SEINet Arizona – New Mexico Chapter You can learn more about the plant communities that these species belong to here, and use this page to learn more about the plants as you observe them. Note that not every single species may be present or noticeable along the trail (or in the monument) at a given time. You can also visit this page to learn more about the Heritage Garden located nearby, which seasonally features Pueblo crop varieties similar to those that were grown here in past times. All photos on this page are courtesy of SEINet Arizona-New Mexico Chapter, except as noted. Their database for Aztec Ruins National Monument can be visited here. How To Use This GuideThe plants of this guide are organized alphabetically by common name, according to the sections: grasses, herbaceous plants, and succulents (cacti and yucca). Although this guide is organized by common names, often it is easier to distinguish a species of plant by its latin name because there can be many common names for one species of plant. Another note is that the Native Plant Trail represents a group of plants that are found within different ecosystems in this landscape and won’t necessarily be found in an ecozone that they are not ecologically adapted for. An example of this would be plants found in the riparian zone such as willow, which will not be growing in areas of the semi-desert shrub step zone with sage brush and yucca without ample water present.As the Natural Resources Program of Aztec Ruins National Monument, we politely request that harvesting of plants not occur on the monument unless (and only if) permission is gained in advance. If, somewhere besides the monument, you have permission to collect, we advise you to take precaution in the harvesting and use of wild native plants because of potential health and safety risks. This is a non-comprehensive tool aimed at introducing and educating the public to wild native plants of the San Juan Basin; furthermore, more specific information regarding the medicinal uses of the plants mentioned in this guide should be gathered from other sources; the list of references used in creating this guide is at the bottom of the page. It is important to recognize that the origins of ethnobotanical knowledge are linked to indigenous communities all around the world; and that for many indigenous cultures there continues to be a shared relationship with the plant communities they have been interacting with for thousands of years. Lack of knowledge surrounding the harvesting of native plant communities has in some cases resulted in overharvesting throughout the country. A good rule of thumb is to learn about best harvesting practices for your area as well as plant communities that are particularly vulnerable or at risk. It is part of the mission of the National Parks “to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Parks System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” Based on the park’s mission, it’s our goal at Aztec Ruins to preserve native wild plant populations within the natural landscape, and to help educate the public about the work of preserving our public lands. As the Natural Resources Program, we hope that in reading this guide you will walk away having learned something new. Grasses

Alkali muhly grassMuhlenbergia asperifoliaCharacteristics: Alkali muhly grass is a perennial bunch grass that propagates and spreads via creeping rootstalks, known as rhizomes. It and other members of the genus Muhlenbergia can be distinguished by having single-flowered spikelets, with the glumes that form the husks of its grains (like those found on wheat) being unequal in size. Ecology and Distribution: The presence of this grass is a good sign that there is ample water. It can be found in meadows, particularly alkaline ones, along sandy washes, on rocky and sandy slopes, and near hot springs. Muhly grass grows at elevations ranging from 4000 to 6500 feet, and can be found throughout North America (except for the far north and the southeastern United States) and down to South America. Ethnobotanical Uses: Different indigenous groups have used the seeds and leaves of this grass and its relatives. The seeds can be ground into flour to make bread, while the leaves were used as brooms and other tools.

Alkali sacaton grassSporobolus airoidesCharacteristics: This grass and other members of the genus Sporobolus are often known as "dropseed", since the seeds easily fall after maturing (if, for example, an animal brushes against the plant). The flowers normally bloom from May to October. Like muhly grass, sacaton grass has single-seeded spikelets with unequal-sized glumes, and grows as a robust, hardy perennial bunch grass. The plants have stiff stems, a knotty base, and rolled, drooping leaves with large fountain-like growth forms. Distribution and Ecology: Alkali sacaton grass is found throughout western North America at elevations from 2500 to 6500 feet. It prefers alkaline soils and grows in sandy plateaus, washes, bottomlands, and flats. Ethnobotanical Uses: Even as far back as the Archaic Period (2000 BCE-200 AD), long before the ancestral Puebloans built Aztec, this plant was an important source of grain for people of the Four Corners region. Often collected during times of famine, the seeds were made into bread or porridge after being cooked in heating pits.

Blue grama grassBouteloua gracilisCharacteristics: Blue grama is a common native grass with a distinctive inflorescence (flowering head) shaped like human eyebrows or eyelashes. It produces these flowers from July to October. The blue-green leaves of this plant grow in dense tufts, becoming curly and straw-colored when they dry out. Distribution and Ecology: Growing from Canada south to central Mexico, blue grama can be found on rocky slopes, forest clearings, and grasslands at elevations from 4000 to 8000 feet. It is considered a soil-building or "pioneer" species, meaning that after an area is disturbed (for example by fires, landslides, or human activity), it is one of the first plants to grow. The grass will provide ground cover and break the soil up so that forbs (herbs and wildflowers) and shrubs can begin growing. Ethnobotanical Uses: Bunches of blue grama can be tied together to make brooms and hairbrushes, and the plant can also be used in basketmaking and ceremonies. Since the introduction of European livestock like cattle, it has become an important forage grass.

Indian rice grassAchnatherum hymenoidesCharacteristics: Rice grass is distinguished by its open flowering branches (panicles), as well as its seed pods, which are dark-colored and slightly kinked. The flowers appear from May to August. Distribution and Ecology: This grass grows in dry, well-drained soils throughout the western United States and Canada, as well as northern Mexico. It can be found at elevations from 3500 to 6500 feet. Ethnobotanical Uses: During both prehistoric and historic times, Indian rice grass has been an important source of food. Archaeological sites in the Four Corners region, including those here at Aztec, often yield rice grass seeds, sometimes in coprolites (preserved human excrement). The seeds were likely used for food during times of famine or poor crop yields; in addition, the rice grass seed harvest began in mid-June, when other food sources may not have been as plentiful. The seeds, which are rich in protein and calories (about 120 calories per ounce of seed), were ground and made into warmed porridge, bread, cakes, or gruel. The flour was also combined with cornmeal to supplement it, particularly when corn yields were low, and made into steamed balls. Herbaceous Plants

Blanket FlowerGaillardia pinnatifidaCharacteristics: Blanket flower is a perennial herb with a large, roundish head of distinctive, showy red-orange disc flowers surrounded by yellow rays, each with three lobes. The flowers bloom from April to October, and the stems and leaves are grey-green. In Colorado and Wyoming, there is a species of moth (Schinia masoni, pictured below on Gaillardia aristata) that has adapted red and yellow coloration in order to better blend in with the colors of different species of blanket flower. The relationship that the moth and flower share is mutualistic, meaning that both species benefit. The moth hides from predators in the flowers, and it in turn pollinates them and helps them reproduce. Distribution and Ecology: Blanket flower is found in limestone soils on mesas, plains, and in open forest, from 3500 to 7000 feet. It is found in the Four Corners states, stretching east to New England, south to Texas and Mexico, and north into Canada. Ethnobotanical Uses: The plant has been used medicinally and ceremonially, and the seeds are also edible.

Broom GroundselSenecio spartioidesCharacteristics: Broom groundsel (or broom ragwort) is a perennial subshrub that grows from taproots forming woody crowns, with freely branching stems and narrow leaves. The yellow flowers, which consist of a compound center with radiating petals, grow in clusters of ten to twenty heads, and bloom from June to October. They are frequented by bees and other pollinators. Distribution and Ecology: Broom groundsel ranges from California to South Dakota and south to Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. This plant often grows in disturbed areas, on hillsides, and along stream banks from 3500 to 11000 feet. Ethnobotanical Uses: Groups indigenous to the San Juan Basin most commonly used parts of the plant for medicinal purposes, although they would also make the seeds into porridge and cakes during times of famine.

GlobemallowSphaeralcea coccineaCharacteristics: Distantly related to the marshmallow plant, globemallow produces upright stems but also sprawls as it grows, producing densely-clustered, hairy leaves and globular orange-red flowers. The flowers attract many pollinators and are especially important for bees; one can often see the flowers teeming with insect life when they are in bloom. Distribution and Ecology: Globemallow is found in a variety of environments, ranging from Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada south to Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Ethnobotanical Uses: Seeds and flower parts from globemallow have been found at many archeological sites in the Four Corners region. While the fruits and seeds can be eaten, the plant has most prominently been used for medicine and ceremonies.

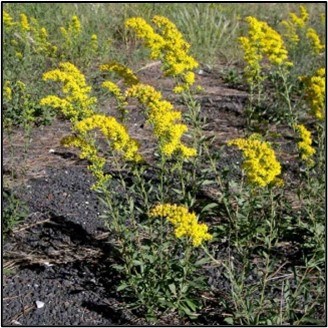

GoldenrodSolidago canadensisCharacteristics: This distinctive plant has small radiate yellow flowers; often, they grow on one side of the many spreading, reoccuring branches full of long, lanceolate leaves. Goldenrod flowers from July to October, and it is closely related to daisies and sunflowers. The common name is used to describe a variety of species in the genus Solidago; the one listed in this guide is the species that is normally found in the Four Corners region. Distribution and Ecology: Goldenrod is widespread, being found in eastern North America from Newfoundland to Virginia and west to Montana, Nevada, and Arizona. It is found at elevations from 2500 to 8500 feet. Ethnobotanical Uses: The indigenous uses of goldenrod have varied greatly between different groups of people, and in some cases these uses are also heavily influenced by which species grows in the climate of a given area. The leaves and seeds were eaten, and the roots were steeped in order to be eaten or, sometimes, smoked along with tobacco. The bright yellow flowers of Goldenrod have been used to create yellow and gold dyes for wool, cotton, and basketry.

Prairie ConeflowerRatibida columniferaCharacteristics: Prairie coneflower is a perennial herb, and when flowering (usually between March and November) it can easily be distinguished by its columnar flower head. The petals at the base of the flower head may be red, yellow, or a mix of the two. The plant tolerates drought, and attracts bees along with other pollinators. Distribution and Ecology: This plant grows over much of the Great Plains at elevations of 4000 to 7500 feet, stretching from south-central Canada to north Mexico; it can be found as far west as Idaho and as far east ast Minnesota. Coneflower can be found in both piñón-juniper and ponderosa woodlands, often in and around clearings, as well as in prairies and grasslands. In addition, it often grows in areas that have been cleared or otherwise disturbed by humans. Ethnobotanical Uses: Prairie coneflower has had a variety of ceremonial and medicinal uses amongst the indigenous peoples of the Four Corners, among them relieving stomachaches, headaches, and fever.

Prince's PlumeStanleya pinnataCharacteristics: Between April and September, Prince's Plume produces a prominent stalk of yellow flowers, with silvery, narrow leaves growing below. The hardy flowers can last for weeks or even months and attract pollinators including hummingbirds and a wide variety of insects. Distribution and Ecology: The presence of Prince's Plume indicates that the soil is rich in selenium, an element with similar properties to arsenic. Both selenium and arsenic form compounds that can be very toxic to humans. Prince's Plume occurs at altitudes lower than 9500 feet in many habitats, including chaparral, slopes, canyons, desert scrub, woodland, and sand dunes, as well as disturbed areas. Ethnobotanical Uses: Although Prince's Plume can be used as food or medicine, it must be properly treated to remove selenium compounds and other toxins. For example, in the Four Corners region, indigenous peoples boil the leaves multiple times in order to make them safe to eat.

Rocky Mountain BeeplantCleome serrulataCharacteristics: This is a plant that you will often see on roadsides throughout the Rocky Mountain area and much of western North America, for it thrives in areas that have recently been disturbed by humans, including construction sites and roadcuts. The name is appropriate, for the four-petaled, pink-purple flowers are an important source of food for bees and other pollinators, while the leaves are an essential food for the caterpillars of cabbage white butterflies (pictured below). The flowers bloom from May to August (concurrently with sunflowers) and produce long and slender dangling seed pods. The plant becomes especially abundant during late summer monsoons. Distribution and Ecology: In addition to disturbed areas, Rocky Mountain Beeplant thrives in open fields and forest clearings at elevations from 3000 to 9500 feet, provided there is plenty of water. It can be found throughout most of the states and provinces west of the great plains. Ethnobotanical Uses: Rocky Mountain Beeplant is, arguably, one of the most versatile plants in the Four Corners region, where for centuries indigenous groups have used it for food, medicine, and ceremonies. The seeds can be ground and made into mush, cakes, or bread (when mixed with wheat flour), while the young shoots can be eaten as fresh greens or preserved and stored for later use. The plant is also mixed into stews and parboiled to make delicious dumplings with either lard or meat. Outside of culinary uses, parts of the fermented plant can be made into a yellow-green wool dye, and some of the black-on-white ancestral Puebloan pottery that the Middle San Juan Basin is famous for uses an organic black paint, derived from the mature leaves.

Bob Moul, from Butterflies and Moths of North America

Threadleaf GroundselSenecio flaccidusCharacteristics: Threadleaf Groundsel is a good example of a plant that can be either toxic or a useful medicine depending on how much of it one consumes. Known for its showy, radiate yellow flowers that bloom through most of the year, the stems and leaves are covered in a dense coating of white hairs. Distribution and Ecology: Common and widespread throughout the southwest, this plant can be found at elevations from 2500 to 7500 feet, from California to Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas in the east and Mexico in the south. It may be growing on slopes and mesas and along washes. Ethnobotanical Uses: Multiple indigenous groups in the area have used this plant to make medicine, but only in very small doses, for large doses are toxic to humans. Threadleaf groundsel has also been used in ceremonies as well as to make brooms and brushes, including one version used to dislodge and remove spines from prickly pear cactus fruit.

Wild Four o'ClockMirabilis multifloraCharacteristics: This incredibly distinctive sprawling, perennial herb has large, showy magenta-purple flowers that protrude from papery flower cups and bloom in spring and summer. The leaves are large, fleshy, dark-green, and heart-shaped. Although it is not conspicuous, the plant grows a giant taproot that anchors it and obtains water from deep in the soil. Distribution and Ecology: Wild Four o'Clock is found throughout Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and northern Mexico at altitudes from 500 to 8500 feet. It does best in gravelly and sandy soils (as opposed to clay-rich soils), growing in creosote flats of the low desert, chaparral, and ponderosa forests. Ethnobotanical Uses: Evidence of prehistoric use of Mirabilis plants has been found at the ancient Fresnel Shelter site near the San Pedro mountains to the east, indicating that this plant has a long history of human use in the region. The taproot and other parts of the plant have been ground into medicine and used by the people of nearly all the modern Pueblos, with a variety of uses, including ceremonial use of the taproot. In addition, the flowers can be used to make dyes of purple and light brown shades.

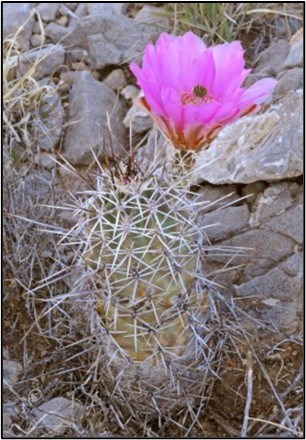

Succulents (Cacti and Yucca)Hedgehog CactusEchinocereus spp.

Characteristics: The genus Echinocereus contains the 60 or so species of hedgehog cactus. The stems of this genus are often under a foot in height and perhaps 2 to 3 inches in diameter. There is a wide variety of spines present, and sometimes they are so dense that the stem is not even visible. The flowers of this genus are some of the most brilliant in the cactus family (Cactaceae), ranging from electric pink to deep scarlet, to translucent brown and green and even to bright yellow.

Distribution and Ecology: Hedgehog cactus ranges from central Mexico north to the western United States. In the San Juan Basin, two common types are found: the Claret cup hedgehog (Echinocereus triglochidiatus, pictured below) and the Fendler's hedgehog (Echinocereus fendleri, pictured left). Both species are found growing along rocky outcrops, cliffs, and on sandy south-facing slopes, from 3500 to 9000 ft in elevation. You may notice hybridization of these two species on the native plant trail at Aztec Ruins. Ethnobotanical Uses: Hedgehog cacus fruits can be eaten fresh, baked like squash, pickled, or made into preserves, candy, and cakes. The pulp contains a lot of water, and so water can be extracted from it in emergency situations. Once dried, the waxy pulp can also be used to make candles.

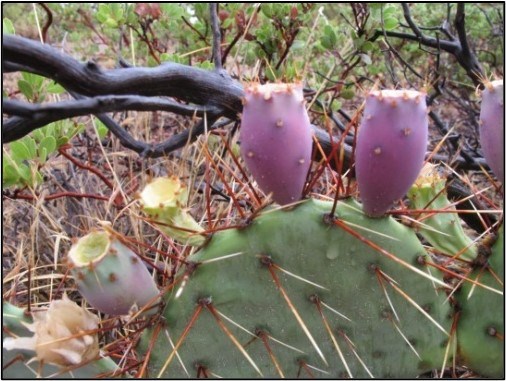

Prickly Pear CactusOpuntia spp.

Characteristics: Prickly pear cacti have distinctive fleshy, oval pads that grow on top of one another. Most have defensive spines that vary in size and grow out of the pads, which helps keep hungry herbivores like jackrabbits, deer, birds, squirrels, tortoises, peccaries, and beetles at bay. Opuntia has many species, and all of them are known for their beautiful flowers with numerous overlapping petals and showy stamens, which normally appear between May and July and attract bees and a wide variety of other pollinators.

Distribution and Ecology: Prickly pear cacti are widespread throughout western North America. There are several species present in the Four Corners area, and two can be found at Aztec Ruins National Monument: Brown spine prickly pear (Opuntia phaeacantha, left) and Plains prickly pear (Opuntia polyacantha, below). Both can be found in a variety of habitats ranging from 2000 to 8000 feet, producing yellow and peach-colored flowers. Ethnobotanical Uses: Prickly pear cacti have a long history of human use, with the ethnobotanical importance to ancient peoples being somewhat interchangeable among different species. In the Southwest and northern Mexico, the young pads (called nopales) are stripped of their spines, boiled, and eaten. Both the pads and the purple fruits, known as tunas, are excellent sources of dietary fiber and have been one of the most important sources of food in this region since ancient times. Aside from culinary uses, prickly pear cacti have been used to make medicine, glue, and dye. The spines can be used to make small arrow points and fishhooks, and the seeds can be made into beads.

Spinystar CactusEscobaria viviparaCharacteristics: The stems of this cactus are cylindrical and between 2 and 5 cm long and wide. The ribs are inconspicuous, and the spines are dense, white, and radial, with between 3 and 12 central spines. The lower central spine is reddish-brown and can be used to help distinguish this species, as can the stems, which are clumped or mounded and much darker than those of other cacti occurring in the mountains of western New Mexico. The flowers are pink, with the inner tepals being a light straw yellow. Little green fruits appear at the base of the plant after the flowers finish blooming. Distribution and Ecology: Spinystar cacus is found on sandy and rocky soils (especially limestone soils) in woodlands and forests from 4500 to 7500 feet, in western New Mexico and northeast Arizona. It prefers higher elevations than most other cacti found in this area, and is at risk for habitat loss due to climate change; it is considered rare in many Arizona counties and has protected status in that state. Ethnobotanical Uses: It is mentioned in the New Mexico Chapter plant directory that there is potential for the small green fruit to be eaten raw or boiled, but to what extent it was actually used this way has been poorly documented thus far.

Whipple's Cholla CactusCylindropuntia whippleiCharacteristics: Cholla cacti grow as small trees or shrubs, with long, slender branches. Whipple's Cholla is the only species in most of its range, and grows as a low-to-upright tree or shrub with sparingly to densely-branched whorled branchlets. The spines range from white to pale yellow to red-brown, and the flowers appear from May to July. Distribution and Ecology: Whipple's Cholla grows in northern Arizona and the Four Corners region, occurring in a wide variety of habitats from 4500 to 7000 feet, most with deep soils: valleys, plains, grasslands, woodlands, forests, and sagebrush. Ethnobotanical Uses: The fruits can be eaten raw, stewed and added to mush, or dried for use during the winter, while the buds can also be boiled. A number of groups in the Four Corners area have used the plant for medicine as well.

YuccaYucca spp.

Characteristics: The genus Yucca comprises about forty species of succulent plants in the agave subfamily. Most species of yucca lack a stem and instead have a rosette of stiff, sword-shaped leaves at the base, with clusters of waxy white flowers that appear from May to June.

Distribution and Ecology: On the Native Plant Trail (as well as along the Archaeological Trail) there are two species of yucca that commonly grow throughout the San Juan Basin: Narrow Leaf Yucca (Yucca angustissima, to the left) and Banana Yucca (Yucca baccata, above). These two species occur in desert flats and mesa, often in sandy habitats or sandstone outcrops, and can occur from 3000 to 7500 feet. In addition, in the West Ruin plaza along the trail to the Great Kiva, there is a large Soaptree Yucca (Yucca elata) that was planted during historic times; this species is considered non-native to this region, and is common further south in the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts. The pollination of yucca plants is unique, for they rely on the aptly named Yucca Moth (pictured below). Female moths visit yucca plants at night and crawl into the flower to lay a single egg in the flower's ovary. As she lays the egg, the female moth also deposits pollen in the flower, fertilizing the plant and allowing it to produce seeds. This is an example of a mutualistic relationship, where both parties benefit, since both the plant and moth rely on each other to reproduce. Ethnobotanical Uses: Since prehistoric times, yucca plants have been used in a wide variety of ways by the inhabitants of the Four Corners region, and their importance is underlined by their occasional representation in petroglyphs. The fibers of yucca are very commonly woven to serve a multitude of uses, such as sandals, rope, baskets, and mats; ancestral Puebloan examples of some of these uses can be seen in the Aztec Ruins visitor center. The leaves can be cooked in soups and boiled with meats, and the roots contain saponin, a substance that forms suds and allows yucca root to be used as a soap or hair shampoo. The roots have also often been used for medicine. Meanwhile, the fruits of both Banana and Narrow Leaf Yucca can be eaten raw, ground into meal and made into cakes, or dried and stored for long periods of time. In some cases, the seeds were removed from the roasted fruits and themselves mashed and made into cakes. The fruit is said to taste like summer squash, but the brown, outer layer of the fruits taste like dates.

Butterflies and Moths of North America

Ethnobotany Resource ListNative American Ethnobotany Database. University of Michigan – Dearborn. http://herb.umd.umich.edu/ Visit the database by scanning the QR code to the right.Brandt, Carol B. “Reading the ancestral Puebloan Landscape: a paleoethnobotanist’s text of seeds and wood.” Morrow, Baker. H and Price, V.B. Canyon Gardens: The Ancient Pueblo Landscapes of the American Southwest. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, c2006. Dunmire, W.W. and G.D. Tierney. 1995. Wild Plants of the Pueblo Province: Exploring Ancient and Enduring Uses. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press. Dunmire, W.W. and G. D. Tierney. 1997. Wild Plants and Native Peoples of the Four Corners. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press. Heil, K.D., S.L. O’Kane, Jr., L.M. Reeves, and A. Clifford. 2013. Flora of the Four Corners Region: Vascular Plants of the San Juan River Drainage Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. Rainey, Katherine D. and Adams, Karen R. “Plant Use by Native People of the American Southwest: Ethnographic Documentation’. Tull, D. 2013. Edible and useful plants of the southwest. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. General Reference ListBasinger, Ryan. “Food Plot Species Profile: Buckwheat” Quality Deer Management Association. January 14, 2015.“Cylindropuntia Whipplei” The American Southwest – Cacti. https://www.americansouthwest.net/plants/cacti/cylindropuntia-whipplei.html Edmunds, Daly and Nikonow, Hannah. “Celebrating Sagebrush: The Wests Most Important Native Plant.” Audubon. March 2018. https://www.audubon.org/news/celebrating-sagebrush-wests-most-important-native-plant Elpel, Thomas J. “Polygonaceae: Plants of the Buckwheat Family” Wildflowers-and-weeds. Copy right 1998-2019. “Escobaria vivipara.” SW Colorado Wildflowers. https://www.swcoloradowildflowers.com/Pink%20Enlarged%20Photo%20Pages/escobaria%20vivipara.htm “Escobaria vivipara” Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower center. https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=esvi2 Gauna, Forest Jay. “Plant of the Week: Prickly Pear” U.S Forest Service. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/opuntia_basilaris.shtml Gauna, Forest Jay, “Plant of the Week: Sagebrush.” U.S Forest Service. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/artemisia_tridentata.shtml Gauna, Forest Jay, “Plant of the Week: Spinystar” U.S Forest Service. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/escobaria_vivipara.shtml Kinsey, Beth. “Escobaria vivipara- Spinystar”. Southeastern Arizona Wildflowers and Plants. Firefly Forest. Copy right 2020. https://www.fireflyforest.com/flowers/1091/escobaria-vivipara-spinystar/ New World Encyclopedia Editors. “Buckwheat” New World Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, Inc. Shultz, Leila. “Pocket Guide to Sagebrush” PRBO Conservation Science. Copy right 2012. http://www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/SGI_Sagebrush_PocketGuide_Nov12.pdf The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Artemisia” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica,inc. April 01, 2010. https://www.britannica.com/plant/artemisia-plant The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica “Ephedra,” Enclycopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, inc. May 28, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Ephedra The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Prickly Pear” Encyclopedia Britannica. Enclycopedia Britannica, inc. August, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/plant/prickly-pear The Editors of Encylopedia Britannica. “Yucca: Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, inc. May 2019. https://www.britannica.com/plant/yucca |

Last updated: September 19, 2022