|

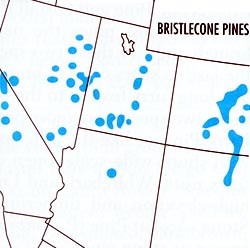

Common Names: Great Basin Bristlecone Pine, Intermountain Bristlecone Pine Scientific Name: Pinus longaeva Size (height & diameter) English & Metric: 40-60 ft. (6-12 m) tall, trunks 12-30" (.3-.8 m) in diameter Habitat: Exposed dry rocky slopes and ridges between 6500-11,000 ft (2280 - 3500 m) Flowering Season: N/A not a flowering plant Range: Mountains of Utah and the Great Basin.

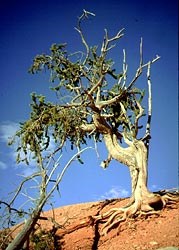

Bristlecone Pines (Pinus longaeva and Pinus aristata) are among the oldest living organisms on earth. Clone-creating plant species like Quaking Aspen live to be much older if you age their root systems. Bristlecones are only found in six states, Utah included. The oldest LIVING tree is called "Methuselah" and is 4,765 years old. This tree is nearly 1,000 years older than any other bristlecone alive today. It lives in a secret location in the White Mountain range of eastern California. The oldest known tree named "Prometheus" was cut down in 1964 by a doctoral student. He was studying climate change as expressed in receding glaciers whose historic size could be measured by influence on the growth rings of nearby ancient bristlecones. This happened in what is now known as Great Basin National Park. The tree was later confirmed to be almost 4,900 years old. Bristlecones have 5 needles per fascicle, and can grow to be 40-60 feet in height (under most favorable conditions.) Often they will die in portions. As the roots become exposed they will dry out and die. The tree directly connected above those roots will eventually die as well. The remainder of the tree will continue to live. This is among the causes that create the twisted tortured look of the trees. It also may prompt the question "why do they take so long to die?" as opposed to "why do they live so long?" Bristlecone pine is also known as "Wind Timber", "Hickory Pine", "Krummholz" and "Foxtail Pine." It is a member of the group of pines known as foxtail pines, because of the shape of the branches and the way the needles stay attached all the way up the limb. The limbs look like small foxtails. In recent decades, two species of bristlecone have been distinguished. Pinus longaeva is called the Great Basin Bristlecone. Pinus aristata is the Rocky Mountain Bristlecone. The biological distinction is based on the numbers of resin ducts per needle, which are difficult to see even with a powerful hand lens.

The Bristlecone Pine was first documented by F. Cruetzfeldt, a botanist with the Pacific Railway, in 1853. The group he was with was looking for a new route over the Rocky Mountains, and found themselves in the Cochetopa pass in Colorado (now, Colorado State Hwy 114). Cruetzfeldt wrote in his journal that the area was "covered with a scanty growth of pine". He collected one branch and no cones, (bad botanical sample). Later, as the group moved into eastern Utah, they were attacked by a group of Ute Indians, and the entire party was killed. One of the accounts claimed that by the time the bodies were found, most had already been eaten by wolves. This is now known as the "Gunnison Massacre" after the leader of the group. Needless to say, the branch sample and all of Cruetzfeldt's notes were lost. Governor Brigham Young, having heard the rumors of the massacre, was able to procure the sample and all of Cruetzfeldt's notes back from the Ute tribe, and had them sent East where the species was classified. The Bristlecone Pine was "rediscovered" by Dr. Edmund Schulman in the mid 1950s. In fact, it was his party that found and dated the "Methuselah" tree. He reported his findings to the National Geographic Society in 1958. This article brought much fame to the "Schulman grove" and it was set aside by the USFS. The tree is used heavily in the science of dendrochronology, where tree rings of known ages are compared against environmental conditions and a history of previous environmental conditions is recorded. Because the trees are thousands of years old, we can understand what the environment was like thousands of years ago, just by comparing the tree rings. The tree is also noteworthy because the needles stay on the limb for over 40 years, unlike most other pines, which shed their needles every few years. This is important, because the tree can go through periods when it does not grow at all. At such high elevations (8,000-11,000 ft), there are years when the environment does not thaw. This prevents the tree from putting on a new year's growth (both foliage and cambium rings.) By keeping its needles longer, the tree doesn't lose all of its foliage without having the opportunity to grow new needles. It also means that a tree with 900 obvious rings may be significantly older. Great longevity is also insured by highly resinous wood which helps prevent the trees from desiccating in the hot, dry temperatures. This resin also helps shield the bristlecones from insects and harmful bacteria that prey upon many other, more fragile trees.

Like all plants in National Park Service areas the Bristlecone is protected. Unfortunately the selfish tradition of collecting anything unique has caused many agencies who protect Bristlecone Pines to keep secret the age and location of their older trees. This is also the case at Bryce Canyon National Park. This resource management attempt to protect ancient trees results in punishment of the visiting public in general. Think about this situation the next time you complain about a rule you feel is too restrictive on public land. Is there something that you can do to insure that other privileges are not also lost?

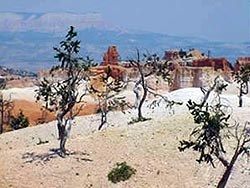

You can see Bristlecone Pine trees on the Fairyland Loop trail, as well as the Bristlecone Loop trail at Rainbow Point. They are also scattered about the park, on the Peekaboo Trail and in places along the Rim Trail near Inspiration Point. Usually, you won't find them in the interior of the park, only near the rim. The oldest bristlecone is found at Yovimpa Point on the Bristlecone Loop Trail, and is estimated at over 1,600 years old--a mere youngster!

Further Reading: Buchanan, Hayle 1992. Wildflowers of Southwestern Utah. Bryce Canyon Natural History Association. Bryce Canyon, Utah Fisher, Andy 2000. Bristlecone Pine Ask Me About. Bryce Canyon National Park. Lanner, Ron. & Rasmuss, Christine. 1988. Trees of the Great Basin: a Natural History. University of Nevada Press. Little, Elbert L. 2001 National Audubon Society Field Guide to Trees - Western Region. Random House Inc. New York, NY Stuckey, Martha & Palmer, George. 1998. Western Trees: A Field Guide. Falcon Publishing, Inc. Helena, MT |

Last updated: March 5, 2024