NPS Tribute to the Unknown Mormon Pioneer(Author’s Note: Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saint are commonly referred to as “Mormons”. This story uses a fictional character to portray Bryce Canyon’s pioneer history. Please protect our pioneer inscriptions by NOT carving on trees today. John D. Russell) The Mormon pioneers spent long, lonely summers tending sheep and cows in present day Bryce Canyon National Park. While killing time and reflecting back on his life, a bald-headed, gray mustached pioneer carved a horse’s profile, a man’s profile, and the four playing card suits in an aspen tree. This pioneer not only glorified some favorite pastimes, but reflected on how he had beaten the odds in the game called life. This Mormon pioneer, acting in the name of God, had played to win against the harsh elements of the Utah wilderness or “The Land Nobody Else Wanted”. Sometimes the pioneer had won, sometimes the wilderness won. Ultimately, this pioneer cooperatively: tamed and diverted wild rivers, prevailed against “wild men”, harvested timber in foreboding forests full of wild beasts, and raised livestock in inhospitable ranges. What were the stakes in this game of chance? What has been won and what has been lost?

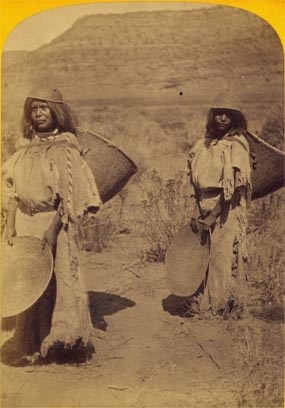

NPS In his younger years, this pioneer had witnessed American Indian women harvesting Indian rice grass. Local American Indians ground the seed into meal or flour and made bread from the flour. However, by the 1860s, this valuable food source became extremely scarce. Livestock grazing nearly eliminated this and other valuable food sources from the Utes’ traditional “hunting and gathering” range. Chief Black Hawk “forced by the starvation of his people” organized area tribes to raid pioneer settlements. Frightened Mormon pioneers retaliated with some horrific acts. Later, the James Andrus Military Expedition of 1866 chased marauding Navajos through present day Bryce Canyon National Park. Pioneers, fearing further American Indian uprising, abandoned their homes and communities from Gunnison to Kanab by June 1866. During the Black Hawk War, American Indians killed seventy whites; whites killed countless American Indians. Black Hawk and other Indian Chiefs made peace with their Mormon neighbors during the late 1860s. Pioneers re-settled most of the abandoned communities during the 1870s. The Ute, Paiute and Navajo were displaced to reservation lands.

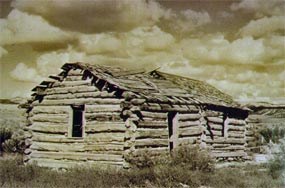

NPS Ebenezer Bryce constructed a logging road in the Bryce Amphitheater. Local people commonly referred to this road as "Bryce's Canyon". Other pioneers constructed more logging roads and sawmills nearby. Can you imagine the pioneer's joy of having a real log home after spending up to a year in a wagon? The pioneer viewed timber as a "crop". The Pioneer extinguished all forest fires to protect this valuable crop of timber. This pioneer's grandchildren would live to see the unintended consequences of a hundred years of fire suppression. Fire has always played a dynamic and necessary natural role in maintaining healthy ecosystems. Prior to this protection, a Paiute or this early settler looked up to the Paunsaugunt Plateau and spotted two or three small fires. The overgrown Ponderosa Pine forest would gently burn back to a spacious, healthy Ponderosa Pine forest with palatable grasses. Nearby aspen groves were revitalized by fire. Since then, the thickening forest has crowded out sun-loving aspens, wildflowers, forbes and grasses and allows "only those shrubs that sprout through thick litter and grow in dark heaviness" to exist. Also, extending civilization into wilderness left little room for "wild beasts". If you heard the big, bad wolf howling in your backyard, how would you react? The pioneer exterminated predators like the Gray Wolf and the Grizzly Bear. If you felt disease threatened your livelihood, how would you react? The pioneer routinely killed American Beaver, Desert Bighorn Sheep, Mule Deer, Rocky Mountain Elk and the Utah Prairie Dog to protect their domesticated cattle and sheep from disease and/or perceived harm.

NPS The Tropic Ditch near the Mossy Cave Trail in Bryce Canyon National Park has run for over a century. Mormon farmers diverted water from the East Fork of the Sevier River near Tropic Reservoir to irrigate fields around Tropic City. This pioneer labored feverishly with primitive tools for 15 miles over three years to construct the Tropic Ditch. Similar projects had resulted in failure. Yet, without this victory, pioneer settlements around Tropic would be impossible. Previously, water had both cursed and blessed the pioneers. Can you imagine the pioneers' dismay when flash floods washed away their crops and buildings and forced them to abandon their hometown? Can you imagine making the difficult choice of either; starving to death in your hometown or moving elsewhere? How about taking your home apart - log by log and then putting the pieces back together again, so you could be closer to a reliable water source? One pioneer described the celebration of the life-giving Tropic Irrigation Ditch this way: "A country, they said had been born, and so they sang out praises and prophesied great things about the future…We danced all night till the broad daylight."

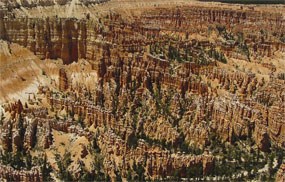

NPS The Pioneers grazed cattle and sheep despite the Bryce badlands, unpredictable weather and vanishing grasses. Pioneer livelihood and survival depended on their success in overcoming these and other obstacles. Ebenezer Bryce reportedly described his canyon as a "hell of a place to lose a cow". You may empathize with Bryce's frustrating search by looking at the labyrinth of hoodoos at Bryce Canyon National Park. Additionally, Tropic did not always live up to its name. For example, the May blizzard of 1900 left three feet of snow on the range. 300 sheep died; trapped in the deep snow. The sheepherders dragged trees behind oxen teams, like a snowplow, to rescue the remaining hapless animals. Drought and overgrazing combined to afflict our pioneer stockman in 1903. "The once rich meadows on the mountain had turned to dust beds. Herds of sheep were bedding by the streams and dying along the banks. Bones of cattle bleached on the dry benches…Poison weeds that grew after the better feed was gone added to the death of the starving cattle." Later that year, President Roosevelt created forest reserves to protect the remaining forests and watersheds of the area.

For the first time in his life, the unknown Mormon pioneer thought about his winnings and losses in the game called life. The desert "blossomed like a rose". Civilization had been carved out of the wilderness. American Indians no longer threatened homesteads. Towns, ranches and farms covered the valleys. Cowboys, hunters and lumberjacks tamed the forest and the range. But what had been lost? The shame of having killed countless, starving American Indians with the survivors being "Americanized" on reservations. His children never knowing the wildness of the land: no howl of the Gray Wolf breaking the silence, no mother Grizzly Bear sow with her cubs, no Desert Bighorn Sheep, no large herds of Mule Deer or Rocky Mountain Elk, no friendly Utah Prairie Dogs barking from their mounds, no wild forests, no tall grasses rubbing under his horse's belly and few wild rivers and streams left with few American Beavers building their dam. In addition, his children would inherit sickly rangelands, forests and watersheds regulated by the national government. Then the pioneer wondered, "If I had to play the game of life again, would I do anything differently?" Further Reading: Carlton, Culmsee. 1973. Utah's Black Hawk War. Utah State University Press. Logan, UT Chesher, Greer. 2000. Bristlecone Loop at Rainbow Point Trail Guide. Bryce Canyon Natural History Association. Bryce, UT Newell, Linda & Talbot, Vivian. 1998. A History of Garfield County. Garfield County Commission. Utah State Historical Society. Salt Lake City, UT Scrattish, Nicholas. 1985. Historic Resource Study Bryce Canyon National Park. National Park Service. Denver, CO Stegner, Wallace. 1970. Mormon Country. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, NE Wenker, Chris. 2004. Bryce Canyon National Park Archeology of the Paunsaugunt Plateau Intermountain Cultural Resource Management Professional Paper No. 69. National Park Service. Denver, CO Woodbury, Angus. 1997. A History of Southern Utah and Its National Parks. Zion Natural History Association. Springdale, UT. |

Last updated: July 24, 2020