Viewpoint

An Integrated Architecture for Effective Heritage Site Management Planning

by Dirk H.R. Spennemann

Heritage managers typically identify potential heritage sites and establish the public value of those places using predetermined cultural significance criteria. Current historic preservation theory maintains that this process ensures that important aspects of the past are identified, protected, and managed for the benefit of present and future generations.(1) The aim of heritage site management is to maintain these identified places intact and unchanged from their determined period (or periods) of significance to the extent feasible.

The integrity of such places, however, is impacted by a number of factors, from environmental decay to sudden impairment by natural or anthropogenic disasters, gradual or sudden impact by visitors and owners, and intentional damage through acts of vandalism, terrorism, or war. These threats to the integrity and survival of heritage sites can be restricted in their magnitude—and on occasion completely removed—through appropriate intervention.

Currently, each of the states in Australia uses its own planning processes and documents, all of which are based on the principles of the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter but go by different names.(2) In the state of New South Wales they are called conservation policies and conservation management plans;(3) in Victoria, conservation plans and maintenance plans;(4) in Queensland, conservation management plans and asset management plans;(5) in South Australia, conservation management plans and heritage asset management plans;(6) and in Western Australia, conservation plans.(7) In the United States, they are customarily called preservation plans.(8)

Conservation management plans typically contain a description of the extant fabric, a brief history, a statement of significance, and an array of conservation options usually recommended by the consultant completing the plan. Such documents seldom make any provisions for an expansion of management activities. Nor do they allow in their structure for easy review and revision. As a result, many conservation management plans, once completed, languish on the shelves. Because of the effort and resources involved in writing these plans, few incentives exist to revise them regularly in response to changing conditions.

Although generally viewed as site management plans, most conservation management plans fall short, addressing only certain management responsibilities. Among the most common lacunae are visitor and disaster management plans. Places that are open to the public may have interpretation plans, but their visitor management corollary is often lacking even though visitor use can result in damage through unintentional and intentional impact.(9) Disaster management is likewise largely absent. A review of conservation management plans in New South Wales and Victoria, for instance, showed that very few actually address issues of disaster management(10) even though heritage sites are prone to disaster impact.(11) This situation is due in part to attitudinal barriers among heritage professionals that discourage their formulation.(12) That review also uncovered extensive uncritical copying of text sections from other previously completed plans(13) and called attention to the complex language used in writing them.(14)

If heritage managers wish to manage these places effectively, they must acknowledge that the context in which a heritage site exists is subject to change. Political and economic conditions, public funding options, social expectations, and environmental conditions are among the variables that heritage managers must take into account. None of these variables changes at the same rate, however, and some parts of an original plan might require immediate or frequent updates whereas others might not. All too often, heritage managers keep plans well past their "use-by" or expiration dates. Without a strict regime of plan review, chances are good that conditions will develop that can adversely affect the integrity of a place.

An Integrated Architecture

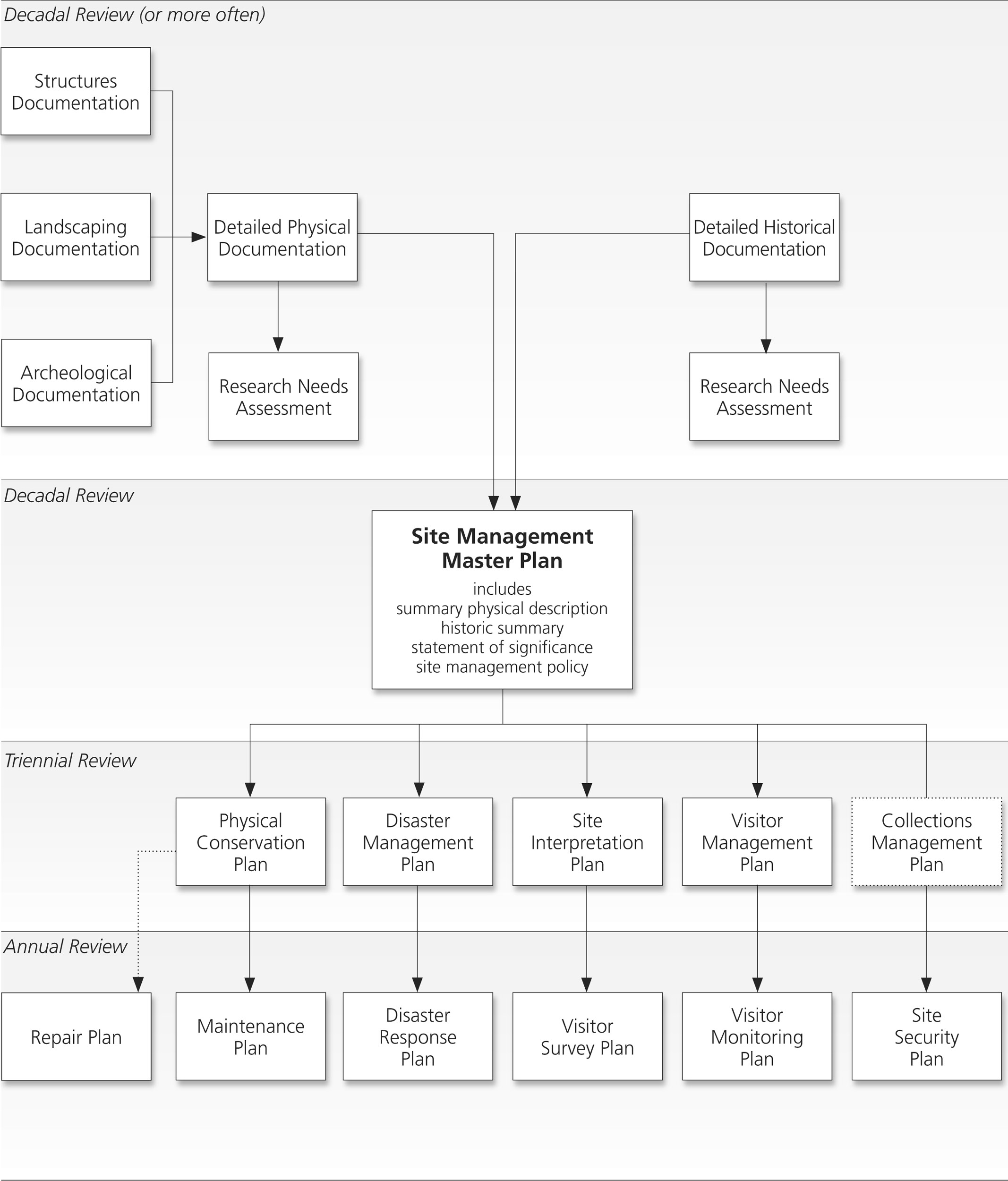

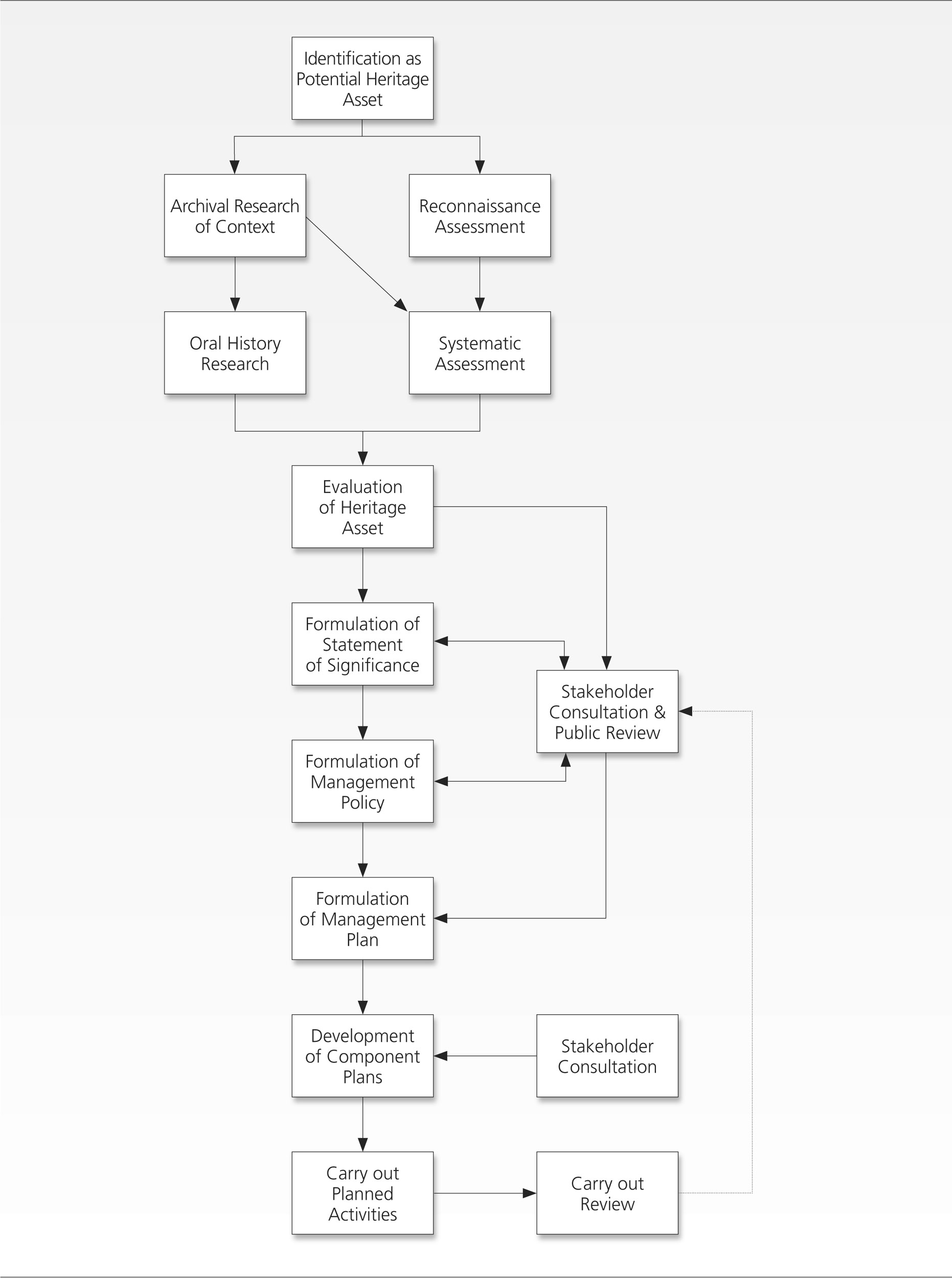

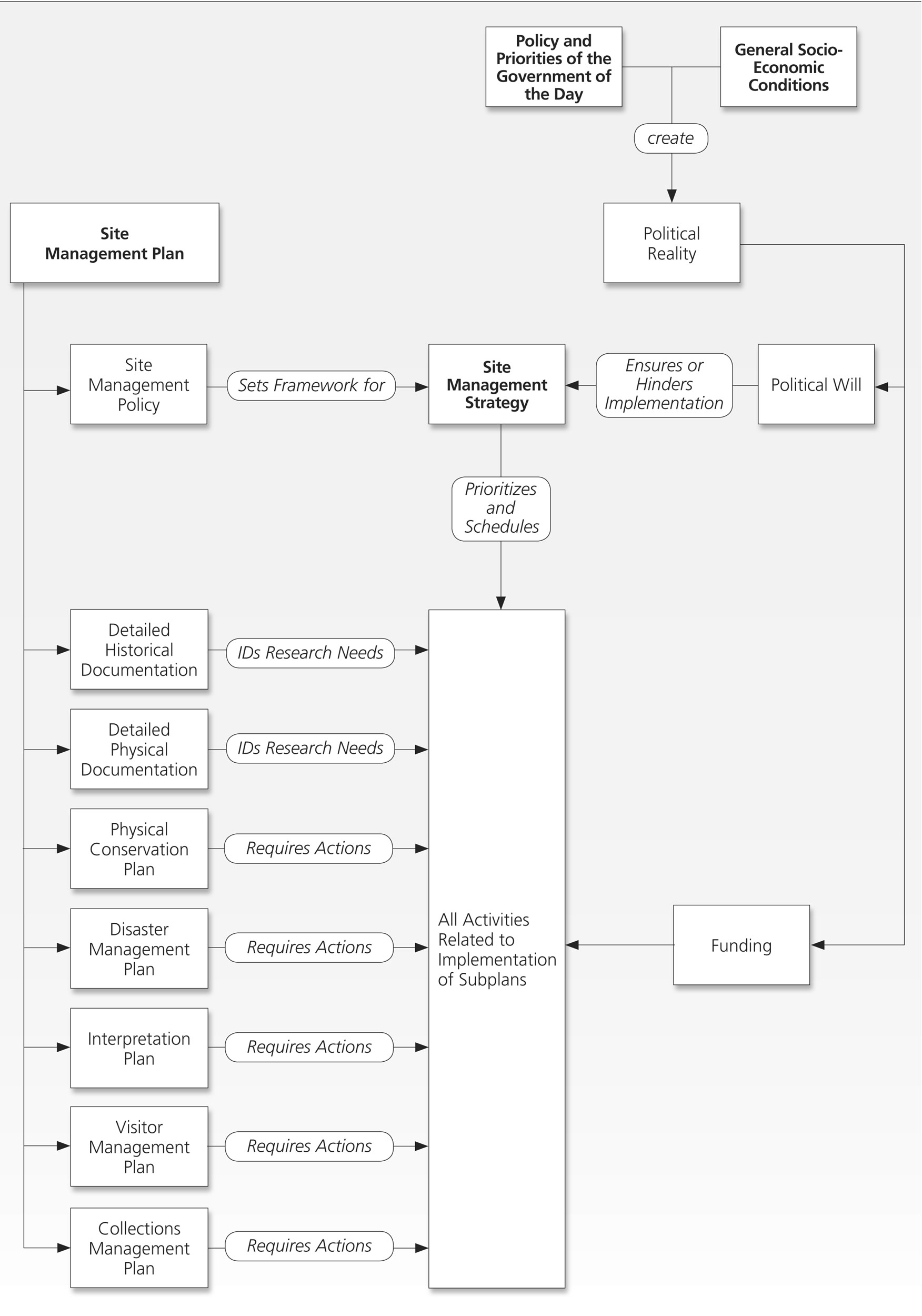

This paper proposes a model integrated architecture for a heritage site management plan that will provide site managers and staff with clear guidance on overarching aims and on-the-ground management action, along with objectively verifiable indicators of management success.(15) The model architecture in Figure 1 shows a correlation between a plan's effectiveness and its currency (that is to say, its up-to-dateness). It is based on the idea that heritage site management is a process that involves a number of steps and routines, namely identification, documentation, evaluation, formulation, implementation, and review. The flow chart in Figure 2 shows these steps in relation to public consultation.

|

Figure 1. This model integrated architecture for a heritage site management plan can provide clear guidance on overarching aims and on-the-ground management action. |

|

Figure 2. This flow chart shows the steps in the heritage site management process in relation to public consultation. |

Site Management Plan

The heritage site management plan is both hierarchical and modular and made up of an array of elements that are subject to periodic review depending on their place in the hierarchy. At the top of the hierarchy is the heritage site management master plan.

The master plan contains a brief physical description of the place, a concise contextual history, and a statement of significance. It includes a management policy that sets out the future use of the place, management objectives, and priorities in case of value conflict (for example, conservation versus access). It establishes conservation standards and priorities, and it provides for the development and periodic revision of components subject to the policy.

The master plan relies on in-depth documentation of the history and physical fabric of a place for direction. This documentation may take the form of a single document or a set of subdocuments on the structures, landscapes, and archeology that define the place. The master plan abstracts pertinent facts from these documents, to which it refers readers for more information. In the model architecture, each document has a subordinate research needs assessment that spells out the shortcomings in the knowledge base and identifies corrective measures. The history and physical fabric documents are subject to the same review cycle as the site management master plan, although they might be revised in the interim if new discoveries add substantially to the knowledge required for making management decisions.

The management objectives articulated in the site management policy will determine the nature and number of component plans. At a minimum, each place should have a physical conservation plan and a disaster management plan. If the site management policy encourages or requires visitation, then site interpretation and visitor management plans are in order. If the place involves moveable objects, then a collections management plan is imperative. That plan should contain acquisitions and curatorial policies spelling out how and whether objects are to be obtained, exhibited, stored, conserved, and made available for study. At the very least, such places should have a security plan even if the place is not accessible to the public.

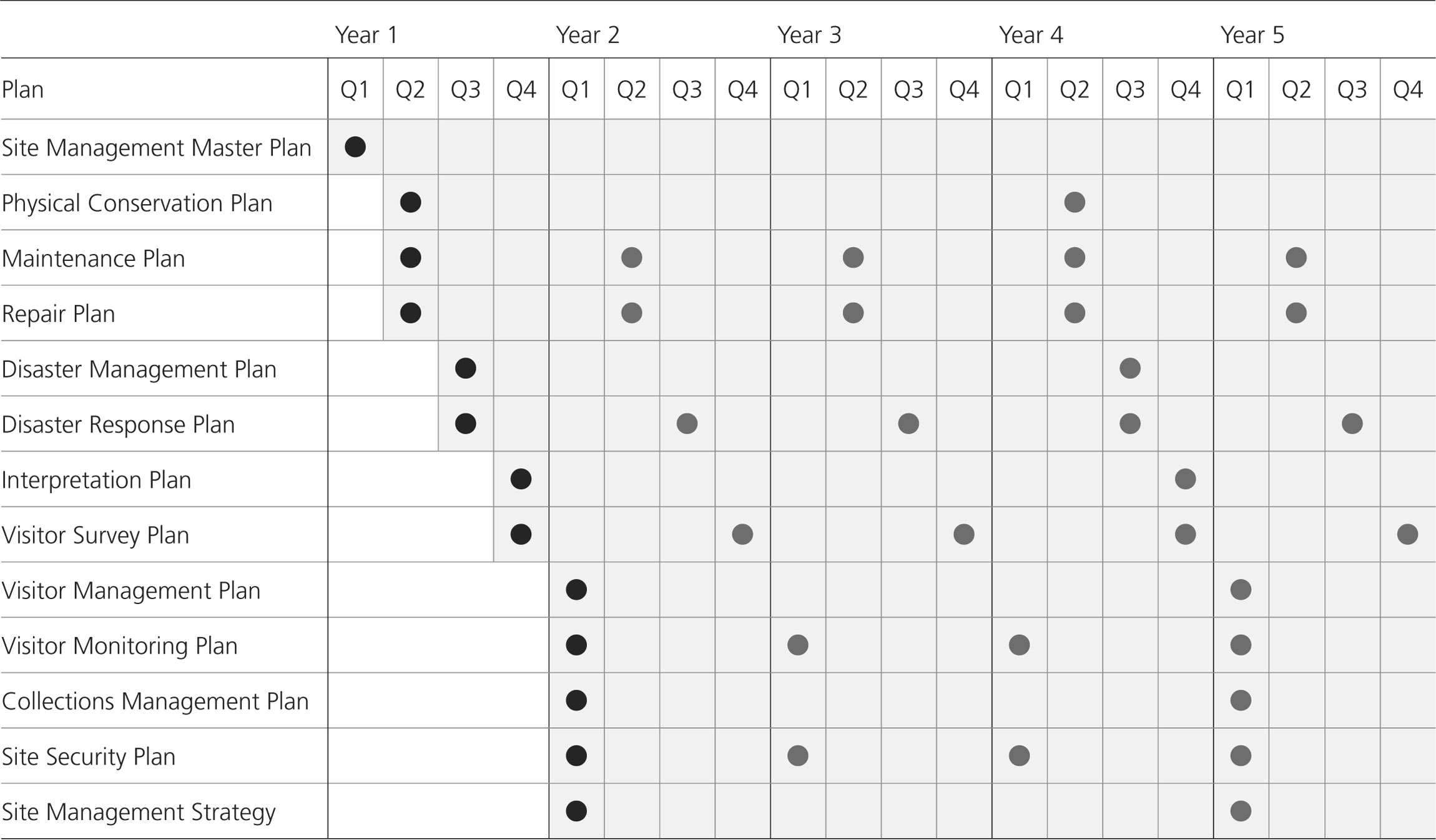

The component plans are based on assumptions that will change over time because of evolving social and environmental conditions. The triennial review and revision cycle for a component plan proposed in the model architecture strikes a reasonable balance between the urge to stay current and the need to keep planning in check. Figure 3 shows a development, implementation, and review sequence for a hypothetical site management plan based on the model.

|

Figure 3. The heritage site management planning process begins with a master plan, followed by physical conservation and other component and implementation plans. |

The component plans in this model include brief implementation plan documents. The physical conservation plan features a maintenance plan that spells out, for example, how often the gutters should be cleaned, or how often the place should be checked for mud wasp infestation. A separate repair plan sets out the nature and specifications of work related to major repair needs that are identified in the physical conservation plan. The disaster plan includes a response plan that a heritage site manager and staff will consult and implement when necessary. As another example, the visitor management plan has a subordinate visitor monitoring plan for assessing whether visitor behavior and impact turn out as forecast.

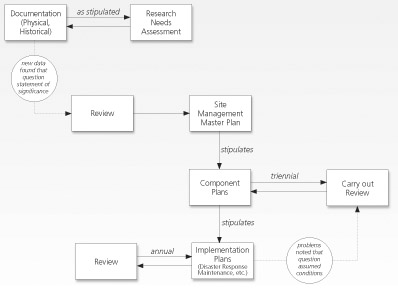

In the scenario, these implementation plan documents are subject to an annual review. The component plans should have a mechanism in place for an unscheduled review in the event that implementation results in some unexpected and potentially counterproductive impacts. Figure 4 shows how the review of the implementation plan and other documents can affect the overall site management plan.

|

Figure 4. The heritage site management master plan and component and implementation plans are subject to periodic review. |

Basic Outline of a Site Management Master Plan

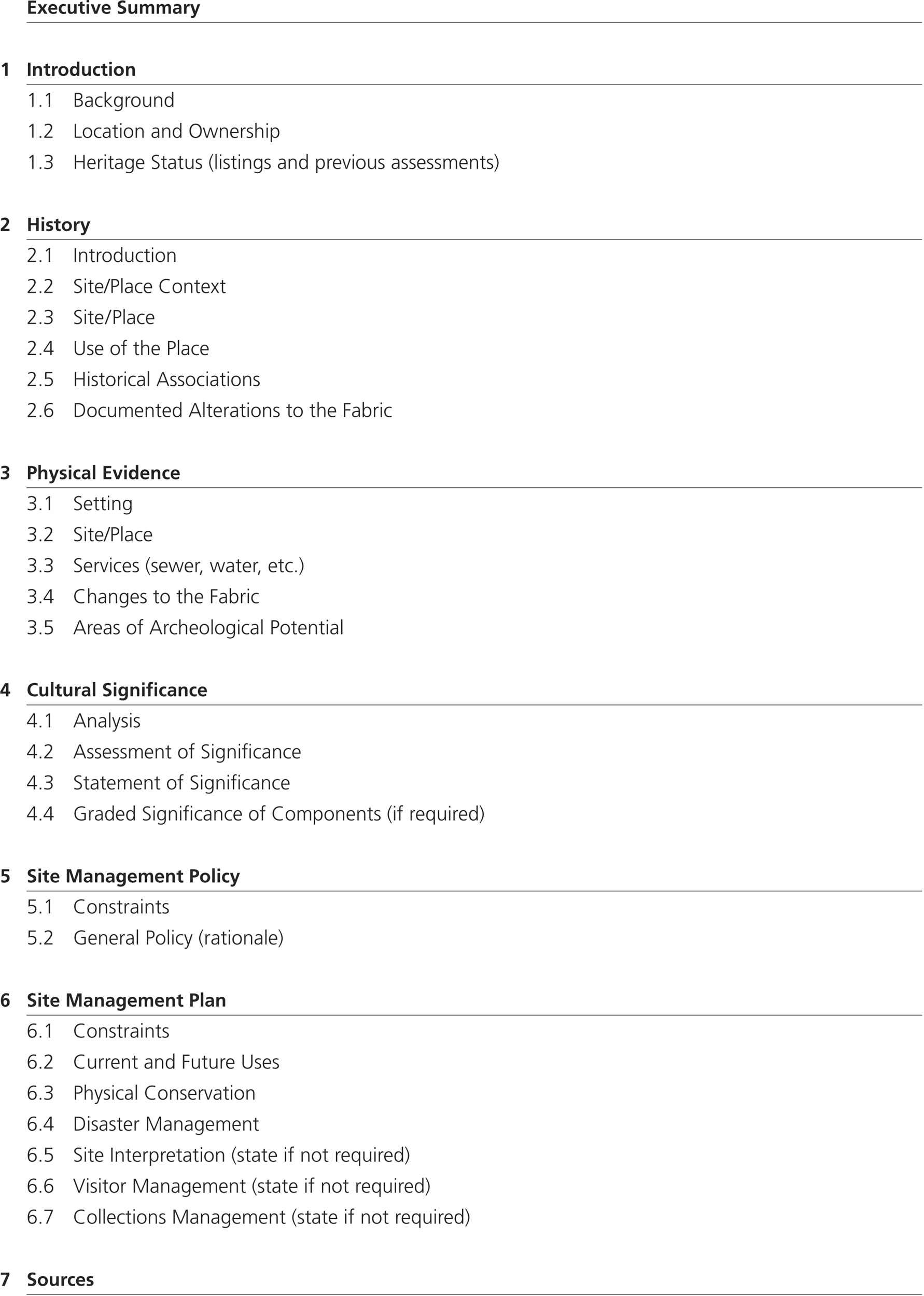

Figure 5 shows the outline of a site management master plan organized according to the model.

|

Figure 5. This outline for a master plan is based on the model integrated architecture for a heritage site management plan. |

Section 1 of the model consists of summary information. Sections 2 and 3 include extracts from history studies and physical fabric documents, along with references. Section 4 sets out the statement of significance. Section 5 spells out the site management policy that governs all future management and use. It involves specific management objectives and priorities. In case of value or management priority conflicts, it provides guidance on how to solve them. Section 5 also sets out the constraints on the management of the place, which might involve staffing, training, access, or use issues. Current and future uses are described next. Together with the policy, they provide the practical framework in which the place is to be managed.

The next sections consist of general comments and critical information on physical conservation and disaster preparedness extracted from the related component plans. Interpretation, visitor management, and security plans are essential if the site is to be accessible to visitors.(16) If the site contains valuable moveable objects, then collections management and security plans are in order even if the site is not open to the public.

Strategic Plan

The strategic plan represented in Figure 6 collates all the actions identified in the component plans and prioritizes them based on economic and political realities. The strategic plan looks at all aspects of management, including capacity building. Each action included in the strategic plan should have a specific launch and completion date, along with objective and verifiable performance indicators. Heritage site managers should review the strategic plan halfway through the plan cycle to ensure that their planning assumptions (funding levels, for example) and performance goals are still valid. Typically, a strategic plan's life cycle parallels public funding and political cycles.

|

Figure 6. The heritage site management strategy takes economic and other factors into account. |

Outlook

Using this model integrated architecture, heritage site managers can ensure that the cultural significance of a place can be maintained and that all impacts are controlled or minimized. Its modular approach acknowledges that only parts of the plan may require revision at any point in time, which will help ensure that the plan remains current and can be implemented. There is nothing magical about managing heritage sites for people to enjoy: It is just a matter of adequate and diligent planning.

About the Author

Dirk H.R. Spennemann, Ph.D., is an associate professor in cultural heritage management at Charles Sturt University in Albury, Australia.

Notes

1. William J. Murtagh, Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 1997); Michael Pearson and Sharon Sullivan, Looking After Heritage Places (Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 1995); Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Altruism and the Future of Historic Preservation," CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship, forthcoming.

2. Charter for the Conservation of Cultural Significance (The Burra Charter) (Canberra: Australia ICOMOS, Inc., 2000), http://www.icomos.org/australia/burra.html, accessed March 3, 2007; see also Guidelines to the Burra Charter: Cultural Significance, Conservation Policy, and Undertaking Studies and Reports (Canberra: Australia ICOMOS, Inc., 2000); Peter Marquis-Kyle and Meredith Walker, The Illustrated Burra Charter: Making Good Practices for Heritage Places (Burwood: Australia ICOMOS, Inc., 2004); Australian Historic Themes: A Framework for Use in Heritage Assessment and Management (Canberra: Australian Heritage Commission, 2001), http://www.ahc.gov.au/publications/generalpubs/framework/index.html, accessed March 16, 2007.

3. Guidelines on Conservation Management Plans and Other Management Documents (Sydney, Australia: New South Wales Heritage Office and New South Wales Department of Urban Affairs and Planning, 2002).

4. Preparing a Maintenance Plan (Melbourne, Australia: Heritage Victoria, 2001); Conservation Plan Standard Brief (Melbourne, Australia: Heritage Victoria, 2003).

5. Heritage Guidelines (Brisbane, Australia: Queensland Department of Public Works, 2003).

6. "Guidelines to Approaches for Conserving Heritage Places," Heritage Information Leaflet 1 no. 2; "Planning for Conservation Management," Heritage Information Leaflet 1 no. 3; and Model Brief for the Preparation of Conservation Plans (Adelaide: South Australia Department for Environment and Heritage, 2006).

7. Conservation Plans: A Standard Brief for Consultants (Perth: Heritage Council of Western Australia, 2002).

8. Draft Principles of Preservation Planning: Guidance for Local, State, Tribal, and Federal Preservation Planning Efforts (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2000).

9. "Visitors and their Impact: Protecting Heritage Ecotourism Places from their Clientele," in Cultural Interpretation of Heritage Sites in the Pacific, ed. Dirk H.R. Spennemann and Neal Putt (Suva, Fiji: Pacific Islands Museums Association/Association des Musées des Îles du Pacifique, 2001), 187-228.

10. Dirk H. R. Spennemann, "Risk Assessments in Heritage Planning in Victoria and New South Wales: A Survey of the Status Quo," Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 12 no. 2 (2005): 89-96.

11. Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Cultural Heritage Conservation During Emergency Management: Luxury or Necessity?" International Journal of Public Administration 22 no. 1 (1999): 745-804; Kristy Graham and Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Heritage Managers and Their Attitudes Towards Disaster Management for Cultural Heritage Resources in New South Wales, Australia," International Journal of Emergency Management 3 no. 2/3 (2006): 215-237.

12. Dirk H.R. Spennemann and David W. Look, "From Conflict to Dialogue, From Dialogue to Cooperation, From Cooperation to Preservation," in Disaster Management Programs for Historic Sites, ed. Dirk H.R. Spennemann and David W. Look (San Francisco, CA, and Albury, New South Wales, Australia: Association for Preservation Technology and Charles Sturt University, 1998), 175-188; Dirk H.R. Spennemann and Kristy Graham, "The Importance of Heritage Preservation in Natural Disaster Situations," International Journal of Risk Assessment and Management 7 no. 6/7, 993-1001.

13. Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "Risk Assessments in Heritage Planning in Victoria, Volume I: A Rapid Survey of the Conservation Management Plans Written in 1997-2002," Johnstone Centre Report 185 (Albury, Australia: Charles Sturt University, 2003); Prue Laidlaw, Catherine Allen, and Dirk H.R. Spennemann, "The Practice of Boilerplating in the Planning Process in Australia: An Examination of Bushfire Management Plans in New South Wales," submitted.

14. Prue Laidlaw, Dirk H.R. Spennemann, and Catherine Allen, "No Time to De(con)struct: The Accessibility of Bush Fire Risk Management Plans in New South Wales, Australia," Australian Journal of Emergency Management 22 no. 1, 5-17.

15. This plan was first formulated in 2004. Dirk H.R. Spennemann, Heritage Site Management: Distance Education Study Package (Wagga Wagga, Australia: Charles Sturt University, 2004).

16. A site management plan should include all headings as placeholders even if not applicable.