Viewpoint

Por la encendida calle antillana: Africanisms and Puerto Rican Architecture(1)

by Arleen Pabón

Por la encendida calle antillana Walking down the Antillean street |

When Puerto Rican poet Luis Palés Matos wrote these well-known lines of his poem "Majestad Negra" (Black Majesty), he was trying to capture Tembandumba's impact as she walked down an Antillean street.(3) Thanks to his imagery, we can picture the effect of her provocative progress on the population. The alluring street has no name. The poem is about all streets, a metaphor for all Caribbean walks of life illuminated by African presence.

"Majestad Negra," like this paper, deals with intangibles. One of the key components of Puerto Rican culture is its African heritage, particularly in architecture. But, just as Tembandumba lives only in a poem, evidence of African impact on the island's architecture is barely tangible, dimly surfacing only when we interpret some rapidly disappearing ruins or a few old photographs.

This paper is about things that are no more. It deals with absence and tries to dislodge two cherished Western beliefs. First, (to use Nikolaus Pevsner's grand metaphor) only cathedrals and not bicycle sheds deserve academic scrutiny. Second, cultural significance by historic preservation standards is only embodied in physically identifiable artifacts.

Many years ago, when I first tried to understand why historic preservation (or architectural history for that matter) seldom dealt with aspects of herstory (as opposed to history), I realized that many academics and preservation practitioners had a narrow vision. Take for example the historical development of Caribbean domestic architecture. Seldom is the topic academically explored; seldom, if ever, is it analyzed as a significant component of the region's cultural heritage. While a few Caribbean dwellings, most always examples of the big house, are presented as transplanted examples of grand European architecture, native and African influences are treated in a perfunctory manner, if at all. Simply put, the issue of architectural diversity has not been analyzed in a holistic fashion.

As a result, society fails to understand how the slave hut was able to breed as many, if not more, important domestic ideas as the big house. More significantly, we fail to consider the role that subordinate groups, such as women and, in this case, Puerto Ricans of African descent, played in the creation of the island's architectural heritage. African influence on Puerto Rican architecture is a nonsubject in part because the following questions have not been addressed: Can an enslaved group contribute to a culture's architectural development? If this is possible, are huts and similarly unassuming structures culturally significant? How are physically absent architectural artifacts to be analyzed? Most importantly, is such analysis relevant in historic preservation?

For decades, only silence answered these questions. Unfortunately, a void in knowledge is construed as nonparticipation. The time has come to follow Tembandumba's lead and walk down the Antillean "street" of architectural knowledge, shedding light upon Africanisms present in Puerto Rican architecture.(4)

The Native Hut

By all accounts, Caribbean architecture mesmerized Spaniards when they first encountered it. They were surprised by the apparent fragility of the vernacular house, both in terms of form and materials. The climate and nomadic character of the natives dictated informal arrangements of spaces, as well as the use of natural materials.(5) It quickly became obvious that Columbus's enthusiastic description of Puerto Rican houses as "very good" (muy buenas) and able to "hold their place in Valencia" was not accurate.(6) The native hut, known throughout the Caribbean as the bohío, was a fairly simple arrangement of reeds, grass, bark, and foliage.(7)

Caribbean natives did not construct following Valencian or European architectural ideals; Columbus's lavish interpretation was atypical in the bevy of descriptions generated with time. There were no European-style aesthetic arrangements in the Caribbean native house. Ironically, the native's most common building was very similar to the Vitruvian hut: a makeshift affair, open to nature.(8)

When Europeans first came into contact with the North American continent, pristine spaces exhibited the lightness of the natives' touch. The absence of architectural bravado (a characteristic of European experience) and traditional associational ties created the illusion that the continent was architecturally mute. European architecture speaks diverse languages that, in turn, allow for multiple interpretations. Since unpretentious structures like the bohío are prima fasciae devoid of the traditional character that reflects complex architectural language, many leading historians (then and now) believe that such structures lack relevance and significance. While it might not qualify for inclusion in Europe's architectural pantheon, the bohío became the basis for the island's most common architectural artifact, the Puerto Rican house.

There exists a well known, deep and complex interaction between building and culture. This is the case with all cultures, even "prehistoric" ones. More than a third of the world's population lives in structures made of mud, and a sizable number still lives in tents.(9) Are we to ignore these expressions or judge them by European standards?

In order to correctly evaluate the architectural significance of nontraditional architectural artifacts, we must abandon traditional Western models of interpretation. We need not follow Columbus's route of exaggeration. Rather, we should analyze how architecture expresses social and experiential diversity. It would be a mistake to consider Puerto Rico's humble abodes, whether erected by the indigenous Taíno or immigrant Africans, to be mere instinctual solutions to the problem of survival. It is paradoxical that even the humblest of these artifacts, in trying to defy dangers implicit in living, is totemic of meaningful existence.

Certainly, some viewed the lack of architectural trappings as cultural inferiority, but not all. During the 18th century, Puerto Ricans(10) were described as "An abstraction of all ideas of progress and social obligations…Ibaros [sic] without truly understanding their negation of material things are the world's greatest philosophers, recognizing no need for artificial things."(11) Their abodes were then a reflection of a peculiar cultural response to both life and the pursuit of an existence. Labels such as "prehistoric" are secondary in this type of interpretative analysis. The drama of living is common to all humans, whether born millennia ago or centuries from now. The primary stage for this drama, whether located in the Caribbean or the Antipodes, is the artifact we call a house.

The African Experience

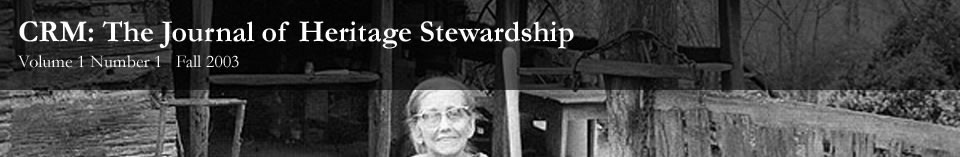

When slavery began in Puerto Rico in the 17th century, many slaves lived in barracones, where they experienced a total and degrading lack of privacy.(12) (Figure 1) Later, in the 19th century when sugar cane production was established in Puerto Rico, some slaves were allowed to have their own huts. In spite of its humble ethos, this hut, a condensation of native and African ideas, is iconic of a momentous cultural transformation. The hut provided something the barracones did not: a place where personal roots could be planted.

It is documented that Caribbean islanders followed—and still do—specific rites as they built their houses.(13) From Guadeloupe's ceremony marking the cutting down of the master post of the hut; (14) to the Puerto Rican phrase, plantar jolcones, which literally translates into "planting" the wooden structural posts; to Cuban religious ceremonies that took place at the construction site, this rite of passage was important. There was dignity associated with possession of a hut, even the simplest one, for it represented many hopes and dreams. It is paradoxical that so much feeling could go into such an architecturally basic form.

The native bohío had much in common with many African house types, enshrined in the memories of those who experienced the African diaspora. However, significant variations on the local prototype can be detected. Africanisms found their way into the native architectural experience partly because slaves were in charge of constructing their abodes.(15) As a result, past experiences and modes of construction were replicated in the new environment. After all, not only were there similarities in terms of climate, as Diego de Torres Vargas pointed out as early as 1647, but also in construction materials.(16) This approach should not cause surprise, for Europeans, just like Africans, followed the exact same pattern: architectural styling and construction techniques closely mimicked those found in their native land, in spite of climatic differences.

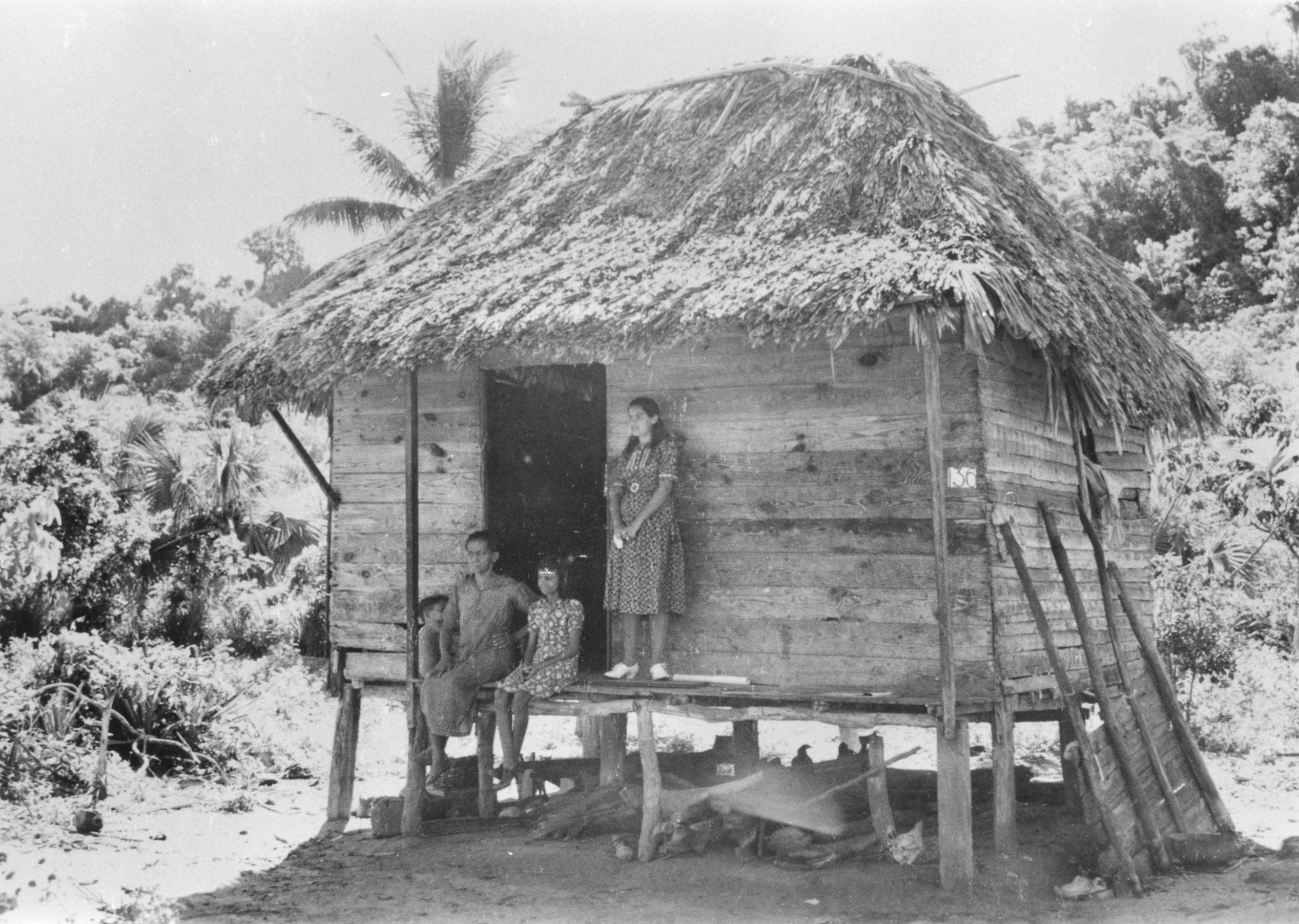

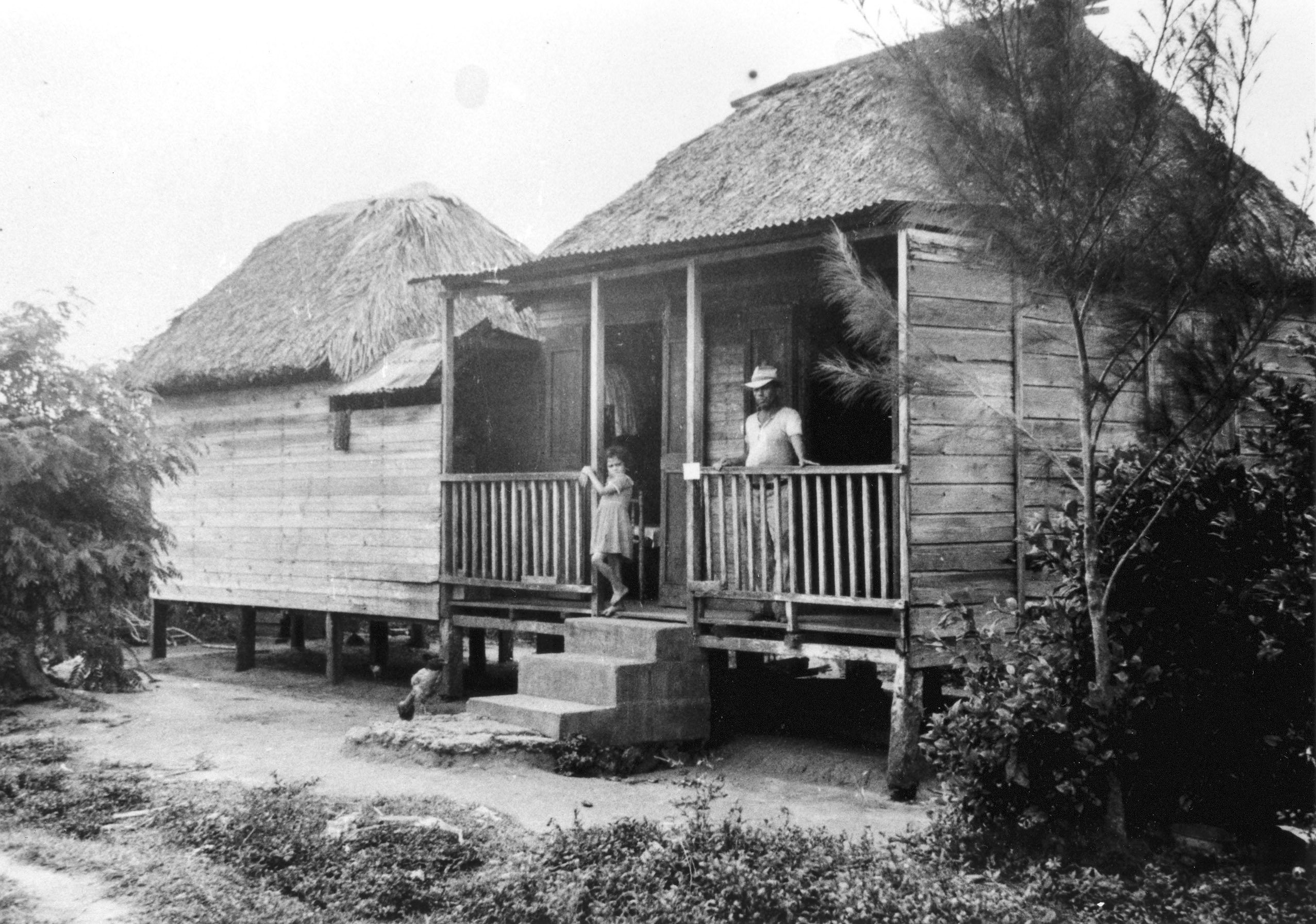

Most archeological findings corroborate historical descriptions of the Amerindian huts: a round or oval floor plan covered with a thatched roof and open-work wooden walls.(17) Consensus is not, however, as widespread regarding the idea that Europeans introduced the square or oblong hut to the island.(18) (Figures 2 and 3) We do know that the vernacular hut morphology experienced a transformation and that oblong (at times square) floor plans came to be preferred. Since the change was not the result of different construction materials or climatic conditions, the new preference is probably related to diverse experiences: from new construction techniques to religious and cultural ideas imported not from Europe but from Africa. The ideas did not reflect European construction techniques or native architectural expressions. Comparisons can be made with African building traditions, but more research and interpretative activities are needed in order to correlate the bohío's development with architectural traditions present in African countries such as modern-day Nigeria, Congo, and Senegal.(19)

|

Figure 3. Changes in the original Puerto Rican bohío type are evident here. A second unit next to the original one was a common solution to the needs of a growing family. (Unknown source, 1916.) |

African experience also transformed the minimalist approach that characterized the native bohío. Most historical descriptions make a point of emphasizing its "open character," evidenced in most contemporary images. These houses, termed bohíos from the very early stages of the Spanish conquest, were described some decades later in the following manner: "Four tree trunks placed into the soil with smaller ones placed across, covered by dried yaguas, [raised] two to three feet from the ground to keep the humidity out and having a small staircase to enter the house." The description further mentions that no nails or other European fasteners were used and that the hut was completely open with only the sleeping area barely protected from the "excessive night air" (fresco excesivo). It was here the inhabitants slept, grouped together "like savages." There was no furniture, no table, no bed or crib, only hamacas made with "Mayagüez bark" (at a cost of two reales). The ménage was composed of instruments "provided by Nature," such as palm leaves, which were folded and sewn to make dining plates, wash basins, baskets used as commodes, and even funeral caskets for children.(20)

While in the United States, the slave cabin "recapitulated frontier architecture," in Puerto Rico, African descendants altered the native typology and made possible a new organization, both spatial and contextual.(21) As mentioned before, instead of the round floor plan common to the natives, the square or rectangle was preferred. In addition, the makeshift, nomadic, native ethos was also transformed: as time went on, the bohío acquired more substance both in terms of materials and structural components. The most interesting transformation was a switch to a more introverted character. The transformed hut, in most cases, had no windows and only a small door to the interior.(Figure 4)

This lack of establishing direct connections with the exterior was a deviation from the native arrangement. Opening interiors to the outdoors is common in a tropical milieu, characterized by its hot, humid weather. Enclosure is probably a most relevant Africanism. Walls define boundaries: within them you have status, personal definition. If you were a slave, outside of the seemingly flimsy boundaries established by the walls of your bohío you had nothing and were considered nothing. The more openings present in a hut, the more transparency and lack of privacy experienced within the interior. For the enslaved population (and you were enslaved whether you were a slave, a freed slave, or an arrimao) the bright outdoor space was not their space but a cruel stage, a vivid reminder of the unfortunate situation that they experienced.(22) A dark, enclosed interior created a sense of intimacy that protected, to paraphrase Gaston Bachelard, the user's immense intimacy from prying eyes and the real world.(23) Completely enclosed spaces provide respite from the heat as well.

It is recorded that all over the Caribbean, in the few cases where windows do appear, blind shutters closed them, per African tradition, in marked contrast to fancy, more transparent European shutters.(24) When inside the bohío, you wanted to shut out the exterior, not to bring it in. This characteristic became an intrinsic part of the traditional Puerto Rican house. To this day, most windows, when shut, allow no light to come in.

As a result of this desire for privacy, the entry point—the place where the conversion between public and private, profane and sacred, took place—was limited to one very small opening. Given that the entrance was considered a "weak" point in the desire for privacy and interior autonomy from the exterior, the access, when the floor was higher than the ground, was a small, roughly conceived wooden ramp or staircase.(Figure 5) It was common for the interior space to serve as a living-cum-sleeping place (such generic spaces were called piezas or aposentos by my grandmother) that either had a dirt floor or a wooden platform on stilts (zocos). Most lived al fresco most of the day, working on their labors. The desire to "forget" the reality of their lives could only be exercised at night, when their time was their own. At night they preferred a completely enclosed area in order to reinforce a sense of isolation from the "cruel stage."

The floor had a unique symbolism and, in keeping with its significance, had its own special name, soberao, a word of unknown origin.(25) The soberao is not just a floor but evidence of a dwelling locus. For a woman her soberao proved not only that she had a house but also that she was the lady of that house.(26)

In the United States, slaves at times insisted on a particular type of floor finish as an act of appropriation. Susan Snow, a former slave raised on a plantation in Jasper County, Mississippi, reported that most of the slave cabins had wooden floors, except the one that was assigned to her African-born mother: "My ma never would have no board floor like the rest of 'em, on 'count she was a African—only dirt." By rejecting an apparent material "improvement," this woman recreated in her house an aspect of African domestic life with which she was more comfortable.(27)

The feel and texture of the dirt against bare feet, the smell of packed earth, and the darkness enveloping these sensations were probably a reminder of the long-gone African past. In Puerto Rico, the dirt floor slowly evolved into the raised floor surface, a solution aimed at providing protection against tropical rain and the ever-constant humidity. However, there is evidence that dirt floors were used well into the 20th century.(Figure 6)

A bohío was more than just a shelter; it was a womb-like setting that provided comfort by means of privacy. The bohío experimented with minimalist architectural ideas and its unique personality was the result of importing the African architectural experience into the domain of the native house.(28) At a later stage, other Africanisms were introduced, such as the emphasis on the long axis and special decorations on the main facade. When these traditions fused with other ideas (such as the Anglo-American grille), the unique Puerto Rican house came to be.(Figure 7) Most examples of the hut type are long gone but their architectural influence is still with us in every solidly closed window and in every street used as a batey (patio) by children and grownups alike.

On the island, cooking was considered a communal affair and, once again, Africanisms transformed the native experience: the Taíno batey became a common area shared by the bohíos that help organize it. Contrary to European plaza standards, this iconic space did not follow any particular geometric layout. It was an informal place to work, chat, cook, play, and, on occasions, dance. It is interesting to note that balconies, the paradigmatic European architectural domestic interior/exterior artifact, are not present in the African-Puerto Rican hut. On the island, Europeans used balconies as visual instruments of order and power. In the countryside they acted as a platform from where the activities of the farm (hacienda) could be inspected. In the city they helped maintain the purdah system, being the only exterior place a woman could venture on her own without male escort. In both cases, they represented something foreign, seldom experienced by the group under study: a place to spend time at ease. The communal batey was the equivalent of the European balcony: it acted both as architectural signifier and signified.

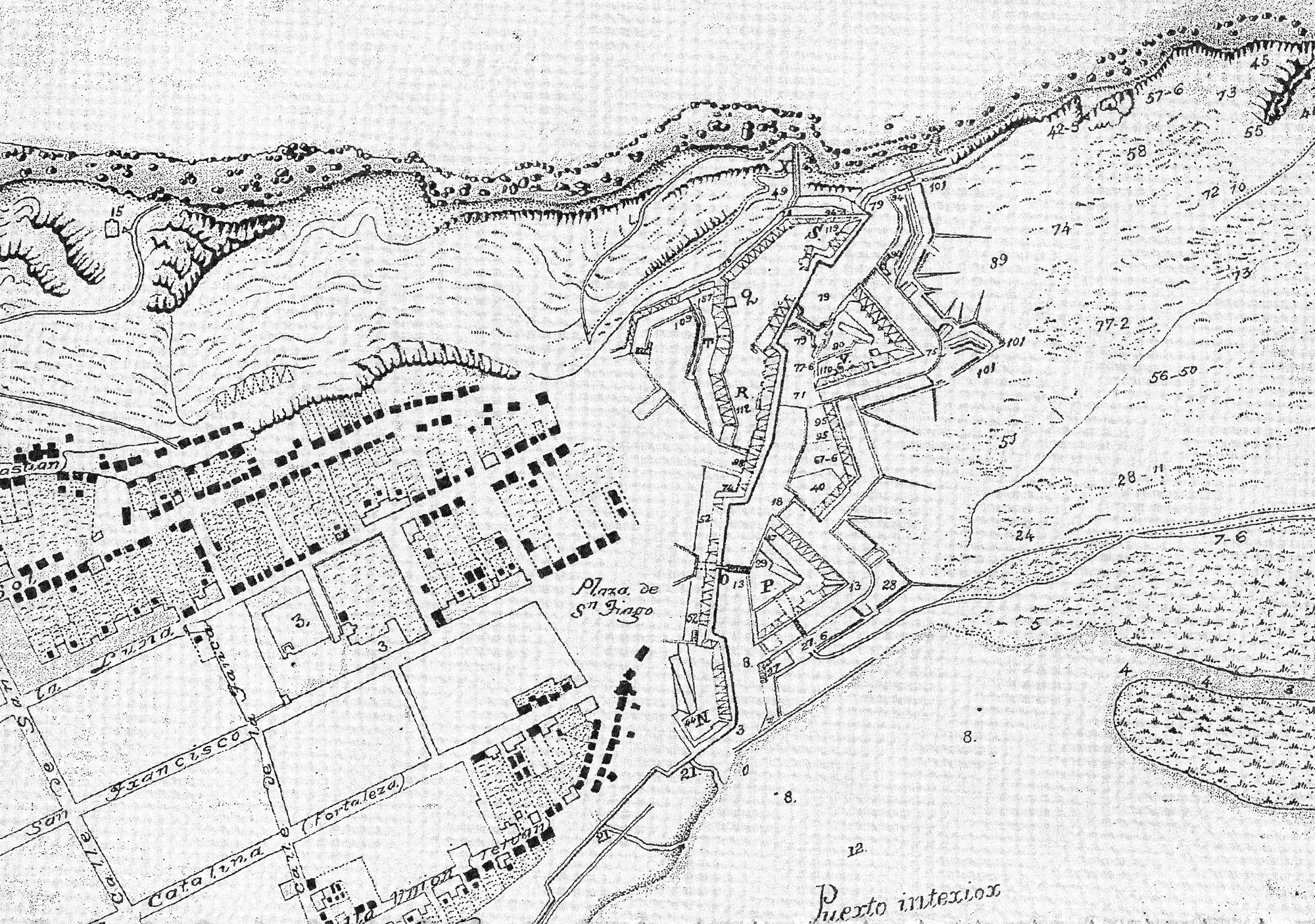

The lack of interest in formal arrangement evidenced in the batey is parallel to the way the group related to the city. Even in the tightly restricted San Juan urban area, the free African-Puerto Rican population chose to express themselves in a different manner. It is interesting to note that the barrio where most lived was distinguished by its own name.(29) In a historic plan of the area, we discover that the individual houses do not follow the rigid grid layout that characterizes the rest of the urban enclave.(30) (Figure 8)

|

Figure 8. This section of the Plano de la Plaza de San Juan de Puerto Rico y sus ymmediaciones... [sic] depicts the area within the old San Juan urban core where African descendants settled. The original plan is dated 1771 and was copied in 1880. (National Archives and Records Administration, RG 71.) |

As the orthogonal arrangement can still be seen today, the domestic units deconstruct the grid. In fact, some houses in the area still have small front gardens, something unheard of in the rest of the city.(31) This is the only preserved physical evidence we have of an urban Africanism on the island, an example of self-expression by a subordinate class. It is indeed curious how, even in the structured and standardized European grid milieu, the group's identity was preserved.

On Things Unseen

Not all things are visible like small front gardens or old photographs of bohíos. There are things unseen regarding the African impact upon Puerto Rican architecture, things for which we lack physical evidence. Contemporary society is said to be guided by phonocentrism, described as a partiality or a favoring of physicality. As a result, physicality—interpreted, on many occasions, as that which is more common—represents truth and reality. The interpretation that something stands for "reality" just because it is more common, makes possible the construction of many different types of binaries: being/not being, presence/absence, male/female, white/black, among others. As Jacques Derrida and others have explained, such binary oppositions favor the "groundly" term or the construction that supposedly articulates the fundamentals.(32) In this manner, distorted conclusions may be reached.

Unfortunately, architectural phonocentrism affects historic preservation methdologies. We tend to ascribe cultural significance to artifacts that we can see or, at the most intangible, to places directly related to events we define as significant or to sites that we believe physically represent historic events. If we do some soul searching, we realize that we are really in the business of preserving tangibles. Yet tangibles are a trap that cause us to believe that only "real things" (as in physical) matter. This is particularly the case regarding architecture.

On occasion, I define architecture to my students using Martin Heidegger's dwelling concept that, naturally, requires presence. It seems to follow that if architecture requires presence, so do historic preservation activities.(33) Is this true? Is cultural significance exclusively tied to the presence of an object? Most of the time, our answer to this last question is yes. That is one of the reasons why many Underground Railroad resources do not qualify as historic resources: we do not have a string of architectural or archeological "things" we can see that are related to them. Curiously, because of our architectural phonocentrism, even when we see, we fail to understand.

Ruins of barracones have a paradigmatic presence in many Puerto Rican haciendas.(Figure 9) While the various names attributed to these structures should alert us, most specialists miss the point regarding the cultural significance of these structures. These places are more than just ruins of storage areas because, in many cases, slaves also used them as dwelling places. The absence of traditional domestic architectural accoutrements clouds our understanding. Interpreted solely as storage areas, they are perceived as architectural symbols of commercial ventures, as examples of specific construction techniques…as everything except the homes of slaves. More importantly, understood as mere storage areas and not as slaves' dwellings, no research activities are undertaken on their other possible histories. As a result, no urgent need arises to preserve the half dozen that still remain on the island.

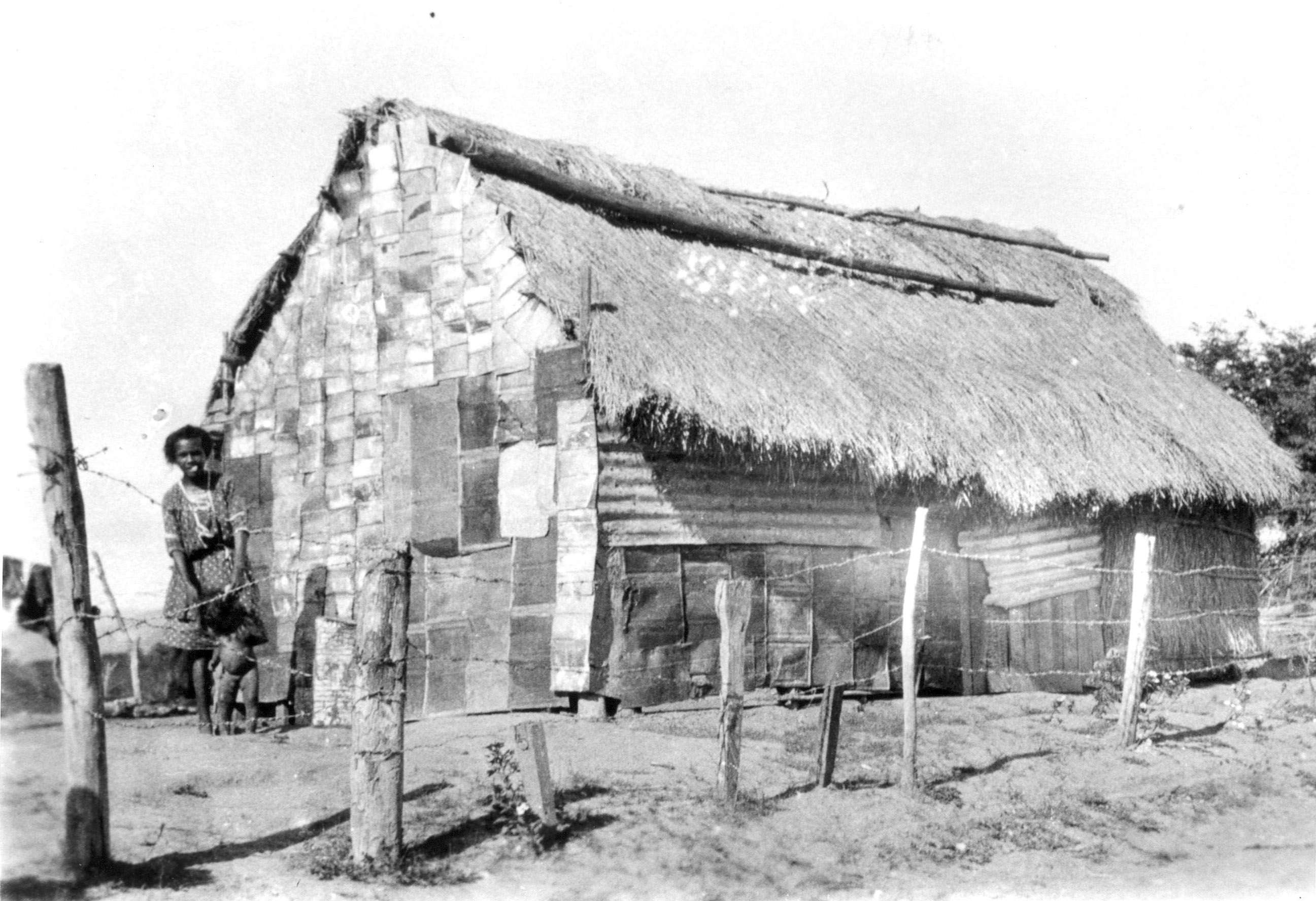

|

Figure 9. Puerto Rican barracones were originally made of the same materials as the bohío. As time went on, metal sheets were used to reinforce the durability of the exterior walls. (Unknown source, circa 1930-1940.) |

All languages, including architecture, are symbols of a mental experience that consists both of sensory and mental perceptions. Architecture is more than a physical artifact and it follows that its "reality" is constructed of more than just stones and bricks or design ideas. There exist supplemental components, like the intangible "baggage" implicit in cultural diversity to mention just one. As preservationists working with the past for the future we have a cultural exigency: we must question traditional interpretations, dislodge assumed certitudes, and deconstruct undivided points of view. How are we to do this? Let us accept Derrida's recommendation and privilege feelings over physicality.

Conclusion

Buildings are a necessity of the metaphysics of presence. Hence their historical significance: they are physically identifiable. Cultural heritage, however, is formed not only of thoughts expressed physically but also of emotions. Furthermore, absent architectural artifacts might still be audible precisely because of their silence. Regarding Africanisms and Puerto Rican architecture, I believe in privileging absence over presence.

Some structures are more than just barracones sitting in the meadows.(34) (Figure 10) Some empty fields are more than just old and now abandoned agricultural areas. These places need to be interpreted in a manner similar to historic battlefields. We preserve battlefields because, for a relatively short interval, something important happened there. Ruins and many abandoned fields are landmarks in the same manner as battlefields.(Figures 11 and 12.) In these places—in every sugar, coffee, or cotton row—a battle was fought every hour of every day, every week, every year, for several centuries. The battle was for things sacred: individual dignity and freedom. These sites, including the few known resting places of the enslaved population, are truly battlefields of honor, where blood and sweat were spent.(Figure 13) Because of this, they are a significant component of Puerto Rican and Caribbean cultural memory.

|

Figure 10. The cotton benfeficiando at Hacienda La Esmeralda, Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico, sheltered the cotton gin. Of special interest is its elegant temple front facade and corner pilasters. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 11. The fields in the Manatí area of Puerto Rico were worked by slave labor in cultivating sugar. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 12. Hacienda La Esperanza, Manatí, Puerto Rico, in spite of its present ruinous state, was one of the most important sugar mills on the island worked by slave labor. The property is owned by the Puerto Rico Conservation Trust. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 13. Unrecognized by most people, this is the site of the slave cemetery at Hacienda La Esperanza, Manatí, Puerto Rico. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Thanks to poetry, Tembandumba's personality and charm are preserved for posterity. The sites and architectural memories that evidence Africanisms present in Puerto Rican architecture are not. We need to preserve them or else risk forgetting one of Puerto Rican culture's most fascinating and elusive histories.

About the Author

Arleen Pabón, Ph.D. and J.D., teaches history of architecture, historic preservation, and architectural theory and philosophy at Florida A&M University (FAMU) and at the University of Puerto Rico. Currently, she is Interim Associate Dean at the School of Architecture, FAMU. In addition to teaching, she runs a consultancy in the fields of historic preservation, historical research, and cultural interpretation, including work for the Republic of Panama's Office of the President (Office of Old Panama City).

Notes

1. This essay is based on a paper presented at the National Park Service's "Places of Cultural Memory: African Reflections on the American Landscape" conference convened in Atlanta, Georgia, in May 2001. The author wishes to thank Professors Rafael A. Crespo and Andrew Chin, Antoinette J. Lee, Brian D. Joyner, and Frederic Rocafort-Pabón for their help and interest.

2. It is possible that "Quimbamba" refers to Quimbombo, the Congo (from Ganga) word for Gondei. Lydia Cabrera, Vocabulario Congo (El Bantu que se habla en Cuba) (Miami: Daytona Press, 1984), 134.

3. Luis Pales Matos, Tuntun de Pasa y Griferia (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Biblioteca de Autores, Puertorriqueños, 1950), 65-66. The poem, "Majestad Negra" (Black Majesty) is taught in grade schools throughout Puerto Rico and most school children know it by heart.

4. Joseph Holloway, ed., Africanisms in American Culture (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991), ix, defines Africanisms as, "[E]lements of culture found in the New World traceable to African origin." Quoted in Brian D. Joyner, African Reflections on the American Landscape: Identifying and Interpreting Africanisms (Washington, DC: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2003), 2.

5. In prehistoric Puerto Rico, the use of stone as a construction material was limited to carved menhirs usually placed around ceremonial areas known as bateyes (parques ceremoniales or canchas). Archeological excavations also show that stone was used in the construction of some roads (calzadas).

6. Christopher Columbus's much-contested letter to the Spanish queen and king mentions that the "houses" were decorated with "nets" and surrounded with "fences," as apparently (only to him) was common in the Valencia region.

7. In Cuba, the bohío is described as a humble structure made of the different parts of the palm tree. Oswaldo Ramos, Diccionario popular Cubano (Madrid: Agualarga Editores S L, 1997), 27. Other construction materials are mentioned in the Diccionario de la Lengua Española, 22nd edition (Madrid: Real Academia Española, 2001). According to this second source, the word bohío is Taíno in origin and describes a rustic architectural artifact made of wood and branches or reeds that has just one opening. (In contrast, the caney, another Taíno word, describes similar structures [cobertizo] without walls.) Note that this is a description of the evolved bohío. The words buhío or bugío were also used in the past. Manuel Álvarez Nazario, El habla campesina del país Orígenes y desarrollo del español en Puerto Rico (Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1990), 330. In this essay, the word bohío is used to both describe the original native and developed forms (which includes Africanisms). The English word "hut" is used interchangeably.

8. Many writers and essayists espouse the idea that the primeval hut is central to the development of architecture. See Vitruvius, De re architectura libri decem; Abbé Marc-Antoine Laugier, Essai sur l'architecture; Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space; Joseph Rykwert, On Adam's House in Paradise, among others. Philosophers and theorists follow suit, including Martin Heidegger and Christian Norberg-Schulz. It is my belief that the bohío is the Caribbean interpretation of the "primitive hut" or choza primitiva. My colleague, Dr. Rafael A. Crespo, refers to the Vitruvian paradigm as the choza rústica. (According to the Diccionario de la Lengua Española, cabaña is synonym for choza.)

9. Dora P. Crouch and June G. Johnson, Traditions in Architecture Africa, America, Asia, and Oceania (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 25.

10. One might question whether or not the full-fledged collective Puerto Rican "personality" had congealed by the 18th century. In my opinion and from an architectural point of view, by this time (two centuries plus after initial European and African presence on the island) the personality was identifiable, as the evolution of special domestic types and the use of the word ibaros [sic] (jíbaro) in this quote suggest.

11. Notes taken from an old manuscript on Caribbean islands kept at the General Library of the University of Havana, Cuba, in 1990. Even though I am unable to specifically name the source (it was presented to me as a bunch of pages with a sort of ribbon loosely binding them), I do remember that there were no page numbers or illustrations, as well as no formal title page. The historic character of the document, written in Spanish, however, was obvious. Since the library strives to preserve valuable documents, it is possible that the manuscript was acquired in this incomplete state. I translated the quoted text.

12. Also known on the island as barracas, cuarteles, cuartelones, and, at times, ranchos.

13. In the Spanish-speaking islands, these structures were known principally as bohío but also as ranchito, casita, mediagua, and mediagüita. Manuel Álvarez Nazario, El habla campesina del país Orígenes y desarrollo del español en Puerto Rico, p 331. Cubans of Congo heritage also used the following terms: nso, sualo, nusako, and kansesa. (Curiously, tombs were known as kabalonga (casa honda) or "deep house.") L. Cabrera, Vocabulario Congo (El Bantu que se habla en Cuba), 46.

14. The post is called pied-bois d'ail. Jack Berthelot and Martine Gaumé, Kaz Antiyé Jan Moun Rété (Paris: Editions Caribéennes, 1982), 85. To "plant" means placing the vertical wooden post (horcón) that serves as a column and sustains the main roof beam (cumbrera or cumblera) and the overhangs (aleros). Arleen Pabón de Rocafort, Dorado: Historia en Contrastes (Dorado, Puerto Rico: Municipality of Dorado, 1988).

15. The island's construction workforce consisted primarily of slaves and prisoners. An estimated 17 percent of the slave trade was destined for the Spanish territories in America, while an additional 40 percent was directed to European-held islands in the Caribbean, which included Spanish colonies.

16. "Descripción de la Isla y Ciudad de Puerto Rico" sent to the King by Diego de Torres Vargas on April 23, 1647, quoted in Coll y Toste, Boletín Histórico, IV, 258. De Torres drew a comparison between the island and Angola. Palm leaves, reeds, yaguas, and guano are

mentioned as local construction materials. (This poses an interesting dilemma for it is well documented that palm trees are not native to the island.) Although some historians mention that mud was used as in Africa, the material as construction material is not associated with Puerto Rico.

17. David Buisseret, Historic Architecture of the Caribbean (London: Heinemann, 1980), 1. Buisseret's description matches those of Fray Iñigo Abbad y Lasierra, Historia Geográfica, Civil y Natural de la Isla de San Juan de Puerto Rico; Pedro Tomás de Córdova, Memorias Geográficas, Históricas, Económicas y Estadísticas de la Isla de Puerto Rico; and Obispo Bartolomé de las Casas, Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, among others.

18. Buisseret, Historic Architecture of the Caribbean, is one of several that credits Europeans with this idea. A notable exception is presented by J. Berthelot and M. Gaumé, Kaz Antiyé Jan Moun Rété since they believe that this morphology is an architectural Africanism. This idea is reinforced by John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993). According to Vlach, the shotgun arrangement is an Africanism. While I do not feel that the shotgun interior arrangement is solely an African contribution, the emphasis on rectangular spatial arrangements seems to be something characteristic to the African architectural experience, even if not unique to it.

19. Many Puerto Rican slaves came from these areas.

20. Notes taken from an old manuscript on Caribbean islands kept at the General Library of the University of Havana, Cuba, in 1990. It is interesting to note the specifics mentioned, such as the use of "Mayagüez bark" (Mayagüez is a town located on the west coast of the island). Humble interiors characterized most domestic establishments on the island. As late as 1899, for example, the "big house" was described in the following fashion—

Even the finest haciendas are meager and barren in their interior fittings. The floors are always bare. The walls have few pictures, though now and then one is surprised to see a clever painting by one of the masters of the modern French school. The usual wall decoration is a pair of Spanish bas-reliefs, in colored plaster or papier maché. Chromos and vilely executed woodcuts often make an appearance, and seem out of place with the oftentimes beautiful architectural finish of the drawing-rooms, whose windows, door less archways are framed in carved woods and relieved of severity by scroll latticework. |

William Dinwiddie, Puerto Rico; Its Conditions and Possibilities (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1899), 147.

21. Henry Louis Gates Jr., Spencer Crew, and Cynthia Goodman, Unchained Memories: Readings from the Slave Narratives (Boston: Bulfinch Press, 2002), 67-68.

22. An arrimao (from the Spanish arrimado) was allowed to work a small plot that belonged to someone else. Payment was part of whatever was produced. Although not considered serfs, their life was extremely harsh as they were subjected to all sorts of uncertainties and economic hardships. It should be noted that in 1899 the institution was still prevalent and described in the following fashion—

House-rent is an almost unknown factor in the country, though in towns many people huddle in to one house and live, amid dirt and disease, at the expense to each family of a few pesos a month. It is customary for landed proprietors to grant to their peons small patches, on the steep hillsides, which are of little value for tillage. This meets the end of assuring their services to the plantation-owners upon demand, with no expense to himself, and secures him the éclat of being apparently a philanthropist. |

See Dinwiddie, Puerto Rico; Its Conditions and Possibilities, 157.

23. Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space: The Classic Look at How We Experience Intimate Places (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994).

24. The most relevant exponents of this theory are Berthelot and Gaumé, Kaz Antityé Jan Moun Rété.

25. There exist all kinds of interpretations about the origins of this word. According to the Diccionario de la Lengua Española, in Andalucía and America, soberado describes an attic (desván). It is possible that some connection was made between an attic-like place and the floor of the house, particularly since many houses were placed on stilts. In 1765, houses on the island were described in the following manner—

Para aquellos días tienen unas casas que parecen palomares, fabricadas sobre pilares de madera con vigas y tablas: estas casas se reducen en un par de cuartos, están de día y noche abiertas, no habiendo en las mas, puertas ni ventanas con que cerrarlas: son tan poco sus muebles que en un instante se mudan: las casas que están en el campo son de la misma construcción, y en poco se aventajan unas a otras. In these days they have houses that resemble pigeon coops built on top of wooden posts with wooden beams and slats: these houses are minimal and consist of a pair of rooms, they are open night and day, and they do not have doors or windows to close them: their furniture is so limited that they can move in an instant: the houses in the countryside have the same type of construction and they are not much better." (Translation by author.) |

Appendix II, 1765 "Memoria de Don Alejandro O'Reilly sobre la isla de Puerto Rico," in L. Figueroa, Breve Historia de Puerto Rico, Vol. I (Río Piedras: Editorial Edil, Inc., 1979), 463-468. According to Manuel Álvarez Nazario, El habla campesina del país Orígenes y desarrollo del español en Puerto Rico, 333, the words originally described the interior generic space and with time came to be associated with the floor surface. There seems to be no definitive interpretation of whether or not the word was used to describe all floors, including dirt-packed floors.

In 1863, a house appearing behind a lady on horseback in the painting Hacienda de Puerto Nuevo by Puerto Rican painter José Campeche, was described as having stilts: Un bohío o casa de campo sobre pilares altos de capá o ausubo. José Campeche 1751-1809 (San Juan: Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 1971), 24-26. It is interesting to note that the word bohío also was used to describe houses in the countryside belonging to the upper social strata. Curiously, similar structures can be found in the northern part of Spain (Galicia). Called hórreos, they are usually used as storage or drying areas.

26. Some years ago, when visiting one of these abodes, I observed that the lady of the house retained her untidy soberao, formed of rough wooden planks. At first, I was surprised with her situation. Now, I understand that the soberao proves that you have a place of your own (even if you are an arrimao and the land belongs to another person). My friend Gloria M. Ortiz, former historical architect for the Puerto Rico State Historic Preservation Office, had a similar experience when visiting the house of a santero artisan.

27. John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery, 165. Susan Snow's quote comes from: Norman R. Yetman, ed., Life Under the "Peculiar Institution": Selections from the Slave Narrative Collection (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970), 61, 144. A former slave described living conditions in the following manner: "Parsons Rogers come to Texas in '63 and bring 'bout 42 slaves and my first work was to tote water in the field. Parsons lived in a good, big frame house, and the niggers lived in log houses what had dirt floors and chimneys, and our bunks has rope slats and grass mattress." Gates Jr., Crew, and Goodman, Unchained Memories: Readings from the Slave Narratives, 81. No mention is made in this case whether or not the dirt-packed floor was a personal choice of the cabin's inhabitant.

28. One of the theses of this paper is that the bohío had a profound influence on Puerto Rican domestic architecture. During the 1940s they still represented a formidable presence—

In sharp contrast to the massive, solid structures of the cities are the bohíos, or cabins of the country people, constructed in much the same manner as the aboriginal homes of the Indians which the Spaniards found on their arrival. The real bohío, raised a few feet above the ground on stilts, is made from palm thatch, with one or at the most two rooms, and sometimes a lean-to kitchen, where cooking is done over a charcoal fire. Furniture is scant and simple, consisting mostly of hammocks, pallets, or perhaps cot beds with colchonetas (quilts) thrown over the springs. Usually the interior walls are brightened by gay pictures from illustrated magazines and newspapers. The crude construction of these humble homes is offset by a profusion of flowers and blossoming vines. Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration, Puerto Rico: A Guide to the Island of Boriquen, 118. |

29. Culo Prieto was roughly located to the east of the San Juan urban core, sandwiched between the city and the only land gate. It was roughly located between Sol, Luna, and San Francisco Streets east of de Tanca Street and west of the San Cristóbal fortification.

30. The plan used for this analysis is an 1880 copy of a 1771 document. The copy was prepared by Francisco J. de Zaragosa and dated December 9, 1880. The American administration copied the copy (provided to them by Mr. Morales on tracing paper) dating it to October 16, 1908. The original third copy is housed at the National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Bureau of Yards and Docks, Record Group 71, "Plano de la Plaza de San Juan de Puerto Rico y sus ymmediaciones [sic]…")

31. In San Juan, street facades typically opened directly onto the street (now sidewalks). During the 20th century, the streets of the area under scrutiny were formally laid. Since some facades did not directly align, small gardens were inserted between the facades and the street proper. This is how evidence of the former deconstruction of the orthogonal grid is preserved.

32. The concept of the "Other" is amply analyzed in Simone de Beauvoir's The Other Sex, Edward Said's Orientalism, and Matthew Frye Jacobson's Whiteness of a Different Color and Barbarian Virtues.

33. Several countries recognize this issue and designate as places worthy of preservation locales that lack definitive presence of artifacts constructed by humans. Unesco recently adopted the International Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. In the United States, recent preservation efforts along these lines include the Trail of Tears, a significant symbolic landscape.

34. At the time that I presented this paper in its original form, I was acting as a preservation consultant for a project that was to be located on the ruins of an early 19th-century cotton beneficiado at Hacienda La Esmeralda in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico. I collaborated with the architect, Abel Misla, in the creation of a new building that frames the ruins in a compatible and sensitive manner. The archeological ruins of the big house were found next to the beneficiado ruins, perhaps reinforcing the idea that the beneficiado might have housed slaves. The rehabilitation project won the premio a la Excelencia de Diseño prize from the Colegio de Arquitectos y Arquitectos Paisajistas de Puerto Rico [Puerto Rican Architects Association].