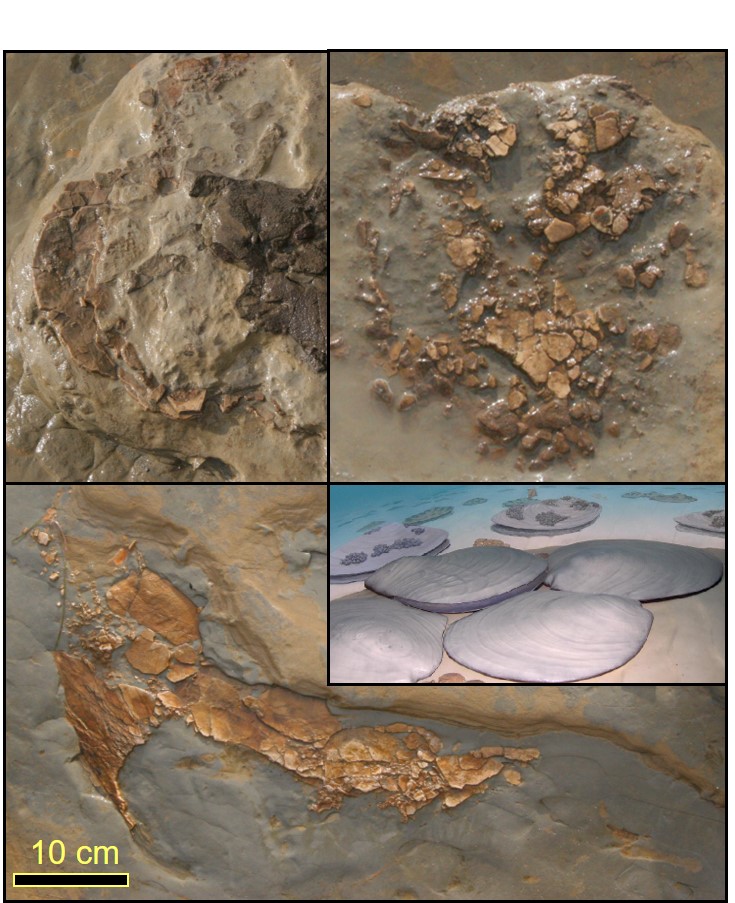

One such fossil, called an Inoceramid, was a large, thin bivalve related to modern-day clams. These animals lived on the sandy bottom filter-feeding for plankton. Different species of Inoceramids were prominent in all of the world’s oceans, but went extinct near the end of the Cretaceous period. The fossilized top shells of these bivalves can be seen today, scattered throughout the Point Loma formation, which is composed of rocks 72-76 million years old. The fossils are about 10-20 cm wide and look like bubbly crusts embedded into the tidepool cliffs.

Photo Credit: Dr. Stephen Schellenberg – Inoceramid fossils in the Cabrillo National Monument tidepools with an artists’ rendering of what these bivalves likely looked like.

Other prominent species dwelling in the soft sediments of the Cretaceous ocean were ancestors of modern-day ghost shrimp. These creatures, called Ophiomorpha and Thalassinoides, lived their entire lives in long, narrow burrows they dug. At the time of their existence, these burrows were a few kilometers under the sediment, but today, they can be seen on the surface. These fossils are known as trace fossils because they are not remains or impressions of the animal, but rather the remains of their day-to-day lives. Ophiomorph and Thalassinoid tunnels can be distinguished from each other by their texture. Ophiomorph burrows are lined with fecal matter to reinforce the structure and prevent them from collapsing. This created a rough texture and a dark color that today looks like an iron rod embedded in the sandstone. Thalassinoid burrows, on the other hand, are usually thinner and much smoother. These fossilized burrows are scattered throughout the Cabrillo tidepools, and often go unrecognized as visitors walk on top of them.

NPS Photo/McKenna Pace – fossilized burrows of Ophiomorpha (left) and Thalassinoides (right) in the Cabrillo National Monument tidepools.

Finally, are the trace fossils of the irregularly-shaped, tube-footed ancestors of sea urchins, called Scolicia. These burrowing echinoids were deposit-feeders that scoured the sediments for organic material to eat. As they travelled about, their tube feet moved sediment from the front to back of their path, creating a line of crescent-shaped ridges along their burrow. In the Cabrillo tidepools, these trace fossils can be seen on many of the same walkable ledges as the Ophimorpha and Thalassinoides.

NPS Photo/McKenna Pace – fossilized Scolicia burrow on the cliff’s edge at Cabrillo National Monument.

Next time you travel down to the tidepools, I encourage you to look for some of the fossilized remains of what once was. The side-by-side pairing of the living and once-living reminds us that life on earth exists in a delicate balance. Years from now, what will our tidepools look like? What kind of fossils will our descendants find?

*A special thank-you to Dr. Stephen Schellenberg, who provided the information found in this article at his Naturally Speaking lecture on December 14. If you would like to become a Foundation member and attend future members-only events, visit the CNMF website at: https://cnmf.org/shop/membership/

**Our next Naturally Speaking lecture, entitled Nature in Balance – Managing the National Parks, features Cabrillo National Monument Superintendent Andrea Compton. This lecture will highlight the difficult task of managing resource protection with visitation within the National Parks system. The event will be held January 18 at 6 pm in the Cabrillo National Monument Auditorium. RSVP to this CNMF members-only event here: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSfIThLgmG1lMDHS4V2K4tKVrUW0qH0wR48HPmv3BPu4TYOf6g/viewform

NPS Photo/Nicole Ornelas – guest speaker Dr. Stephen Schellenberg presenting to Cabrillo National Monument Foundation members on December 14.