|

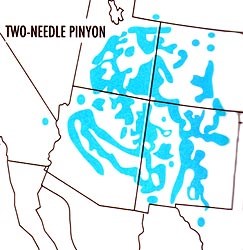

Common Names: Colorado Pinyon, Two-needle Pinyon, "Pinyon Pine." Scientific Name: Pinus edulis Size (height & diameter) English & Metric: 15-35 ft (4.6-10.7 m) tall, 12-24 inches; (.3-.6 m) in diameter Habitat: Dry open land 5000-8000 ft (1500-2500 m) above sea level Flowering Season: N/A not a flowering plant Range: Colorado Plateau

lee dittman The Colorado Pinyon with its crooked trunk and red-brown bark, is found in dry, rocky places at elevations of 5,000-8,000 ft. Growing where yearly precipitation is only 10-20 inches per year, they depend on their enormous root system to harvest enough water to survive. This root system is at least as large as the above- ground part of the tree. Tap roots stretch down 40 or more feet into the soil, while lateral roots stretch as far horizontally. This is the reason you don't see Colorado Pinyon clumped together very often because they must spread out to accommodate the root system requirements. This pine has a very slow growth rate: a 10 foot tall tree could be 80-100 years old.

lee dittmann Plant Lore: Popularly called "Pinyon Pines", there are four species of pinyons in the American Southwest. The name pinyon or piñon is Spanish for "pine nut", so the name "Pinyon Pine" could be translated as "Pine Nut Pine"- a somewhat redundant moniker. Better to just call all the various species of nut pines "pinyons" and identify them more specifically, as needed, such as Colorado Pinyon, or Two-Needle Pinyon.

nps photo Like Limber Pines, Pinus flexilis, pinyons are dependent on Pinyon Jays and Clark's Nutcrackers for their survival. These birds are equipped with a crowbar-shaped bill and throat storage pouches so that they can harvest, transport and cache large quantities of pine nuts. To insure survival through the most difficult winters, a single bird will need to cache up to 30,000 nuts. Seeds from the caches that are not eaten during the following winter, will germinate and sprout another generation of Colorado Pinyons. Evolutionary biologists theorize that this symbiotic relationship has been evolving for a very long time. Initially, Pinyon Pines probably produced tiny pine seeds with wings like most other pines, relying on the wind to spread the next generation. As these two species of cache-making birds began to specialize in pinyons, the trees that produced less wing and larger, more nutritious seeds were rewarded by having increasingly more of their seeds well-planted by the birds. Once the relationship was cemented, producing any wing on the seed was a waste of energy because the trees could now trust the wings of the birds to get the seeds where they needed to go. Lastly, when the seeds became increasingly nutritious, they needed to be protected from uninvited guests like rodents and other birds. So as heavy hulls and rock-hard cones were developed, the birds had to produce a crowbar-like tool to pry the cones open and crack the hulls; hence the heavy, long, and slightly curved bill these two birds have in common. Now these trees and birds are mutually dependent. Without these two species of birds, pinyons would no longer be able to reproduce. These highly-specialized, large, heavy nuts would never get transported far enough away from the parent tree to be able to find their own supply of sunlight, water and nutrients without competition from the parent. The obligation of the pine nut lover is to protect this fragile relationship. Surprisingly enough the most destructive thing you could do is to attempt to feed one of these birds, even if you are only offering them a pine nut. Parent birds that learn to accept handouts from humans don't bother teaching their young how to process pine nuts the hard but natural way. The young will ultimately die of starvation once the tourist and their handouts are gone. Fewer nutcrackers and jays will mean fewer pinyons, which means even more expensive pine nuts. If for no other reason than for the sake of affordable pesto... Please do not feed the wildlife.

NPs iMage Pinyon Pines are seldom seen above the rim and are most common "where the rock is gray in color" meaning down in the valleys below Bryce Canyon. Cones begin to open in September and nuts can still be found into November as long as the birds don't beat you to them. Further Reading: Lanner, Ron M. 1996, Made for Each Other: A Symbiosis of Birds and Pines. Oxford University Press. |

Last updated: September 4, 2021