Last updated: January 9, 2025

Article

Women in the African American Civil Rights Movement: An Historic Context

Introduction

Throughout the history of the United States, Black women have participated across most major social movements. They found ways to organize and lead for a more just and equal society, not just for themselves, but for all people. When discussing Black women’s leadership and organizing efforts during the African American Civil Rights movement it becomes clear how often their contributions are overlooked. While countless women played important roles at various points during the Black Freedom Struggle, it is men who still receive more attention and credit for the successes of the movement, particularly in commemorative efforts and historical narratives. But the reality of the civil rights movement challenges these narratives. Many African American women operated as leaders at the local level, serving as the bridge between national and grassroots organizations. Their labor and sacrifice kept the movement going.

According to scholar Belinda Robnett, much of the labor of the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s was organized around gender. Men, particularly religious figures came to serve as formal leaders, which the movement then coalesced around at the national level. This meant that while Black women took on important strategic roles at the local level, they were often prevented from having a more visible role or accessing the highest levels of leadership in national organization. However, Black women’s activities must also be accounted for in order to tell a more accurate and comprehensive history of the movement.

Mainstream histories of the civil rights movement tend to praise a certain type of Black womanhood. Women such as Rosa Parks, are reduced to limited images of obedient femininity, or “accidental” matriarchs. This phenomenon of rendering Black women civil rights activists as two-dimensional steals their agency, and reproduces what historian Jeanne Theoharris terms “gendered silences,’ within the larger history of the movement. It also implies that Black women’s activism should be passive and unassuming. This only works to further obscure the overt misogyny Black women faced both within and outside of the movement as they tried to advocate for their interests and safety. These women were organizers and leaders in their own right, but efforts to memorialize them neuters their politics, marginalizing their work and placing them in the shadows of the men who have come to dominate popular narratives. Coretta Scott King, like Rosa Parks has seen her activism erased and reduced to being Dr. King’s wife and widow. However, her activism began before her marriage to King and extended beyond his death. Throughout her life she also voiced her experience with sexism and inequality with the Black freedom struggle:

Not enough attention has been focused on the roles played by women in the struggle. By and large, men have formed the leadership in the civil rights struggle but there have been many women in leading roles and many women in the background. Women have been the backbone of the whole civil rights movement…Women have been the ones who have made it possible for the movement to be a mass movement…

Rethinking how we frame Black women’s activism during the African American Civil Rights movement necessitates interrogating the narratives that have taken hold in popular memory. The movement is more than Great Race Men, and the women who led, organized, challenged, and endured, deserve to have their experiences moved from the periphery of the movement’s history to its center. It is from there where we can begin to understand how crucial Black women were and are to ongoing struggles for liberation.

Historical Overview

Prior to the modern African American Civil Rights movement, Black women were already active participants in the struggle for social justice in the United States. Organizing through churches and eventually through the creation of Black women’s clubs, a movement which began in earnest toward the end of the nineteenth century, there is a tradition of service and sacrifice that is foundational to Black women's continued organizing efforts. The creation of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, the National Council for Negro Women, and other similar organizations help to lay the foundation for women’s leadership during the modern Civil Rights Movement.

The Civil Rights Movement cultivated a culture in which participants, particularly women, began to question and challenge societal norms. For Black women who grew up in the church, participating in the movement transformed their understanding of their role in the community.

You have to understand that I grew up in a church, and the women sat on one side in the Amen Corner and the men sat on the other side in the Amen Corner. The pulpit was in the center, and the only time the women went up was on Women’s Day. Now, the civil rights movement was the one time I saw women going up into the pulpit because they were leaders of the civil rights movement...I say the leadership structure changed...The woman was the most powerful person in the local community...

While the Black church could be a place where Black women expressed their leadership qualities and exerted occasional influence, ultimately Black men led these religious institutions and were the primary decision-makers. So, while some women participants began to more openly challenge male dominance in the movement, they were still kept from holding leadership positions in organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The women leaders of the African American Civil Rights movement however, did not let these types of slights stop them from continuing to do the necessary and important work.

Scholar Janet Dewart Bell cites three modes of Black women leadership during the Civil Rights Movement: transformational leadership, servant leadership, and adaptive leadership. Eschewing leadership from the top-down, transformational leaders such as Ella Baker, encouraged people to develop their own approaches and supported them emotionally, materially, and logistically to achieve their goals. Transformational leaders motivate and inspire others by being reliable, transparent, and inclusive, thus bringing more participants into the fold. Servant leaders have little interest in gaining powers for themselves and instead “embrace work without recognition,” however they knew when to utilize strategy recognition in order to help foster the work and galvanize participation in the movement. An example of this is Jo Ann Robinson, Alabama educator and leader of the Women’s Political Council in Montgomery. Robinson organized the bus boycott and handled day to day operations, while allowing men like E.D. Dixon and emerging leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr to be the public facing leaders of the Montgomery Improvement Association. Finally, adaptive leadership is most concerned with ensuring that leaders can thrive and receive the support necessary to continue the arduous work of social and political organizing. Like their male counterparts, Black women faced threats of violence. The social support networks they created allowed them to adapt and persevere.

All of the figures highlighted in this document exhibit at least one of the types of leadership models described by Bell. Each woman and her experiences with gender and race discrimination shaped how she responded to external pressures and navigated her role in the movement. Exploring this allows us to better understand how Black women willing put themselves in the line of fire to become the architects of a cultural shift that sought to rid the nation of the vestiges of slavery and its afterlives, not for personal gain, but for the future of their communities.

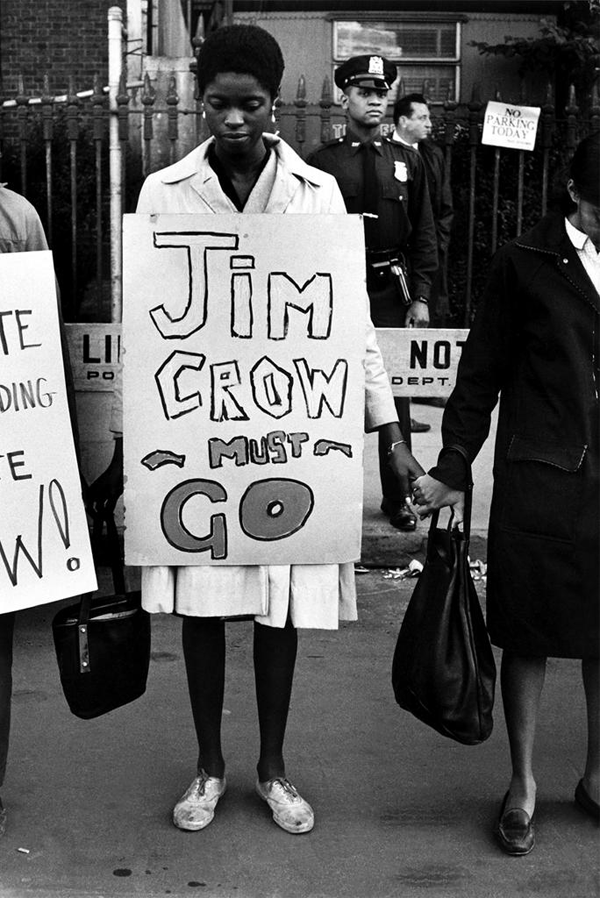

Fair Use Image

Key Figures

Dorothy I. Height (1912-2010)

Born in Richmond, Virginia on March 24, 1912, Dorothy Irene Height committed her life to racial justice and gender equality. In high school, Height became politically active in social movements, participating in anti-lynching campaigns. She also showed great talent as an orator. Her skills as a speaker took her all the way to a national oratory competition. She won the event and was awarded a coveted college scholarship.

Height had applied to and been accepted to Barnard College in New York, but as the start of school neared, the college changed its mind and refused to admit her, telling Height that they had met their quota for Black female students. Undeterred, she applied to New York University, where she would earn two degrees in four years: a bachelor's degree in education in 1930, and a master's degree in psychology in 1932.

In 1937, as a caseworker for the Welfare Department in New York City she connected with Mary McLeod Bethune, founder of the National Council for Negro Women (NCNW), Bethune served as Height’s mentor until her passing in 1955. Two years later Height ascended to the presidency of the NCNW, a position she held from 1957-1998. A member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority as well, Height served as the organization’s national president from 1946-1957 when she assumed her role with the NCNW.

During the tumult of the late 1950s through the 1960s, Height led the NCNW. One of her crowning achievements was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963, which she helped organize. She had strong working relationships with nearly every major civil rights leader including A. Philip Randolph, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Ella Baker, and Roy Wilkins. Height later wrote that the March on Washington event had been an eye-opening experience for her. Although she stood close to King when he delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech, and despite her skills as a speaker and a leader, Height was not given the opportunity to talk that day. Her male counterparts "were happy to include women in the human family, but there was no question as to who headed the household," she said.

Height was also involved in a number of other prominent organizations, notably the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA). She served as their National Interracial Education Secretary in the 1940s and in 1955 became the first director of its Center of Racial Justice. In 1971, Height helped found the National Women's Political Caucus with feminist icons Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, as well as Congresswoman Shirley Chisolm. Height received many honors for her contributions to society and in 1994, President Bill Clinton awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Highlander Research and Education Center via the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities

Septima Poinsette Clark (1898-1987)

Born in 1898, Clark was the daughter of a formerly enslaved father and a free-born mother. She was born and raised in Charleston, South Carolina. After graduating from the Avery Normal Institute in 1916, Clark began her career as a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse. Clark, like other Black educators, was limited in where she could and could not teach. African Americans were not allowed to teach in the Charleston public school system, and instead had to teach in rural, underfunded schools. After Clark joined the Charleston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), she began to get more involved in social justice issues. Clark and other schoolteachers created a campaign to protest the discrimination they faced. Their campaign was successful, and they gained the right to teach at public schools in Charleston.

Clark and the NAACP didn’t just stop there. In the 1950s they advocated for the integration of the public school system. Clark’s membership in the NAACP could cost her her teaching position and she was cautioned to keep it a secret. She refused. As a result, the school board fired her. This was not the crushing blow the board thought it would be. Instead, Clark, now no longer employed, devoted all of her time to activism. She designed educational programs to teach African American community members how to read and write. Clark, along with Bernice Robinson, a fellow educator and organizer, served as coordinators of Citizenship Schools. These schools, based on the model of the Highlander Citizenship School in Tennessee, provided instruction primarily in the areas of adult literacy and voter registration, but also covered political parties, local school boards, taxes, and social security. Clark’s teaching practice successfully bridged the divide between individuals and the national movement by connecting people’s everyday struggles under racism to the larger issues of structural inequality and discrimination. These schools, located throughout the South, were also attended by activists like Rosa Parks and Diane Nash and helped mold people into leaders in their own right.

Clark was a pioneer in grassroots citizenship education. For her continued work in the movement, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) made her Director of Education and Teaching when they acquired the Highlander School's Citizenship Education Program (CEP) after the state of Tennessee forced the school to close. Clark found that the men in power at SCLC “didn’t respect women too much.” Her ability to weather racism on one front, and sexism in her own community on another front, speaks to the double jeopardy of Black women’s oppression. Her struggles are not unique, and other civil rights figure such as Ella Baker knew this experience all too well.

Shaw University

Ella Baker (1903-1986)

Ella Josephine Baker was tireless in her pursuit of justice. From the 1930s on, Baker participated in over 30 organizations and campaigns, though her most documented and lasting impact stems from her role in the modern African American Civil Rights Movement. Baker was born on December 13, 1903 in Norfolk, Virginia. After completing grammar school, she enrolled in Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina where she graduated at the top of her class in June 1927.

After graduation Baker moved to New York City, where she became a waitress and a community organizer involved in radical politics. Within the year she began working as a journalist for the American West Indian News and by 1930, she was named office manager of the Negro National News. Along with her journalism career, Baker continued her political work. With African American socialist George Schuyler, she cofounded the Young Negroes Cooperative League (YNCL). She served as the organization’s first secretary-treasurer, and chairman of the New York Council. In 1931, Baker became the YNCL’s national director. Her successful tenure with the organization led Schuyler, the organization’s president, to recommend her to the NAACP.

By the late 1940s Baker, in her capacity as a field secretary, was the NAACP’s most effective organizer as she traveled the South chartering new branches. She later served as executive secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and most notably founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), serving as an advisor and mentor to the young activists in the grassroots organization. Individuals like Diane Nash, John Lewis, and Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) revered her as their “political mother.” In a career spanning more than five decades, Baker became the most influential woman in the modern Civil Rights Movement. Her approach rejected the messianic, charismatic leadership style of the period, instead arguing for a collectivist, participatory democratic approach that emphasized leadership from the bottom up. Baker’s modeling of a militant, antiracist political philosophy that subverted traditional class and gender structures would have a lasting effect well into the Black Power phase of the movement.

What makes Ella Baker such a powerful figure is that she challenges the prevalent stereotype that Black southerners were complacent and passive to Jim Crow before the modern iteration of the Civil Rights Movement. Baker’s defiance of this and other stereotypes which dominate the discourse make her compelling as an historical figure. Her life and work demonstrate that Black women in particular were the vanguard of the movement, even when working from behind the scenes.

New York Public Library

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977)

Fannie Lou Hamer, born Fannie Lou Townsend, was a Mississippi sharecropper who emerged as a transformational grassroots leader. Born to a family of sharecroppers on October 6, 1917 in Montgomery County, Mississippi, she was the youngest of twenty children. She rose to national prominence in 1964 during Freedom Summer, a nonviolent campaign to end segregation in Mississippi through mass voter registration efforts.

Hamer co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) that summer. The Democratic party in Mississippi barred Black participation, threatening to withhold support for the national Democratic ticket. Hamer, along with other MFDP leaders, traveled to Atlantic City, New Jersey to attend the Democratic National Convention and argue that they should be the official delegation to represent the state of Mississippi. Her testimony about the oppressive conditions under which Black Mississippians lived their daily lives was carried on television stations across the country, even though President Lyndon B. Johnson delivered an” emergency” press conference to prevent Hamer’s testimony from going live on the three major television networks at that time. Hamer continued to campaign for voting rights in Mississippi. In both 1964 and 1965 she ran for Congress unsuccessfully. In 1968, she was part of the Mississippi delegation to that year’s Democratic National Convention where she protested the Vietnam War.

Conclusion

Black women have played significant roles in the ongoing struggle for liberation and freedom in the United States. From the abolition movement of the 19th century to the civil rights movements of the 20th century and continued calls for justice in the 21st century, women have played important and central roles, many times with little recognition in comparison to their male counterparts. Women frequently played an important role in the modern African American Civil Rights movement; however, their efforts were often downplayed or overshadowed. Mainstream narratives and popular histories of the movement continue to highlight figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or other Great Man figures to the detriment of the work and sacrifice Black women frequently made as bridge leaders, scholars, and organizers. Contemporary commemorations highlight women such as Ella Baker and Rosa Parks, but reduce their contributions to fit a more neat and digestible narrative. Today historians, educators, and scholars who study Black women’s history work to subvert stereotypes and misinformation helping to move the women of the African American Civil Rights Movement from the periphery of historical narratives to front and center where they belong.