a roaring tribute to his hero on the spot where Lincoln was born. The celebration reverberated across the country. Speeches, formal dinners, and fireworks marked the celebration from New York to San Francisco, along with booklets containing Lincoln's most famous speeches, centennial coins, ribbons, and medals proudly worn at county, state, and national events.(Figure 3) Whereas President Roosevelt spoke about Lincoln at Hodgenville, his vice president, Charles Fairbanks, delivered a speech in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. In Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln's place of residence from 1837 until his move to the White House in 1861, Lincoln and Mary Ann Todd's first son, Robert, listened to speeches by William Jennings Bryan and the British and French Ambassadors.

The completion of the Memorial Building in 1910 provided another opportunity for celebration, which again brought the nation's president to Kentucky. President William Howard Taft traveled to Hodgenville in late 1911 and addressed thousands of people on the steps of the new memorial.

In 1911, the Lincoln Farm Association, its task complete, turned the park over to the State of Kentucky. In 1912, the first bills appeared in Congress to convey the park to the Federal Government. It was not until 1916, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill into law, that the Sinking Spring Farm became federal property. Wilson traveled to the park in September of that year to deliver an address, "Lincoln's Beginnings," on the acceptance of the deed of gift of the Lincoln farm to the nation, making his the third visit to Lincoln's place of birth by a sitting U.S. president.(9) The War Department administered the site, appointing Richard Lloyd Jones as commissioner during the early years. Congress transferred the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace from the War Department to the Department of the Interior in 1933.(10)

Over the years, people questioned the authenticity of the logs bought by the Lincoln Farm Association and now enshrined in the Memorial Building. Scholarly research into the cabin did not begin until 1949, when Roy Hays published an article in The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly titled, "Is the Lincoln Birthplace Cabin Authentic?"(11) In 2004, a dendrochronologist using core samples dated the oldest log used to build the cabin within the Memorial Building to 1848, thus establishing that the cabin could not have been the original birthplace cabin. Although not the original, the cabin is nonetheless significant for its role in perpetuating the image of Lincoln's dramatic rise from humble beginnings to the White House. Today, the park refers to the cabin as the "symbolic cabin."(12)

Preparing the Park for the Lincoln Bicentennial

The National Park Service began preparing for the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial in 2002 and developed an action plan in August 2006.(13) The Lincoln Birthplace and other Lincoln-related national parks anticipate significant interest and attention during the bicentennial period.(14) As steward of these sites, the National Park Service has a continuing responsibility to protect them, communicate their significance, and coordinate with the commissions and organizations working on the bicentennial observance.

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace began preparing for the bicentennial in 1999 with the development of a long-range interpretive plan that laid the foundation for programming, media needs, and exhibit and wayside development. The goal of the plan is to "commemorate the birth and early life of Abraham Lincoln and interpret the relationship of his background and frontier environment to his service for his country as president of the United States during the crucial years of the Civil War."(15) The challenge for Lincoln Birthplace is how the park can effectively convey the significance of Lincoln's first seven years living in Kentucky and how those years shaped the fundamental character he needed to lead the nation successfully though the trials of the Civil War.

Complicating this challenge is the formal memorial setting carved from the original farmstead by the Lincoln Farm Association. Few records of the original farm survive that document the period between the Lincoln family's departure in 1811 and the purchase of the farm by the Lincoln Farm Association in 1905. Furthermore, few traces of the farmstead itself survive from the Lincoln family days.

The two notable exceptions are the Sinking Spring and the Boundary Oak. The Lincoln family's primary source of water, the spring, also known as Rock Spring and Cave Spring, which appears in an 1802 farm survey, is an example of karst topography prevalent in this part of Kentucky. The Boundary Oak, a large white oak, likewise appears on early surveys. The construction of the Memorial Building and the development of the site into a park by the Federal Government after 1916 erased all other vestiges of the site's agricultural past.(16)

Until it died in 1976, the Boundary Oak was the "last living link" to Abraham Lincoln. This white oak served as a corner or boundary tree since the 1802 survey. It was 6 feet in diameter and approximately 90 feet in height. Its branches spread 115 feet. The tree, thought to be between 25 and 30 years old at Lincoln's birth, was located less than 150 yards from the cabin where he was born. Today, the site is marked with one of the newly designed wayside markers. A large slab of the white oak is on permanent exhibit in the visitor center.

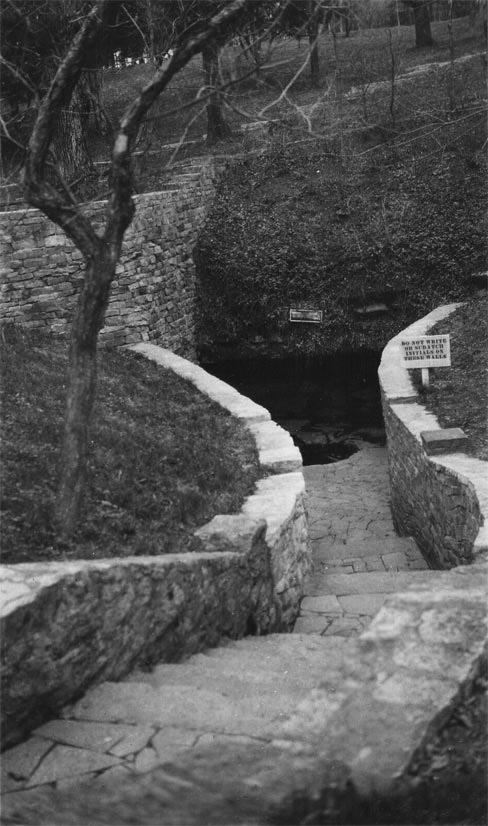

The spring, located just west of the Memorial Building steps, is an excellent example of a karst window, a special type of sinkhole typical of Kentucky's karst topography and hydrologic systems. The water, flowing year-round, drains through the subsurface and empties into a branch of the Nolin River a short distance from the park. The earliest surviving photograph taken in 1884 shows the spring thickly covered with vegetation.(Figure 4) This site will have a new wayside marker that will illustrate karst topography, explain the importance of this water source for the Lincoln family, and include late 19th-century photos.

|

Figure 4. This circa 1884 photograph of the Sinking Spring is the earliest known image of the spring on the farm where Abraham Lincoln was born. (Courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

Construction of the Memorial Building directly above Sinking Spring created significant access problems for visitors and left a legacy of interpretive challenges for park staff. Annual flooding deposited several feet of water, mud, and slime at the foot of the memorial steps. During its administration of the site, the War Department made extensive changes to the spring to facilitate visitation, constructing stone retaining walls and steps to provide a safe way down to the spring.(Figure 5) Unfortunately, the spring's natural setting disappeared in the process, replaced by an artificial setting of steps and walls that make it difficult for park interpreters to connect Lincoln to his rural Kentucky roots. Visitors are immediately struck by the formal memorial setting, and only after ascending the 56 steps of the Memorial Building are they introduced to the one-room rustic cabin—a token of the harsh frontier life as the Lincoln family knew it—preserved in a classical revival shrine.

|

Figure 5. The U.S. War Department built the steps and retaining walls shown in this 1934 photograph to facilitate public access to the Sinking Spring. (Courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

Recognizing the challenge of interpreting Lincoln's frontier life and how it influenced his later policies and politics, the park embarked upon major visitor center and exhibit upgrades in anticipation of the bicentennial. The park's new exhibits interpret the birth and early years of Lincoln's life, the Lincoln Farm Association, and the Centennial, and they provide an orientation to the park.(17)

Completed in 1959 as part of the National Park Service's Mission 66 modernization program, the visitor center is the public's first point of contact with the park. Entering the freshly painted and re-carpeted building, visitors now encounter life size figures representing the Lincoln family when Abraham Lincoln was about one year old. Figures of his father, Thomas, his mother, Nancy Hanks, holding the young Lincoln, and his sister, Sarah, about three years old, are present, their hands and faces sculpted in clay and their resin-coated fiberglass and foam frames clad in carefully chosen period clothing. Behind the figures and slightly to the right is the Lincoln quote, "I happen temporarily to occupy this big White House. I am a living witness that any one of your children may look to come here as my father's child has."(18) The effect is stunning.

In the redesigned visitor center lobby, a new environmentally controlled exhibit case houses the Lincoln family Bible within view of the front desk. This Bible, which belonged to Abraham Lincoln's parents, is the only artifact in the park collection directly associated with the Lincoln family. Below the 1807 birth entry for his sister, Sarah, are the words, "Abraham Lincoln. Son of Thos & Nancy Lincoln was born February 12, 1809," in Lincoln's own handwriting.(19)

Passing the Lincoln Bible, visitors enter a hallway leading to a full-size cabin exhibit built according to the dimensions of cabins constructed in Kentucky during the early 19th century.(Figure 6) A fieldstone fireplace with mantel, cooking utensils, herbs hanging from the ceiling, red-ware plates, bowls, cow horn cups, candle molds, hand-made soap, a water bucket, dipper, wash tub, and other items provide the interpretive staff opportunities for Kentucky frontier life educational programming.

The cabin exhibit features a pole bed based on Dennis Friend Hanks's recollection of his cousin Abraham's birth. Dennis remembered that Nancy was lying in a pole bed looking happy on the day Abraham was born. Tom had built up a good fire and thrown a bear skin over them to keep them warm.(20) Period reproduction clothing hangs from pegs along the wall. A bearskin covers the bed, and a Kentucky long rifle and powder horn hang on the wall. A cross-buck table and bench sit in the center of the room. Since the only documentation relating to the cabin is the quote about the bed, the furnishings chosen for the cabin are period appropriate or typical of what one would find in a cabin in the early 19th century.

Beyond the cabin exhibit, visitors encounter a family genealogy exhibit that traces the lineage of both parents and old photos of the cabin and Boundary Oak. On the opposite side is a large glass window framing a view of the Memorial Building.

According to a historic structure report completed in 2001, the nearly 100-year-old Memorial Building is in good condition.(21) The report outlines the efforts over the years to control the interior environment and their impacts on the overall visitor experience. The report recommends restoring the building to the 1909-1911 historic period.

In September 2004, the National Park Service contracted with an Atlanta architectural firm to determine the cause of mold, peeling paint, and suspected moisture infiltration from the exterior. The park followed up with an engineering assessment in the spring of 2005 and a preservation plan for cleaning and re-pointing the stone exterior, rehabilitating the original metal scuppers and downspouts, replacing the roof, and installing a new granite accessibility ramp. The building was now tightly protected from moisture intrusion; the interior work, however, proved to be a much larger project.

The Memorial Building's historic structure report recommends removing a wooden frame drop ceiling installed in 1959 and restoring the original skylight. It also recommends restoring plaster on the interior walls and redirecting airflow from the HVAC floor-mounted supply grille away from the cabin to provide more even circulation. These corrective measures will cost more than $1 million and require detailed compliance.(22) Since the extensive planning, design, and contractual work required could not be done before the 2008 kick-off event, a smaller cleaning and repainting project will give the building a temporary facelift until the more extensive work begins in 2009.

Pope's original landscaping plan for the Memorial Building created terraces to complement the slope and location of the steps. Formal hedges of two different heights defined the grass panels and the Memorial Plaza. Lombardy poplars, common in classical landscapes, bordered the stairway.(Figure 7) In November 1935, these poplars, subject to disease and having a lifespan of approximately 30 years, gave way to evergreens. A 2004 cultural landscape report noted that the vegetation around the Memorial Building had lost its shape and compromised the formal design of the site.

|

Figure 7. Architect John Russell Pope's original landscape plan included rows of Lombardy poplars flanking the steps leading to the Memorial Building. (Courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

Based on the cultural landscape report recommendations, the park replaced the split rail fencing surrounding the entire site beginning in the fall of 2006. It also planted new redbud and dogwood trees along the stretch of U.S. highway 31E that divides the 116 acres of the park in two, with the visitor center and Memorial Building on one side of the road and a large picnic area with hiking trails on the other. The dogwoods, subject to blight, were replaced with serviceberry trees as the blooms are similar and expected to produce the same effect.

The Bicentennial Celebratory Event

The Southeast Regional Bicentennial Planning Team, which includes representatives from the National Park Service and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission, met on April 13, 2005, to begin planning for the park's February 12, 2008, bicentennial kick-off signature event. The park anticipates national and international attention and upwards of one million visitors over the course of the four-day celebration.

Preparing the park's infrastructure for the bicentennial is one aspect of the celebration; planning for the actual event and its legacy is another. The park has hired an education specialist to coordinate programming for state and local schools. An ongoing bicentennial speaker series, launched in the spring of 2005, is bringing renowned authors, scholars, and educators to Hodgenville, Kentucky. Michael Chesson spoke on the Civil War in Kentucky. Author and educator Margaret Wolfe gave a presentation on frontier southern women. Noted author Catherine Clinton presented her research on Harriet Tubman. Recently, Thomas Mackey presented a paper entitled, "They Belong to the Ages: The Enduring Values of Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr.," in honor of King.

In the fall of 2006 and 2007, the park hosted "Walk through Lincoln's Life," an event for K-6 students. Re-enactors, demonstrators, musicians, and rail-splitters helped transport 1,500 children and teachers back to the early 19th century to encounter life as the Lincolns might have experienced it. In late June 2007, the park hosted a "Parks as Classrooms" grant-funded workshop for teachers and staff of Lincoln-related sites in Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois. Teachers designed online lesson plans with pre-visit, post-visit, and long-distance learning options. They had the opportunity to interact with staff from the various Lincoln sites to determine what works best in the classroom and to design effective curriculum-based programs that will engage students in learning about history, math, science, and social studies. This workshop was hosted by the Kentucky Historical Society and featured Frank J. Williams, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Rhode Island, and founding chairman of the Lincoln Forum, as keynote speaker.

The Kentucky Historical Society began hosting statewide Lincoln commemorative events in June 2006 with the recreation of the Lincoln and Hanks wedding to celebrate Lincoln's parents' 200th wedding anniversary. The Kentucky Department of Transportation has erected welcome signs along the interstate highways that read, "The Birthplace of Abraham Lincoln," and a bicentennial license plate is now available.

Kentucky has also created a unique logo for the bicentennial featuring the log cabin motif. This logo appears on the state's website, stationery, and promotional materials. There will be commissioned artwork and three new Lincoln statues, including a seated Lincoln overlooking the Ohio River in downtown Louisville by Ed Hamilton, the sculptor who also produced other noted figures in this waterfront park. A statue portraying Lincoln as a young boy is underway for Hodgenville's town square. The Hodgenville boy statue will complement the Adolph A. Weinman adult statue of Lincoln placed on the square in 1909 to honor the centennial of Lincoln's birth. A third statue will go up in Springfield, Kentucky, where Thomas Lincoln, the president's father, grew up.

The anticipated interest in Abraham Lincoln sites located within eight rural Kentucky counties helped them qualify for a three-year grant to promote heritage tourism sponsored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Preservation Kentucky, and the Kentucky Heritage Council and funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. As a member of this group's steering committee, Abraham Lincoln Birthplace has offered interpretive workshops and site assessments to assist statewide planning efforts.

The city of Hodgenville has devoted much time and energy to prepare for the influx of visitors and continuously updates the information about events on its website.(23) The cities of Elizabethtown and Bardstown meet regularly with the mayor and city council of Hodgenville to review logistics. A history symposium will take place on the afternoon of February 11 with Pulitzer Prize winning author Doris Kearns Goodwin as the featured speaker. The evening gala event on February 11 will include performances by the Louisville Orchestra and the Kentucky Opera. The orchestra will debut a new symphony commissioned by internationally recognized composer and musician Peter Schickele. Soprano Angela Brown and the Kentucky Opera will perform two spirituals and two prayers from Margaret Garner, an American opera based on the pre-Civil War story of a fugitive slave who sacrificed her child rather than see that child returned to a life of slavery.(24)

Regional leaders hope that these celebrations offer a positive lasting impression for visitors to the area. With CNN, C-SPAN, the History Channel, and other major networks planning to cover these activities, there is every opportunity for all Americans and international visitors to experience the legacy of Abraham Lincoln and his Kentucky roots.

About the Author

Sandy Brue is the chief of interpretation and resource management at Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site in Hodgenville, Kentucky.

Notes

1. Charles W. Moores, Lincoln Addresses and Letters (New York, NY: American Book Company, 1914), 204-6.

2. James Oliver Horton, "Slavery in American History: An Uncomfortable National Dialogue," in Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory, eds. James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton (New York, NY: The New Press, 2006), 38.

3. The Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission maintains a website at http://www.abrahamlincoln200.org/, accessed on August 23, 2007.

4. Collier's Weekly, February 10, 1906, 12-15.

5. Kent Masterson Brown, "Report on the Title of Thomas Lincoln To, and the History of, The Lincoln Boyhood Home Along Knob Creek in LaRue County, Kentucky," unpublished manuscript. According to Hardin County, Kentucky Circuit Court Records, Richard Mather, a land speculator from New York sold David Vance 300 acres of what was then called the Sinking Spring Farm, May 1, 1805. Vance, who never fully paid for the land, sold it to Isaac Bush November 2, 1805. Thomas and Nancy Lincoln purchased the Sinking Spring Farm from Isaac Bush on December 12, 1808. These agreements were not recorded and payment was never made in full to Richard Mather therefore the farm remained on tax assessment records of Hardin County under the name of Mather.

Abraham Lincoln was born to Thomas and Nancy Lincoln in a cabin above the Sinking Spring on February 12, 1809. The couple with young Abraham and daughter Sarah lived on the farm until they were evicted in the dispute over ownership. Thomas Lincoln filed a counter claim against Richard Mather but the court decided against him and the land was sold at public auction. While the Lincoln's were suing to reclaim their farm they rented 30 acres along Knob Creek from George Lindsey. The Knob Creek farm was located along the west side of the Bardstown and Green River Turnpike about eight miles from the Sinking Spring Farm.

6. Dwight T. Pitcaithley, "Abraham Lincoln's Birthplace Cabin: The Making of an American Icon," in Myth, Memory, and the Making of the American Landscape, ed. Paul A. Shackel (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001), 240-1.

7. Gloria Peterson, An Administrative History of Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site, Hodgenville, Kentucky (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1968), 21-3.

8. Robert W. Blythe, Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site Historic Resource Study (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2001), 32-35; Abraham Lincoln Birthplace Memorial Building Historic Structure Report (Atlanta, GA: National Park Service Southeast Regional Office, 2001).

9. The full text of President Wilson's address is available online from the American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=65394, accessed on August 23, 2007.

10. Peterson, 33.

11. Roy Hays, "Is the Lincoln Birthplace Cabin Authentic?" The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly 5 no. 3 (September 1948): 127-63.

12. Tri-Park Handbook, published by Eastern National (in production at the time of publication).

13. Bicentennial of the Birth of Abraham Lincoln: An Action Plan for the Midwest Region (Omaha, NE: National Park Service Midwest Regional Office, 2006).

14. The list of Lincoln-related sites in the National Park System is extensive. It includes memorials, sites directly associated with Lincoln, and Civil War battlefields and other sites that interpret historical events in which the 16th president played a part. The service's primary Lincoln sites are Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park in Hodgenville, Kentucky; Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial in Lincoln City, Indiana; Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, Illinois; and Ford's Theatre National Historic Site and the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC. The secondary sites are Mount Rushmore National Memorial, Keystone, South Dakota; Antietam National Battlefield, Sharpsburg, Maryland; Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, Cornish, New Hampshire; Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site, Flat Rock, North Carolina; and Lincoln and President's Parks, Washington, DC. The National Park System also includes more than 40 Civil War era sites.

15. Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site (Harpers Ferry, WV: National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center, 1999).

16. Lucy Lawliss and Susan Hitchcock, Cultural Landscape Report (Atlanta, GA: National Park Service Southeast Regional Office, 2004).

17. The park worked with exhibit design experts at the National Park Service's Harpers Ferry Center in West Virginia.

18. Abraham Lincoln, address to "One Hundred Sixty-sixth Ohio Regiment on August 22, 1964."

19. The Lincoln Family Bible was in the possession of the Johnson family, stepchildren of Thomas Lincoln, until 1893, when it was purchased for exhibition at the Chicago World's Fair. The Federal Government bought the Bible in 1926 and transferred it to Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site in 1959. The Chicago Historical Society preserves a few original pages with Abraham Lincoln's handwriting.

20. Louis A. Warren, Lincoln's Parentage and Childhood: A History of the Kentucky Lincolns Supported by Documentary Evidence (New York, NY: The Century Company, 1926), 104.

21. Abraham Lincoln Birthplace Memorial Building, Historic Structure Report (Atlanta, GA: National Park Service Southeast Regional Office, 2001).

22. The National Park Service's Denver Service Center will manage the project.

23. "Hodgenville, Kentucky," http://hodgenville.info/, accessed on August 23, 2007.

24. Visit "Margaret Garner: A New American Opera" for more information: http://www.margaretgarner.org/, accessed on October 2, 2007.