Last updated: June 14, 2024

Article

NPS Geodiversity Atlas—Colorado National Monument, Colorado

Geodiversity refers to the full variety of natural geologic (rocks, minerals, sediments, fossils, landforms, and physical processes) and soil resources and processes that occur in the park. A product of the Geologic Resources Inventory, the NPS Geodiversity Atlas delivers information in support of education, Geoconservation, and integrated management of living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) components of the ecosystem.

Introduction

Colorado National Monument is one of the oldest National Park Service sites on the Colorado Plateau. It was proclaimed via the Antiquities Act by President William Howard Taft in 1911 for its extraordinary examples of erosional landscapes. The purpose of the monument is to provide for the preservation, understanding, and enjoyment of its natural and cultural resources as showcased by its extraordinary erosional, geological, and historical landscapes reflective of the northern Colorado Plateau.

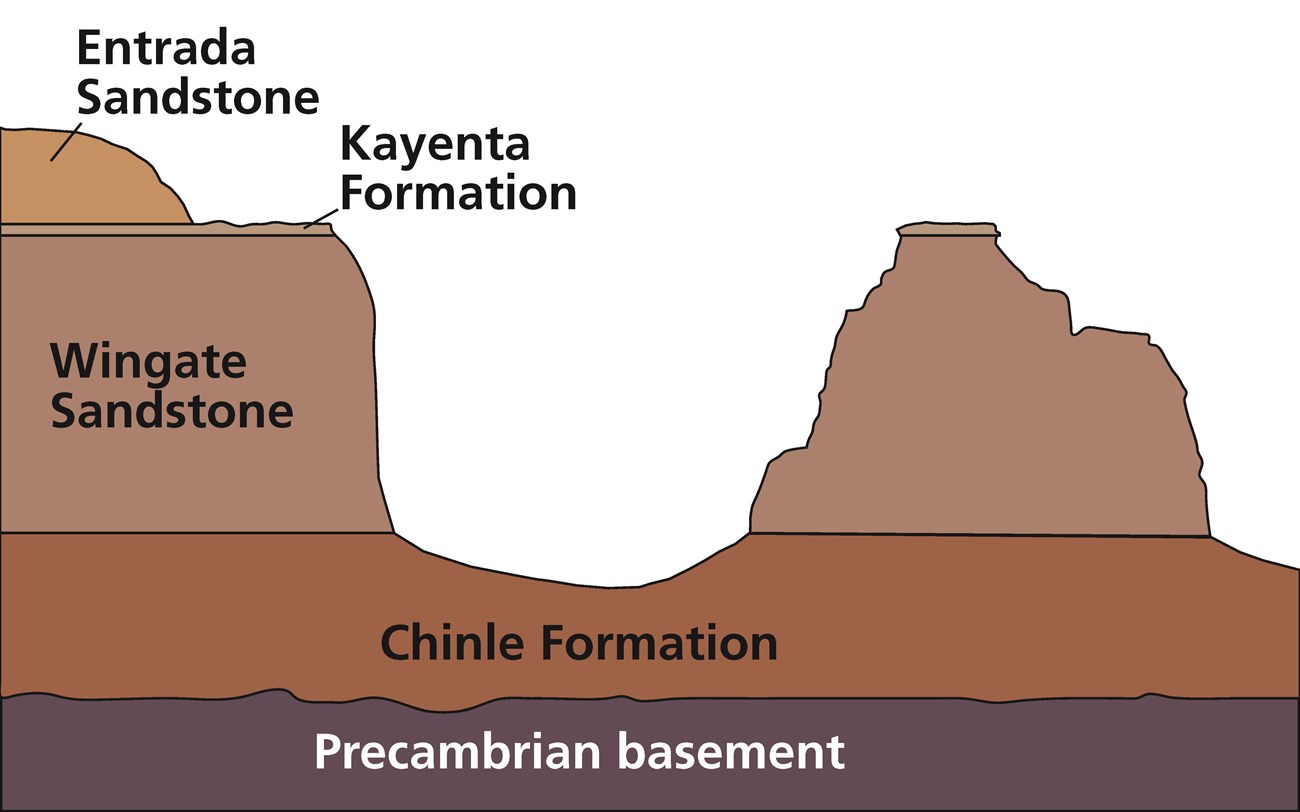

Situated on the northeastern terminus of the Uncompahgre uplift, Colorado National Monument rises approximately 2,000 feet (600 m) above Grand Valley below it. The park contains a series of Mesozoic sedimentary rock units holding up the walls of canyons cut into the edge of the Uncompahgre Plateau. Precambrian metamorphic rocks are exposed in the canyon bottoms.

Colorado National Monument’s outstanding geologic resources include its exposures of the Precambrian basement and Mesozoic sedimentary rocks and its classic landforms formed by arid-land erosion.

Geologic Significance & Geodiversity Highlights

Although Colorado National Monument is a relatively small park at 32 square miles (83 km2) it serves as a great introduction to Colorado Plateau geology and shares several important features and types of geologic resources with other national parks in the region.

-

It contains miles of red cliffs made of the Wingate Sandstone and Kayenta Formation similar to the cliffs in Canyonlands National Park.

-

Other prominent rock units in the park include the Chinle Formation like in Petrified Forest National Park, the Entrada Sandstone like in Arches National Park, and the Morrison Formation like in Dinosaur National Monument.

-

Colorado National Monument contains exposures of the Great Unconformity like in Grand Canyon National Park.

-

The monument has been uplifted along a monocline, akin to the one in Capitol Reef National Park.

-

Colorado National Monument contains an abundance of arid-land landforms such as the spectacular Independence Monument likes found in other Colorado Plateau parks.

Left image

The monocline at Colorado National Monument is evident from the tilt of the Wingate Sandstone (left) to where it has been uplifted on the right where it is nearly horizontal.

Credit: NPS photo courtesy of Allyson Mathis.

Right image

Credit: NPS photo courtesy of Allyson Mathis.

Rim Rock Drive

The 23-mile-long (37-km) Rim Rock Drive hugs the canyon rim providing outstanding views of the monument’s geology, and overlooking Grand Valley and the Book Cliffs. The historic roadway was championed by monument’s founder and first superintendent, John Otto, and was constructed by local workers, staff from other agencies, and the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC), largely using hand tools. The road is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Precambrian Rocks and the Great Unconformity

Colorado National Monument is one of the best places on the Colorado Plateau to view Precambrian basement rocks like those in the Inner Gorge of Grand Canyon National Park and in Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. The basement rocks exposed in Colorado National Monument consist of schist, gneiss, pegmatite, and igneous dikes. The metaigneous and metasedimentary rocks formed between 1,741 and 1,721 million years ago, and were intruded by dikes about 1,400 million years ago.

In Colorado National Monument, the approximately 220-million-year-old Chinle Formation directly overlies the Precambrian basement rocks. The unconformity (gap in the rock record) here spans 1,500 million years, which is approximately one third of Earth’s history.

The unconformity between Precambrian rocks and sedimentary rocks in Grand Canyon was named the Great Unconformity by geologist John Wesley Powell, and this terminology is used in other places in the Southwest.

The Great Unconformity in Colorado National Monument actually covers a longer period of time than the one in Grand Canyon National Park, which is 1,200 million years or less. It is also much easier to view at Colorado National Monument since the park road passes by it in several locations including near the west entrance, although it is poorly exposed because the Chinle Formation is not resistant to erosion.

Left image

The Great Unconformity in Fruita Canyon near the West Entrance of Colorado National Monument. The Chinle Formation is much less resistant to erosion than the underlying Precambrian basement, making the unconformity itself relatively poorly exposed.

Credit: NPS photo courtesy of Allyson Mathis.

Right image

Credit: NPS photo courtesy of Allyson Mathis.

Paleontological Resources

With its sedimentary rock record spanning much of the Mesozoic and recording diverse depositional environments, Colorado National Monument has a rich fossil record.

Most of the sedimentary rock units exposed in the monument contain fossils. Only the Dakota Sandstone (Naturita Formation) and Entrada Sandstone have not had fossils documented within the monument boundary, although the Dakota Sandstone possibly contains fossils and bioturbation is present in the Entrada Sandstone.

The Morrison Formation’s fossil record within Colorado National Monument is particularly significant. Exposures in western Colorado contain many important paleontological sites that provide information about the Morrison Formation’s terrestrial ecosystems. Dinosaur fossils (both body and trace fossils), other vertebrate fossils, petrified wood and other plant fossils, and invertebrates are known from the Morrison Formation from within monument boundaries.

Other fossils found in Colorado National Monument include:

-

Chinle Formation: Root traces and rare vertebrate fossils

-

Wingate Sandstone: Tracks of dinosaurs and other vertebrates

-

Burro Canyon Formation: Dinosaur bone fossils, petrified wood

Related Links

All NPS fossil resources are protected under the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-11, Title VI, Subtitle D; 16 U.S.C. §§ 470aaa - 470aaa-11).

Geologic Setting

Colorado National Monument is located along the northern terminus of the Uncompahgre Plateau in western Colorado. It sits above Grand Valley carved by the Colorado River which flows a short distance north of the monument boundary.

Colorado National Monument is in the northern part of the Colorado Plateau, one of 25 physiographic provinces in the contiguous United States. The Colorado Plateau has an overall high elevation, thick continental crust, and has experienced relatively little structural deformation with the exception of Laramide features such as the Uncompahgre Uplift in Colorado National Monument. The plateau is characterized by an arid to semiarid environment, great topographical relief, and excellent exposures of the rock record.

Colorado Plateau

The Colorado Plateau covers approximately 130,000 square miles (337,000 km2) across the Four Corner states of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. The greatest concentration of national park sites in the country, including 30 units of the National Park System, is found on the Colorado Plateau.

The Colorado Plateau is divided into six sections, each with a distinctive character. Colorado National Monument is near the boundary of the Canyon Lands section and the Uinta Basin section of the Colorado Plateau. The Canyon Lands section is dominated by gently tilted sedimentary rock layers that have been intricately carved into canyons. The Uinta Basin section contains extensive exposures of Cretaceous mudstones and sandstones including the Mancos Shale and Mesa Verde Group exposed in the Book Cliffs north of the monument.

The Colorado Plateau has a complex geologic history and experienced multiple periods of uplift. Much of the uplift of the Colorado Plateau region occurred during the Laramide orogeny, a mountain-building event that impacted most of the interior west, between 70 and 40 million years ago. Unlike the neighboring Rocky Mountains, the Colorado Plateau was relatively undeformed, experiencing general uplift and the formation of broad upwarps and downwarps throughout the region. Colorado National Monument is located on the northeastern flank of the Uncompahgre Uplift and a short distance south of the Uinta Basin downwarp.

Uncompahgre Plateau

Colorado National Monument is located along the northern edge of the Uncompahgre Plateau, an area that has undergone at least two periods of mountain-building or uplift throughout geologic time.

-

Ancestral Rocky Mountains: A series of uplifts, including that of the Uncompahgre Plateau, during the Late Paleozoic (320-280 million years ago) that were mostly in Colorado that were eroded away during the Mesozoic Era.

-

Laramide orogeny: A widespread mountain-building event that impacted the American west between 70 and 40 million years ago and that reactivated uplift of the Uncompahgre Plateau.

Geologic History and Stratigraphy

Rocks exposed in Colorado National Monument range in age from 1,741 million years (1.741 billion) old to approximately 100 million years. However, there is a significant gap in time in its rock record between the Precambrian basement rocks and the Triassic Chinle Formation, the oldest sedimentary rock unit exposed in the monument.

The sedimentary rocks exposed in Colorado National Monument are all Mesozoic in age, ranging from the Late Triassic through the Cretaceous.

The geologic history of the Colorado National Monument (and that of the entire Colorado Plateau) changed dramatically with the onset of the Laramide orogeny, the mountain building event that formed the Rocky Mountains and the Uncompahgre Uplift, and uplifted the entire Colorado Plateau.

The erosional events that formed the park’s landforms are very recent, occurring within the last few million years.

Illustration by Allyson Mathis.

Precambrian (Proterozoic Era)

The Precambrian basement rocks exposed in Colorado National Monument were mostly formed during orogenies that occurred during the accretion of volcanic island arcs (the Yavapai Provence) to the North American craton (Laurentia) between 1,800 and 1,700 million years ago (1.8-1.7 billion years ago). The igneous and metasedimentary rocks of the Yavapai Provence were formed reflect a complex geologic history consisting of multiple volcanic arcs that formed and then collided with new continental crust along the southern edge of the continent.

Colorado National Monument’s Precambrian basement rocks consists of two main types: metaigneous gneiss and dark migmatitic schist.

These rocks were later intruded by lamprophyre dikes about 1,400 million years ago. Lamprophyres are a type of mafic intrusive rock with very high potassium contents. These dikes probably relate to widespread crustal melting that occurred in Southwest during this time.

Paleozoic Era

The Colorado National Monument region was part of the Ancestral Rocky Mountains during the Late Pennsylvanian and Early Permian.

The Ancestral Rocky Mountains consisted of the Uncompahgre Plateau, the Front Range of Colorado, and other uplifts in Wyoming, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. They consisted of northwest-trending uplifts that were broadly related to compressional forces, although the full tectonic environment is not well understood as it was distal to plate margins.

The Uncompahgre Plateau was the westernmost of these uplifts. Sediments eroded from the highlands were deposited in the Paradox Basin to the southwest and to the Central Colorado Trough to the east.

Its location on the Uncompahgre Plateau is why Colorado National Monument doesn’t contain any Paleozoic Rocks. The oldest sedimentary rock unit in the monument is the Triassic Chinle Formation which was deposited after considerable erosion of the Ancestral Rockies had occurred so that the area was then a depositional basin.

Mesozoic Era

The sedimentary rocks exposed in Colorado National Monument were deposited during the Mesozoic Era.

Mesozoic rock units exposed in Colorado National Monument include (from oldest to youngest):

The Chinle Formation which unconformably overlies the Precambrian basement is the oldest sedimentary rock unit in Colorado National Monument. The Chinle Formation is relatively thin (approximately 90 ft; 27 m) in the monument and only consists of the informally named red siltstone unit. It is mostly reddish mudstone and siltstone that was deposited on a vegetated floodplain or mudflat, with shallow ponds and streams. The Chinle Formation in the monument was deposited in the Late Triassic at about 205 million years ago.

-

https://www.moabhappenings.com/Archives/Geology202106-ChinleFormation.htm

The Triassic-Jurassic Wingate Sandstone is the main cliff-forming unit in Colorado National Monument. The Wingate is an eolian sandstone deposited between 202 and 195 million years ago. Only the lower part of the Wingate Sandstone was deposited near the end of the Triassic; most of the formation was deposited in the early Jurassic. The Wingate Sandstone is about 330 feet (100 m) thick.

The Jurassic Kayenta Formation was deposited in a fluvial environment where large sandy braided river systems flowed to the west out of the Ancestral Rocky Mountains. The Kayenta has low-angle cross-bedding typical of fluvial deposition. The unit is very resistant to erosion and it caps most of the canyon rims and many of the rock spires (monuments) in Colorado National Monument. The Kayenta Formation is between 80 ft (25 m) and 50 ft (14 m) thick.

The Jurassic Entrada Sandstone consists of two members in Colorado National Monument. The lower portion Slick Rock Member and is about 100 ft (33 m) thick. The Slick Rock Member is eolian in origin and is the unit containing most of the arches in Arches National Park, which is about 55 miles (90 km) to the southwest. The informally named upper unit, the board beds, consists of about 45 ft (13 m) of light-colored thin slabby layers of sandstone and mudstone.

The Jurassic Wanakah Formation consists of approximately 30 ft (9.4 m) of mostly slope-forming mudstone in Colorado National Monument.

The stratigraphy between the Wanakah Formation and the Morrison Formation is problematic and not all geologists are in agreement about correct stratigraphic terminology. There is a dispute about whether strata mapped as the Wanakah Formation should be instead assigned to the lower Summerville Formation. Some geologists have mapped a lower member (Tidwell Member) as part of the Morrison Formation and others recognize it part of the Summerville Formation.

With the exception of the Tidwell Member, which is sometimes assigned to the Morrison Formation and to the Wanakah Formation by other researchers, the Morrison in Colorado National Monument consists of two members: the lower Salt Wash Member and the upper Brushy Basin Member. The Salt Wash Member is dominated by channel sandstones and the Brushy Basin Member consists predominantly of mudstones with lesser amounts of sandstone deposited largely in floodplain and lacustrine environments. It was deposited between about 155 and 148 million years ago and contains a wealth of vertebrate and invertebrate fossils as well as petrified wood and other plant fossils.

The Salt Wash Member is about 100 ft (31 m) thick and the Brushy Basin Member is about 310 ft (95 m) in the monument.

In Colorado National Monument, the Cretaceous Burro Canyon Formation consists mostly of sandstones in its lower portions with an upper portion consisting mostly of mudstones. It was deposited in river channels, on floodplains, and in lacustrine environments. The formation is about 130 ft (29 m) thick.

The Cretaceous Dakota (Naturita) Formation is the youngest bedrock unit exposed in Colorado National Monument. It is exposed along the western park boundary where it is about 100 ft (31 m) thick. It consists of a basal conglomerate, followed by a grayish coaly mudstone interval, and then a light-colored sandstone interval that were deposited during the transgression of the Western Interior Seaway in western Colorado.

Although this Cretaceous transgressive sequence has long been known as the Dakota Sandstone in western Colorado, careful application of stratigraphic nomenclature conventions as defined in the North American Stratigraphic Code means that rocks on the east and west coasts of the Western Interior Seaway cannot belong to the same rock unit according to the definition of a formation. The Dakota Sandstone was first described from outcrops along the Missouri River on the opposite coast of the Western Interior Seaway and the similar rocks in Colorado National Monument are not continuous with those rock units. The Naturita Formation was described from exposure near the western Colorado town on Naturita where these rocks were described in the 1960s and some stratigraphers think that this terminology should be used for these packages of transgressive rocks.

The Cretaceous Mancos Shale is not exposed in Colorado National Monument, but it is in the neighboring Grand Valley and in the Book Cliffs to the north, both areas that are major part of the viewshed from many locations in the monument and along the Rim Rock Drive.

The Mancos Shale consists mostly of marine shales deposited in the Western Interior Seaway between about 95 and 85 million years ago. In western Colorado, the unit is more than 4,000 feet thick.

Cenozoic Era

The Cenozoic geologic history of the Colorado National Monument area is strikingly different than its previous geologic history. Instead of being part of depositional basins, as it was throughout much of the Late Paleozoic and Mesozoic, western Colorado was impacted by the tectonic and erosional events that have shaped the entire Intermountain West, and ultimately led to rise of the Uncompahgre Plateau.

Uplift of the Colorado Plateau

Sedimentary rocks exposed in Colorado National Monument were deposited at or near sea level, but now stand as high as 7,000 feet (2,100 m) in elevation.

The Colorado Plateau has a complex geologic history and experienced multiple periods of uplift.

Most of the uplift of the Colorado Plateau occurred during the Laramide orogeny between 70 and 40 million years ago.

The Laramide orogeny impacted a wide area much broader than what occurs above a typical subduction zone. The unusual tectonics of the Laramide orogeny was caused by the subduction of a large oceanic plateau within the Farallon plate, where unusually thick oceanic crust caused the subduction angle to shallow so that orogenic forces extended far from the tectonic boundary.

In addition to regional uplift, the Laramide orogeny formed several major uplifts including the Uncompahgre uplift. Monoclines (segments of folds that have much steeper dips than surrounding structures) typically bound one of more limbs of Laramide uplifts. One of these monoclines is associated with the Redlands Fault and has uplifted northeastern part of Uncompaghre Plateau in Colorado National Monument.

The Mid-Cenozoic Uplift of the Colorado Plateau was the first of two additional periods of uplift consequent to the tectonics of the Laramide orogeny. It occurred between 35 and 25 million years ago, an interval during which shallow igneous intrusions formed the three laccolithic mountain ranges (La Sal, Abajo, and Henry) in Utah that are to the southwest. Hot asthenosphere inflowing above the sinking Farallon slab underneath the Colorado Plateau caused the surface uplift.

The most recent period of tectonic uplift took place within the last 10 million years due to complex mantle processes following the subduction of the Farallon plate.There is evidence of further uplift of the Uncompahgre Plateau during the last 3 to 4 million years or so, with as much as 2,100 feet (640 m) of differential uplift.

Landscape Evolution

The landscape of Colorado National Monument is geologically very young as indicated by its steep-walled canyons and the overall geomorphology of the Colorado Plateau region.

In the big picture, landscape evolution on the Colorado Plateau was initiated within the last 5 to 6 million years after the integration of the upper Colorado River to the Gulf of California. Important evidence that constrains the age of the modern Colorado River is present on Grand Mesa near Grand Junction, Colorado where Colorado River gravels are present underneath a 10-million year old lava flow.

The entire Colorado Plateau has undergone extensive erosional stripping with up to 5,000 to 13,000 feet (1,500 to 4,000 m) of erosion centered over the central plateau region, with lesser amounts of erosion progressively towards its edges.

Differential erosional is an important component of landscape evolution in Colorado National Monument. Differential erosion is that which occurs at different rates in rocks of varying resistance to erosion. Harder rocks like the Wingate Sandstone and Kayenta Formation erode at slower rates relative to softer units like the Chinle Formations. Resistant layers can form hard cap rocks that hold up mesas, buttes, and spires and protect softer units below them from erosion.

NPS photo courtesy of Allyson Mathis.

Geologic Features and Processes

Redlands Fault Complex

The Redlands Fault Complex is included in the US Geological Survey’s Quaternary Fault and Fold Database. The complex consists of three faults and two monoclines that mark the northeastern terminus of the Uncompahgre uplift. Although there are no Quaternary deposits present in the area that can show offset, faults associated with the Uncompahgre uplift are generally considered to have had Quaternary movement.

The Redlands Fault is a high-angle reverse fault. Strata deformed over the fault have been deformed into an S-shaped fold or a monocline.

- USGS—Quaternary Fault and Fold Database of the United States

- Colorado N.M.—Uplift: Why We Rise Above the Valley

Monuments and Spires

NPS photo courtesy of Allyson Mathis.

Monuments, towers, and spires are synonyms for isolated rock pillars or pinnacles with vertical precipitous sides. Several imposing towers stand in Monument Canyon below Rim Rock Drive.

With the exception of the narrow band along the Redlands Fault Complex where the rock units are steeply dipping, strata in Colorado National Monument are nearly horizontal. The Uncompahgre Plateau is capped by the resistant Wingate Sandstone and Kayenta Formation which hold up nearly vertical cliffs above the softer Chinle Formation. As erosion and cliff retreat proceeds, the harder cap rocks are uncut by the softer rocks below them. Headward erosion of tributary drainages reaches up into the plateau forming promontories between canyons. Eventually pieces of these promontories get cut off from one another leaving free-standing towers.

Independent Monument is the largest rock spire in Colorado National Monument, standing approximately 450-feet (140-m) tall. The monument’s first superintendent John Otto climbed this tower on July 4, 1911 leading to an annual tradition that continues to this day.

Other Geodiversity Values

The geologic significance of Colorado National Monument impacts all its natural and cultural resources. Other geodiversity values include well-developed biological soil crusts, seeps and springs, and desert varnish and other rock surface coatings.

Biological Soil Crust

The Colorado Plateau contains some of the best-developed biological soil crusts in the world. Biological soil crusts consist of communities of microorganisms including cyanobacteria, mosses, lichen, green algae, and microfungi, and bacteria and form in arid and semi-arid areas. They are integral to the monument’s ecosystems because they fix nitrogen and provide other nutrients as well as inhibiting soil erosion. They develop well on the sandy soils found in the park.

Biological soil crust are very susceptible to crushing from human activities. Footprints and tire tracks can destroy crusts. The damage may take decades to repair and damaged crusts may never fully recover.

Protect soil crusts by staying on established roads and trails and protecting trailside vegetation and soils. When hiking off-trail, stay on bare slickrock or walk in dry washes where crusts do not form.

Springs and Seeps

Springs and seeps along with the hanging gardens that they support are very important to the ecosystems of Colorado National Monument because they are reliable water sources in a place where they are rare. The eolian Wingate Sandstone high porosity and permeability, and hanging gardens may be found along canyon walls near the contact with the underlying Chinle Formation.

Springs and seeps in the monument also are sourced from fractures in the Precambrian basement rocks or from alluvial deposits and are found in canyon bottoms.

Desert Varnish

Stable sandstone surfaces in Colorado National Monument are usually coated with a variety of thin rock coatings collectively known as desert varnish. Desert varnish consists rock varnish, heavy metal (iron and manganese) skins, silica glaze and other components. Rock varnish itself consists predominantly of clay minerals with a substantial proportion of iron and manganese oxides and minor amounts of other components. It ranges in color from red to black with higher concentrations of manganese producing varnishes that are more black in appearance.

Desert varnish may preferentially form where water streaks down cliff faces. In Colorado National Monument, desert varnish is most noticeable on the cliffs of the Entrada and Wingate sandstone where brown to black streaks make a stark visual contrast to the lighter-colored bedrock.

Geohazards

Geohazards present in Colorado National Monument include those associated with slope stability, rock fall and other mass wasting events, as well as flash flooding during intense rainfall events. Geohazards are also present at abandoned mineral lands, including radioactivity (including radon), unsafe structures, cave-ins, deadly gases and oxygen deficiency, and potentially unstable explosives.

Seismic Hazards

The US Geological Survey’s Quaternary Fault and Fold Database includes Redlands Fault Complex.

Overall, Colorado National Monument has a moderate seismic hazard. The USGS 2014 Seismic Hazard Map indicates that the Colorado National Monument area has a 2% chance that earthquake peak ground acceleration of between 12 and 14 %g (percent of gravity) being exceeded in 50 years. This peak ground acceleration is roughly equivalent to VI on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale. The expected number of damaging earthquake shaking in the vicinity of Capitol Reef National Park National Park in 10,000 years is between 4 and 10.

Caves and Karst

Colorado National Monument has not been identified by the National Park Service as having either karst or pseudokarst.

Related Link

All NPS cave resources are protected under the Federal Cave Resources Protection Act of 1988 (FCRPA)(16 U.S.C. § 4301 et seq.).

Abandoned Mineral Lands

Nine Abandoned Mineral Lands (AML) sites have been documented by the National Park Service in Colorado National Monument. These sites contain 10 mining features, one of which was mitigated and do not require mitigation. The sites are either hard rock mines or burrow pits.

Winzes (steeply inclined passageways) in the Kodel Gold Mine were backfilled by the National Park Service to preserve the historical integrity of the site while removing the primary hazards. The Kodel Gold Mine is located in the Precambrian basement rocks, but it doesn’t appear that there was actual production from the mine.

NPS AML sites can be important cultural resources and habitat, but many pose risks to park visitors and wildlife, and degrade water quality, park landscapes, and physical and biological resources. Be safe near AML sites—Stay Out and Stay Alive!

Related Link

Burghardt, J. E., E. S. Norby, and H. S. Pranger, II. 2014. Abandoned mineral lands in the National Park System—comprehensive inventory and assessment. Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRTR—2014/906. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. [PDF]

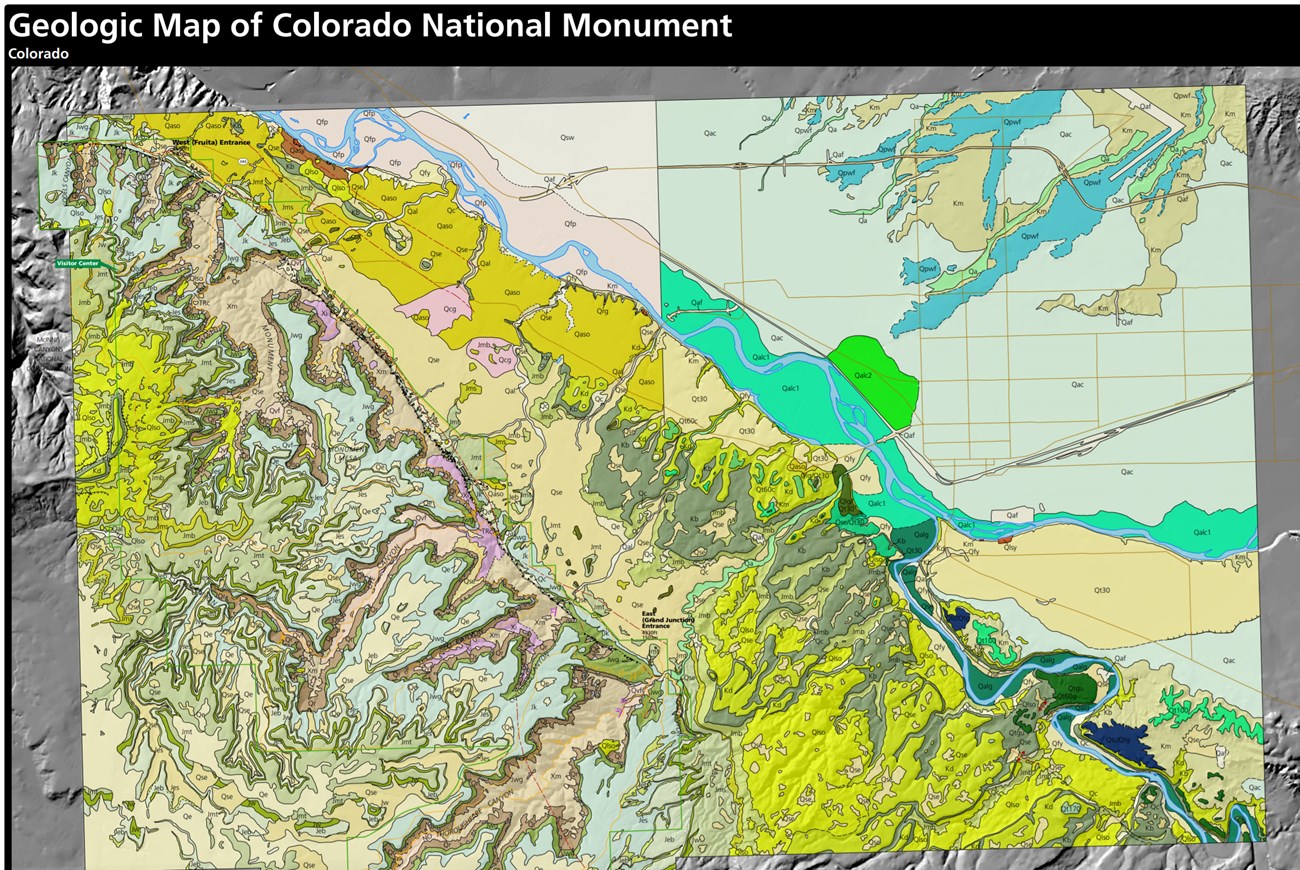

- Scoping summaries are records of scoping meetings where NPS staff and local geologists determined the park’s geologic mapping plan and what content should be included in the report.

- Digital geologic maps include files for viewing in GIS software, a guide to using the data, and a document with ancillary map information. Newer products also include data viewable in Google Earth and online map services.

- Reports use the maps to discuss the park’s setting and significance, notable geologic features and processes, geologic resource management issues, and geologic history.

- Posters are a static view of the GIS data in PDF format. Newer posters include aerial imagery or shaded relief and other park information. They are also included with the reports.

- Projects list basic information about the program and all products available for a park.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 2792. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

A NPS Soil Resources Inventory project has been completed for Colorado National Monument and can be found on the NPS Data Store.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 2842. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

Related Links