We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree. Frederick Douglass

Architect of the Capitol

Rarely in history has the link between the blood shed on the battlefield and the freedom of millions been as clear as it was September, 1862. At the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, over 23,000 men fell as casualties in a single day of battle - more than the total casualties of all America's previous wars combined. Just five days later, on September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. This declaration was the result of a long struggle, dating back to the very foundation of the country. From the moment that Thomas Jefferson penned those immortal words, "all men are created equal," a great national debate spread through the nation, attempting to define citizenship, personhood, and freedom. In 1861, that debate had descended into civil war.

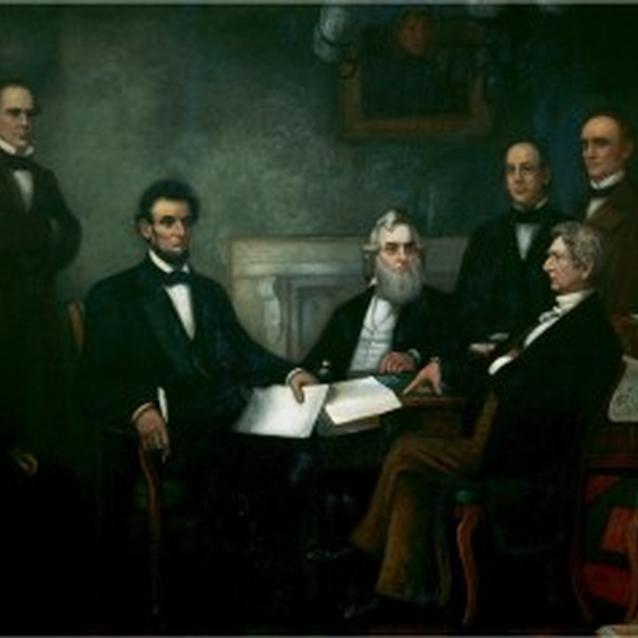

By the summer of 1862, with casualties mounting across the country, Lincoln realized it was time to embrace a higher goal for the conflict. On July 22, he introduced to his cabinet a proclamation declaring that all slaves in states in active rebellion against the federal government would be freed under his powers as Commander-in-Chief. While nearly all of his cabinet members greeted the proclamation favorably, Secretary of State William Seward suggested Lincoln wait for a Union victory before issuing such an important policy. Seward believed putting forth such a revolutionary measure amidst Union setbacks on the fields of Virginia would take away much of the proclamation's power, giving it the appearance of an act of desperation rather than a bold move. Lincoln agreed. He held on to the document, waiting for a Union victory.

When Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River and began its invasion of Maryland, Lincoln made "a solemn vow" that should Lee be stopped, he would "crown the result by the declaration of freedom to the slaves." While the fate of the nation hung in the balance, and with the eyes of millions upon them, the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia clashed near the banks of Antietam Creek on September 17. Five days later, with Lee gone from Maryland, Lincoln had the victory he needed and he issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, stating that he would free all the slaves in any state "in rebellion against the United States" on January 1, 1863.

By the appointed deadline none of the Confederate states returned to the Union, so after standing in line for hours to greet the customary New Year's Day visitors at the White House, Abraham Lincoln retired to his office upstairs at the Executive Mansion and signed the final version of the Emancipation Proclamation. His hands were tired and trembling from shaking so many hands, and as he prepared to sign the document, he paused to let the quivering subside, and declared, as if to reinforce his resolve, "I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper...if my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it." Lincoln affixed a steady signature to the Emancipation Proclamation, competing what he would later call the great event of the nineteenth century."

The final proclamation, issued January 1, 1863, identified those areas "in rebellion." They included virtually the entire Confederacy, except areas controlled by the Union army. The document notably excluded the so-called border states of Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, where slavery existed side by side with Unionist sentiment. In areas where the U.S. government had authority, such as Maryland and much of Tennessee, slavery went untouched. In areas where slaves were declared free - most of the South - the federal government had no effective authority.

The Emancipation Proclamation had a profound influence on the course of the war and the institution of slavery. In addition to setting the state for the freedom of millions of former slaves, it was also a decisive war measure. It deprived the South of valuable slave labor for its war effort as thousands of slaves fled to nearby Union camps, and historians believe that it influenced the decision of England and France not to intervene on behalf of the Confederacy. It also allowed nearly 180,000 former slaves and free blacks to serve and fight alongside their countrymen as United States Colored Troops.

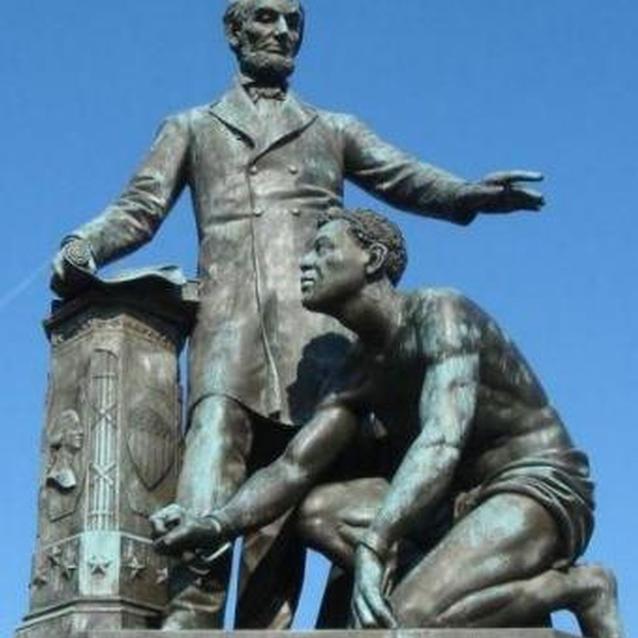

Although his famous proclamation did not immediately free a single slave, black Americans saw Lincoln as a savior. Official legal freedom for the slaves came in December 1865 with the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery.

Last updated: August 15, 2017