Part of a series of articles titled Invasive Species in South Florida.

Article

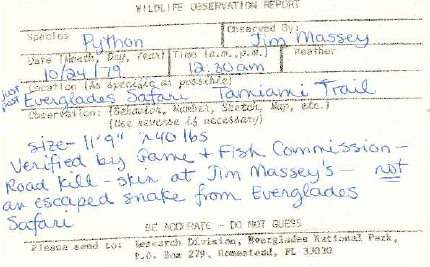

The First Recorded Python in Everglades National Park, 40 Years Later

NPS Photo

Everglades National Park just had a 40th anniversary on October 24. It’s one anniversary we’d rather not celebrate. That’s the day in 1979 when the first recorded python was caught in the park near Everglades Safari Park on Tamiami Trail.

Although the actual species is not listed on the record, researchers presume that this report was of a Burmese python, the invasive snake that has been linked to the severe decline of mammals in the park. And many also think that this was not the first Burmese python in the park.

“There have been observations of large snakes from Asia for over 100 years in Florida, but this 1979 date is the first recorded removal from the Everglades,” said Bryan Falk, supervisory invasive species biologist for Everglades National Park. “Historical reports like this help us piece together the past and paint a picture of how and when these pythons became established in the park.”

Forty years after that first report, we still have a lot to learn about pythons in the Everglades and how to control their spread. That’s not due to lack of effort.

NPS photo

Tools in the toolbox for python control

Park and partner scientists have tested many methods to slow the spread of these invasive snakes. Everything from visual surveys, to training dogs to locate the snakes, to trapping, to pheromones, and more, have been tried.Each tool is successful to some extent, but there isn’t yet one method that can remove all Burmese pythons from the Everglades. So, it’s best to use multiple tools at the same time.

Expert snake searchers have removed thousands of pythons from the Everglades in the last few years, but almost all these removals occur only on roads because the pythons are so cryptic that they can’t be seen otherwise.

Trained dogs can sniff out an area where a python may be hiding, but pinpointing exactly where the snake is located is still difficult.

Trapping is possible, but food-baited traps aren’t extremely successful when food is plentiful or with sit-and-wait predators, like pythons, that wait for their food to come to them.

Removing large, reproductive females may help slow Burmese python population growth, and that’s the focus of what’s been nicknamed a “Judas snake” approach.

Large male pythons are caught, implanted with radio transmitters, and released back where they were captured. Biologists use the radio transmitters to regularly find the snake. Because multiple male pythons may find and court female pythons during the mating season, these “Judas snakes” lead researchers to other pythons, including large females, before they have the chance to produce more pythons.

Results are promising, and several large reproductive females have been recently caught using this method. And scientists are trying to make this method work even better.

A major downfall of using Judas snakes is that female pythons aren’t receptive to mating for very long, making it less effective. The US. Geological Survey, in partnership with the National Park Service and university researchers, is working to fix this by implanting the radio-tagged male snakes with female hormones.

Researchers expect that these “feminized” male snakes will exhibit female pheromones that attract other males. They also expect the pheromones to work for a much longer period of time. This should increase the chance of finding Burmese python mating aggregations, and thus facilitate removal of even more pythons.

Will Judas snakes and pheromone research facilitate the removal of all Burmese pythons from the Everglades? Most likely not. But it’s another tool to manage their spread and control their populations.

Why are invasive species so hard to get rid of?

The more I learn about invasive species, the more I think of them as a cancer in our environment. Like cancer cells, once they become established, they’re hard to completely remove.

The quicker you catch them, the easier they are to eradicate. And often the best way to eradicate them is by using a combination of methods. You have to throw all the tools in your toolbox at the problem.

Even if you have a successful eradication, you’ll always have to do routine checks and maintenance to ensure they are gone.

So like cancer, invasive species are hard to remove, difficult to deal with, and they can really get you down.

But the park is not going to give up in the fight.

“This is a big deal for all of us here in Everglades National Park,” said Pedro Ramos, superintendent of Everglades and Dry Tortugas National Parks. “What concerns me most as a park manager is the invasion of plants and animals that seem to be taking over the landscape, both on land and water.”

Ramos knows we don’t have a silver bullet for the invasive species problem, but he has some ideas for how to move forward.

“There are two things we can do,” Ramos said. “One of them is to continue our efforts. We cannot throw in the towel. The other thing is to invest in research because we all know that’s where the answers are going to come from.”

Python lessons in Everglades National Park: Never let it happen again

Forty years later, Burmese pythons are now distributed throughout southern Florida. State and federal land management agencies, including the National Park Service, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the South Florida Water Management District, are partnering to support and further develop methods that will help with the Burmese python problem.

But, ultimately, that first python record will serve as a reminder of how vulnerable the southern Florida ecosystem is to invasive species and how hard it is to get rid of them once they are here. We have to do our best to make sure this doesn’t happen again.

So while pythons are a major problem in the park, there are many other invaders that also need attention. That’s why park biologists are focused on removing new species before they become established while also managing the ones that we already have.

Argentine black-and-white tegus, for example, are knocking on the park’s door, and park biologists continue to add more traps around the park’s boundary and expand the area where they trap these large lizards. The goal is to keep a breeding population from becoming established in the park. So far, so good.

But it’s going to be a tough battle to fight. Over 500 tegus were caught this year just outside the park, which is a 66 percent increase over last year. Several were caught inside the park, but researchers don’t yet think there is a breeding population there and want to keep it that way.

African red-headed agama lizards—now common in Homestead and other areas of southern Florida—were first removed from the park in early 2019. Since then, park biologists are routinely checking for and removing them from wherever they have been sighted.

Japanese climbing fern was spotted and removed from the parking lot at the Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center headquarters in 2017. This invasive plant can easily outcompete native plants.

NPS Image

Invasive Species – What Can We Do?

The single most effective way to not have invasive species in Florida is by not letting them get here in the first place. Don’t let it loose. If you have an exotic pet you no longer can care for, please never, never release it into the wild.

One way you can ensure your exotic pet gets a good home is through Florida Fish and Wildlife’s Exotic Pet Amnesty Program.

But if an exotic species is released, early detection is our next best bet to prevent a new population from becoming established.

If you see any animal or plant that is unusual, please report it to IveGot1, either on the web (IveGot1.org), on the IveGot1app, or by calling 1-888-IVE-GOT1. This will notify the network of South Florida invasive species scientists.

“Reports from the public are incredibly important because they help us make management decisions,” Bryan Falk said. “The first report of an invasive species can help us remove it before it becomes established. But even repeat reports can provide a lot of information. If we’re getting reports of the same invasive species on Tamiami Trail, the main park road, and in East Everglades, we know the population is probably widespread and we should respond accordingly.”

If you remember anything about invasive species, remember these two facts:

-

Don’t let it loose! Please never let your pet out into the wild.

-

Report any invasive species to IveGot1, either on the web (IveGot1.org), on the IveGot1app, or by calling 1-888-IVE-GOT1.

Last updated: October 25, 2019