Last updated: August 30, 2017

Article

The Conspicuous Absence of the Wright Family at the U.S. outset of WWI

- written by Dayton Aviation Heritage NHP Historian, Edward Roach

Library of Congress / NPS

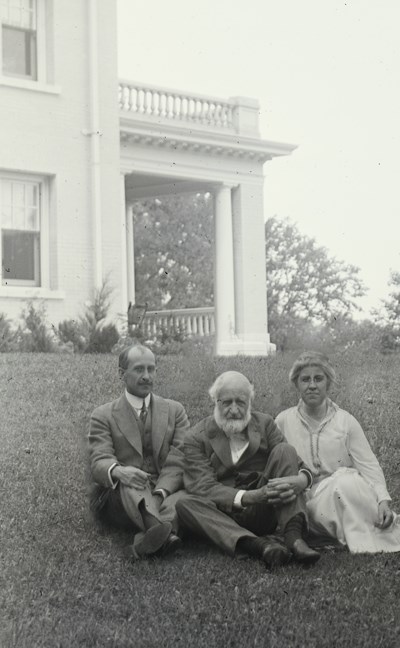

However, the declaration of war was not the issue most affecting the Wright household at Hawthorn Hill in early April of 1917. On the morning of 3 April, a Tuesday, Orville, Katharine, and Mr. and Mrs. Louis Lord, friends of Katharine’s from Oberlin, Ohio, awoke to find that Milton Wright was dead. The retired bishop of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ (Old Constitution) had died overnight, in his sleep in his bedroom on the second floor of the house. Milton, a diligent diarist, had kept up his written narrative until the end (writing on 2 April “Mr. and Mrs. Lord’s [sic] with us,” but he had not been well, having had a severe cold. Born in rural Indiana in the year that Andrew Jackson was first elected U.S. president, the 88-year-old Milton Wright lived through the Civil War, the end of slavery in the United States, Dayton’s growth as an industrial hub, and, of course, the invention of the practical airplane by his sons. Though active in the woman’s suffrage movement, he did not live to see the vote extended to women throughout the United States; that came only in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Milton’s funeral took place at Hawthorn Hill on the afternoon of 5 April, and he was buried in Dayton’s Woodland Cemetery beside his wife, Susan, who had died in 1889, and near his son Wilbur, who died in 1912. As the attention of much of the U.S. population turned to Europe and the military, the attention of the Wright family during that first week in April was decidedly domestic.