Article

Frances Benjamin Johnston's Legacy in Black and White

by Maria Ausherman

Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952) was one of the first American photographers to achieve a successful career in photography.(1)(Figure 1) She published and lectured extensively, exhibited her photographs nationwide, organized several large comprehensive photographic surveys of historic buildings and sites, and helped establish architectural documentation standards at a time when there were few professional opportunities for women outside the home. Trained as an artist like most early photographers, Johnston believed that photography rivaled painting as an art form and encouraged others interested in the medium to "learn early the immense difference between the photograph that is merely a photograph, and that which is also a picture."(2) She placed equal emphasis on composition, lighting, and subject matter. Revered as a pivotal figure in the pictorial photography movement, she believed that the best art always imitated the effects of nature on the eye, and that the task of the photographer was not any different than that of any other artist.(3)

|

Figure 1. This undated portrait of Frances Benjamin Johnston and her view camera captured the photographer in her prime. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

Over the course of more than six decades, Johnston photographed countless designed and cultural landscapes, seascapes, historic buildings and towns, international expositions, public events, celebrity portraits, and still life arrangements for institutional sponsors and corporate and individual clients. She understood the importance of detailed documentation, and, unlike many of her contemporaries, who seemed more concerned with impressions or truths beyond appearances, she placed a high priority on the accurate depiction of her subjects.

At the same time, she endeavored to give meaning to her photographs and made use of the suggestive powers inherent in photography to convey a social message. She was strongly committed to the preservation of historic buildings and sites and a variety of social issues. The camera enabled her to express her opinions subtly through images and motivate her audience to action when words alone seemed inappropriate or insufficient.

Johnston's personal material legacy, a lifetime of illustrated articles, books, correspondence, and thousands of photographic plates, negatives, and prints at the Library of Congress, rivals that of institutions like the early Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS; 1933-present) and the Farm Security Administration (FSA; 1935-1942), two federal work relief programs that documented American architecture and the American scene in photographs and other media during the Great Depression. Johnston participated in the HABS program, maintaining contact, working side by side, and exchanging information with HABS photographers and architects in the spirit of common cause. The documentation she produced in partnership with historical and patriotic societies, municipalities, state universities, museums, and federal agencies and programs, including the Library of Congress and HABS, endures as evidence of her genuine interest in the nation's architectural heritage and concern for its preservation.

Artist, Journalist, Photographer

Johnston was born January 15, 1864, in Grafton, West Virginia, a small Appalachian mountain town and an important rail junction for timber transportation during the Civil War.(4) Raised in Rochester, New York, where her maternal grandmother lived, the family moved some time before 1875 from Rochester to Washington, DC, where her father worked for the United States Treasury Department and her mother worked as a political journalist. Her parents and especially her aunt, Cornelia Hagan, supported her emotionally, and at times financially, throughout her life. Raised in an atmosphere of privilege that included early education in her home and additional studies in a Washington, DC, private school, Johnston graduated from Notre Dame Academy, a religious school for women at Govanstown (now part of Baltimore), Maryland. At her request, her parents sent her to Paris, France, to study drawing and painting at the Académie Julian, a well-known school for international students and one of few European academies open to women at that time.(5)

Johnston studied at the Académie Julian from 1883 to 1885. Her studio teachers, notably the French Academic painters Adolphe William Bouguereau (1825-1905), Gustave Boulanger (1824-1888), and Jules-Joseph Lefebvre (1836-1911), tended toward traditional subject matter, which carried over into the academy curriculum. Johnston herself was particularly proud of her formal art training. Like other American artists who had studied in Paris, she enjoyed a certain amount of prestige in the United States over non-Parisian trained artists of her generation and became part of an elite network that later helped advance her career.

Upon her return to Washington, Johnston joined the Art Students' League, a membership-based organization for artists in the national capital region.(6) She made the league her second home, maintaining a studio space, attending lectures, teaching classes, and playing an active role in the business of the organization.(7) She also studied art at the Corcoran School of Art and frequented the Smithsonian Institution. She later admitted that it was during her time with the league when she realized that her heart was neither in painting nor sketching but rather in journalism and photography.(8)

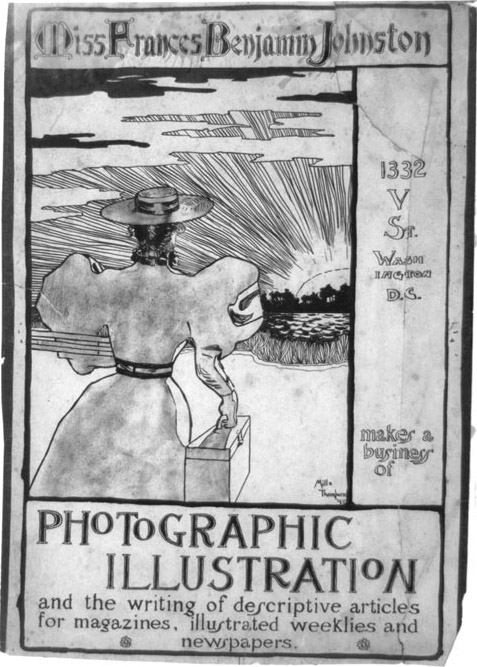

Johnston began her journalism career in the mid 1880s with a series of short newspaper and magazine articles—often called "sketches"—that she illustrated with pen-and-ink drawings.(9) (Figure 2) Around 1887, she asked inventor, businessman, and family friend from Rochester, George Eastman, for a camera to use for her journalistic pieces. Eastman responded by sending her one of the world's first roll-film Eastman-Kodak cameras. A dramatic improvement over earlier, heavier sheet-film cameras and ideally suited for press photography, the compact and lightweight Kodak roll-film camera stored enough film for approximately 100 images.(10) Johnston quickly turned to the camera and away from pen and ink for illustrating her magazine articles.

About the same time, Johnston started studying photography at the Smithsonian under the direction of pioneer photographer, scientist, and archivist, Thomas William Smillie. That contact resulted in a lifelong friendship and several important commissions for the Smithsonian, the United States Fish Commission (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the U. S. Navy, and the 106-acre National Zoological Park (the National Zoo) in Rock Creek Park in Washington.(11)

Johnston's first major photo-illustrated article appeared in two parts in Demorest's Family Magazine in 1889. Entitled "Uncle Sam's Money," the article described currency production in the United States and featured photographs and a series of engravings showing the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, DC, and the steps in the process of producing coins and paper money.(12) This commission quickly led to several others for the magazine, including an illustrated feature on the White House, a series on the homes of the members of the 51st United States Congress and President Benjamin Harrison's administration, photojournalistic essays on the Kohinoor coal mines in Pennsylvania, and an illustrated travel piece on Mammoth Cave (now Mammoth Cave National Park) in Kentucky.(13)(Figures 3-4) During this time, Johnston also accepted an appointment as one of the official photographers of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.(14)(Figure 5)

|

Figure 3. This 1890 photograph of the State Dining Room in the White House was among Johnston’s photos for Demorest’s Family Magazine. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

|

Figure 4. Johnston photographed these "breaker boys" at the Kohinoor Mine in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, in 1891. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

|

Figure 5. Johnston took this photograph of the Palace of Mechanic Arts at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

Shortly after her entry into photojournalism, Johnston established a professional connection with George Grantham Bain, founder of the Bain News Service (also known as Bain's Correspondence Bureau), the first photographic news service or news picture agency in the United States. The syndicate furnished articles and photographs to more than 14 major newspapers nationwide, including the New York Sun, the Philadelphia Times, and the Kansas City Times. Early on, Johnston and Bain collaborated on a series of articles for Cosmopolitan magazine, and by 1893 Bain was acting as her agent. That professional relationship, which lasted until around 1910, landed Johnston many photographic commissions.(15)

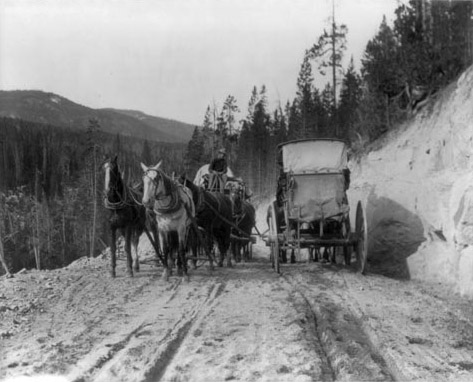

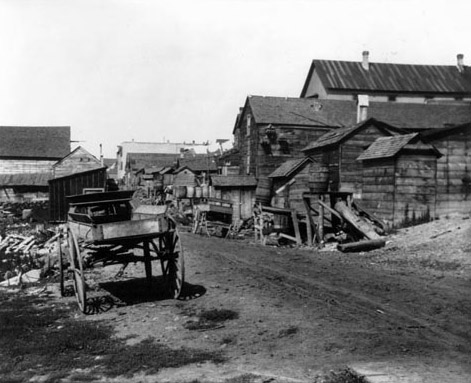

Johnston's photographs, letters, and other documents reveal that she was extremely busy completing freelance projects across the country during the 1890s and early 1900s. She traveled to Chicago for the Exposition, for instance; to Wyoming to photograph Yellowstone National Park; to central Pennsylvania to document the Kohinoor coal mines; and to northern Minnesota to record the open pit iron mining operations in the Mesabi Range owned by the Carnegie Steel Company.(Figures 6-7) Most of her income during this period actually came from portrait commissions from members of Washington society. Through family connections she gained access to high-level government officials and their families. Her social connections were not lost on magazine editors, who frequently looked to her for portraits of major figures and other photographic work. Over the course of her career, she knew and photographed five U.S. Presidents.(16)(Figure 8)

|

Figure 6. Johnston photographed these two stagecoaches passing on Mountain Road in Yellowstone National Park in 1903. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

|

Figure 7. Johnston's photograph of buildings near the Carnegie Corporation's open pit mining operations in Minnesota's Mesabi Range dates from 1903. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

Johnston later admitted that she lost interest in portraiture once it had become commercial and stressful. She felt the hectic pace required to meet business demands and the limited interests of the general public threatened to compromise her art. A European tour in 1905 also influenced her decision by awakening her traditional aesthetic sensibilities and interest in architecture and designed landscapes. With the daily newspaper staff ever ready to make frequent editorial decisions for greater public appeal, and at the urging of architects John Carrère, Charles Follen McKim, and others who increasingly turned to her for photographs of their recently completed buildings and country estates, she decided to move to New York City where she could have greater artistic control and pursue other outlets for her art.(17)

Johnston and business partner and close friend, Mattie Edwards Hewitt, opened a photographic studio at 536 Fifth Avenue in 1913, and for the next four years they collaborated on architectural and garden photography projects. Johnston herself explained that she "wanted to specialize and Mrs. Hewitt wanted to help. We looked over the field and decided that there was great work to be done in photographing beautiful homes."(18) Their list of clients included the architects and firms of Carrère and Hastings, McKim, Mead and White, John Russell Pope, Charles A. Platt, and Cass Gilbert. They also did work for the City National Bank and the North German Lloyd Company, a major transatlantic steamship line. Through it all, their main emphasis remained country estates, many owned by clients or friends of clients such as John Pierpont Morgan, John J. Astor, Edward T. Stotesbury, Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney, and other members of society.(Figure 9)

Johnston's decision to move to New York also had to do with the city's emergence as the commercial and artistic center of American photography. She and Hewitt opened their studio a few blocks from Alfred Stieglitz's fine art photography gallery, Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession (later known simply as 291), and photojournalist Jessie Tarbox Beals's studio. Other photographers with portrait studios on Fifth Avenue included Gertrude Kasebier (with whom Johnston had traveled to Europe in 1905) and Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr., a leader of the pictorial movement in photography.(19) As one critic of the time observed, "There is a glamour over Fifth Avenue, New York, such as is over no other photographic center in America."(20)

During this partnership, Johnston acquired knowledge of horticulture and the history and folklore of gardens, and she developed a series of lectures on American gardens that she illustrated with lantern slides made from her own photographs. She also began to build her own collection of garden books, later claiming to "know the garden and flower shelf of every secondhand book store in the country."(21) Her collection of more than 100 books included works by British landscape gardeners Gertrude Jekyll and Sir Humphry Repton, British architects Edwin L. Lutyens and H. Inigo Triggs, the American landscape architect Platt, and noted author and critic Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer. By 1920, she was giving slide lectures to garden clubs and other civic improvement organizations across the United States.

Johnston returned to Europe in 1925 for a seven-month stay, during which time she photographed, in her words, "mainly the Spanish castles, Italian palaces and French chateaux of the Vanderbilts, Astors, Whitneys and Goulds"—all of whom had made their fortunes in the United States and owned estates in Europe.(22) Back in the United States, she exhibited 150 prints of her European photographs in a private show entitled "In Old World Gardens" at Ferargil Galleries on East 57th Street and later at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden. She returned to lecturing and publishing regularly in Munsey's, Vogue, Town and Country, Arts and Decoration, House Beautiful, Studio, and other leading art and women's magazines of the period.(23)

Focus on Southern Architecture

In the summer of 1926, Johnston visited a number of places in the eastern United States as part of an assignment to photograph gardens for Town and Country magazine. On this trip, she became deeply interested in the colonial architecture of the South. "It was though my travels after gardens," she later explained, "that I noticed the fine old houses which figured so importantly in colonial history and which are falling to wrack and ruin unhonored and unsung."(24)

During a stop in Fredericksburg, Virginia, she met Helen Devore, who commissioned her to photograph Chatham Manor, Devore's recently restored estate just outside the city limits.(25) Johnston expanded this single commission from Devore into a more extensive photographic survey of the historic architecture of Fredericksburg and the old Falmouth region of Northern Virginia. The survey took three summers to complete and resulted in a small exhibit at the Fredericksburg Town Hall.(26)(Figure 10)

|

Figure 10. Johnston photographed these warehouses at 301-307 Sophia Street in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1927 as part of her area survey. (Courtesy of Gary Stanton, University of Mary Washington.) |

One of the first comprehensive photographic surveys of the historic architecture of a single American town, Johnston's Fredericksburg survey led to other Virginia projects. In the late 1920s, she collaborated with author Henry Irving Brock on the book, Colonial Churches in Virginia (1930).(27) She also helped raise funds for improvements to the grounds at Stratford, Civil War Confederate general Robert E. Lee's birthplace, later photographing the house for the architectural historian Fiske Kimball at the University of Virginia.

Eager to promote and continue her Virginia work, Johnston contacted Lester B. Holland, chair of Fine Arts at the Library of Congress and chair of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Committee on Preservation of Historic Buildings, and Edmund S. Campbell, head of the Department of Architecture at the University of Virginia, in 1932 with the hope that they might petition the Carnegie Corporation of New York, a philanthropic trust founded by the 19th-century industrialist Andrew Carnegie to "promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding," to fund a more extensive photographic survey of historic buildings in the commonwealth.(28) Holland and Campbell, in turn, submitted a successful joint proposal to the corporation for funding for six more months of Virginia fieldwork and new study prints for the University's School of Fine Arts.(29)

By the time Johnston began this first round of Carnegie-funded fieldwork in Virginia in 1933, she had already taken more than 1,000 views of buildings in 67 Virginia counties and had established a solid survey methodology.(30) She researched each region, spent considerable time studying published books on local history and architecture, and consulted maps and unpublished documents. She routinely contacted local historians and architects, homeowners, and community leaders for information. She searched through deeds and old plats for dates and chains of title. She used U.S. Geological Survey quadrangle maps for orientation and kept meticulous photographic logs. In Virginia alone, she traveled several thousands of miles. Upon the completion of the Carnegie survey of Virginia architecture in 1936, she exhibited a selection of the 2,500 photographs she had taken over the course of the project at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond.(31)

Johnston drew inspiration for her photographic surveys from architectural publications, notably the White Pine series of architectural monographs published by Weyerhauser Mills of Minnesota.(32) Like contemporary books such as The Dwelling Houses of Charleston, South Carolina by Alice Ravenel, Huger Smith, and Daniel Elliott (1917), and Fiske Kimball's Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic (1922), the series interspersed descriptive text, plans, elevations, perspective views, and evocative sketches of selected historic buildings, along with signature architectural details.(33) Johnston was particularly impressed that the White Pine Series publishers acknowledged architectural photographers as "craftsmen, who made this publication unrivaled in distinction."(34) She owned her own copies of the series and frequently referred to them when explaining to others the nature of her documentary work.

Johnston followed up her statewide survey of Virginia with smaller scale projects, including one in St. Augustine, Florida, and a larger Carnegie-funded survey of North Carolina. She took nearly 400 photographs of historic buildings along the Carolina coast and, with money from another Carnegie grant, doubled the number of photos and made 180 prints for an exhibit at the University of North Carolina art museum in Chapel Hill.(Figure 11) The following year, North Carolina textile mill owner Charles Cannon and his wife commissioned 200 photographs of historic buildings in western North Carolina to round out the survey.(35)

By September 1938, Johnston had visited more than 40 counties across the state. With nearly 800 negatives in hand, she approached the American Council of Learned Societies and the Colonial Dames of America with a book project.(36) Published in 1941 by the University of North Carolina Press, The Early Architecture of North Carolina featured more than 240 of Johnston's views, along with text she had co-authored with HABS historian Thomas T. Waterman, who independently had spent a fair amount of time in North Carolina photographing historic buildings for HABS.(37)

Of all her publications, Johnston considered the North Carolina book to be her "very own."(38) She oversaw the research, finances, writing, photography, design, and publication. For his part, Waterman contributed information from HABS field notes and other documentation.

At the invitation of Lawrence Vail Coleman, director of the American Association of Museums, Johnston took her collection of Carnegie survey photographs to New Orleans, where in 1938 she organized an exhibit at the historic Cabildo next to St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter.(39) Her work helped raise public awareness and support for historic preservation in the city.

The Big Easy captivated her and she lent her name and prestige to historic preservation efforts there long before moving to the city in 1944. While visiting in 1937, she told Harnett T. Kane of the New Orleans Item—

In the old French Quarter, there flourishes something that has no American counterpart. There is a certain kinship among Charleston, St. Augustine and your city. But New Orleans surpasses them in rare beauty of iron work, of outdoor and indoors arts and crafts in a romance of aspect and spirit, of character and charm that are unique in America.(40) |

Her comparison of those cities comes as no surprise since she worked extensively in all three, bolstering the efforts of local preservationists with her photographs and testimonials in support of historic buildings and streetscapes. In 1931, two years after Johnston had photographed the city, Charleston passed the first city zoning ordinance in the United States to protect historic buildings. New Orleans followed suit in 1937, establishing the nation's second historic district and the Vieux Carré Commission to preserve the historic character of the French Quarter.(41)(Figure 12)

Preservation efforts in St. Augustine, Florida, picked up in 1936—the same year Johnston had accepted an invitation from the St. Augustine Historical Society to document historic buildings and then mount a photographic exhibit at the city's Ponce de Leon Hotel.(42) John C. Mirriam, the president of the Carnegie Corporation of Washington who had helped Johnston obtain funding for this project, stressed to the St. Augustine Chamber of Commerce that Johnston's photographs were good publicity for the city. "I have felt," he wrote to the chamber, "that Miss Johnston's photographs and the work which she is doing showing things of interest and beauty in St. Augustine, are of great importance. We need exact records, detailed pictorial presentations, and also the evidence of what is beautiful and interesting" in the city.(43) As in Charleston and New Orleans, Johnston's photographic inventory of historic buildings in St. Augustine attracted considerable public attention, financial assistance, and ultimately legislative support for historic preservation.(44) Society director Verne Chatelain, a former National Park Service historian and assistant director who had supported Johnston in Virginia and helped secure Carnegie funding for the St. Augustine survey, kept Johnston informed of local preservation developments, writing her months later that—

As to my own plans, I hope to be here until the final drafting of the Zoning Ordinances, which we have been working on for the past two to three months. The state [legislature] passed five restoration bills, all that we asked for, and fifty thousand dollars, so that whole-hearted state cooperation is now fully assured.(45) |

He attributed much of this activity and success to Johnston's photographs and exhibit.

Johnston continued her Carnegie-funding survey of the South with a photographic survey of Louisiana plantation houses along the Mississippi delta, arranged with the help of Louisiana architect and HABS district officer Richard Koch.(46)(Figure 13) She received another Carnegie grant in December 1938 to photograph historic buildings in Georgia and Alabama, marking the end of the fieldwork in typical fashion with an exhibit of 70 photographs of Savannah at that city's Telfair Gallery. She also delivered 150 prints to the Association for the Preservation of Savannah Landmarks. The Georgia survey resulted in a book co-authored by Frederick D. Nichols, a young architect and architectural historian at the University of Virginia who had worked for HABS until 1940. Published in 1957, several years after Johnston's death, The Early Architecture of Georgia remains one of the standard works on Georgia architecture and a model for statewide studies.(47)

Technique, Equipment, Philosophy

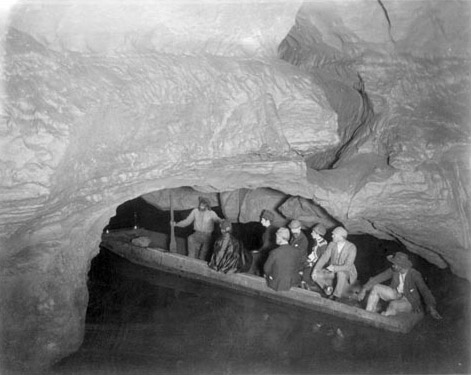

Later in life, Johnston downplayed the intricacies of her photographic technique by casting herself as someone who did not care for technical matters. At the age of 85, she boasted there was "nothing retiring in my disposition. I wore out one camera after another, and I never had any of those fancy gadgets. Always judged exposure by guess."(48) She said about her subterranean photographic expedition at Mammoth Cave in Kentucky in 1892: "As to the difficulties, disasters, but ultimate triumph of the photographic campaign, when I sought to vanquish the archenemy darkness with flash powder, it is too long a story;" yet, she was an innovator for her early use of magnesium powders in lighting the cave interiors.(49)(Figure 14)

Although she made her photographic technique sound effortless, its intricacies were, in fact, numerous. She was very meticulous about lighting and viewpoint in her architectural and other photographs. She made sure that conditions were exactly the way she thought they should be—

I won't make a picture unless the moon is right, to say nothing of the sunlight and shadow! Most of the time I have to be excruciatingly patient waiting for the light to get precisely right. Sometimes I have a tree cut down, a stump removed, or a platform erected to get the proper perspective. I have shot pictures from on top of boxcars, and loaded trucks. If I'm in a city street, I often call the police to hold up or detour traffic while I photograph a place. When I photograph an interior, I usually shoo the family out, lock the door and buckle down to business.(50) |

In the field, she took great pride in arranging the scene and adjusting her camera settings to get exactly the image she wanted. In this respect, she differed radically from modernist photographers, who preferred to manipulate their images afterwards in their laboratories and then publicize their techniques as original. Johnston maintained that she was an exponent of "straight," that is to say, un-manipulated, photography, leaving what she called trick angles to her contemporary, the photographer Margaret Bourke-White, and surrealism to the artist Salvador Dalí.(51) Occasionally, though, she manipulated the point of view so that she could employ a particular photographic angle. She also made decisions spontaneously, a practice that Sadakichi Hartmann referred to in 1904 as "composition by the eye."(52)

Johnston used an 8 by 10 inch view camera with the shutter speed "slowed way down" to reduce the aperture, allowing for greater depth of field and detail.(53) The typical, fully equipped view camera of her day had a rising, sliding, and tilting front standard and a swinging and tilting back standard for framing the view and correcting for perspective distortion. To set the camera level, she raised the front and then tilted the camera upward until satisfied with the location of the object on the ground glass. She then adjusted the rear standard to eliminate the distortion. Next, she focused the camera and stopped down the aperture until the definition was "good all over the plate."(54)

Johnston took as many photographs of a single subject as possible so that she might have a good set from which she could choose the most evocative images. While on site, she jotted down physical descriptions, historical notes, and personal observations and thoughts. She tempered the scientific precision of her recording method with personal insights and emotions that she expressed in unaffected and accessible prose. As for the subject matter, she firmly believed that houses and historic architecture were reflections of people and their culture. Quoting from the book Houses in America by Ethel Fay and Thomas P. Robinson, she told a crowd at a North Carolina art gallery in March 1937 that "When you build a house, you make a record of yourself, and experts in houses can tell by the house you building and live in what kind of person you are."(55)

By the end of her career, Johnston preferred the overlooked 17th- and 18th-century buildings of an everyday sort, which she called "primitives," to the colonial mansions, country estates, and other major monuments that had absorbed much of her attention in her earlier years.(56)(Figure 15) She was interested in the changes made to these buildings over time by successive generations of inhabitants. In her photographs, she emphasized the bucolic and picturesque aspects of the South to show the region as a civilized, if not necessarily urban, place. She knew that neglected buildings often became lost, and she considered her photographs the next best thing to restoring or preserving the buildings themselves. She often intimated that the decay of buildings due to indifference and neglect was comparable to destruction caused by the ravages of war, and she used photography to promote their preservation.(57) On at least one occasion she described herself as "hurrying on the road ahead of the march of neglect and progress."(58)

Johnston attempted to serve society through her art. Her photo-documentation of the Hampton Institute, an historically black institution, and the Washington, DC, public schools, completed at the turn of the 20th century, helped shed much-needed light on contemporary institutions working for the betterment of American society.(Figures 16-17) Her Carnegie survey of the architecture of American South influenced how Americans saw and treated themselves and their physical surroundings.

|

Figure 16. Johnston took this photograph of a Washington, DC, public elementary school cooking class around 1899. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

|

Figure 17. This photograph of Johnston's showing a cooking class for African American women at Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, dates from around 1899. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

Johnston's later work for the Carnegie Corporation was the culmination of her life-long interest in American buildings and landscapes. Taken together, her various projects—from her earliest sketches of buildings in Washington, DC, to her many exhibits and publications—measure the depth of her commitment to raising public awareness and appreciation of historic architecture and its preservation. One of the first American photographers to specialize in architectural documentation, Johnston also helped set the technical standards for the profession in the United States.(59)

Johnston's Material Legacy

Johnston's material legacy is measured in her many newspaper and magazine articles and books, and in the collections of photographic negatives, prints, stereopairs, and papers left to the Library of Congress and other archives. The Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers at the Library include her diaries, correspondence, speeches, manuscripts, notes, maps, financial papers, and newspaper and magazine articles. Johnston gave copies of all the photographs she made during her lifetime (from about 1888 to 1947) to the Library's Prints and Photographs Division. This collection of images, known as the Frances Benjamin Johnston Collection, also includes photographs she collected. Among the photographic materials are approximately 20,000 silver gelatin and cyanotype photographs, 37,000 glass and film negatives, 1,000 lantern slides, 17 tintypes, some autochromes, along with photo albums, scrapbooks, architectural and other drawings, business cards, newspaper clippings, Johnston's camera, and her typewriter.(60)

The Carnegie Survey of Architecture of the South Collection, also housed in the Prints and Photographs Division, consists of nearly 8,000 photographs (negatives and prints) of historic buildings and sites in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia that Johnston had produced under successive Carnegie Corporation grants between 1927 and 1943.(61) Her photographs of Fredericksburg and Falmouth, Virginia, formed the foundation of the Library's Pictorial Archives of Early American Architecture (PAEAA).(62) Begun in 1930, PAEAA solicited negatives and prints of historic buildings from donors across the country. The PAEAA materials, in turn, formed the foundation of the Historic American Buildings Survey collection at the Library.(63)

The Baltimore (Maryland) Museum of Art, the Enoch Pratt Free Library (Baltimore, Maryland), the University of Virginia (Charlottesville), the Virginia Museum of Art (Richmond), Duke University (Durham, North Carolina), the Art Institute of Chicago (Illinois), the Carnegie Institute (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill), the Museum of Modern Art (New York City), the California Museum of Photography (Riverside), the Louisiana State Museum (New Orleans), and the Huntington Library (San Marino, California) also preserve collections of Johnston's photographs.

In 1966, the Museum of Modern Art published The Hampton Album, a collection of 44 photographs Johnston had taken in 1899 and 1900 of the Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, a training school for black and American Indian youth.(64) One of several such early photojournalism projects of hers that addressed issues of social justice and equality, the Hampton photos attracted critical attention and inspired a rigorous study of her life and work that continues to this day.

Johnston died in New Orleans on May 16, 1952, at the age of 88. TIME Magazine described her as a "onetime news photographer who had an inside track to the White House because of her friendship with Presidents Harrison, McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt."(65) Her Washington, DC, social connections may have impressed her contemporaries during her lifetime, but her material legacy—writings and thousands of images—endures as a lasting record of American society at an important time in its history.

About the Author

Maria Ausherman is working on a book about Frances Benjamin Johnston. She lives in New York City.

Notes

1. This essay is based on a forthcoming book, tentatively titled "A Record in Black and White: The Legacy of Frances Benjamin Johnston, American Photographer." For more information on Frances Benjamin Johnston's life and work, see also Bettina Berch, The Woman Behind the Lens: The Life and Work of Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1864-1952 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000); and Pete Daniel and Raymond Smock, A Talent for Detail: The Photographs of Miss Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1889-1910 (New York, NY: Harmony Books, 1974).

2. Frances Benjamin Johnston, "What a Woman Can Do with a Camera," Ladies' Home Journal (September 1897): 6-7.

3. First defined by Peter Henry Emerson in 1886 and then developed by photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz, the term "pictorial photography" refers to photography that goes beyond contrived studio scenes and endeavors to achieve pictorial representation through painterly effects of line, light, and composition. A pictorial photograph, rather than being either a work of art or science, was considered a union of the two.

4. Johnston traced her own family history, records of which survive in the Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (MDLC).

5. Lincoln Kirstein, "A Note on the Photographer," The Hampton Album (New York, NY: The Museum of Modern Art, 1966), 53. For more information on female American artists in France, see Elizabeth Brown, "American Paintings and Sculpture in the Fine Arts Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893," Ph.D. Diss., University of Kansas, 1976), 284-5; Catherine Fehrer, "New Light on the Académie Julian and Its Founder," Gazette des Beaux-Arts 103 (1984): 207-16; Katherine de Forest, "Art Student Life in Paris," Harpers' Bazaar 33 (July, 7 1900): 628-32; Mary Alice Heekin Burke, Elizabeth Nourse, 1859-1938: A Salon Career (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art, 1983); Geraldine Rowland, "The Study of Art in Paris," Harpers' Bazaar 36 (September 1902): 756-61; Charlotte Yeldham, Women Artists in Nineteenth Century France and England, 2 vols. (New York, NY: Garland, 1984); Theodore E. Stebbins, Carol Tryen, and Trevor Fairbrother, A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting, 1760-1910 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1983) 160-61; and Helene Barbara Weinberg, The American Pupils of Jean-Leon Gerome (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1984), 91, 93 and no. 6.

6. The Washington Art Students' League also went simply by the name of the Art Students' League. See Clarence Bloomfield Moore, "Women Experts in Photography," Cosmopolitan 14 (March 1893); "Art Students at Work," The Washington Post, October 16, 1888; "Frances Benjamin Johnston," Macmillan Biographical Encyclopedia of Photographic Artists and Innovators (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1983), 310-311; Frances Benjamin Johnston, diary entry, January 10, 1911, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC; Catalogue of the Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art (Belmont, MA: A.W. Elson & Company, 1913), 7-11; Constance McLaughlin Green, Washington Village and Capital, 1800-1878 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1962), 339-362.

7. "Art Students at Work;" Susan Hunter, "The Art of Photography: A Visit to the Studio of Miss Frances Benjamin Johnston" (c. 1895), Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

8. Hunter, "The Art of Photography."

9. Around 1887, Elizabeth Sylvester, a friend from the League, asked Johnston to stand in for her temporarily as a Washington correspondent for a New York paper. It was a short-term commitment, but it led to offers with other newspapers and periodicals.

10. William Welling, Photography in America: The Formative Years, 1839-1900 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1987), 303.

11. Thomas W. Smillie, "Smithsonian Institution: History of the Department of Photography," July 24, 1906, RU55, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, DC; "History of the Section of Photography of the Smithsonian Institution: Its Establishment and Early Activities," 1965, RU55, Smithsonian Institution Archives; Thomas W. Smillie to Frederick W. True, December 29, 1899, RU55, Smithsonian Institution Archives; Hunter, "The Art of Photography;" Moore, "Women Experts in Photography;" Thomas Smillie to G. Brown Goode, July 26, 1890, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

12. Frances Benjamin Johnston, "Uncle Sam's Money," Demorest's Family Magazine (December 1889-January 1890), n.p.

13. Frances Benjamin Johnston's illustrated essays for Demorest's included "The White House" (May 1890); "Some Homes Under the Administration: Levi P. Morton, Vice President" (July 1890); "Some Homes…: John Wanamaker, Postmaster General" (August 1890); "Some Homes…: Senator Hearst of California" (October 1890); "Some Homes…: Senator Sawyer of Wisconsin" (December 1890); "Through Coal Country" (March 1892); "Mammoth Cave by Flashlight" (March 1893); and "A Day at Niagara" (August 1893).

14. "The Evolution of a Great Exposition," Demorest's Family Magazine (April 1892). Under the direct supervision of Charles Dudley Arnold, the exposition's chief photographer, Johnston traveled back and forth between Washington and Chicago to record the site of the future exposition, the construction of the exposition buildings, and, finally, the activities of the fair itself. In 1901, she and Smillie photographed the U.S. National Museum exhibits at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. Johnston served on the international jury of awards at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri.

15. For more on Bain, see Emma H. Little, "The Father of News Photography, George Grantham Bain," Picturescope 20 (autumn 1972): 125-132.

16. Johnston photographed Presidents Grover Cleveland (1885-1889; 1893-1897), Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893), William McKinley (1897-1901), Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909), and William Howard Taft (1909-1913).

17. She received commissions from Bertram G. Goodhue, John Russell Pope, Charles A. Platt, Grant LaFarge, Charles McKim, and others responsible for recently constructed houses on private estates. The New York-based architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White used Johnston's photographs of the White House and the Octagon House for restoration purposes.

18. Miss Impertinence, "They Photograph the Smart Set," Vanity Fair (n.d.), 18-19, quoted in Amy S. Doherty, "Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1864-1952," History of Photography 4 no. 2 (April 1980): 108.

19. Ben Yusef, Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr., the leader of the Pictorial Movement in photography, and the successors to the firm of Napoleon Sarony.

20. Edward L. Wilson, Wilson's Photographic Magazine 37 (April 1900): 152. Johnston and Hewitt ended their partnership in 1917. Hewitt continued photographing gardens and estates for magazines and other publications through the 1930s.

21. Frances Benjamin Johnston to Mr. Barron, October 14, 1923, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

22. Library of Congress, "Press Release," no. 448 (n.d.).

23. Johnston retained an interest in travel and other journalistic writing even though private garden and estate commissions dominated her work. By 1924, she had developed the idea of publishing a garden guide to Europe and by January 1927 claimed to have had the first two chapters "well on the stocks." Although this publication was never realized due to the expense, she managed to incorporate much of her research into her lectures and photo captions. Captions she provided for photos published in Town and Country magazine during the late 1920s, for instance, were usually three pages long, single-spaced, and included historical and descriptive information of the site. For the guide to Europe, see Johnston to Helen Fogg, January 12, 1927, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

24. Frances Benjamin Johnston, interview with Mary Mason, WRC National Broadcasting Company, February 12, 1936, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

25. Built for William Fitzhugh between 1768 and 1771, the Georgian plantation house, Chatham Manor, is now part of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Helen Devore and her husband, Daniel, bought Chatham Manor in the 1920s and restored the building and grounds. They sold the property in 1931 to industrialist John Lee Pratt who, in turn, donated it to the National Park Service. "Chatham Manor," http://www.nps.gov/frsp/chatham.htm, accessed May 15, 2007.

26. A member of the Women's National Press Club, Johnston made certain that her work received coverage in the national media. She mailed sets of photographs to the Washington Star, Baltimore Sun, Philadelphia Ledger, the Boston Transcript, and the Richmond Times-Dispatch for publication as features in the Sunday editions. The Fredericksburg exhibit eventually made its way to the Library of Congress in Washington, where it attracted the attention of Herbert Putnam, the Librarian of Congress, Leicester B. Holland, the Chair of Fine Arts at the Library, and several Members of Congress.

27. Henry Irving Brock, Colonial Churches in Virginia (Richmond, VA: The Dale Press, 1930).

28. Frances Benjamin Johnston to Leicester B. Holland, May 20, 1930; and Johnston to Edmund S. Campbell, June 5, 1932, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC. Information about the Carnegie Corporation of New York is available online at http://www.carnegie.org/.

29. Others who wrote to the Carnegie Corporation on Johnston's behalf included the architectural firm of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, the Virginia Library Association, the library at the College of William and Mary, and state historical institutions in Richmond, Virginia. All emphasized the significance of Johnston's work for places that had never been surveyed. See Frances Benjamin Johnston to Leicester B. Holland, May 20, 1930; Johnston to Edmund S. Campbell, June 5, 1932; Campbell to Frederick P. Keppel, October 14, 1932; Campbell to Johnston, October 26, 1932; and Keppel to Johnston, January 26, 1933; Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

30. Robert M. Lester, Secretary of the Carnegie Corporation, to Frances Benjamin Johnston, November 6, 1934; Johnston to Lester, December 16, 1934, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

31. Zelda Branch, "Preserving a Nation's Architecture," Christian Science Monitor (November 11, 1936): 12-13; Frances Benjamin Johnston to John Lloyd, President of the University of Virginia, December 2, 1933, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

32. See Charles Magruder, "The White Pine Monograph Series," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 22, no. 1 (March 1963): 39-41. Frank Edwin Wallis, Old Colonial Architecture and Furniture (Boston: G.H. Polley & Company, 1887); American Architecture, Decoration and Furniture of the Eighteenth Century (New York, NY: P. Wenzel, 1896); An Architectural Monograph on Houses of the Southern Colonies (Saint Paul, MN: White Pine Bureau, 1916); also Fiske Kimball to Leicester B. Holland, November 22, 1932; Holland to Kimball, November 23, 1932; Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

33. Alice Ravenel Huger Smith and Daniel Elliot Huger Smith, The Dwelling Houses of Charleston, South Carolina (New York, NY: Diadem Books, 1917); Fiske Kimball, Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the American Republic (1922; New York: Dover Publications, 1966).

34. Frances Benjamin Johnston to Leicester B. Holland, June 20, 1935, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

35. Frances Benjamin Johnston to Mr. and Mrs. Cannon, February 6, 1939, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

36. Mrs. Charles Cannon facilitated the Colonial Dames contact.

37. Francis Benjamin Johnston and Thomas T. Waterman, The Early Architecture of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1941).

38. Frances Benjamin Johnston to the Daughters of the American Revolution Regents of Lexington, KY, August 1, 1942, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

39. Johnston had told Lawrence Vail Coleman that the Cabildo provided the "proper setting" for her show. Johnston to Coleman, April 21, 1937, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

40. Harnett T. Kane, New Orleans Item, November 19, 1937, and August 4, 1939, quoted in Charles B. Hosmer Jr., Preservation Comes of Age: From Williamsburg to the National Trust, 1926-1949, vol. 1 (Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1981), 303.

41. For more information on the commission, see "Vieux Carre Commission," http://www.cityofno.com/Portals/Portal59/portal.aspx, accessed May 15, 2007.

42. This St. Augustine Historical Society exhibited 125 of Johnston's photographs of about 40 historic buildings at the Ponce de Leon Hotel in January 1937.

43. John C. Merriam to M.H. Westberry, President of the St. Augustine Chamber of Commerce, January 19, 1937, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

44. Along with her contemporary, the historian Talbot Hamlin, Johnston strongly urged architectural survey as the first step in the historic preservation process. In 1940, Hamlin pressed for a comprehensive inventory of New Orleans architecture. Despite the efforts of Johnston, Hamlin, and many others, a systematic building by building inventory was not completed until the early 1970s. Hosmer, 1:260.

45. Verne Chatelain to Frances Benjamin Johnston, September 24, 1937, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC. When he was with the National Park Service, Chatelain had supported Johnston's work in Virginia. The St. Augustine Historical Restoration and Preservation Commission (now the Historic St. Augustine Preservation Board) was established in 1959.

46. That project resulted in an exhibit at the New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club in 1940. Fortier to Frances Benjamin Johnston, October 12, 1937; Richard Koch to Johnston, December 28, 1940, Kane quoted in Hosmer, 1: 303.

47. Frederick D. Nichols, The Early Architecture of Georgia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1957).

48. "Speaking of Pictures," Life Magazine (April 25, 1949): 14-16.

49. Johnston, "Mammoth Cave by Flash-Light;" William Welling, Photography in America: The Formative Years 1839-1900 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987), 309-313. Johnston's photo journalism piece on Mammoth Cave, published in Demorest's, highlighted the journey to the cave, the natural beauty of the cave interior, and the gargantuan scale of the place. It is considered to be the first successful, thorough photographic record of the cave's large interior spaces. As Johnston explained in her essay, the cave system is spread across hundreds of acres and consists of more than 220 avenues having an aggregate length of 200 miles, 47 domes, 23 deep pits, 8 waterfalls, and several bodies of water including 3 rivers, 2 lakes, and a sea. Johnston's Mammoth Cave essay was an instant success and led to an exhibit at the University of Nebraska and the publication of 25 of the photographs as a book in 1893.

50. Harnett T. Kane, "New Orleans Architecture Is Being Saved In Pictures," The Sunday Item-Tribune (New Orleans), May 22, 1938.

51. Ibid.

52. Sadakichi Hartmann, "A Plea for Straight Photography," American Amateur Photography 16 (1904): 101-9; also Hartmann, "On the Possibility of New Laws of Composition," Camera Work 30 (1910): 39; Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography (New York, NY: The Museum of Modern Art, 1982), 167-197.

53. Frances Benjamin Johnston, "What a Woman Can Do With a Camera," Ladies' Home Journal 14, no. 10 (September 1897): 6.

54. W. X. Kincheloe, "On Photographing Homes," Photo Era 50, no. 4 (April 1923): 177-184.

55. Ethel Fay and Thomas P. Robinson, Houses in America, as quoted by Johnston in a lecture dated March 21, 1937, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

56. See Zelda Branch, "Preserving a Nation's Architecture," Christian Science Monitor, November 11, 1936. Johnston's own life and her correspondence with homeowners of historic residences show that she understood the importance of adapting buildings for modern use. Paul Kester and Kate Doggett, homeowners in Fredericksburg, Virginia, wrote to Johnston that deaths in their families made them consider giving up the buildings associated with the deceased. Yet, Johnston encouraged them to persevere lest other owners let the buildings fall into ruin. See Frances Benjamin Johnston, interview with Mary Mason, WRC National Broadcasting Company, February 12, 1937, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC; Paul Kester to Frances Benjamin Johnston, June 25, 1927, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC; Kate Doggett to Frances Benjamin Johnston, January 20, 1928, Frances Benjamin Johnston Papers, MDLC.

57. Kane, "New Orleans Architecture is Being Saved in Pictures."

58. Ibid.

59. See Helen Powell and David Leatherbarrow, eds., Masterpieces of Architectural Drawing (New York, NY: Abbeville Press, 1982), 68.

60. Information about the Frances Benjamin Johnston Collection at the Library of Congress is available online at http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/131.html, accessed May 12, 2007. The Library has also digitized more than 1,600 images from the Frances Benjamin Johnston collection. These images are available online from the Library's Prints & Photographs Division website, http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/, accessed June 6, 2007.

61. Information about the Carnegie Survey of the South Collection at the Library is available online at http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/039.html, accessed May 12, 2007.

62. Information about the PAEAA is available online at http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/186.html, accessed May 12, 2007.

63. Information about the HABS Collection at the Library of Congress is available online at http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/145_habs.html, accessed May 12, 2007.

64. Lincoln Kirstein, The Hampton Album (New York, NY: The Museum of Modern Art, 1966).

65. TIME Magazine (June 2, 1952), http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,857255,00.html, accessed May 30, 2007.