Last updated: February 10, 2022

Article

Honoring Indigenous Heritage in Chicago

By Evelyn Moreno

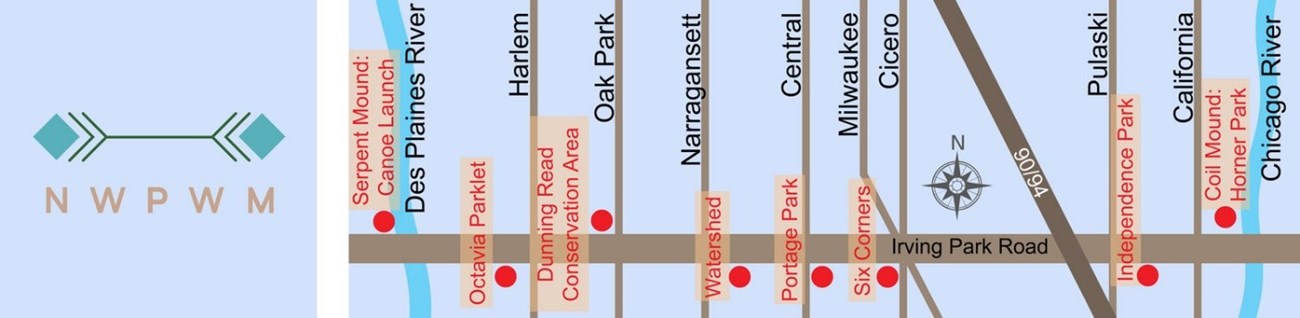

On Indigenous People’s Day nearly 400 people gathered at Schiller Park, situated along the Des Plaines River, for the unveiling of the Serpent Mound. The mound, built from soil and ancestral dirt from various tribal lands in the nation, is one of two mounds that will connect the Des Plaines River to the Chicago River along the 9-mile stretch of Irving Park Road.

The mound is part of the Northwest Portage Walking Museum, a project that aims to shed light on the natural environment and cultural history of Chicago, a city that is home to the third-largest urban Native American population in the United States.

“One of the things that we struggle with the most here is that Illinois tends to forget that this is Indian land and always has been,” said Heather Miller, the executive director of the American Indian Center in Chicago. “We are constantly at the forefront reminding folks that native Americans have always called this area home… We have tribes that are still living here, we have a really thriving native community and so the importance of this particular project is that the way we set it up is that it’s bookended by Native American perspective.”

The idea for the project began when neighbors came together to prevent the demolition of the city’s last working blacksmith shop in hopes of converting it into a museum. However, when city officials approved a proposal to build an apartment building in its place, Portage Park Neighborhood Association president Patty Conroy said community members were inspired to create a walking museum lined with public art to portray the history of the city.

At a community meeting for the Great Rivers Chicago initiative, a vision led by the Metropolitan Planning Council to connect people to the rivers, Conroy shared how the neighborhood association hoped to connect Chicago’s two rivers through Irving Park Road, a route that not only links several neighborhoods but also connects residents to river recreation opportunities.

The Metropolitan Planning Council applied for assistance from the National Park Service – Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance program to foster conversations in neighborhoods about river related projects.

Michael Mencarini, a project specialist for the National Park Service, worked with Conroy and Portage Park Neighborhood Association members to help evolve their idea by identifying strategic goals, facilitating conversations with stakeholders and local government entities as well as finding financial resources.

A steering committee consisting of members of the Portage Park Neighborhood Association, the American Indian Center and Chicago Public Art Group formed and were awarded a grant from the Chicago Community Trust as part of the Great Rivers Chicago initiative to begin planning and developing for the walking museum.

With the grant, the committee commissioned indigenous futurist artist Santiago X, an enrolled member of the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana and Indigenous Chamorro from the island of Guam. After gathering feedback during community and youth workshops on potential public art pieces to showcase, Santiago X proposed mounds at the two river sites as a way to pay homage to the ancestral practice.

“I don’t see the presence of the indigenous point of view, the indigenous architect,” Santiago X said in an interview with the Chicago Tribune. “...I don’t see the presence of indigenous place makers in any of these cities, so I would like to return to that or at least catalyze the movement to create indigenous spaces again.”

Mencarini served as a liaison between the steering committee and the Metropolitan Planning Council and assisted the organizations in acquiring resources to build the mound as well as permits to use county land.

“Mike [Michael Mencarini] has been a great team member,” Miller said. “He’s been such an advocate for this project and he’s been so helpful in organizing different elements. None of us on the committee are landscapers, none of us are experienced in getting permits or contracts or anything like this… Every time we had a question or something arose, Mike helped us figure it out.”

Installing the Serpent Mound was one goal the American Indian Center, Chicago Public Art Group and the Portage Park Neighborhood Association had been working toward for about two years. Miller said they believe the earthwork is the first effigy mound to be built by Native Americans in North America in the last 500 years and is intended to act as it would have back in the day – as a wayfinding. Though completed, the mound is expected to change and grow over time as the indigenous plants that were planted along its body take root.

Next year, the steering committee hopes to raise funding to build the second mound which will resemble a coiled body of a snake along the western banks of the Chicago River in Horner Park. The coil mound will be about eight to nine feet high and will have a spot at the top to encourage visitors to walk up the “spine of the serpent” and reflect.

“The big picture of the project is to connect communities, connect people and connect cultures,” said Maryrose Pavkovic, the managing director of the Chicago Public Art Group.

The mounds at opposite ends of Irving Park Road are not the only public art pieces however. Though they will serve as anchors for the interactive walking museum trail, more art, educational and recreational pieces will be added in the months and years to come. By the end of this year a sculpture will be installed at the Dunning Read Conservation Area.

"It has been great to see this project evolve from an early idea into a unique way to think about how community place-making can connect us to the places and rivers we call home,” Mencarini said. “Partners at the American Indian Center of Chicago, Portage Park Neighborhood Association and the Chicago Public Art Group have been outstanding advocates for this project, and hopefully the momentum from the Serpent Mound will continue as they work towards their goal of telling the cultural and environmental story of Chicago's Northwest Side."