Written orders were delivered in envelopes that required a signature to be returned to headquarters as a receipt. However, when the envelope sent by Chilton intended for D.H. Hill wasn't returned, no alarm was raised at Lee's headquarters.

The Mysteries of the Orders

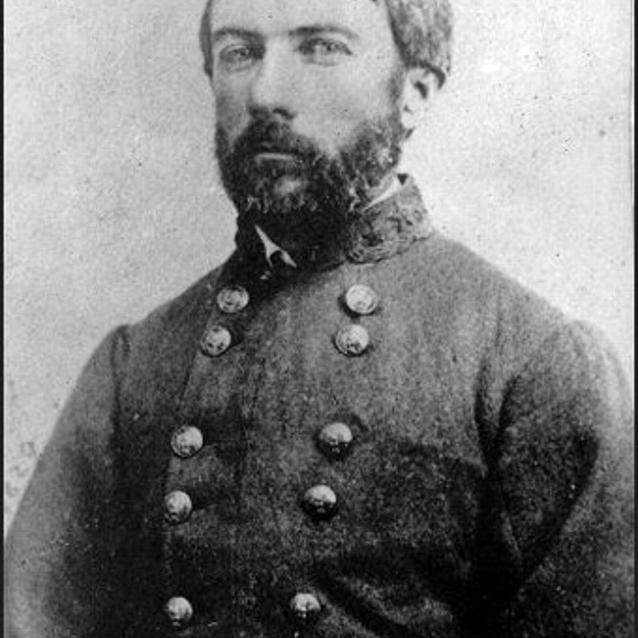

Library of Congress

D. H. Hill became the obvious scapegoat since his name was on the orders. In fact, several stories circulated about how Hill came to lose the orders. One suggested the orders were found on a table at a house which served as Hill's headquarters in Frederick. Another tells of Hill throwing the orders down on the street. These stories are complete hearsay and are prime examples of the misinformation perpetuated about the loss of the orders. In 1868, Hill wrote of the wartime editor of the Richmond Examiner who had blamed him for the loss, "The harsh epithets he applies to me are unworthy of the dignity of the historian, and prove a prejudiced state of mind. Second, if I petulantly threw down the orders (as was claimed), I deserve not merely to be cashiered, but to be shot to death with musketry. General Lee, who ought to have known the facts . . . never brought me to trial for it." In fact, when asked about Hill's guilt Lee said, he "... did not know that General Hill had himself lost the dispatch and in consequence he had no ground upon which to act, but that General Stuart and other officers in the army were very indigent about the matter." In Hill's defense, Major James W. Richford, his adjutant general, gave sworn testimony that it was part of his exclusive duty at the time to take custody of such papers, and no orders was delivered to him except the one from Jackson.

Hill spent many years after the war defending himself against accusations that he lost the orders, explaining that he went into Maryland under Jackson's command and was under his command when Special Orders 191 was issued. Therefore, he knew he would receive his copy of the orders through Jackson and not Lee. He also understood the sensitive nature of the orders and pinned it securely in his inside pocket. He was able to produce his copy of the orders from Jackson after the war to prove he had it. Walker did the same with his orders. Longstreet said he thought about pinning it in his jacket, but instead memorized, it then "chewed it up!"

Chilton's memory appears to have faltered in the matter; whether his was a case of selective memory or there were large cracks in administrative process due to the absence of Taylor and Marshall we may never know. In 1874, responding to former Confederate President Jefferson Davis' questions about the loss of the orders, Chilton said, "That omission to deliver in his (the courier's) case so important an orders w'd have been recollected as entailing the duty to advise its loss, to guard against its consequences, and to act as required . . . But I could not of course say positively that I had sent any particular courier to him (Hill) after such a lapse of time." In 1887 Chilton admitted to Hill he didn't have paperwork to prove the receipt had not been returned to headquarters, except to say that if orders were missing it should have been noticed.

Twenty-five years after the event, questions continued to circulate, but memories were fading. If Chilton discarded the orders realizing that Hill would receive his from Jackson, he never said so, nor did he remember which courier was sent to deliver the orders. Clearly, Chilton did not maintain proper administrative procedures in Taylor's absence. Hill and his adjutant remained adamant that the orders never entered their camp. Short of an admission of guilt squirreled away in an archive that has yet to be discovered, the guilty party may never be revealed.

Who Found the Orders?

Library of Congress

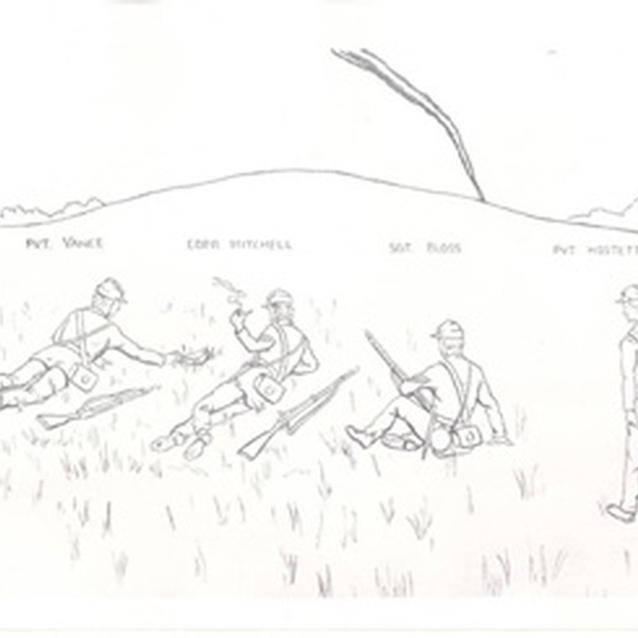

Among the many questions associated with the lost orders is the matter of who found it. Corporal Barton Warren Mitchell is most often attributed as the finder, and seemingly is the one who physically picked up the orders. There were several soldiers who were present when it was found, but when the story was retold through the years the finder changed numerous times.

After the war, Mitchell wrote letters to other participants in the campaign, including Bloss and Colgrove, and various government officials to gather necessary confirmation that he had been the one who found Special Orders 191, in order to petition Congress for recognition. Mitchell died in January of 1868, his son, William Mitchell, continued the task with letters to McClellan and Colgrove. Colgrove acknowledged that Mitchell was the finder of the orders, but Mitchell never received Federal recognition.

At the 27th Indiana Regimental Reunion in 1904, the issue of the lost orders was discussed among the surviving members Sergeant John McKnight Bloss and Private David B. Vance. Vance suggested that he picked up the package and gave it to Bloss while Mitchell merely picked up the cigars that fell out of the package. In 1905, Private Dariel Burrel, who was on the skirmish line with Company F said he saw the envelope laying in the grass and weeds and picked it up at the same time that Bloss asked him to hand it to him. It passed over Mitchell and the cigars fell out, but Mitchell did not see the papers. Private William H. Hosteiter, of Company A, said he was on the extreme left of his company, just to the right of Company F, and he saw, "Sergeant Bloss with the envelope in his hand drawing a paper or papers out of it, he then and there read the contents . . . " He claimed no one but Bloss handled the letter. Later, Bloss and Vance seemed to have come to an agreement that Bloss was the finder and Mitchell had a smaller role, and then in another script change, Vance claimed in 1904 that he was the finder of the orders.

Mitchell died in 1868 and could not defend his claim, but in the letter Bloss wrote thirteen days after the finding of the letter, he gave Mitchell credit for finding it.

Corporal Mitchell was very fortunate at Frederick. He found General Lee's plan of attack on Md and what each division of his army was to do. I was with him when he found it and read it first. I seen its importance and took it to the Col. He immediately took it to General Gordon, he said it was worth a Mint of Money & sent it to General McClellan.

In different accounts, various individuals were given credit for finding the orders; however, the simple answer is that Mitchell and several other soldiers on the skirmish line were probably all involved.

Part of a series of articles titled The Lost Orders.

Previous: Confederate Plans

Next: Special Orders 191 Today

Last updated: February 3, 2015