Article

Women's Contributions to the Historic American Buildings Survey, 1933-1941

by Amy Gilley

A New Deal era program, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) was a curious marriage of the American historic preservation movement originated in large part by women and the "gentleman's profession" of architecture. Whereas one helped raise public awareness of the nation's architectural heritage, the other adhered to traditional gender roles in the architectural and landscape architecture professions. In its early years—1933-1941—HABS thus presented a unique opportunity for women to step into the public realm both informally and professionally as cultural stewards, specifically as historians and architects.

The role of cultural historian and steward as exemplified by preservation groups like the Mount Vernon Ladies Association was in alignment with traditional roles for women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; the woman architect faced greater challenges, starting with access to education.(1) Both groups, however, faced the similar challenge of being taken seriously as professionals in these male-dominated fields. Many of the women who served as architectural historians or who provided critical information to the HABS architectural survey team have been unrecognized in the official reports and history. Likewise, the correspondence and other records generated by the survey between 1933 and 1941 confirm that the employment practices of this federal project, a work relief project for out-of-work professional architects and photographers, mirrored the experiences of working women within the architectural profession in the early 20th century.(2)

For a woman, establishing oneself in the male-dominated field of architecture required tremendous initiative.(3) The HABS supervisors were men; the majority of the draftsmen were men, as were the historians; and yet, women's participation in these projects contributed to their success.

Most women employed by HABS during the survey's initial run worked as stenographers or secretaries. The records from this period suggest that women delineators were likely to be hired if the male architect in charge of the HABS district office had a connection (usually through teaching) with a school that trained women in architecture or landscape architecture. Women holding the title of HABS historian were equally rare. Many secretaries unofficially took on that role without the benefit of the increase in pay. The criteria used to appoint the district officer for each survey office all but assured that women would not be assigned that leadership role.(4) However, the records show that a number of women had, in fact, assumed this level of authority, albeit unofficially, in district offices across the country.

HABS also benefited tremendously from a vast social network of influential women who voluntarily supplied contact information, historical data, architectural drawings, and old photographs of historic buildings and sites. These women volunteers, many of them "imbued with the cult of domesticity, which appointed them guardians of society's culture and morals," took their cultural stewardship responsibilities very seriously and actively supported the survey in their communities.(5) The architect John P. O'Neill, head of the national HABS office in Washington, DC, said of the Daughters of the American Revolution, a national patriotic women's organization for descendants of people who helped bring about American independence, that it was "one of the most active organizations in calling attention to the need for marking historic sites and monuments or for actually providing funds for the work."(6) He advised Northeastern Pennsylvania HABS district officer Thomas H. Atherton that "you would do well to contact your local D.A.R. [sic] chapter, at least as a first step in working out your plans for Wyoming Battlefield," an American Revolutionary War site in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. The Daughters of the American Revolution organization was among a number of women-led historical organizations upon which HABS depended for leads and other information on suitable candidates for documentation.

Women's Work

Although the work relief projects established under the New Deal beginning in 1933 varied in focus, their purpose was the same: to relieve unemployment. These early programs generally involved construction jobs for men, offering few, if any, opportunities for women. When the Works Progress Administration was established in May 1935, it included a single division for women and white-collar professionals.(7) Due to the pressure to employ people quickly, women were also restricted to certain types of jobs: "work already generally accepted as women's work: sewing, housework, and care for the sick and young."(8)(Figure 1)

Although Ellen Sullivan Woodward, the first director of women's and professional projects at the WPA, believed that it was her division's responsibility "to see that employable women on relief rolls who are eligible for work receive equal consideration with men in this program,"(9) the WPA's employment quotas as well as general cultural biases(10) limited women's participation. Until the 1940s, WPA policies restricted the number of women participants to a maximum of one sixth of all WPA enrollees. Even though the numbers of unemployed women on relief equaled that of men, the WPA steered professional opportunities first to "heads of household," who were typically men. "As a general rule, a woman with an employable husband is not eligible for referral, as her husband is the logical head of the family," regardless of her qualifications.(11)

The WPA rules made little sense to professional women who were definitely in need of work, but were made invisible by the stroke of a bureaucrat's pen in Washington, DC. Phyllis Hamblur of Seattle, Washington, spoke for many struggling professional women when she wrote to Harry Hopkins, the federal relief administrator in charge of the WPA, about her predicament. "I am a graduate librarian," she said, "and in the past four years [roughly 1931 to 1935] the only work I have been able to find is that which I have done under the government's supervision [prior to the WPA], so you see the 'white collar woman' has had no easier time than the manual laborer to find work."(12)

A preliminary review of HABS administrative records from the WPA phase of the survey has shown that HABS did not veer from this average. Women comprised less than one quarter of the staff and were employed in the lower paying positions of clerk, clerk typist, and senior clerk.(Figure 2) Occasionally, a woman was placed within the professional category as a historian but rarely as a draftsman.(13) Some offices had no women on staff at all. One of the main reasons for the disparity may have had to do with the general attitude that "the work of H.A.B.S. [sic] requires extensive architectural training and experience, combined with technical drafting ability above the average," which few women—and, for that matter, few unemployed men—actually had unless they had trained or worked previously in a drafting room of an architectural office.(14)

The Delineator

The role of paid women HABS employees reflect the limited opportunities for women professionals, particularly in architecture, during the 1930s, as well as their persistent attempts to break through these professional barriers. As a federal project designed to employ out-of-work professionals, HABS offered architects a chance to survey existing structures, demonstrating their knowledge of historical construction. This opportunity was an exciting one for women who had been hindered by a belief that women were incapable of such work. Henry Frost, the founder of the Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture pointed out that—

design, while still of importance, is more dependent upon those who excel in construction, in writing of specifications, in the ability to estimate costs and returns and other practical matters…there seemed to be a consensus of opinion that they [women] were not as able to do work in engineering and construction as men.(15) |

Historian Dorothy May Anderson has noted that, prior to the 1920s, people objected to women in architectural and other professional offices on the grounds that "women in a drafting room with men would disrupt the office morale" and that "women could not be used as superintendents on a job and could not run various necessary errands connected with construction."(16) Women also had a difficult time acquiring educational training.(17) Few architectural or design programs admitted women, and social and familial pressures discouraged them from entering degree programs and professions long dominated by men. Anderson recounts that Martha Brown Brookes Hutchenson's family told her that "she would be socially ostracized and dishonor her family if she persisted in entering M.I.T. to study landscape architecture."(18) Anderson summarized this cultural mindset succinctly—

The average girl, however serious she was in her work…regarded it as more or less a temporary vocation which would cease with marriage. She accepted an entirely realistic attitude that since she was training in preparation for a probably limited period of professional activity, she need not go as far in her training as her brothers. Primarily, she [wanted to learn] in the quickest possible time how to design and construct, and above all how to draft.(19) |

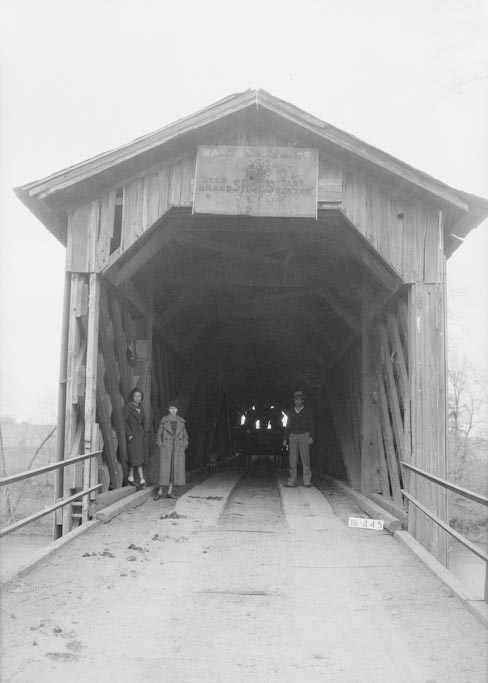

As a mirror of the larger professional world, only when women had access to drafting classes and influential and sympathetic male professors, did they appear on the HABS work roles. In only a handful of states—Alabama, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Oregon—are women listed as delineators on any measured drawings. With the exception of New Jersey, the district offices in those states had ties with schools that trained women. The Alabama district office, under the leadership of architect E. Walter Burkhardt, a professor at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University), had the largest number of women delineators because the design program at that school admitted women.(Figure 3) The Historic American Landscape and Garden Project (HALGP), a subgroup within the HABS district office in Massachusetts, consisted mostly of women, many of them former or current students at the Lowthorpe School of Landscape Architecture, Gardening, and Horticulture for Women. This school, in particular, was a leader in providing an avenue for women seriously interested in careers in landscape architecture.

Located in Groton, Massachusetts, the Lowthorpe School opened in 1901 following the elimination of the landscape architecture department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).(20) The first school of its kind for women, Lowthorpe offered practical training in the gardening arts. R. Newton Mayall provided the critical link between HABS and the Lowthorpe School, working simultaneously as HABS project supervisor and instructor at the school until dismissed from the survey in 1937 for unknown reasons. While with HABS, he had recruited at least one of his Lowthorpe students, Margaret Webster, a 1931 graduate, as a landscape architect. The large number of delineators and project managers on his teams suggests in part that he viewed the survey as an exceptional educational and employment opportunity for his students.(21)

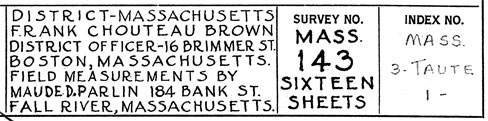

Overall, women delineators employed by HABS accomplished the same amounts and types of work as their male counterparts. Maude D. Parlin, a delineator in the Massachusetts district office, noted that she not only checked the measurements at the Rueben Fish house (later delineated by Carmen di Stefano) and measured the Nathan Dean House, but also researched Assonet, spending a total of 22 hours working Monday through Thursday, and she multiplied her hours by 90 cents for a total wage of $19.80.(Figure 4) She added that "100 miles a week for travel for research and for measuring is a fair average."(22) Her experiences matched those recorded by the male delineators. This work was unusual for a woman and contradicted the prior claims that women architects were unable to do the physical work involved in architectural construction.

Three other women involved in the Massachusetts survey—Webster, Louise Rowell, and Rylla B. Saunier—documented more than 30 gardens as part of HALGP. A study of the drawing sheets from these projects suggests that Webster, Rowell, and their supervisor, Mayall, took turns as field worker, delineator, and project manager, shifting their roles depending on their workloads, expertise, and the requirements of a project.(23) Most HABS project teams operated in this fashion, which suggests that in those rare cases where women worked on field and drawing teams, they performed at levels comparable to the best trained male delineators then employed by HABS.

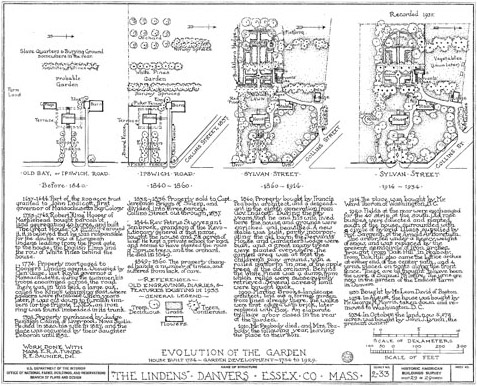

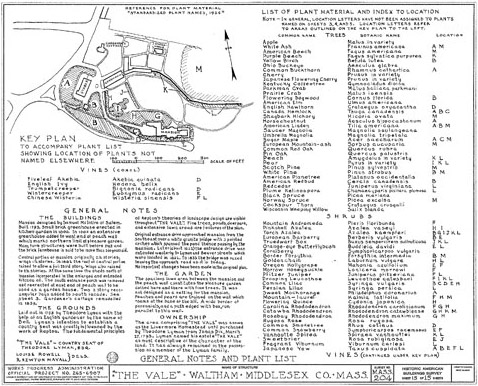

Saunier first worked with Mayall in 1935 on the measurements for the Lindens, one of the early projects of HALGP.(24) On that project, she helped with field measurements and drew the final sheet showing the evolution of the site over time, including the changes in street names and planting designs.(25)(Figure 5) Webster drew architectural details of the Squire William Sever House but focused primarily on the planting design for that site.(26) She also worked with Mayall on detailed plant lists and grading plan drawings for the Vale.(Figure 6)

|

Figure 5. Rylla B. Saunier helped with field measurements and drew the final sheet showing the evolution of the landscape of the Lindens in Danvers, Massachusetts, over time, including the changes in street names and planting designs. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

|

Figure 6. Louise Rowell co-produced this detailed planting list for the Vale in Waltham, Massachusetts. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

Rowell appears to have been the team's architectural expert, completing the majority of the fence details and other garden structures for HALGP. She was also proficient in planting design and historical research. Rowell and Webster worked together on several projects, both checking measurements and producing drawings. Their proficiencies at drafting details were, to an extent, a reflection of the training women received at Lowthorpe and other schools, where knowledge of architectural details and landscape construction was an important part of the curriculum.

For all their extraordinary work on the HALGP, the women nevertheless remained invisible to many within the HABS bureaucracy. Their names were not the first to come to mind for promotion from within the ranks. When Mayall was dismissed from the project in 1937, Frank Chouteau Brown, the northeast regional officer for HABS, recounted to Washington that "When they asked me, first, to get some one to head up the work, and 'take his place' over night; I laughed at them; as there is no one else about here who knows anything about Garden historic research."(27) In separate correspondence, Brown elaborated that "several people on the (HALGP) project are not specially trained to be conversant with the material;" yet, he promised to "see that such simple things as gates, fences, and garden houses are correctly measured and presented." Although the details are a mystery, Webster was given the title of landscape architect shortly after Mayall's departure.

This experience is not unlike that of many women in landscape architecture. Many women architects found success through a marriage to an architect, for "marrying an architect increased the likelihood of having a husband who understood and had sympathy for one's work. Marriage to an architect also solved the need of finding a job, working part-time, and coordinating vacations, work schedules, and care of children."(28) Architecture remained a dominantly male profession, with a few women such as Frost's partner Eleanor Raymond, breaking the barriers.

The Secretary

A secretary in the Albany, New York, district office of the Survey, Helena Mayer's experience was probably more typical of a female HABS employee than that of the delineators Webster, Saunier, or Rowell. Mayer's name first appears in the historical record in a September 1936 letter to Brown from Albany district officer Andrew L. Delehanty, in which Delehanty informs Brown that "Miss Mayer will be able to take you to the offices in Schenectady, Troy, and Amsterdam if there is time. She is a very competent driver and has a splendid knowledge of the work."(29) Delehanty frequently commented favorably on Mayer's knowledge and abilities in his letters, and the record of their correspondence reveals the extent to which the Albany office relied on her to keep the office going.

On at least one occasion, Delehanty hinted at his frustration with the rigid hierarchy of the federal system that prevented him from giving more administrative responsibilities to Mayer, who in addition to general secretarial work prepared HABS historical reports and other documentation.(30) He complained to Brown that—

I have been greatly hampered in my fieldwork by spending a week at a time chasing a payroll from one department to another. I have a most competent secretary who could do this for me but they will not honor her presence in most of the departments because she is not authorized to do it and is not the 'Head' of the department.(31) |

Proof of Mayer's central role in the Albany office survives, not in the form of documented salary increases or letters of promotion or commendation, but in Delehanty's request on Mayer's behalf for an exemption from the WPA rules pertaining to the employment of non-relief workers of which she was one—

The fourth non-relief case is my Secretary and is one of the four who simply cannot be replaced. She handled this work two years ago for Mr. Norman Sturgis, is thoroughly acquainted with all sides of architectural work, understands all the routine of the WPA and because of her knowledge, intelligence, and capacity for work, I am relieved of all office routine and can devote my entire time to the field and offices in my district. If I were forced to drop her the project might just as well close in the Albany office…Miss Mayer is able to assist in the checking of the drawings, and understands just how to provide the men with the proper materials required by them.(32) |

Brown echoed Delehanty's sentiments a year later: "Miss Mayer is perfectly capable of running the routine of the office and WPA contracts for the whole state, if necessary or desirable… ."(33)

Brown later wrote that "Miss Mayer would make a very good 'coordinator,' as she had a certain amount of experience… ."(34) In another letter, he recognized Mayer's administrative ability as critical for maintaining the Albany office: "Mr. Delehanty is particularly muddle-headed in regard to procedure—but this matter, Miss Mayer got to understand quite well and he was content to leave it within her hands; so between them, a fairly effective progress seemed to be possible."(35)

Unofficially, Mayer was Delehanty's equal in the operation of the Albany office. She communicated directly with the central HABS office in Washington, DC, requesting help with the reinstatement of the survey at Albany in 1937, for instance, and people relied on her for information on projects and personnel. She knew the desperate personal financial circumstances of many on the Albany staff. "Many of them [the unemployed]," she wrote, "are from Ludlum Steel Company and I understand there are some good draftsmen amongst them."(36) Her boss also trusted her to make decisions. She told Washington that "Mr. Delehanty thinks you better write to me in care of Dr. Adams, for quick action at this time as he is out with some of the men in the field…calls me each night on his return to the city."(37)

Mayer, it seems, was also an astute reader of bureaucratic politics and understood when to contact Washington indirectly and when to follow protocol. For example, when conflict arose in 1938 between the New York State Museum—the state sponsor of the survey after June 1937—and the HABS central office over the direction of the survey and ownership of the drawings, she unofficially disseminated information: "I am not writing this to Mr. O'Neill as of course I have no right to pass this information on officially, but I am sending it to you along with a carbon copy and if you feel it advisable you can pass it on to Mr. O'Neill."(38) Brown, in turn, forwarded the information to O'Neill in Washington. "I do not understand the entire details of this as I only got occasional letters from Miss Mayer and Mr. Delehanty during that time," he wrote, "but I am sure Miss Mayer would be glad to give us the facts which might help you in making your decision."(39)

Like many women in the WPA, Mayer faced an uphill battle to remain on the HABS payroll after the WPA program ended in the summer of 1937. "I know that Mr. Delehanty has written to you that I was dismissed from the project because I am single and orphan, having no dependents," she wrote O'Neill in 1938, "but then we have to live too you know….I am over the 30 mark in age and it is impossible to get work."(40) Correspondence between her and Brown from April 1938 indicates that she was working on a voluntary basis to complete projects.(41)

According to Brown, Mayer was still involved in the survey as of January 1941, although working through Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. "The last word I had from Miss Mayer," he noted, "she seemed to be very much worried because she said the [New York State] Museum was lining up and adding to their report of work accomplished, all the material left over from the HABS."(42)

The Historian

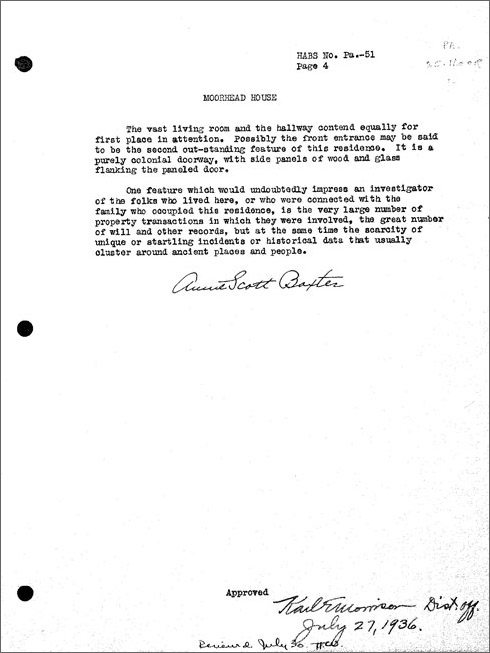

Women brought on as HABS historians generally enjoyed greater independence and, at times, more respect than their secretarial counterparts, but they nevertheless had to work within a male-dominated environment that put gender ahead of professional qualifications, experience, and other considerations. Annie Scott Baxter, a historian in the Northwestern (Erie) Pennsylvania district office—an office plagued by poor management—wrote candidly about the managerial style of her supervisors, William Mann and Karl Morrison, and the dim prospects for her re-employment in the Erie office once the WPA funding for HABS had dried up in the summer of 1937—

I am still on "relief" and there seems to be no prospect of getting any work so long as Bill Mann and Carl [sic] Morrison control the situation up here…the same drinking, loafing and other conditions still flourish... Just today I learned from an ex-actor (and a mighty poor one at that) that he is on the job at the Custom House and Library. He has only been a resident of this city for two years, is single, and yet a position is handed to him, while I have been (personally) in the past thirty or more years a tax-paying citizen, a resident of this city for sixty-five years; I am a recognized genealogist and research historian, have been a teacher, business executive, etc etc on newspapers as "free lance" and as advertising manager. Have a knowledge of art, architecture (four years in H.S.) about two years study under MaCrum and all the W.P.A. can assign me is "sewing"….(43) |

While employed as a historian in the Erie office, Baxter completed more than 30 historical reports on buildings spread over several counties, and she produced a lengthy outline history of the development of the architecture of the region that highlighted its Greek revival architectural heritage.(Figure 7) She also took evening classes in architectural drafting and blue print reading "to gain more knowledge than I had," she wrote, "so as to reconcile whatever deficiency might develop in the work."(44)

|

Figure 7. Historian Annie Scott Baxter produced several historical reports for the HABS district office in Erie, Pennsylvania, including this one for the Moorehead House in Erie County. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

For all her accomplishments in the Erie office, her experience there was bittersweet, and correspondence from the period of her employment suggest that matters of a personal nature might have played a role in her dismissal. Erie district officer Howard Hicks told Washington that Baxter had "a very disagreeable disposition and if she does not have her own way, she is ready to fight. She is very quarrelsome and does not seem to be able to get along with anyone in the office nor with whom she comes in contact throughout the WPA organization."(45) Baxter, however, saw things differently—

Since Mr. Hicks came to work, I have tried by every effort to give him assistance in every part of the work I am familiar with. I found that while he was what might be termed a contracting architect, that he knew absolutely nothing about this class of architecture. In fact, he assured me time after time that he did not. On the "outline" which was requested, I did the entire work without any assistance, and he did not even read it. I doubt he has read it yet…My connection with this work has been a pleasure[.] I have acquired some architectural knowledge, and am able to give more accurate descriptions.(46) |

Baxter—like many HABS and WPA employees, both male and female—took pride in her personal accomplishments and in the knowledge and skills gained even though the office experience left much to be desired. Indeed, the opportunity to gain experience and work skills was part of the WPA agenda. As J.T. Tubby, the district officer for Maine, noted—

Employment in the H.A.B.S. [sic] has meant…the development of a fair draftsman from inexperienced; in another case the bringing of an inexperienced draftsman to a large measure of responsibility and the maturing of high degree in draftsmanship…. The men in general have acquired or perfected a far more orderly system of measuring buildings. They are more observant and have gained an intimate knowledge of examples of Maine architecture.(47) |

From what is known of Virginia Thompson's experience as historian for the Virginia district office of HABS in Richmond, the independence that came with the position was also its own reward. Like Baxter, Thompson completed a large number of historical reports during her tenure, and she earned a reputation beyond HABS as a conscientious and thorough researcher. She corresponded frequently with other women and men outside HABS for original source material and other information on houses in Hanover, New Kent, King William, King and Queen, and other counties, including the house Scotchtown, the home of former First Lady Dolley Madison.(48) She also initiated several research trips on her own to museums, libraries, private homes, and historic sites.

One such trip—a reconnaissance visit to Fort Egypt and other extant defensive houses in western Page County built during the French and Indian War—resulted in kind words back to Virginia district officer Major Eugene Bradbury. "We are glad to cooperate with Miss Virginia Thompson," wrote Page county supervisor A.V. Moon, "for we feel that she is doing very good work."(49) Thompson was able to raise awareness of these structures back in the Richmond office, which eventually dispatched a field team to record three examples of this building type in the area.

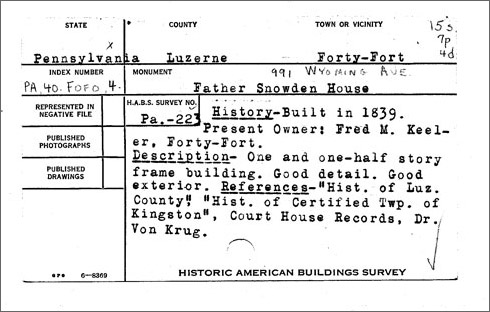

The Secretary as Historian

Bettie Toal Morrissey served as stenographer-secretary in the Northeastern (Wilkes-Barre) Pennsylvania office from 1936 to 1938.(50) She notified Washington that the office had "three draftsmen, one photographer, and myself, as stenographer," but she also maintained records, compiled weekly project status reports, wrote at least six historical reports, and became a project head for the Wilkes-Barre office in November 1938.(51)(Figure 8) A "non-relief case" like most women in the eyes of the WPA, Morrissey eventually took care of all the paperwork and history writing for the office, tasks of such great value to Ralph W. Lear, the deputy district officer and WPA supervisor, that he requested a non-relief exemption for Morrissey in 1937 to keep her on the payroll.(52) Most HABS district offices only requested exemptions to retain skilled architects and draftsmen.

|

Figure 8. Officially a secretary, Bettie Toal Morrissey in the Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, district office of HABS conducted historical research and typed up index cards like this one for the Shoemaker House in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

Morrissey also helped prioritize local buildings for survey and demonstrated a working knowledge of the architectural history of the region. She described the Kintner Mill, for instance, as one that "seems to be a good example of typical mill construction and design."(53) Unlike many of the secretaries who worked for HABS, she participated in recording projects, notifying Washington in the case of the Kintner Mill that "we are leaving Monday to begin measuring and photographing the building and I shall let you know, from time to time how the work is progressing."(54)

Few women are known to have worked as HABS project heads or assistant project heads in the 1930s. An assistant project head working in Morrissey's district in 1936 would have drawn a salary of $140 per month, whereas a skilled worker, which is generally how Morrissey and other stenographer-secretaries were classified, would have earned $85 per month. A professional historian would have earned $94 per month.(55)

The Volunteer

A stronger case may be made for the bridge between the amateur historic preservationists and volunteers in the HABS survey, those whose presence has precedent in the female-dominated historical preservation groups such as the Mount Vernon Ladies Association. Both groups, HABS and the volunteer preservation groups, were able to use their partnership to mutual advantage. The presence of HABS architects no doubt helped many such groups find funding as well as strengthened their push for preservation of historic architecture.

Most of the women associated with HABS during the 1930s served in an informal capacity as information providers and facilitators. This group included librarians, executive committee members of preservation societies, members of patriotic organizations and social networks, and history, genealogy, and architecture enthusiasts. Edith Stratton Kitt, the secretary of the Arizona Pioneers Society and a supporter of HABS in her state, later remarked in her autobiography that "clubwork"—

gives some women their only chance to develop themselves as individuals and to express themselves—through art, literature, service to others, etc. To women who do not need this outlet, it gives the chance to help others to get what they themselves have. And to both classes it gives an opportunity to make their concerted influence in the community.(56) |

Kitt admitted that she had often tailored her comments on history and nature conservation to fit the gender of her audience—

If I were speaking before a men's organization I tried to impress on them that it was not only patriotic but also good business to preserve Arizona scenic wonders and historic sites…. To the women's clubs I explained my ambitions for preservation of history in these words: "If we can ever so little get a great centralized collection of Arizonana established in Arizona, we will have done a great thing."(57) |

She tailored her communication with HABS men accordingly.

Kitt worked closely with the HABS team in Arizona, helping them establish contacts and identify recording projects. In 1937, she helped arrange a last-minute survey of the pillaged ruins of the San Cosme del Tucson Mission, which had fallen into the hands of "brick manufacture concerns" determined to recycle what remained of the buildings.(Figure 9) In a memo to Washington, Thomas Vint reported that—

Mrs. George H. Kitt, secretary of the Historical Society has obtained permission from the owners to do excavation work in and about the ruins for the sake of information that might be found. Mrs. Kitt is willing (I might say anxious) to turn this privilege over to the park service.(58) |

They succeeded only in producing a sketch plan and a photograph of the site for the survey.(59)

|

Figure 9. This 1937 photograph shows a part of the pillaged San Cosme del Tucson Mission in Pima County, Arizona, that volunteer Edith Stratton Kitt had called to HABS's attention. (John P. O'Neill, HABS photographer. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

Kitt's work with the Arizona Pioneer Society and her contacts with the HABS team involved far more than the title "secretary" might imply. One of the most influential early 20th-century preservationists and historians of the West, she remarked that the "title 'secretary' was erroneous, for I had to be not only the corresponding secretary but also the librarian, researcher, entertainer, welfare worker and father confessor all in one."(60) She inherited a—

society housed in a large room on the ground floor of the Tucsonian Hotel building (with) a book case with glass doors. In it were a few books on the west, some old school books, an illustrated edition of Dante's Inferno, the complete works of Sir Thomas More, and other classics.(61) |

But quickly she was "dreaming of what the Arizona Pioneer Historical Society might become…the great central repository of regional history of the State of Arizona."(62) Although she earned only a nominal amount, Kitt worked hard to raise the society's profile, improve its collection of written and oral histories, and eventually find a permanent home for the society at the University of Arizona in 1928.

In the spirit of that informal network of women that drove most preservation and historical societies, Kitt noted that—

the most effective helper I ever had was Mrs. Harold H. Royaltey, who for many years worked beside me as a volunteer. She always did whatever was necessary but took special delight in writing letters. She wrote hundreds of bright friendly letters to people all over the state—and in fact all over the country asking them for their historical treasures.(63) |

One of Kitt and Royaltey's correspondents was Frederick D. Nichols of HABS, to whom Kitt promised free access to the Pioneer Society's and her own "photographs and other data on the historic buildings of southern Arizona."(64) Kitt also led HABS through the society's elaborate social network of property owners and history enthusiasts, even arranging visits with her friends and associates.(65)

HABS district offices across the country relied on dedicated and influential women like Kitt for local contacts and news and information on the owners, locations, and conditions of historic buildings and sites. Many of them spoke out in support of the survey when its future seemed uncertain. Among those allies was Mrs. Arthur Wilmer, president of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. She told John P. O'Neill in January 1936 that—

The excellent work which the American Historic Building [sic] Survey has done makes the curtailment of this work seem a disaster to the nation. For the Survey not only preserves a record of the past but also gives a foundation upon which future architects can build… . At the next Board meeting of the Association of the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, of which I am president, I will ask the Association for an endorsement of a permanent Survey. Will you advise me to whom to address such resolutions?(66) |

The number of women who informally helped identify buildings in their communities or occasionally supplied genealogical and other historical information for HABS in the 1930s is impressive.(67) Many of them held jobs as librarians, though a number had mostly a personal or social interest in local heritage or a connection to historic buildings. This latter group of women had access to not only their family histories but also those of their husbands if they had married. Over time, many of them had acquired serious reputations as authorities on the history of their community's architecture. HABS architects were frequently directed to them as the first source for plans and information. North Carolina resident Elma Hairston gave HABS critical information and a copy of the floor plan of her mid-19th-century house, Cooleemee Plantation, near Mocksville.(68)

Librarians helped survey teams by providing information and access to historic documents and other records. They, too, had access to extensive networks and were interested in having local architecture documented for posterity. A librarian at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, told one HABS architect that he "might get some information from Miss I.E. Jerome, Providence Forge, Virginia. She is a descendant of the family that lived in the Providence Forge section for one hundred and fifty years."(69) Miss Shattuck of the Billings Library at the University of Vermont helped track down information on a place called "Grassmount" and referred HABS to H.F. Perkins, the director of the Fleming Museum, who was conducting an architectural survey in the area.(70) Mellie B. Pipes, the librarian for the Oregon Historical Society, proofread Jamieson Parker's manuscript for the outline of early Oregon architecture, providing both professional advice and informal information. "Only last week," she informed him, "I was told that the heavy snow of this winter had caused it (the Cray House) to collapse."(71)

Conclusion

Daniel Bluestone has claimed that "the professionalization of historic preservation in the 20th century brought with it the marginalization of women. The shift from women to men, from amateur to professional, paralleled a broader shift from patriotism to aesthetics as the basis for preservation."(72) This was not the case in the Historic American Buildings Survey, where women, despite cultural and governmental restrictions on employment, had rare opportunities to employ their administrative and creative skills.

The wide-ranging influence of women in HABS belied the conventional wisdom of the 1930s that women were best suited to do "domestic work."(73) The creativity and initiative of women preservationists like Kitt and Green, for instance, helped move the survey significantly forward since they frequently set the stage for what needed to be done. Historian Barbara Howe noted that women involved in the historic preservation movement in the United States actively "generated publicity, raised money, and bought and restored properties to save some of the nation's most treasured landmarks."(74)

The women who worked for and assisted the Historic American Buildings Survey during the 1930s proved that they could thrive in a male-dominated arena and make lasting contributions to society. Many of the female landscape architects associated with the Massachusetts Survey for example, went on to have solid careers in landscape architecture, while their survey drawings remain key documents in landscape architecture history. Indeed, there could be further work done concerning their unusual collaborative work model. Their influence is yet to be completely studied.

Though imperfect, the arrangements worked out between women and the Historic American Buildings Survey were mutually beneficial. Whereas women brought unique skills and sensibilities to the drafting and writing tables, HABS provided women professional opportunities that might have eluded them otherwise. A status report from the survey office in Oregon characterized the positive arrangement for one outnumbered woman succinctly—

Three non-relief men, one relief man and one relief woman are completing the drawings and transferring of field notes to final working drawings… . The workers have at all times been deeply interested in the work, and are grateful for the opportunity to study early Oregon architecture and history.(75) |

The women who worked for the Historic American Buildings Survey sought out new definitions for their work, covertly ignoring the restrictions and limitations. Women's suffrage had only been available for 13 years when HABS was established. Access to the public arena and access to professional male dominated professions were relatively new. These women were themselves pioneers, even if they may not have achieved startling breakthroughs in the male-dominated HABS.

Appendix

The following is a compilation of names of women currently known to have participated in the Historic American Buildings Survey between 1933 and 1941. The names are as they appear in the records of the Historic American Buildings Survey (Record Group 515) at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. The list includes names appearing on undated documents preserved among other records from the period.

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California Connecticut District of Columbia Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Iowa Kansas Kentucky Lousiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi |

Montana Nebraska New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island Tennessee Texas Vermont Virginia West Virginia Wisconsin |

About the Author

Amy Gilley teaches Film Studies and Theater at Northern Virginia Community College. This paper is the result of research conducted as a Cultural Resources Diversity Intern in the National Park Service in the summer of 2005.

Notes

1. A profile of historic preservation groups in Virginia, for instance, has shown that the leadership—mostly housewives or retired people—came from "the upper-middle-class white citizens with the wealth, education, and cultural background to devote time to historic preservation activities." Alice M. Bowsher, William T. Frazier, and Jerome R. Saroff, "Virginia Historic Districts Study," in Readings in Historic Preservation, eds. Norman Williams Jr., Edmund H. Kellogg, and Frank Gilbert (New Brunswick, NJ: Center For Urban Policy Research, 1983), 46.

In the early 20th century, the only schools in the northeastern United States offering design degrees for women were the Lowthorpe School and the Cambridge School for architecture. The latter generally required the applicant to have a four-year degree. Doris Cole, "The Education of Women Architects: A History of the Cambridge School," Architecture Plus (December 1973): 33. See also Marilyn Yalom, A History of the Wife (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2001), 388. Yalom notes that "higher education for women is a relatively recent phenomenon. The American women's colleges and most coed universities were a late-nineteenth century creation admitting only a very small percentage of females, mostly from the upper and middle classes."

2. Primary research documents, including personal correspondence, are stored in the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, MD (hereafter cited as NARA). These records are included in the WPA files as well as the HABS files, which are filed under each regional and state office.

3. Cole notes (p. 33) that—

Women, when educated, were educated with other women, and their contact was largely with their servants, children, and families; they did not have contact with the male hierarchies of corporations in a profession which depended largely upon personal contacts for commissions…. Women in independent practice usually had small offices and, as noted, had difficulty in attracting corporate clients; with the trend toward complexity, they were further pushed into the corner of domestic architecture. |

4. HABS Circular No. 1, the first in a series of bulletins that set down the rules and procedures for the early survey, stated that "every district officer must be selected carefully with reference to both executive ability and knowledge of measuring work through actual experience. He is in each case being nominated by the appropriate American Institute of Architects chapter and appointed by the Secretary of the Interior." HABS Circular No. 1, December 12, 1933, reproduced in William Claude Corkern Jr., "Architects, Preservationists, and the New Deal: The Historic American Buildings Survey, 1933-42" (Ph.D. dissertation, George Washington University, 1984), vol. 2.

5. Barbara J. Howe, "Women in the Nineteenth-Century Preservation Movement," in Restoring Women's History through Historic Preservation, ed. Gail Lee Dubrow and Jennifer B. Goodman (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 17.

6. John P. O'Neill to Thomas H. Atherton, July 30, 1935, Records of the Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) Division, Record Group 515 (RG 515), NARA.

7. Louise Rosenfield Noun, Iowa Women in the WPA (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1999), x.

8. Noun, 7.

9. Ellen Woodward, "Address before the Democratic Women's Regional Conference for Southeastern States," March 19, 1936, Records of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Record Group 69 (RG 69), NARA.

10. Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's administration, and one of the most politically influential women of her generation, felt that some job-seeking women were "a menace to society [and] a selfish shortsighted creature who ought to be ashamed of herself." Frances Perkins, as cited in Mimi Abramovitz, Regulating the Lives of Women: Social Welfare Policy from Colonial Times to the Present (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1996), 224.

11. Nancy E. Rose, Put to Work: Relief Programs in the Great Depression (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1994), 28, 30.

12. Phyllis Hamblur to Harry Hopkins, June 19, 1935, RG 69, NARA.

13. One exception was Annie Scott Baxter, a historian for the Erie, Pennsylvania, HABS office (see below), who appears in the rolls as a certified draftsman. According to her correspondence, she took a course in drafting to enhance her architectural research, but her unofficial status as "historian" might have been a way to hire her for less money. Annie Scott Baxter to John P. O'Neill, March 10, 1938, RG 515, NARA.

14. Irving Morrow, California district officer, to Roy W. Pilling, assistant administrator of the Emergency Relief Administration (ERA) in California, September 12, 1934, RG 515, NARA.

15. Henry Frost quoted in "The Education of Women Architects: A History of the Cambridge School," by Doris Cole, Architecture Plus (December 1973): 33.

16. Dorothy May Anderson, "Women's Breakthrough via the Cambridge School," Landscape Architecture 68 (March 1978): 147.

17. According to the Almanac of Architecture and Design (2004), only half the design schools in the United States in 1910 permitted women to enroll as architecture students. Although the percentage might have increased during the 1920s and early 1930s, it did not attain 100 percent by the mid-1930s. Almanac of Architecture and Design (Washington, DC: Greenway Communications, 2004).

18. Anderson, 148.

19. Anderson, 147. See also Jan Jennings, "Leila Ross Wilburn: Plan-Book Architect" (Woman's Art Journal 10 no. 1 [Spring-Summer 1989]: 12) in which Jennings notes that a "1912 builder's journal states that there seems no logical reason for the dearth of women architects because as 'draftsmen' they demonstrated 'exceptional artistic and constructive talents.'"

20. The Lowthorpe School's 1917 catalog notes that the school was dedicated to "the training of young women who desire to enter upon any of the many lines of work in life appropriate to women comprehended under the terms Landscape Architecture, landscape gardening and Horticulture." The curriculum focused on landscape design, with courses in drawing, botany, greenhouse work, surveying, and "engineering (such parts as have value to landscape work)," garden design, landscape design, and plant materials.

The rigorous coursework prepared students in the basic survey techniques used by HABS. A.F. Tripp noted—

In drafting…the study of local examples follows with measured drawings, sketch plans and reports, then the solution of original problems based on topographical surveys… . Survey and engineering include the principles of plain surveying, methods plotting to scale, use of the chain, tape, compass, level, staking out and setting grades. |

See A.F. Tripp, "Lowthorpe School of Landscape Architecture, Gardening and Horticulture for Women," Landscape Architecture (October 1912): 15-16.

Other schools soon followed the Lowthorpe model. The Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women opened in the Philadelphia suburb of Ambler in 1910. The Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape opened in 1915 in affiliation with Harvard University, which at the time did not admit women.

Lowthorpe changed its name to the Lowthorpe School of Landscape Architecture in 1929. The School merged with the Rhode Island School of Design in 1945, becoming a department within the Division of Planning.

21. Dorothy May Anderson, a graduate of the Lowthorpe School who went on to teach at the Cambridge School (see note above), wrote extensively about the Cambridge School, particularly its founding teacher, Harvard design professor Henry Frost. This author speculates that Frost's relationship with his students was similar to Mayall's relationship with his students at the Lowthorpe School. "Because they could not find offices to take them in," Anderson wrote, "our students got into the habit of accepting commissions as practitioners without the benefit of…invaluable office training. Whenever we could, those of us who had small offices used our own graduates as office assistants, but this took care of only a few of them." Dorothy May Anderson, Women, Design, and the Cambridge School (West Lafayette, IN: PDA Publishers, 1980), 18-19.

22. Maude D. Parlin to Frank Chouteau Brown, January 9, 1935, RG 515, NARA.

23. Webster and Rowell checked the measurements and drew four of the six sheets for the William Wheelwright Place project (Newburyport, MA; HABS No. MA-209), for example, while Mayall prepared the index card. In other cases, the roles were reversed. The documentation is available online at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.ma0669, accessed on April 4, 2008.

24. The documentation for the Lindens (HABS No. MA-2-33), Danvers, MA, is available online at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.ma0610, accessed on April 4, 2008. The Lindens has a strange history: The house itself was moved to Washington, DC, in 1934, severing it from its landscape and garden.

25. Despite this architectural expertise, Saunier appears on the employment rolls as "senior clerk."

26. The documentation of the Squire William Sever House (HABS No. MA-135) in Kingtson, MA, is available online at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.ma0872, accessed on April 4, 2008.

27. Frank Chouteau Brown to John P. O'Neill, October 26, 1937, RG 515, NARA. As for Mayall's dismissal, Brown writes—

Mayall was lecturing two afternoons a week at Lowthorpe School at Groton, and so obviously could not be in his office Tuesday afternoon, one of the days when the project was operating. His time sheet showed "7 Hours" that day which might have been given that evening, without doubt—as I know he worked many more days, as well as hours, than the minimum prescribed, just as I do!—but it had not been "sxplained" [sic] the time sheets, and so has been regarded as dereliction of duty, by the "higher ups" in WPA offices. |

28. Cole, "The Education of Women Architects: A History of the Cambridge School," 33.

29. Andrew L. Delehanty to Frank Chouteau Brown, September 10, 1936, RG 515, NARA.

30. Two historical reports written in 1937 bear Mayer's name: the Lansing-Pemberton House (HABS No. NY-3203; http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.ny0009) and the Old Homeopathic Hospital (Interiors) (HABS No. NY-6002; http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.ny0444). It is uncertain how many index cards and histories Mayer might have prepared because many of the documents produced by the Albany office are unsigned.

31. Andrew L. Delehanty to Frank Chouteau Brown, August 6, 1936, RG 515, NARA.

32. Andrew L. Delehanty to John P. O'Neill, September 19, 1936, RG 515, NARA.

33. Frank Chouteau Brown to John P. O'Neill, October 26, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

34. Frank Chouteau Brown to Andrew L. Delehanty, December 20, 1937, RG 515, NARA. Brown's inconsistencies raise interesting questions about his attitude towards women in HABS offices, not to mention his memory. He frequently signed his letters "Hastily yours."

35. Frank Chouteau Brown to John P. O'Neill, December 13, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

36. Helena Mayer to John P. O'Neill, December 6, 1936, RG 515, NARA.

37. Ibid.

38. Helena Mayer to Frank Chouteau Brown, March 8, 1938, RG 515, NARA. Mayer goes on to say—

Mr. Delehanty is very busy working on some maps for Senator Corning to go with the reports and as usual is in a mess trying to get them out, having postponed the time of delivery three times. I finished my reports a week ago but he asked me to stay a little longer and try to line up some more buildings and historic spots in Albany County for him. I have found the research work very interesting. |

39. Frank Chouteau Brown to John P. O'Neill, March 11, 1938, RG 515, NARA.

40. Helena Mayer to John P. O'Neill, January 11, 1938, RG 515, NARA.

41. Frank Chouteau Brown to Helena Mayer, April 7, 1938, RG 515, NARA. Mayer was not alone in her commitment to HABS. Many people demonstrated a high level of commitment, working extra hours and days without pay and often spending money out of pocket for expenses just to complete the documentation.

42. Frank Chouteau Brown to [John P. O'Neill], January 28, 1941, RG 515, NARA. Emphasis in the original.

43. Annie Scott Baxter, to John P. O'Neill, March 10, 1938, RG 515, NARA. These sewing projects, although classified as unskilled labor, required demanding work, with projects often set up as pseudo-factories. In Iowa Women of the WPA (p. 18), Noun notes that "There were a few five minute rest periods during the day, but no talking was allowed while working."

44. Annie Scott Baxter to John P. O'Neill, February 5, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

45. Howard Hicks to John P. O'Neill, January 27, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

46. Annie Scott Baxter to John P. O'Neill, February 5, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

47. J.T. Tubby to Frank Chouteau Brown, n.d., RG 515, NARA.

48. In a letter dated September 5, 1936, Thompson asks Mrs. A. P. Gray of West Point, Virginia, for information on houses in New Kent, King William, and King and Queen Counties. Many data sheets from surveys in these counties bear her name. Thompson also corresponded with Mrs. Harris of Ashland, Virginia, about original source material for Scotchtown, the home of Dolley Madison. In July 13, 1936, she received copies of pages "torn from a book kept by Miss Sallie Taylor," the present owner of Scotchtown.

49. W.A. Moon to Major Eugene Bradbury, September 24, 1936, RG 515, NARA.

50. Morrissey's predecessor, Minnie Searfoss, wrote index cards for projects but did not prepare the histories.

51. Bettie Toal Morrissey to John P. O'Neill, November 12, 1938, RG 515, NARA.

52. Non-relief worker status did not indicate personal wealth; rather it indicated that a person—for whatever reason—did not qualify for relief under WPA rules. Many women—including married women—ended up in the "non-relief" category because the WPA did not recognize them as heads of household even though they might have been single and living alone or responsible for the welfare of their family (children, siblings, or parents).

53. Bettie Toal Morrissey to John P. O'Neill, July 6, 1938, RG 515, NARA.

54. Ibid.

55. Generally speaking, HABS hiring practices did not follow the WPA's or any other hiring rules. The fluctuations in WPA requirements for relief and non-relief workers, sudden changes in budgets, and other factors meant that staff often got assigned to job categories that had little to do with the work they actually performed. In Erie, Pennsylvania, for instance, Annie Scott Baxter was listed as a certified draftsman on one form even though there is no evidence she produced a drawing; instead, she produced histories.

56. Emerson Oliver Stratton and Edith Stratton Kitt, Pioneering in Arizona; the Reminiscences of Emerson Oliver Stratton & Edith Stratton Kitt, ed. John Alexander Carroll (Tuscon, AZ: Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society, 1964), 149.

The Arizona Historical Society website gives a concise history of the organization—

The Arizona Society of Pioneers reincorporated in 1897 as the Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society (APHS). The restyled organization added two new membership categories: men who had resided in Arizona for thirty years and honorary members. For the first time, the Territorial Legislature appropriated funds—$3,000—to operate the organization for two years. Women slowly made their voices heard in the Society. Although an early invitation to form a "subordinate" women's auxiliary fell on deaf ears, a few women were accepted into the Society by 1913. In 1920 portraits of pioneer women were displayed at the Society's headquarters. Five years later APHS president Monte Mansfield asked Edith Stratton Kitt to serve as secretary, the Society's chief operating officer. Mrs. Kitt bridged the gap between social club and modern archive, organizing materials, recording reminiscences, and encouraging donations to the collections. |

For more information on the Arizona Historical Society "A Brief History of the Arizona Society of Pioneers and the Arizona Historical Society," http://www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/, accessed on March 12, 2008.

57. Ibid, 149.

58. Thomas Vint to John P. O'Neill, June 21, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

59. The documentation includes photocopies and a newspaper clipping describing the condition of the mission site.

60. Kitt, 50-1.

61. Kitt, 150.

62. Kitt, 155.

63. Kitt, 158.

64. Frederick D. Nichols to John P. O'Neill, August 14, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

65. See, for instance, Frederick D. Nichols to Edith Stratton Kitt, November 2, 1938 (RG 515, NARA), in which Nichols thanks Kitt for her help and asking if "Doctor Forbes or the other old gentleman that you and I called on has ever done anything about the prints that he was going to send us."

66. Mrs. Arthur Wilmer to John P. O'Neill, January 14, 1936, RG 515, NARA.

67. Other women who have been lost to history appear in this narrative. Blanche Chloe Grant, for example, an unofficial member of the Taos Artists Society, is mentioned by Helen Dorman, librarian of the Historical Society of Santa Fe, as one "who has written about Taos, may be able to help you. Her address is simply Taos, New Mexico." Grant was the author of The Taos Indians (1925), Taos Today (1925), and When Old Trails Were New: The Story of Taos (1934). An artist in the Taos art movement, Grant painted the murals on Taos Presbyterian Church in 1921.

Mayall's wife, Margaret Walker Mayall, who helped compile historical reports and take measurements for her husband's survey work, was an important astronomer, accomplished writer, and the president of American Association of Variable Stars Observers for 19 years.

68. The house was later measured and drawn for HABS in 1963 by students in the School of Design at North Carolina State College, now North Carolina State University. The house was situated on land that had been in the Hairston family since 1814. The documentation is available online at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.nc0022, accessed on April 4, 2008.

69. E.G. [Earl Gregg] Swem to Archie A. Biggs, May 3, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

70. No survey or history of Grassmount was ever produced.

71. Mellie B. Pipes to Jamieson Parker, April 9, 1937, RG 515, NARA.

72. Daniel Bluestone, "Academic In Tennis Shoes: Historic Preservation and the Academy," The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 58 no. 3 (September 1999): 302.

73. Cole, "The Education of Women Architects: A History of the Cambridge School," 31.

74. Barbara J. Howe, "Women in the Nineteenth-Century Preservation Movement," in Restoring Women's History Through Historic Preservation, ed. Gail Lee Dubrow and Jennifer B. Goodman (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 2003): 18.

75. HABS Oregon District Office, "Report," October 1936, RG 515, NARA.