NPS Photo The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse protects one of the most hazardous sections of the Atlantic Coast. Offshore of Cape Hatteras, the Gulf Stream collides with the Virginia Drift, a branch of the Labrador Current from Canada. This current forces southbound ships into a dangerous twelve-mile long sandbar called Diamond Shoals. Hundreds and possibly thousands of shipwrecks in this area have given it the reputation as the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Visiting the Light StationThe Cape Hatteras Light Station is located near Cape Hatteras, its namesake, which is roughly in the middle of Cape Hatteras National Seashore. The street address is:

National Park Service ClimbingThe Cape Hatteras Lighthouse will not open for climbing in 2026, due to restoration efforts. Virtual ExperiencesA new virtual tour of the Cape Hatteras Ligthouse and webcam are available for visitors to virtually experience climbing the lighthouse and enjoy the breathtaking view from the top.

©Mike Litwin HistoryConstruction of a lighthouse at Cape Hatteras was first authorized in 1794 when Congress recognized the danger posed to Atlantic shipping. However, construction did not begin until 1799. The first lighthouse was lit in October of 1803. Made of sandstone, it was 90 feet tall with a lamp powered by whale oil. The 1803 lighthouse was unable to effectively warn ships of the dangerous Diamond Shoals because it was too short, the unpainted sandstone blended in with the background, and the signal was not strong enough to reach mariners. Additionally, the tower was poorly constructed and maintained. Frequent complaints were made regarding the lighthouse.

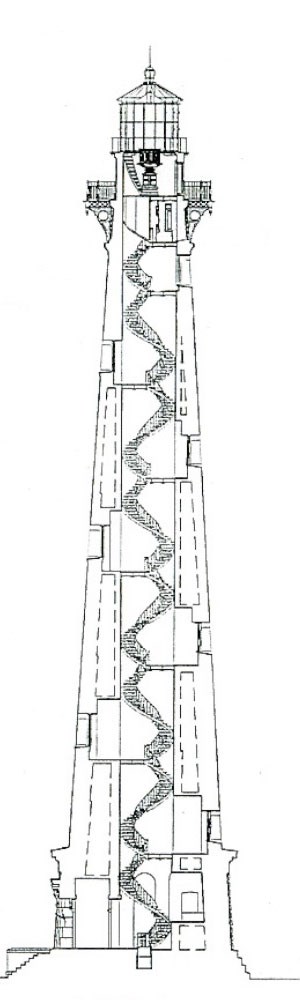

©Mike Litwin In 1853, following studies made by the Lighthouse Board, it was decided to add 60 feet to the height of the lighthouse, thereby, making the tower 150 feet tall. The newly extended tower was then painted red on top of white making the lighthouse more recognizable during the day. At the same time, the tower was retrofitted with a first order Fresnel lens, which used refraction as well as reflection to channel the light, resulting in a stronger beam. By the 1860s, with the need for extensive repairs, Congress decided to appropriate funds for a new lighthouse. The Lighthouse Board prepared plans and specifications and construction on the new lighthouse began in October of 1868. Since the lighthouse was built before the present-day pile driver was perfected, an interesting problem immediately arose. The ground water levels on the Outer Banks are quite high and, therefore, when they began digging out the pit for the lighthouse foundation, it filled with water about 4 feet down. Working with the natural conditions, the foreman, Dexter Stetson, used a “floating foundation” for the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. This meant that layered 6 foot x 12 foot yellow pine timbers were laid crossways in the foundation pit below the water table. Granite plinths (rock layers) were placed on to the top of the timbers. The new lighthouse was lit on December 16, 1870. The 1803 lighthouse was demolished in February of 1871. The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse received the famous black and white stripe daymark pattern in 1873. The Lighthouse Board assigned each lighthouse a distinctive paint pattern (daymark) and light sequence (nightmark) to allow mariners to recognize it from all others during the day and night as they sailed along the coast.

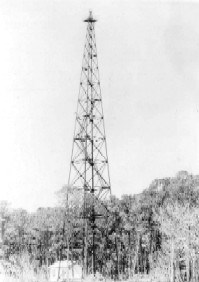

National Park Service The lighthouse is a conical brick structure rising from an octagon-shaped brick and granite base and topped with an iron and glass lantern. It is the tallest brick lighthouse in the United States and measures 198.49 feet from the bottom of the foundation to the top of the pinnacle of the tower. This height was needed to extend the range of the light-beam from the tower’s low-lying beach site. The tower’s sturdy construction includes exterior and interior brick walls with interstitial walls resembling the spokes of a wheel. There are 269 steps from the ground to the lens room of the lighthouse. The Fresnel lens installed in the 1870 lighthouse was powered by kerosene and could be seen approximately 16 miles from the shore. The keeper had to manually rewind the clockwork apparatus each day. The Fresnel lens usually took 12 hours for a complete cycle. When the lamp was electrified in 1934, the manual mechanism was no longer needed. Damaged by vandals, the giant glass Fresnel lens had to be replaced by a modern aero beacon in 1950. Today, electricity provides the rotating power and a photocell turns the light on and off. Due to threatening beach erosion, the Bureau of Lighthouses decommissioned the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in 1935. The beacon was then moved to a skeletal steel tower until 1950. On November 9, 1937, the Cape Hatteras Light Station was transferred to the National Park Service. While the park was not operational at this time, the lighthouse and the keepers' quarters became part of the nation’s first National Seashore.

National Park Service On January 23, 1950, the Coast Guard returned the beacon (250,000 candlepower) to the lighthouse since the beach had rebuilt over the years in front of the lighthouse. In 1972, the beacon was increased to 800,000 candlepower. From the 1960s to the 1980s, efforts were made to stabilize the beach in front of the lighthouse, which had started to erode again. In March of 1980, a winter storm swept away the remains of the 1803 lighthouse and caused significant dune erosion. In 1999, after years of study and debate, the Cape Hatteras Light Station was moved to its present location. The lighthouse was moved 2,900 feet in 23 days and now lies 1,500 feet from the seashore, its original distance from the sea. The Double Keepers’ Quarters, the Principal Keeper’s Quarters, the dwelling cisterns, and the oil house were all relocated with the lighthouse. The National Park Service currently maintains the lighthouse and the keepers’ quarters. The U.S. Coast Guard operates and maintains the automated light. Timeline

NPS Photo Moving the Cape Hatteras LighthouseIn 1999, the Cape Hatteras Light Station, which consists of seven historic structures, was successfully relocated 2,900 feet from the spot on which it had stood since 1870. Because of the threat of shoreline erosion, a natural process, the entire light station was safely moved to a new site where the historic buildings and cisterns were placed in spatial and elevational relationship to each other, exactly as they had been at the original site. While the National Park Service has met its obligation to both historic preservation and coastal protection, the much-heralded move of the historic station, especially the lighthouse, was hotly debated and closely watched.

NPS Photo The LightThe original light was Argand style lamps mounted in front of parabolic reflectors. In 1839, Cape Hatteras was fitted with eighteen 14” reflectors. By 1849, the light had been upgraded to fifteen 21” reflectors. This system used whale oil for fuel and, if in perfect operating condition, produced a medium intensity light that could be seen up to 20 miles. The first order Fresnel lens, installed in 1854, initially burned whale oil as well. However, due to over-hunting, the sperm whale was becoming scarce and, by the 1870s, the US Lighthouse Service was in need of alternate fuels. There is no known record of exactly when the last whale oil was used in a US lighthouse but it is still mentioned in the 1871 Instructions to lighthouse keepers along with colza (wild cabbage or rapeseed) oil. Colza oil was one of the replacements that the US Lighthouse Service considered, but it was difficult to get because it was a low profit crop for US farmers. By 1880, whale oil had disappeared from the scene and, according to the 1881 Instructions to lighthouse keepers, the available fuels were lard oil and mineral oil (kerosene). There was a very short experiment at Cape Hatteras using porpoise oil. It was found to be totally unacceptable and was not adopted. From 1913 to 1934, the light was provided by an incandescent oil vapor (IOV) lamp using pressurized kerosene in a mantle. Official records show that kerosene still fueled the Cape Hatteras light as late 1927. The Fresnel lens Like most late 19th-century lighthouses, this one used a Fresnel lens. Fresnel lenses were manufactured in a series of sizes, or orders, with first order being the largest—over 17 times more powerful than the smallest (6th order). In this case, over 1,000 prisms were used and, all told, about 2,500 lb. of glass and bronze made up the 12 foot tall first order assembly. Triangular prisms projected light into a continuous 360 degree beam, and, in this case, 24 bulls-eye lenses provided the flashes. The light has always been white; at other lighthouses, red and green have also been used (mainly harbor and range lights because color reduces the range of the beam). The original lens assembly, which rotated on a chariot at ½ rpm, was turned by three 150 pound iron weights suspended on a cable and dropping down the center. The cable was wound around a drum in the clockwork mechanism beneath the lens, which worked much like a grandfather clock. Each morning, the weights were slowly cranked by hand to the top and then released at dusk when the lamp was lit, causing the lens to rotate. The gears in the mechanism provided the leverage to turn the 1-½ ton lamp/lens assembly. The speed of rotation could be adjusted by a fan governor in the clockwork. A gentle hand push was used to start the lens rotating but, once it was in motion, it maintained its rotation until the weight reached the bottom of the tower and had to be rewound. Regulations required that the weight be rewound to the top of the tower every morning. In many shorter lighthouses, cranking was needed every few hours. Electrifying the light In 1934, shortly before the light was moved to the tower in Buxton. A 36-inch (nominal) airport beacon was originally used. The current 24-inch (nominal) beacon, type DCB (Directionally Coded Beacon) 224, was installed in 1982. Prior to the installation of the airport beacon, the Fresnel lens only used electricity for the light source but still used the clockwork and weight system to turn the optic. Current optics and bulbs Two separate units, similar to search lights, are mounted side by side facing in opposite directions, and are turned by an electric motor. The beacon is controlled by a photocell, which automatically turns the light on at sunset and off at dawn. Each 1,000- watt bulb (120 volts - same as your house), less than 10 inches tall, puts out an 800,000-candlepower beam focused by two parabolic reflectors. A spare bulb and primary reflector automatically rotate into place when the primary bulb burns out. GE makes the bulbs. They are halogen/argon filled, with a tungsten filament, and cost about $240 each. The mechanism is similar to an airport beacon. The beacon rotates, like an airport beacon. The 'flash' is visible when the beacon points at you. The original Fresnel lens system cast 24 beams, the current beacon projects two. The official range is 24 nautical miles (a nautical mile is 6,080 feet). At night, most vessels in clear weather can see the lighthouse from up to 20 nautical miles at sea. Seen exactly at sea level, the direct visible range is about 15.6 nautical miles. The USLHS standard was to allow an extra ten feet of height to account for the height of the bridge deck, giving 16.2 miles. At night, the glow or loom can be seen when the light is actually below the horizon; in some atmospheric conditions refraction causes the light to follow the earth's curvature, too. These phenomena are also factored in. The range of the lighthouse depends more on height and air clarity than on the power of its beacon.

National Park Service The Lighthouse KeepersThe staff of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse consisted of a Principal Keeper and two Assistant Keepers. The keepers did not live in the lighthouse but, when they were on duty, they would be found in the watch room at the top of the tower. Originally, the Lighthouse Board provided housing, staple foods, medicine, and a salary up to $800/yr. After the 1880s, keepers wore dark blue wool dress uniforms or fatigues. They worked at the lighthouse performing maintenance, repair, and administrative duties. Each keeper was required to stand a four hour watch during the night. The time of these watches alternated daily from keeper to keeper. On one day, the Principal Keeper may take the 8 pm to midnight watch, the 1st Assistant Keeper would take the midnight to 4 am watch, and the 2nd Assistant Keeper would take the 4 to 8 am watch. The following night the Principal Keeper would take the midnight to 4 am watch, etc, etc. The keeper on watch at the end of the night would be responsible for all morning maintenance of the lamp and lens to prepare them for the upcoming night. The keepers' duties included:

The two Assistant Keepers and their families lived in the Double Keepers’ Quarters, built in 1854. The Principal Keeper and his family lived in the small house that was built in 1870.

National Park Service Lighthouse Dimensions

National Park Service Frequently Asked QuestionsQ. How does the height of this lighthouse compare to others? It is the tallest brick lighthouse in the United States. Also, according to the National Maritime Preservation Initiative and F. Ross Holland, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse "…still may be the tallest brick lighthouse in the world.” Q. Has it been in continuous service since 1803? Q. How far was the ocean when the lighthouse was built? Q. How many bricks were used? Q. What other materials were used? Q. How deep is the foundation? Q. How thick and solid are the walls? Q. Who did the actual construction work? Q. Who pays for repair work done to the lighthouse? Q. Who has maintained the lighthouse through the years?

In 1936, the 1870 lighthouse was turned over to the National Park Service. Currently, under a Special Use Agreement, the US Coast Guard maintains the beacon and the NPS is responsible for the building itself. Twice a year, all four light bulbs are replaced, and the mechanism is inspected and lubricated. Q. What has been removed, repaired, or replaced in the structure? Q. What is the circular well at the bottom? Q. What are the vertical rails in the central well? Q. What were the alcoves on the first floor used for? Q. What is the metal tank just above the first floor? Q. What are the numbers on the landing walls? Q. Wouldn't it have been easier to use a rope and pulley to haul up the oil ? Q. How many storms has it survived? Q. Why is the tower leaning? Q. Why is there a lighthouse here? Q. How did the Diamond Shoals get their name? Q. How many lightships have there been at Diamond Shoals?

Q. What is the "Texas" tower? Q. Why are there so many lighthouses in North Carolina ? Q. Is the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse still a functional navigational aid? Q. With today's navigational technology, is it still a useful aid-to-navigation? Q. Why is it painted with black & white stripes? Along the Outer and Core Banks of North Carolina, the Currituck Beach Light is unpainted, red brick; Bodie Island is banded black and white; Cape Hatteras is black and white spiral stripes; Ocracoke is white; and Cape Lookout is black and white checkerboard. No evidence has been found to indicate that the checkerboard or diamond pattern was originally intended for the Cape Hatteras Light at Diamond Shoals, despite a popular folk story that some bureaucrat messed up the work order. Q. What is meant by the term “daymark” and how does it apply to lighthouses? Generally, the shapes of the tower and dwelling, the advertised color and the geological background such as cliffs, rocks, hillsides, etc. provide adequate data to the mariner to assist with location determination. Towers can also be painted, often in solid colors that contrast with their natural backgrounds making them more visible. So, a lighthouse that is built of stone on a rocky island would most likely be painted white; a lighthouse near a town with numerous white buildings would probably be painted red. However, problems can occur in areas such as the central/southern Atlantic coast of the United States. In general, the coast is topographically quite flat with few, if any, outstanding natural features to assist the mariner. Compounding this issue, the tall coastal towers, built primarily between the 1850s and 1870s, were virtually identical in appearance from a distance at sea. Therefore, to make them identifiable, they each received distinguishable daymarks—usually paint—though some towers were left unpainted. Only certain colors—black, white and red—were used because these are the ones that would stand out the best against the background. Therefore, along the Outer Banks, the tall coastal lighthouse daymarks are: Currituck Beach Light - unpainted red brick; Bodie Island - banded black and white; Cape Hatteras - black and white spiral stripes; and Cape Lookout - black and white checkerboard. Q. Has the Cape Hatteras lighthouse always been black and white spiral striped? The 1803 sandstone tower appeared to be white. This may have been due to the natural color of the stone or a whitewash coating. This changed when the tower was extended with a brick addition in 1854. The lower 70 feet of the tower remained white and the top 80 feet was red. It was probably red on top to contrast with sky and white on bottom to contrast with the vegetation. It was painted with a cement-based brick wash. The 1871 Report of the Lighthouse Board indicates that, when it was first painted, the top part of the current tower was painted red and the bottom part white. Other reports say that the whole tower wasoriginally red. In any case, the stripes were painted in 1873. There are two black and white stripes on the tower, each stripe circles the lower tower 1-1/2 times, and all are wider on the bottom than on the top. It is not known exactly how the stripes were laid out, but it could have been done using a combination of pre-calculated dimensions, plumb bobs, and taut lines. Originally, the keepers painted the tower using bosun’s chairs, taking up to 4 months every 6–10 years. Modern painting contractors use a window washer type platform. From 1936-1950, the official tower was a steel structure, though many mariners still used the 1870 lighthouse as a daymark. Q. How can lighthouses be told apart at night? |

Last updated: January 7, 2026