Last updated: July 5, 2022

Article

Northern Spotted Owl Monitoring at Mount Rainier National Park

NPS/Emily Brouwer

NPS/Anna Mangan

Why do we monitor Northern Spotted Owls?

Mount Rainier National Park is home to a small population of the Northern Spotted Owls (Strix occidentalis caurina) that has been monitored annually since 1997. The spotted owl was listed as Endangered in Washington state in 1988, and later listed as federally threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1990 under the Endangered Species Act after habitat loss, attributed to timber harvest, resulted in the decline of Northern Spotted Owl populations across their range (Washington, Oregon, and California). Federal status provided special protections for the spotted owl and their habitat throughout their range. Currently, there are 36 historic territories that are monitored at Mount Rainier National Park. Northern Spotted Owl monitoring enables biologists and park managers to get accurate annual population estimates of adult and juvenile spotted owls in the park so informed conservation measures can be taken to preserve the species within park boundaries, and can contribute to the overall understanding of spotted owl population dynamics.

NPS/Anna Mangan

How do we monitor Northern Spotted Owl populations?

A team of dedicated field biologists spend April through September hiking through old growth forests at Mount Rainier where spotted owls are suspected to occur. Northern Spotted Owls are found in old growth forest habitat that is typically comprised of 200+ year-old Douglas Fir, Western Hemlock and Western Red Cedar trees, which provides various layers of shrub and tree canopy cover for owls to hunt and nest in. When an owl replies by hooting in response to a surveyor, it is located and individually identified. All adult and juvenile spotted owls are captured and banded with a USFW number band, as well as a plastic color band that enables biologists to identify individual owls without recapturing them. Once the owl(s) have been identified, field biologists determine if they are nesting by feeding four mice to the owl. If nesting, it is typical for the owl to bring at least one of these mice back to a nesting female or to the fledged young. If non-nesting, owls will either eat the mice, or cache them in a nearby location to eat later. In recent years, we have also started deploying automated recorder units (ARU’s) near spotted owl activity site centers. The ARU’s record sound passively within spotted owl territories during dusk and night hours for up to two weeks at a time, increasing the probability of detecting Northern Spotted Owls or Barred Owls that may be in the area but are not responding to surveyors during the day.

NPS/Russ Gibbs

What does monitoring tell us about Mount Rainier’s Northern Spotted Owls?

The probability that a Northern Spotted Owl territory at Mount Rainier was occupied by a single or pair of spotted owls has decreased by 50% between 1997 and 2016. Further, the probability that a territory was colonized (a territory that was unoccupied previously, becomes occupied by an owl in the current year) has been reduced to 9% in 2016. This indicates that once spotted owls vacate territories, there is a very small chance that they will be occupied by owls again, and the overall population of spotted owls at the park may continue to decrease. While loss of spotted owl habitat is still a concern (primarily from fires), the greatest threat to Northern Spotted Owl populations is the closely related Barred Owl. Barred Owls are larger, aggressive, produce more young, and are generalists with respect to habitat and diet. Many studies have suggested that these attributes, among others, are what enable Barred Owls to outcompete spotted owls for shared resources. Barred Owl detections at Mount Rainier National Park have increased from ~30% in 1997 to over 60% in recent years, while detections of Northern Spotted Owls continue to decrease. Additionally, a recent study at Mount Rainier revealed that Barred Owl presence within a spotted owl territory negatively influences the chance that a spotted owl pair will breed. If spotted owl breeding declines, fewer young owls will be available on the landscape to colonize territories, and the overall population of spotted owls at the park will likely decline. Although Barred Owls were documented in Washington as early as 1965, the first Barred Owl at Mount Rainier National Park was not documented until 1986. However, Barred Owls have been detected every year since this time, so spotted owls have likely been competing with Barred Owls for resources at Mount Rainier since the late 1980’s. With a small and aging population of reproducing adult spotted owls at MRNP (18 territorial adults were found in 2017), the negative relationship between Barred Owls and spotted owl breeding propensity (the probability that a pair of spotted owls breeds) is concerning for the long-term survival of the Northern Spotted Owl population at Mount Rainier National Park.

NPS Photo.

How can you help Northern Spotted Owls?

Mount Rainier's old growth forests have remained largely in-tact because of federal protection since 1899. This has left nearly 82,000 acres of contiguous Northern Spotted Owl forest habitat available at Mount Rainier National Park for spotted owls to use for roosting and nesting. That is a lot of ground searching for a small crew of seasonal field biologists! While we cover a large amount of this area during the season on foot, and also use automated recorder units to help us detect spotted owls, reports from the public of Northern Spotted Owl or Barred Owl audio or visual sightings are always helpful!

NPS Photo.

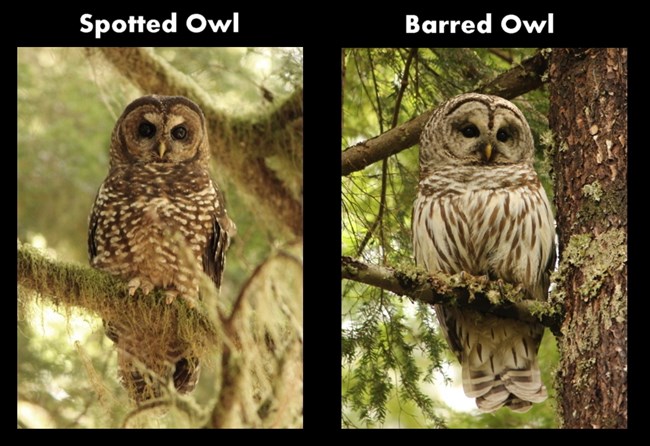

You can enter potential spotted owl sightings on eBird from home, or submit a Mount Rainier Wildlife Obervation report. Getting accurate descriptions of feather patterns, especially from the front of the bird is best, and including a picture helps park biologists verify sightings and monitor populations more effectively. Further, you can educate others about the critical state of the Northern Spotted Owl population within Mount Rainier National Park and across their range, and encourage federal managers to take proactive approaches to preserving the species from going extinct. Use the provided links to compare differences between territorial hoots of Northern Spotted Owls and Barred Owls, as well as the visual difference between the front and back of each owl.

Northern Spotted Owl Calls

Barred Owl Territorial Call