Last updated: November 19, 2022

Article

Monitoring Wetlands Ecological Integrity

NPS Photo

Background

Although wetlands comprise less than 10 percent of the land area in the Sierra Nevada, they provide numerous important functions. They are local and regional centers of biodiversity, and support species found nowhere else across western landscapes. Wetlands provide critical habitat for a variety of wildlife, play an important role in the life cycle of many invertebrate and amphibian species, and provide a wide variety of ecosystem services such as nutrient retention, flood control, and sediment storage. Wetlands are also valued aesthetic elements of Sierra Nevada landscapes and provide forage for wildlife and pack stock.The Wetlands Ecological Integrity monitoring project is designed to provide basic information on the condition of targeted wetlands and to allow for the evaluation of long-term trends in wetland plant communities, groundwater dynamics, and macroinvertebrates in Sierra Nevada national parks.

The wetland types targeted for monitoring are:

Fens: occur in basins, on slopes, or in association with distinct springs. They are perpetually saturated or flooded from groundwater sources. A major identifying trait of fens is they accumulate peat (decayed vegetation), enabling them to sequester carbon.

Wet meadows: characterized by shallow water tables that persist through much of the growing season and fine-textured soils. Wet meadows rely on water from precipitation, groundwater, and/or surface flow. The high water tables often favor plant species that grow only in wetlands.

In Devils Postpile, the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin River strongly influences wetlands, making them predominantly riparian. The largest of these was selected for monitoring.

monitoring well, Yosemite National Park.

NPS Photo

Wetlands and Impacts of Stressors

Many Sierra Nevada wetlands show impacts from both historic and contemporary human-caused stressors.Land-use changes that alter land cover in surrounding watersheds or change water availability through ditching or groundwater pumping can negatively affect wetland plants and wildlife and alter hydrologic processes.

Grazing: Livestock use in the Sierra Nevada was historically concentrated in wetlands, with very heavy grazing of both cattle and sheep in the late 19th and early 20th centuries leading to severe degradation of some wetlands. Sheep and cattle grazing no longer occur in Sierra Nevada parks, but pack stock use has the potential to cause a range of impacts to wetlands, which include physical changes to wetlands, such as soil compaction or erosion, as well as changes to vegetation and macroinvertebrate communities.

Invasive species: Although high elevation wetlands in the Sierra Nevada have a low incidence of invasive non-native plant species, the threat of invasion is present and likely increasing. Lower elevation wetlands often support introduced pasture grasses, and in recent years some montane meadows in the parks have also been invaded by nonnative grasses.

Climate change: Continued atmospheric warming poses a threat to wetlands primarily by modifying the timing, duration, and magnitude of precipitation and snowmelt in the Sierra Nevada. Changes in precipitation patterns will affect hydrologic regimes and the underlying hydrology of local systems, through changes in the timing and amount of snowmelt. This has the potential to cause dramatic shifts in species composition and abundance within mountain wetlands.

Pollution: Nitrogen pollution from atmospheric deposition has the potential to affect productivity and species composition of wetland vegetation, and depending on seasonal timing, may affect aquatic organisms such as algae and microbes. Effects to these primary producers of the aquatic food chain have the potential to significantly alter all wetland biota. Contaminants, such as pesticides transported via air flow from agricultural areas, have the potential to adversely impact aquatic biota even at low concentrations.

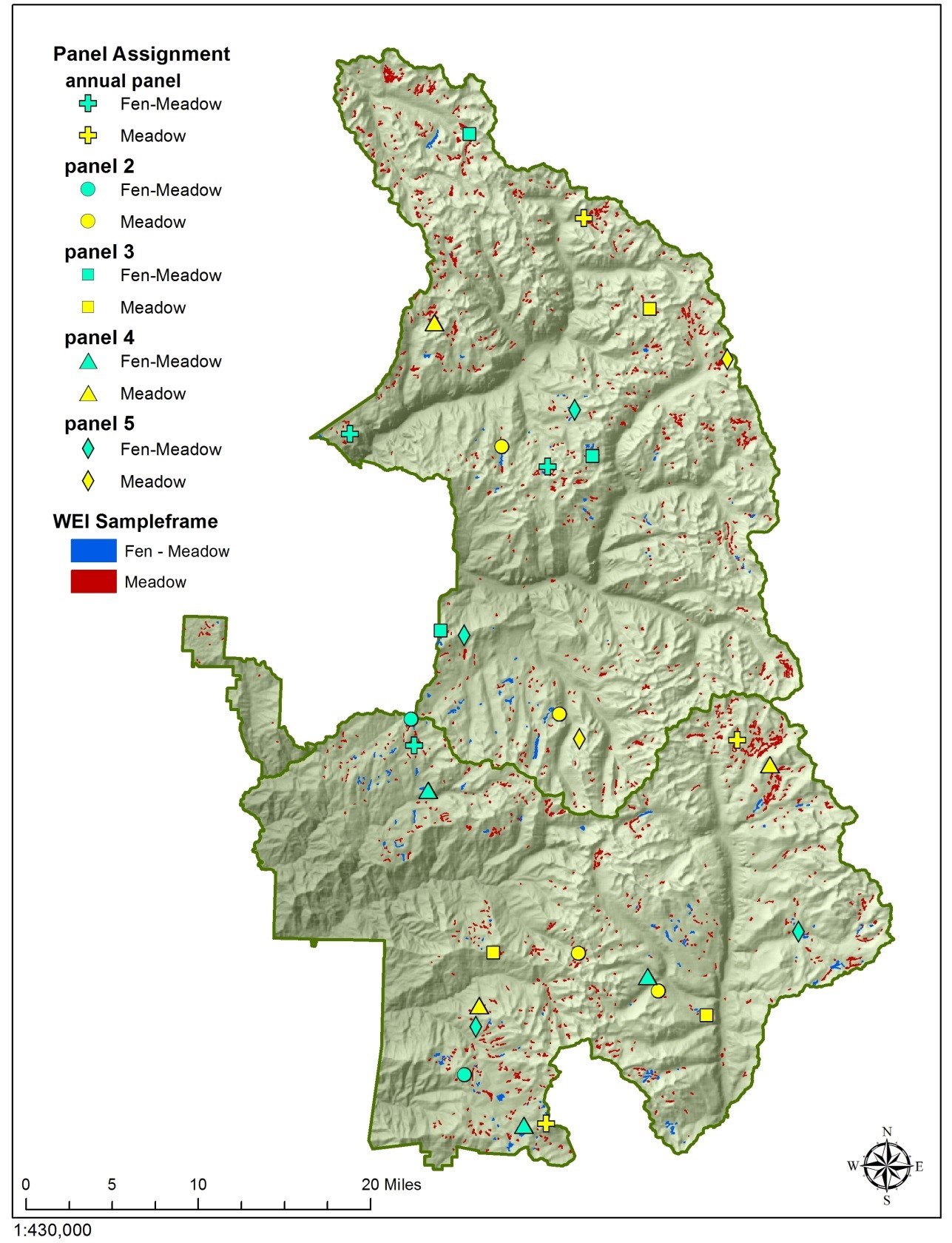

“Annual” panel sites are sampled every year, and sites in panels 2 through 5 are sampled every 4 years.

Monitoring

Sierra Nevada Network and Park staff mapped wet meadows and fens using field data and aerial imagery and then randomly selected monitoring sites from these mapped wetlands (see Figure 1 for sites in Sequoia & Kings Canyon NPs). Monitoring began in 2014. Field crews visit wetland sites from late June through September to collect data addressing the following objectives:- Determine temporal changes in hydrology.

- Estimate temporal changes in species composition and abundance of wetland plants.

- Evaluate temporal changes in the composition and relative abundance of wetland macroinvertebrate populations.

- Quantify changes in bare ground frequency and abundance and determine the most likely causal agents of the observed bare areas.

- Determine temporal changes in non-native plant species and document their location and extent within the wetlands and surrounding area.

NPS Photo / Corey Cann

Management Applications

Information from the wetlands monitoring project will:- Increase understanding of the ecological relationships between wetland biota (invertebrates, vascular and non-vascular plants) and their environment

- Provide reference conditions for those wetlands where pack stock grazing is allowed (protocol only includes ungrazed/lightly grazed sites) or where restoration has occurred

- Provide opportunities to detect new invasions of non-native species early enough for management actions to be effective

- Provide a foundation for research projects to investigate potential causes of observed changes

- Inform park management strategies and generate new interpretive stories to share with the public