Interview

An Interview with Weiming Lu

by Antoinette J. Lee

|

Weiming Lu |

Weiming Lu is an internationally recognized urban planner and designer. He recently retired as president of Lowertown Redevelopment Corporation in St. Paul, Minnesota, which became a national model of successful central city revitalization through public-private partnerships. Lu received his Master's degree in Regional Planning in 1957 from the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. His career took him to planning positions in Minneapolis, Dallas, and St. Paul. Lu is known for his expertise in blending old and new design. He has served as a consultant and advisor on numerous public and private projects in the United States and abroad, including the reconstruction of South Central Los Angeles following the 1992 riots and the establishment of the Chattanooga Riverfront Corporation in Tennessee, the CentreVenture Development Corporation to revitalize downtown Winnipeg, Manitoba, and the United Nations Planning Team in Taiwan. Lu also served as member of the jury for the international design competition for the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games. Currently, Lu is a planning advisor to the Mayor of Beijing; a trustee of the Minneapolis Foundation; and a member of the Committee of 100, the organization of American citizens of Chinese descent; and as a panelist for the National Trust for Historic Preservation's Favrot Family grants.

Antoinette J. Lee (AJL), former CRM Journal editor, interviewed Lu on November 19, 2007.

AJL: Tell us about your childhood and early education. How did they influence your interest in architecture and planning?

WL: I grew up in an architect's family in China. My father was educated in China and France and was influenced by the Modernists. He translated Le Corbusier's book, Urbanisme, into Chinese. He also had a strong interest in classic Chinese literature and the revival of classic Chinese architecture. He followed the principles of Taoism, which emphasizes the harmonious relationship of man to nature and the universe. For this reason, he admired the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, who combined Western and Eastern aesthetics, as is seen most beautifully in Fallingwater. He taught me the importance of city design. It was not enough to design good buildings; architects should seek a proper relationship between buildings and their surroundings.

My father was a civil service high commissioner at the Examination Yuan under the Nationalist government. He practiced architecture and taught planning and architecture all his life. He enjoyed a close and warm relationship with his students beyond classes. When they visited our home, my mother often served food after their gatherings late at night. His teaching had a lasting influence on his students.

I was very impressed by his model of teaching and mentoring. When I had opportunities to lecture or to mentor students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Harvard University, Tsinghua University, Tokyo University, and the University of Minnesota, I tried to emulate his model.

AJL: Where did you study architecture and planning? Which professors were especially influential in your studies and steered you towards a career in planning and preservation?

WL: When I was growing up in Shanghai and Nanjing, I studied engineering in Jiao Tong University, which was the MIT of China. When the school closed in 1949 as fighting approached Shanghai, we moved to Taiwan, where I finished college. In 1953, I came to the United States to study engineering at the University of Minnesota. After I finished my degree in engineering a year later, I enrolled at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (UNC) in its graduate planning program. I received an assistantship to support my studies.

John A. Parker founded the Department of City and Regional Planning at UNC in 1946, which was one of the first planning programs in the U.S. based on broad interdisciplinary training rather than merely physical design. The faculty included Stuart Chapin, the model social science scholar and original author of the influential book, Urban Land Use Planning; Jim Webb, a skillful urban designer and practitioner, who contributed to the original plan for the Research Triangle Park; plus political scientists and legal experts.

At that time, the school was small—only about five students in each class. Not only did we receive a great deal of personal attention from leading figures in the planning field, we benefited from a broad planning education. I completed my course work in 1956 and received my M.R.P. degree in 1957.

Throughout my life, I benefited and learned from many other outstanding thinkers and academics. They included Kevin Lynch, who taught at MIT and wrote the influential books, The Image of the City [1960], What Time is This Place? [1972], and Managing the Sense of a Region [1972]. Lynch became a valued teacher and a good friend. I invited him to participate in planning projects later in my career. Other teachers and friends included Adlene Harrison, mayor pro-tem of Dallas, Texas; Bryghte Godbold, director, Goals for Dallas program; Phil Nason, a St. Paul banker; George Latimer, mayor of St. Paul; Norma Olson, a neighborhood leader; and Bishop David Preus of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America. I learned a great deal from all of these people, especially the art of rebuilding cities.

AJL: Where did you travel during this early period and what influence did these travels have on your outlook on planning?

WL: After working as a planner in Kansas City for two years, I saved enough money to go to Europe to look at planning and housing.

In England, I studied the work of the London County Council, the Greater London plan, and the new towns. On the Continent, I traveled to 10 different countries and studied the reconstruction that had taken place after the destruction of World War II as well as the many new towns being developed in Sweden and Denmark. Later, when invited to participate in a Polish and American preservation conference, I saw the reconstruction of Warsaw and the conservation of Krakow. They were especially inspiring and made a lasting impression on me. Serving as visiting professor at the Tokyo University gave me the opportunity to travel through different parts of Japan and experience both the intensity of urban life in a world metropolis and the tranquility of Zen gardens in Kyoto.

AJL: What was the status of planning in the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when you began your career as a planner?

WL: During the 1950s, the Federal Government was providing massive amounts of funding for urban renewal projects and interstate highway construction. These programs had a great impact on cities. Little attention was given to preserving the older fabric or to the significant displacement of the poorer residents. Political leaders were attracted to these federal programs and had a hard time resisting them. Many enlightened planners questioned the programs, as physical renewal did not bring social regeneration, but they could not stop them.

AJL: Tell us about your work in Minneapolis. What was happening in the city during this period and what did you do to establish historic preservation as part of city planning there?

WL: When I returned to the United States from Europe, I thought I might go to the West Coast for a job. Instead, while visiting Minneapolis, I was offered a job, where I worked for 12 years on a variety of planning efforts, including neighborhood conservation, downtown development, and the first metropolitan plan.

When I was in Minneapolis, I admired the elegant Richardsonian-inspired Metropolitan Building, which had a beautiful atrium. Unfortunately, it was demolished in 1961 as part of a major urban renewal effort that saw about 60 acres of the downtown area razed and replaced. Seeing the destruction of the Metropolitan Building, I was saddened and determined to do something about it.

As I was working on the downtown plan and the citywide urban design study, I soon initiated and engaged architectural historian Donald Tolbert of the University of Minnesota to do a historical survey, and I retained noted legal expert Richard Babcock of Chicago to recommend critical provisions for state historic preservation legislation. Working with the Minneapolis Committee on Urban Environment, I was able to get the Minnesota state legislature's attention, and a bill based upon our recommendations was introduced in 1971. I testified at the capitol and recommended two additional provisions. One was for parking variances for historic rehabilitation, and the second was a stay of demolition. Both provisions passed with the Minnesota Historic District Act that year. The renovation of Butler Square occurred soon afterwards. That was the beginning of preservation in Minnesota cities and the rest is history. Many recognize that this act, plus the Tax Increment Financing Act, were introduced in Minneapolis but actually benefited the whole state. Our downtown plan also brought about Nicollet Mall, the skyways, the fringe parking system, and the recovery of downtown. Our work around the University the Minnesota also brought collaboration between town and gown and the conservation of neighborhoods close to the university.

AJL: Tell about your subsequent work in Dallas, Texas. What was the status of historic preservation in that city and what did you accomplish there?

WL: I joined the Dallas Planning Department as its deputy planning director for urban design in July 1971. The city asked me to head an active urban design program as an expansion of the planning department. I initiated a broad range of activities, from historic preservation to downtown development, from arts district to escarpment protection. I recruited a number of talented staff members from different parts of the country.

Soon after I joined the city government, I was invited by former mayor Wallace Savage to help save the Swiss Avenue area from deterioration and destruction. After study, I recommended a historic district designation as a way to save the neighborhood. The result was the Swiss Avenue Historic District, the beginning of the Dallas preservation movement. Later, preservation spread to other sections of the city.

The Texas School Book Depository that played such a key role in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 was about to be converted to a commercial museum. We first went to the State Historic Commission to seek state historical designation, but were stalled by residents who wanted to have the building torn down altogether to erase that awful memory. Of course, we could not just stop there. After several years of work and hundreds of meetings, we succeeded under home rule to bring about local designation for 55 acres, including the Book Depository, and substantial down zoning of the area.

Later, we persuaded Dallas County to acquire the building for its administrative offices, and saved the sixth floor for a historical museum. These successes grew out of our sense of historic responsibility, sensitive preservation guidelines, and realistic economic studies to prove that the area could be viable and provide developers and property owners with a reasonable return. And above all, our success in gathering political support helped us prevent demolition and achieve that important preservation mission. Many believe that the explosive development in the 1970s and 1980s would have otherwise wiped out the downtown district, including the Book Depository.

Among our other initiatives was the protection of the sensitive escarpment, which was a bluff along the southwest side of Dallas. Without protection, the bluff could have become severely eroded. We limited the intrusion of roadways, developed a number of ecological guidelines for development, and had the city acquire 300 acres of the sensitive zone as open space.

This was a critical period in the development of Dallas. I was also lucky to work with a number of wonderful leaders to envision an arts district. Many enlightened people from the city government and the private sector committed themselves to the arts district, which brought together the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, the symphony, ballet, opera, and theater. However, this period did not last and the working environment changed drastically when a developer was elected as mayor. Support for urban design and preservation soon disappeared, and I regrettably believed it was time for me to move on.

AJL: Much of your career was focused on the Lowertown area of St. Paul. Would you tell us what Lowertown was like in the late 1970s? What was the plan for the area?

WL: In 1979, I began work with the Lowertown Redevelopment Corporation as director of design and became the organization's president in 1981. This opportunity allowed me to be my own boss and to exert my own skills on the area. I remained there 26 years. Seeing that our mission had essentially been accomplished, I decided to step down in 2006. The corporation decided to shut down after a strategic review. I am pleased that we have set up a Lowertown Future Fund with the remaining resources to support the community we have built.

One must understand how Lowertown developed historically. The area grew up during the steamboat days along the Lower Levee and then further expanded during the railroad era. Between 1880 and 1920, the area filled in with monuments to the early transportation era. As the transportation systems changed to highways and automobiles, the area fell into disuse. In the late 1970s, Lowertown was a deteriorated warehouse district.(Figure 1)

|

Figure 1. This photograph shows the Lowertown area of St. Paul, MN, before revitalization. The area was characterized by empty lots and underutilized older buildings. (Courtesy of Weiming Lu.) |

From the beginning, we hoped to transform the place so that people would come back to the city. Even with abandonment and deterioration, the area had a number of strong assets, including its downtown location, its Mississippi riverfront, and many fine historic buildings, and we believed we needed to create a new vision to rejuvenate the area.

Former St. Paul mayor George Latimer laid the foundation for the Lowertown Redevelopment Corporation, a private organization with a public purpose. An enlightened and dedicated eight-member board of directors was made up of business leaders, pastors, and others who represented a good cross section of the community. The corporation undertook the daunting challenge of renovating the Lowertown district, which covers 12 blocks of historic buildings, abandoned rail yards, and riverfront, making up one-third of downtown St. Paul.

To accomplish our mission, the corporation focused on three types of activities: first as a design center to create a new vision for the area; second as a marketing office to make people believe in our vision and the market potential for the area and willing to invest; and, third, as a development bank to fill the gap in financing.

At the beginning, our former mayor promised to our funder, the McKnight Foundation, that $10 million would result in $100 million in investment. For an area that suffered from decades of disinvestment, that was quite an ambitious goal. Between 1969 and 1978, there was $22 million in investment in this 180-acre area, of which $16 million was for an industrial plant and only $6 million for the rest of the area. Nevertheless, the foundation shared our broad social objectives in renewing the historic district, building affordable housing, and adding jobs, and thus boldly set aside funds and supported our mission.

Through persistent efforts and many successes and failures, our corporation actually generated $750 million in investment, or seven-and-a-half times the original goal. Through discipline and successful negotiations, the corporation attracted $5 to $35 dollars in public and private money for every dollar it invested in a project. The tax base increased six-fold from $850,000 in 1979 to $5 million in 2005. The project resulted in 2,600 housing units and added and retained 12,000 jobs. The leveraging or multiplying effect was incredible. The social goals achieved were most satisfying.

With the concentration of old warehouses and factories, we saw the potential for fostering a sense of place. We believed that new development should harmonize with the existing fabric of the community. The corporation's unique partnership with the City of St. Paul and the private sector resulted in a successful development strategy for the district.

The goal of Lowertown was to "create an environment where creativity is cherished and entrepreneurship is supported; where one can fill the needs for community and provide an outlet for a civic spirit." From the beginning, we aimed to build a community, rather than just do projects, and promoted a vision for a new urban village. This vision called for a place with thriving businesses and plentiful jobs.

Throughout the process, we provided housing for people of all ages and economic backgrounds. We were committed to avoiding displacement. Each project was different with different types of housing, different financing, and different project sponsors, particularly nonprofit groups. We also worked with Section 8 projects and senior citizen housing. We retained and expanded the single room occupancy facilities. We used city financing and foundation grants to subsidize some of the projects. Sweat equity was an important part of the artist housing project. Today, 25 percent of Lowertown's housing is dedicated to people with low and moderate incomes. It also boasts one of the highest concentrations of working artists in cities across the nation—500 and growing at last count. Of course, the area also includes both rehabilitated and new housing for a range of income groups, including some expensive housing as well.

AJL: Please summarize the evolution of Lowertown over the next two to three decades. What tools were available for the revitalization of the area? How did you proceed? What did you expect would happen? Did the redevelopment of the area turn out as you envisioned it would?

WL: The Lowertown Development Corporation played a number of important roles. Sometimes, we sought the support of our political leaders in the design and development process. Other times, they asked for our advice on specific projects. Sometimes, the corporation mediated disputes between developers and city agencies. When a suitable compromise was unattainable with developers, the corporation took its case to public forums. We also cultivated media coverage to influence public opinion and rally public support. We worked closely with neighborhoods and established trust and credibility with them.

We implemented design guidelines for new and rehabilitated projects. We preferred to rely on creative dialogue rather than regulatory power in our design process. We strove to preserve the historic context through a few selective guidelines, while giving architects maximum room for creativity.

One of the first steps we took was the survey of historic properties in the area and the nomination of a 12-block area of Lowertown to the National Register of Historic Places. With the listing in place in 1983, we marketed the area's potential for generating millions of dollars in historic rehabilitation tax credits. We attracted investors from near and far, including developers from Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, and Montreal, as well as the Twin Cities. In the end, all but 4 of the area's 46 buildings were successfully rehabilitated. One was lost to fire, another to demolition after failure to persuade the owner to rehabilitate, and the other two are to be rehabilitated in the future.

We also used funding from a number of public and other sources, including Urban Development Action Grants (UDAG) from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, tax-exempt financing, and loans and loan guarantees from the Lowertown Redevelopment Corporation. Our financing also included foundation grants, developers' equity, and tapping the fundraising capacity of nonprofit organizations. For example, the $20 million public television station was built debt free. Minnesota is a generous community.

Today, Lowertown features apartments, condominiums, townhomes, a YMCA facility, retail space, restaurants, galleries, office space, and underground parking. The area also has multiple high speed Internet networks and satellite uplinks, enabling us to create a cyber village for the creative community.(Figure 2)

|

Figure 2. Today, the Lowertown area of St. Paul boasts many historic buildings that have been rehabilitated and used for commercial and residential functions. (Courtesy of Weiming Lu.) |

Reflecting on the past, I am pleased we have saved many fine buildings, built a diverse neighborhood and a creative community, and established many amenities in the district and on the river bend. We have overcome significant obstacles and set the stage for riverfront development. However, some of the projects were much larger than we would have liked. Some of the projects could have been better designed, if there had been opportunity for creative dialogue.

AJL: How did the Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary emerge as a key factor in the revitalization of the area?

WL: Experience tells us that urban development is most successful when there are natural areas nearby, where people can escape the city for a quiet walk or a moment of reflection. The Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary serves as this green amenity for the Lowertown and adjacent East Side neighborhoods of the city.

The land that became the sanctuary was taken over by rail operations, including maintenance facilities, by the early 20th century. In the 1970s, the area was largely abandoned and contaminated. Community leaders hoped that the land could be reclaimed and restored to a natural area and form a connection between the Mississippi River and the Lowertown area.

This dream became reinvigorated in the 1990s. At the invitation of the McKnight Foundation and the East Side neighborhood, the Lowertown Redevelopment Corporation joined in the effort to transform this floodplain. Our consultants showed us a way to capture water from the natural springs in the area that lay just below the surface of the land. We also developed a plan to create a trail hub in the area that would allow people to walk or bicycle between the East Side, Lowertown, and the Mississippi River.(Figure 3)

The late Congressman Bruce Vento was an early supporter of the project, and his death in 2000 inspired others to secure Federal Government funding to purchase the land. This was accomplished in 2002. Over the succeeding years, we sponsored cleanup events to remove tons of debris. The Environmental Protection Agency's Brownfields Cleanup Grant Program and other sources provided funds to remove the contamination and cover the area with four feet of clean soil.

The sanctuary was opened to the public in May 2005 and has attracted many residents, artists, and visitors. It is a beautiful park that offers a true natural experience in the heart of St. Paul. Not only does it offer a beautiful creek, wetlands, and views of the downtown skyline, it also provides glimpses of bald eagles, hawks, songbirds, and other wildlife.

AJL: Now that the redevelopment of Lowertown is basically complete, what lessons did you learn from the efforts that are applicable to other revitalization projects in the United States?

WL: No urban rejuvenation is ever totally complete. As one phase is complete, another phase will begin. I am pleased that the foundation we established for Lowertown will carry the development to the rest of the area and the Mississippi riverfront. Congress has provided $50 million for the restoration of the Union Depot and Ramsey County has spent another $50 million for the acquisition of the Depot Concourse and the riverfront land. The State of Minnesota has appropriated $70 million as match for federal support of a light rail system. The depot restoration will be completed by 2012, and the light rail will connect the area to downtown Minneapolis two years after that. New housing, an arts center, and marina and park on the riverfront will help us build the River Garden as we have envisioned, thus doubling or even tripling the investments in Lowertown. They will help us build the next urban village in Lowertown.

From my experience working in three American cities—Minneapolis, Dallas, and St. Paul—and from my work as an advisor on dozens of other cities, I have learned the following lessons:

First, successful city design must begin with strategic vision and incremental action. Strategic vision helps us set general direction and builds public support for a project. This vision must be carried out incrementally and patiently with concrete steps.

Second, successful city design is an institutionalized process. Planners must develop expertise in the full range of city design activities, including urban form and image, behavioral science, market research, legal instruments, administrative processes, and financing. Only then can planners help political leaders carry out plans and programs.

Third, successful city design requires specific guidelines and creative alternatives. The preparation of design guidelines requires design sensitivity, understanding of economic reality, and familiarity with the legal framework for design. Alternative designs may be used to stimulate dialogue and encourage better solutions.

Fourth, successful city design must respond to the market. Market forces should never dictate decisions affecting city design, but planners need to understand the market and meet its demands.

Fifth, successful city design must respond to people's needs. By engaging people in the design of the public realm and private spaces, we increase the chances of success.

Sixth, successful city design depends on creative talent. Once designers are engaged, they need to be put in a creative environment where they can do their best work.

Last, successful city design requires effective communication and political savvy. It is people, not bricks and mortar, that have the most influence on city design. People are my best teachers. Learning from them is a lifelong privilege. Marshalling needed political support for selected designs requires political savvy and a network of partners in the public and private sectors.

AJL: Tell us about your work in other cities in the United States, in China, and in other countries abroad. What are the universal approaches to revitalization? What approaches are unique to their countries?

WL: Each country has its own culture, so there is no universal approach. However, every country could learn from the others. When I travel to China, I am reminded of China's long history, which had the tradition of relying on the rule of men rather than the rule of law. While there I try to share with their planners how to construct effective legal instruments, how to make their decision process more transparent, and how to work in a market economy. However, to be effective, I also must find ways to influence the top leadership.

As China is going through such rapid development, equivalent to going through industrial and information revolutions simultaneously, Chinese leaders and planners have tremendous opportunities and challenges to preserve and develop their cities. Besides serving as advisor to Beijing, Taipei, and Singapore, I have helped sponsor Chinese mayors and planners to visit the Twin Cities and the United States. I hope these exchanges will help them find useful solutions to their many challenges.

While China is suffering from unsustainable development, other countries, too, have had their own experiences and learned from them. For examples, the Yokohama MM21 project in Japan suffered from overbuilding and the London Dockyards in the U.K. was troubled from the outset from an inadequate infrastructure. The important thing is that all cultures learn from themselves and others, make proper adjustments, and find recovery.

AJL: Looking back on your career, what were the most important observations that you would like to pass on to the next generation of preservation planners?

WL: The importance of historic preservation is that it will help preserve each country's unique culture and history. Today, there are so many mega projects around the world that look alike, regardless of the country. Each country and each city has its own character that should be valued and preserved. Because globalization is making cities look more alike, I believe we must face this challenge and reverse this trend. Thus, whenever I am in China, I give lectures on the Shan Shui city concept, tracing the mountain and water spirit, which for centuries formed an important foundation for Chinese landscape design and city planning. I hope the Chinese will rediscover their glorious heritage.

In order to achieve the preservation of cultural heritage, we need the interdisciplinary skills of planning and preservation so that we can make promises and deliver on them. We must be open to new ideas where visioning and re-envisioning are continual processes. Nothing significant can be done overnight; it requires vision and persistence. The authentic city must be built on real architectural heritage rather than on a set formula and current fashion. Some of the best ideas come from the people and their aspirations and voices. Working from the bottom up and empowering people always are most meaningful and rewarding to me.

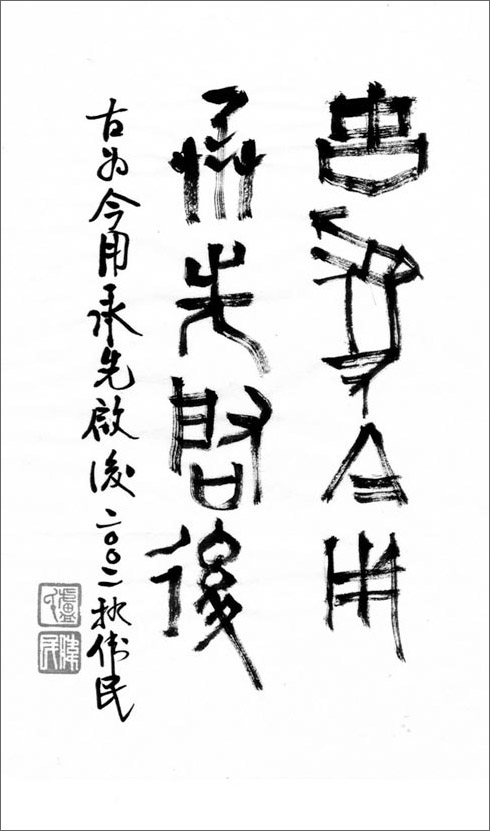

As a person who has spent nearly one third of my life in China and two thirds in the United States, I am a product of two cultures that do not always dwell together harmoniously. Generally speaking, Chinese culture stresses continuity, while American culture values change. As one who has had to straddle both cultures, I often struggle with these competing ideals.(Figure 4)

|

Figure 4. This calligraphy work by Weiming Lu says, "Let the past serve the present, learning from the preceding generations and inspiring the future ones." (Courtesy of Weiming Lu.) |

Over the years, I have come to the conclusion that continuity without change brings stagnation and deterioration, and change without continuity brings instability and uncertainty. The challenge for me is to strike a sensitive balance between the two in my work and my life.