Last updated: October 24, 2018

Article

Training for Trench Warfare

When the Great War began, fighting between Central and Allied powers quickly turned into a stalemate along the Western Front. With troops embroiled in defensive trench systems that extended from the English Channel to Switzerland, attempts to achieve a breakthrough resulted in tremendous casualties with few appreciable gains. In more than two years, the lines of battle moved less than ten miles. By the time the United States entered World War I, European powers had advanced the craft of trench warfare, developing a new subterranean level of entrenchment.

The Bayonet, 1917.

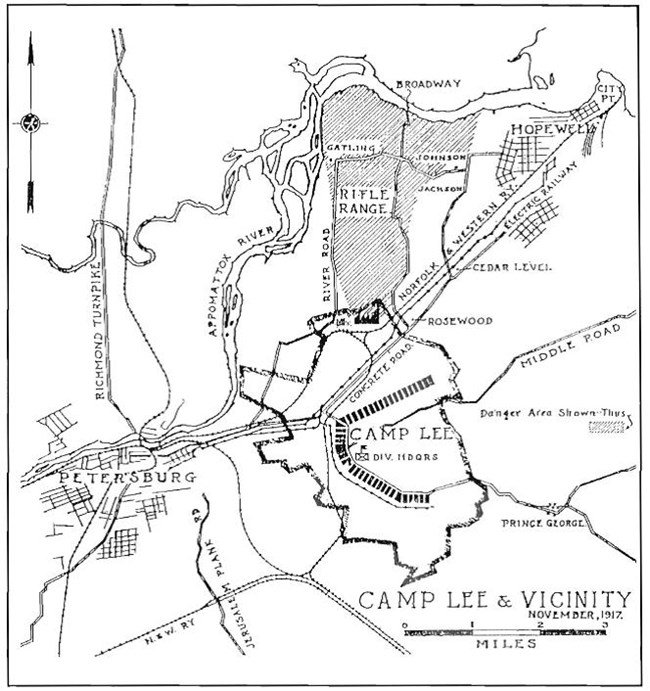

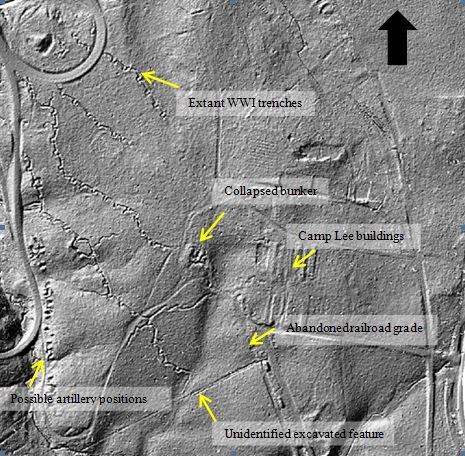

In June, Camp Lee, named in honor of Robert E. Lee, was established near the battlefields of Petersburg where evidence of the siege still marred the earth. For two months, 14,500 workers rapidly cleared trees, drained wetlands, built roads, installed water and sewer systems, and constructed buildings to accommodate over 60,000 soldiers. The cantonments were all designed using standardized building plans from the War Department, though the final layout was dictated by topography. They contained few luxuries, but the coming war brought new railroads, electricity, and piped water. Camp Lee would ultimately cover 5,542 acres, contain 1,532 buildings, and mobilize over 138,000 troops – more than any other Army installation during the war.

U.S. Army Quartermaster Museum

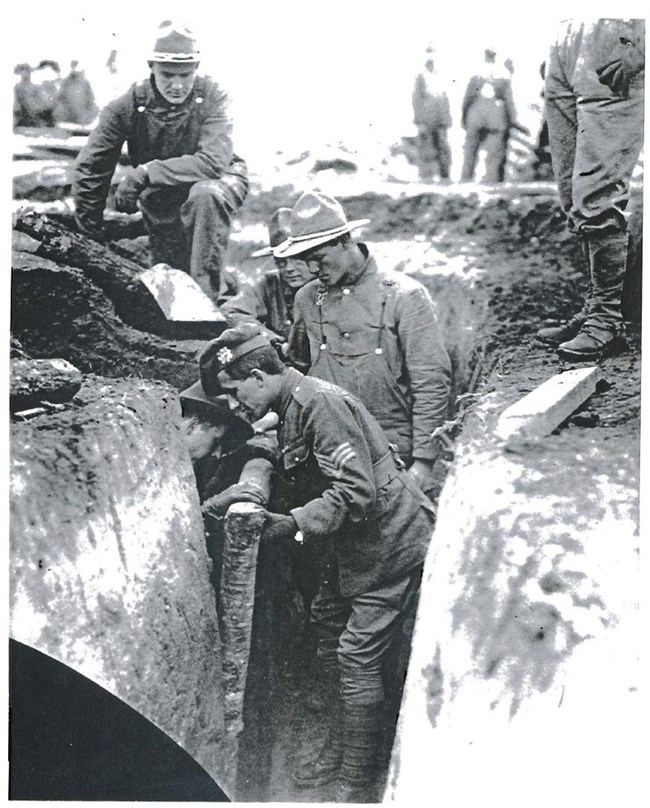

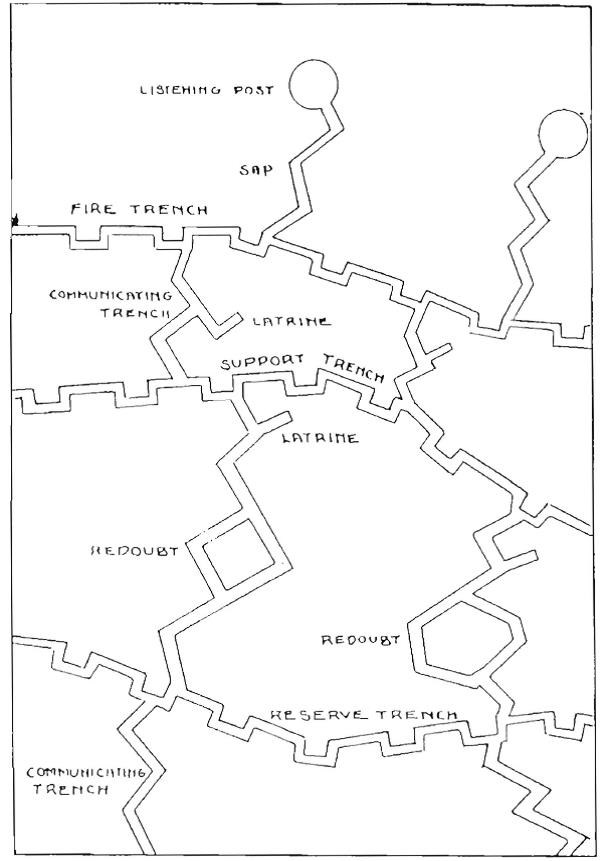

Due to these less than ideal circumstances, the War Department created guidance which outlined a 16-week course on the scope of training necessary to provide new divisions with instruction on trench warfare. The booklet directed commanders to construct trench systems within each cantonment area, reiterating that “Instruction in trench warfare cannot be properly developed without a trench system. It will be one of the first duties of a division commander [...].” The Department further issued a directive of notes compiled by the British General Staff which contained detailed information about the construction and use of trenches.

National Archives and Records Administration, RG 77

By November, foreign military instructors began to arrive from Great Britain, Scotland, and France to oversee the training program, bringing with them the horrors of World War I. This advanced instruction included trench construction, rifle marksmanship, bayonet courses, grenade practice, gas defenses, marches, and basic drill. The sub-zero conditions compelled the Army to move much of the training indoors however, instead subjecting the new troops to long lectures. The soldiers, with their poorly insulated barracks and incomplete uniforms, felt the extraordinary cold nonetheless.

Mike Brock Collection

Throughout the winter, soldiers single-mindedly constructed their trench systems in preparation for a live training exercise to be held in the spring. Spanning miles, the elaborate system included first line firing trenches, second line supporting trenches, third line reserve trenches, communications trenches, barbed wire entanglements, and other defensive features above and below the ground. In a time before mechanized heavy machinery was widely available, engineers and infantry required special instruction to safely and efficiently dig out bunkers up to 40 feet below ground. These shelters would serve as living quarters for dozens of soldiers during their training.

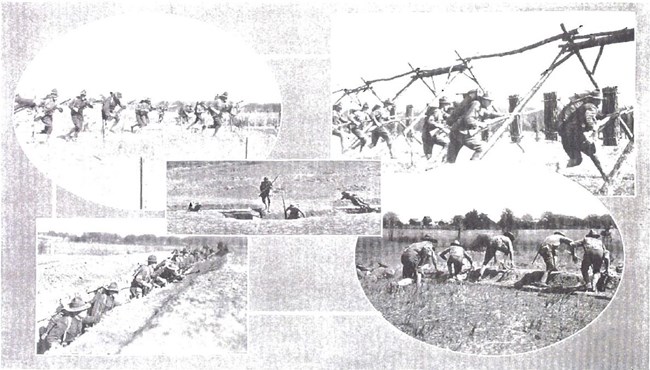

The scenario called for an attack from the east, indicating that trenches along the eastern side of the camp represent the front lines of the entrenched zone. Under simulated combat conditions, officers would lead the troops into the trenches, where they would live for days at a time learning to perform their jobs and how to be responsible for their shelter, food, and water. While officers orchestrated communications and artillery support, the troops would engage in raids against opposing enemy trenches.

Meanwhile, General John J. Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, was developing his own opinions based upon his observations in France. Pershing disagreed with the emphasis on trench warfare and believed that the key to victory lay in offensive maneuvers. He insisted that the War Department encourage training in “open warfare” instead. The result of these disagreements lead to a frequent shift in training priorities. Regardless, the troops would ultimately face the trenches upon arrival in Europe. Accordingly, the foreign instructors continued to emphasize it, despite Pershing’s demands.

However, when division commander Major General Adelbert Chronkhite returned from Europe convinced of Pershing’s insistence on open warfare, he greatly reduced the scale of the exercise, postponing it for warmer weather. Additionally, he further expanded the scope of training: “The officers and men will live in the trenches, but not for long periods. I can see no advantage in making men unnecessarily uncomfortable. […] And yet the value of training in trench warfare must not be lost sight.” And thus, in the last week of April, the training commenced.

The Bayonet

The Bayonet, Camp Lee’s newsletter, published accounts of the elaborate exercise, indicating that the trench system used for this training was in the center of the cantonment, using fictitious “Red” and “Blue” Armies embattled against each other, fighting to maintain their sector as well as practicing aerial camouflage. The 318th Infantry was the first to occupy the trenches. A reporter for the Richmond Times Dispatch described the scene:

“Seven machine guns were located at points of vantage. At some point back of the infantry, the artillery was located. Liaison officers of both artillery and infantry were with the men in the front lines. Telephone and visual communications were established. In the dugout of the battalion commander there was an improvised desk at which a soldier was writing on a typewriter. Only a weird lamp furnished light on both sides of the chamber. There were two bunks, for the major and his adjutant. On the desk was a telephone with a line established to all points of the sector.”

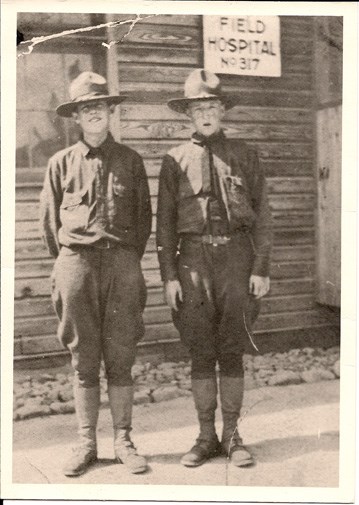

Each battalion spent only 12 – 24 hours engaged in the exercise, marching to the trenches, relieving the occupying battalion, and assuming a defensive position. The exercise included all of the supporting elements to a combat unit: medical and signal units established their positions to the rear of the front trenches, while the cooks prepared meals in field kitchens and delivered food to the soldiers in the trenches. Despite the limited scope of the exercise and brief occupation in the trenches, new recruits nonetheless were miserable and unprepared for the experience. Private Rush Young recalls,

“On April 30th we were ordered to the “Dummy” trenches in pouring rain for training in trench warfare. We were all willing to defend our country, but in these trenches we were getting thoroughly disgusted with army life. We had to move through these clay trenches for miles in mud and water up to our knees to get to the front line. Then in the front line we had to stand guard all night in the mud and rain in shifts of two hours each. There was sure some difference between the trenches in France and here. No comparison. Whatsoever. Although it rained most of the time in France, yet the trenches were fairly good in most places. It was a different kind of soil and in muddy places the trench and firing stand were laid with duck boards.”

Private Young, and likely others, felt that the similarities between actual warfare and the practice trenches was minimal. In May 1918, the full strength of the 80th Division, about 23,000 men, deployed to Flanders, France where they occupied a sector of British trench for several months before joining the American Expeditionary Force.

Vickers 1917

The elaborate, interconnected web of entrenched zones they found upon arrival was no match for modern artillery. On the eve of the American Civil War, D.H. Mahan had theorized that mechanized weaponry would forever change the face of war; his predictions would tragically be proven on the red fields and desperate, sucking trenches of World War I. The resulting mass casualties wreaked havoc on the battlefield terrain as much as the minds of those fighting.

Men and materiel were brought to the front via the communications lines, the highways of the trenches. At the forward edge, observation posts and machine gun emplacements separated the defensive zone from the “no man’s land” of barbed wire entanglements and a devastated landscape. Behind the entrenched zone, dugouts, called cave shelters or bomb proofs, dotted the landscape. Constructed of wood, steel, or concrete 25 feet below the surface, they were large enough for several hundred men, contained several rooms, at least two entrances and exits, and provided shelter for reserve troops, commands posts, and dressing stations during artillery barrages. These, along with the “creature comforts” of latrines, drainage holes, and minimalist shelters, completed the place they would call home until the end of the war.

Ed Elam Collection

On September 26, the final Allied offensive of World War I began, stretching along the entire Western Front. For nearly a month and a half, the Blue Ridge boys fought alongside over a million American soldiers in the largest, bloodiest offensive of the war: the Meuse-Argonne. As the only division to participate in all three phases of the offensive, the 80th earned a new motto and over 600 awards and citations for their actions during 48 days of combat. The “Strength of the Mountains” became “Only Moves Forward!”. Losses were exacerbated by the inexperience of many American troops, but what they lacked in training, they made up for in enthusiasm. Even suffering a 26% casualty rate, the 80th accomplished this feat with a smaller percentage of casualties than any other division engaged. On November 11, 1918, at the expense of more than 117,000 American lives, the war was finally over.

The following spring, the 80th returned home and was deactivated at Camp Lee on June 26, 1919. The system of trenches that survives is thought to be the largest and best preserved intact series of World War I trenches remaining in the country, much of which is found inside what is now Petersburg National Battlefield.

Regardless of era, the land is palpable with the bravery of patriotic Americans.