Research Report

Preservation Prospect: The Holt House at the National Zoological Park, Washington, DC

by Virginia B. Price

The Holt House was built in the 1810s just outside the boundary lines of Washington, DC. It was constructed on a tract of land called Pretty Prospect, once owned by prominent Washingtonians: the Beall, Stoddert, and Mackall families.(1) Dr. Henry C. Holt acquired the house and just over 13 acres in 1844. He, in turn, sold it to make way for the National Zoological Park in 1890.

Within a generation, these basic historical facts were aggrandized. The construction date was pushed back in time to before 1805, effectively tying the house to the well-known Stodderts and Mackalls. Dr. Holt was conflated in the public imagination with someone else perceived as more prestigious: Joseph Holt, attorney general during James Buchanan's administration. Presidents Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren were said to have summered there.(2) Associations such as these lent an air of importance to the imposing, but deteriorating building. By the end of the 20th century, clarifying who actually was connected to the Holt House, as well as what it looked like originally, became paramount as calls for the building's preservation grew louder. Together with concerns about its run-down condition, questions about the little known, but still-impressive, suburban villa with a five-part Palladian plan resulted in a study by the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) in 2008-09.

Toward Preservation: Repair and Research, Assess and Record

Photographs reveal the dilapidated condition of the Holt House at the time of its acquisition by the zoo; the zoo then stabilized the building and renovated it.(Figure 1)(3) A hundred years later, the building was no longer in use by the zoo's administrative staff and it fell into similarly precarious shape. In 2001, however, its prospects brightened. At that time the zoo replaced the roof. The Kalorama Citizens Association rallied around the historic house and, in 2003, sponsored an assessment of the structure by a local firm, Quinn Evans Architects.(4)

|

Figure 1. Circa 1895 view looking to the Holt House. (Frances Benjamin Johnston Collection, Library of Congress.) |

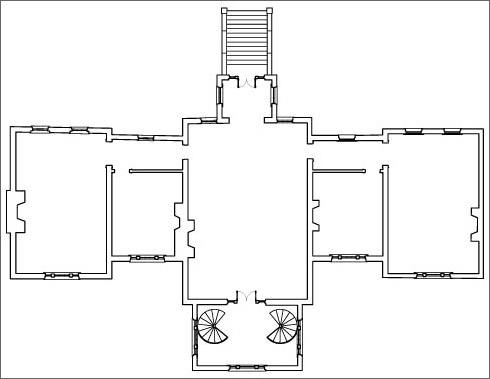

As a result of this collaboration between the zoo and the Kalorama Citizens Association, the prospect of preserving the Holt House gained traction. At the zoo's behest, HABS recorded the house with measured drawings.(Figure 2) The HABS drawings captured existing conditions, while the research and field documentation process highlighted areas for further investigation. The ongoing dialogue about how the building functioned is of particular importance to the Holt House. Many details are unknowable due to its condition and to the succession of alterations carried out by the Holt family and by the zoo. Asking questions of the building, of the documentary and material evidence, is essential if we are ever to discover its secrets.

Now mothballed as a safeguard against further deterioration, the Holt House awaits its future. The HABS project delineated its present form and outlined what is known of its past architectural configuration.(5) By distilling the building history of the Holt House and by working to piece together its evolution, the fieldwork behind the measured drawings represents an important step in the preservation process. Several of the resulting architectural queries are presented here.

From Present to Past: The Holt House before the Zoo

The building's Palladian-inspired plan is evident despite a cantilevered addition projecting off the main block.(Figure 3) It is likely that William R. Emerson, the zoo's architect in the 1890s, intended this feature to draw the Holt House into the zoo's picturesque landscape.(6) Emerson recommended dramatic changes to the building fabric, including excavating to create a full story on the ground floor. Other modifications obscured evidence of the house's pre-zoo appearance. For example, vertical, wood bars filled the ground-floor window openings by the time the zoo acquired it in 1890. It is unclear if sash was initially hung inside the bars, as seen in the basement windows of nearby (and near contemporary in building date) Arlington House. (Figure 4) Whether sash was hung in the window openings before the zoo's rehabilitation of the house is of interest because of implications for how the space was treated inside. Was it fitted out for social use by the Holts, or was it an unfinished cellar? In another example, the zoo's augmentation of the central room upstairs with a skylight, frieze, and ornamental moldings prompted a misinterpretation of that room as a ballroom.(7) The Colonial Revival-era embellishments erased clues to what was there before. What did the moldings and mantelpieces look like? Before the skylight, how was the space lit?

|

Figure 3. This perspective view of the Holt House, taken by John O. Brostrup for HABS in 1937, shows the cantilevered addition on the north elevation. This side of the house looked down into the Zoo grounds. (HABS DC-21-3, HABS/HAER/HALS Collection, Library of Congress.) |

|

Figure 4. The basement windows of Arlington House, with the bars and interior sash, are visible in this elevation drawing by Kathryn Faldwell, Jennifer Most, and Mark Schara of HABS in 2003. (HABS VA-443, HABS/HAER/HALS Collection, Library of Congress.) |

The exterior is less ambiguous. Even with Emerson's cantilevered addition and full ground floor, the Holt House is recognizable as a vernacular rendering of the five-part plan popularized by Andrea Palladio's treatise, the Quattro Libri dell'Architettura (Four Books of Architecture). At the Holt House, the hyphens are the same height as the wings, a proportional shift that disrupts the overall architectural rhythm (a-b-c-b-a) created by the five-part design. This divergence points to an otherwise unrecorded conversation between patron and builder. Was it intentional? Was it the result of building by pattern book, of inexperience or of improvisation?

Archival records hint at the restoration which Secretary of the Smithsonian Samuel P. Langley and Zoo Superintendent Frank Baker would have undertaken had funding permitted. They had architect Glenn Brown draw plans, for example, but these were not implemented.(8) For HABS this was important because Brown's drawings included an addition to the west. His scheme formalized the ad-hoc expansion of the west wing indicated on contemporary maps and, if erected, would present a more cohesive elevation than what Holt left behind. Today, the wall fabric yields little information about those (long ago removed) additions. Was, for instance, the space accessible from inside the house?

Sometime during the Holt family's occupancy use of space in the building shifted. Besides the additions to the west, they also changed the points of entry. Historic photographs show that the north vestibule was extended and exterior, wood steps were constructed leading up to it.(Figure 5) Verandahs were tacked onto the south elevation of both hyphens. HABS suggests that the south entrance pavilion was also an early addition.(9)

|

Figure 5. Schematic plan illustrating the late 19th-century plan of the house, with the north vestibule and exterior stair and the two spiral stairs inside the south entrance pavilion. The spiral stairs were also shown on Glenn Brown's drawing, and like the wood exterior stair to the north, were removed during the zoo's renovations. (Plan by Paul Davidson, HABS, 2009, for the author.) |

Moving past the zoo's and the Holt family's adaptations of the house to its original spatial configuration is a difficult, if not an impossible, quest. The earliest known reference dates to around 1840 when Amos Kendall rented the place. Kendall's daughters were married at the house and his entertaining solicited praise.(10) A guest mentioned "four rooms below," where there was dancing and card playing.(11) However, the location of those rooms in the building is uncertain. The ground floor had at least five rooms, and was not yet a full story. The advertisement posted upon Kendall's departure also paints a general picture, describing the house as having "...two wings and a centre building, rooms of every size, unique and beautiful in plan..."(12) Thus, the slips of documentary evidence prompt some familiar questions. How was the ground floor finished? Where were the original entrances and stairs, if the party took place "below"?

Conclusion

As a reminder of Federal-period Washington, the Holt House excites preservationists. Its form and spatial configuration intrigue architectural historians and warrant further study, studies that would build on what HABS was able to record. Questions, such as those posited above, linger unanswered. Although details about early 19th-century spatial arrangements may never be revealed, the Holt House remains an important piece of the landscape of the National Zoological Park.(13) The challenge for its advocates is to find an appropriate use for the house that respects its past as a suburban, Palladian-styled villa and ensures its future as part of the zoo's built environment. The Holt House is a preservation prospect indeed.

About the Author

Virginia Price is a historian in the HABS/HAER/HALS Division of Heritage Documentation Programs in the National Park Service. She may be contacted at gigi_price@nps.gov

Notes

1. For the chain of title, see the summary in HABS No. DC-21 that was drawn from the land records at the District of Columbia Recorder of Deeds.

2. Van Buren in fact leased Woodley, a historic house that is now part of the Maret School. See HABS No. DC-52.

3. Also see the photographs available online at the Library of Congress and Smithsonian Institution: http://memory.loc.gov and http://www.si.edu/ahhp/holthous/histfoto.htm.

4. Quinn Evans Architects, "The Preservation of the Holt House: Phase One," Report prepared for the Holt House Preservation Task Force of the Kalorama Citizens Association (2003).

5. This effort was informed by Gavin Farrell, "Smithsonian Institution National Zoological Park: A Historic Resource Analysis," Report for the Smithsonian Office of Architectural History and Historic Preservation (September 2004); Lara Pomernacki, "Holt House: Structural Alterations," Report for the Smithsonian Office of Architectural History and Historic Preservation (1997); and Denys Peter Myers, "Report on the Holt House: A Feasibility Study to Determine Restoration Goals," Report for the Smithsonian Institution (May 1977). It also benefited from conversations with Tina Roach, Quinn Evans Architects, 2009.

6. Regarding Emerson's intentions, Roger Reed to Virginia Price, 2009.

7. "Holt House ca. 1810" in Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Cortlandt Van Dyke Hubbard, Historic Houses of George-Town and Washington City (Richmond: Dietz Press, 1958).

8. American Institute of Architects Archives, RG 804, Series 5, Brown box 4, folder 29.

9. Site visit by author, April 2009. Most probably the bricks of the pavilion and the main body of the house are not interlocked. Presently, the south pavilion robs the main room of any exterior light save that from the 1890s skylight.

10. Daily National Intelligencer, November 21, 1839; Daily National Intelligencer, August 14, 1840. Amos Kendall was the postmaster general during Andrew Jackson's administration.

11. Letters January 3, 1838 and January 5, 1838, in The Letters of John Fairfield, ed. Arthur G. Staples (Lewiston, ME: Lewiston Journal Company, 1922), 185.

12. Daily National Intelligencer, June 30, 1841.

13. The significance of the Holt House property as a cultural landscape lies in its association with the mill once owned by John Quincy Adams and run, for a time, by a miller who worked for Thomas Jefferson at Shadwell; with Washington's earliest Quaker graveyard and later, on adjacent lots, with an African American cemetery; and with Rock Creek Park.