Heather Munro Prescott is professor of history at Central Connecticut State University. Her research and teaching interests include US women’s history, history of medicine and public health, and the history of childhood and youth. Her first book, A Doctor of Their Own: The History of Adolescent Medicine (Harvard, 1998), received the Will Solimene Award of Excellence in Medical Communication from the New England Chapter, American Medical Writers Association. Her most recent book is The Morning After: A History of Emergency Contraception in the United States (Rutgers, 2011).

Bibliography

Anzalone Christopher A., ed. Supreme Court Cases on Gender and Sexual Equality. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Berenson, Barbara F. Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement: Revolutionary Reformers. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2018.

Clifford, Deborah P. “The Drive for Women’s Municipal Suffrage in Vermont, 1883–1917.” Vermont History 47, no. 3 (Summer 1979): 173–190.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848–1869. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978.

Flexner, Eleanor. Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States. 1959. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

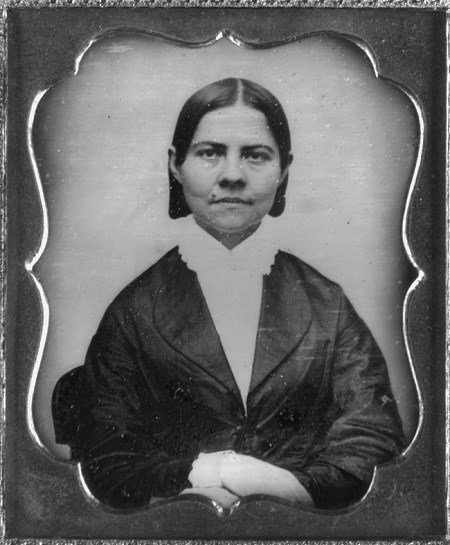

Kerr, Andrea Moore. Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

Nichols, Carole. Votes and More for Women: Suffrage and After in Connecticut. New York: Haworth Press, Inc., 1983.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920.

Tetrault, Lisa. The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Thomas, Edmond B. Jr. “School Suffrage and the Campaign for Women’s Suffrage in Massachusetts, 1879–1920.” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 25, no. 1 (Winter 1997): 1–17.