Last updated: May 9, 2023

Article

New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School: From Freedom of Choice to Integration (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

In the early 1830s, Thomas "Daddy" Rice, a white actor, began caricaturing blacks in his stage performances. One of his characters, a black man named "Jim Crow," would become synonymous with legalized segregation in this country. During the so-called Jim Crow era of the late 19th through mid-20th centuries, separation of the races in public transportation, parks, restaurants, and other public places was either required by law or permitted as a cultural norm. Public schools were no exception to this rule. School systems across the South were typically segregated. After 1896 these schools were supposed to adhere to the separate but equal rule established by the United States Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, but in reality, the schools for blacks were most often inferior to the schools for whites. It was this inequality that galvanized the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to begin the process of dismantling Jim Crow through the court system in the early 20th century.

The New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School, located in New Kent County, Virginia, are associated with the most significant public school desegregation case the U.S. Supreme Court decided after Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. While Brown determined that separate schools were inherently unequal, it did not define the process by which schools would be desegregated. The 1968 Charles C. Green, et al., v. County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia, et al. decision defined the standards by which the Court judged whether a violation of the U.S. Constitution had been remedied in school desegregation cases. Henceforth, a decade of massive resistance to school desegregation in the South from 1955-1964 would be replaced by an era of massive integration from 1968-1973, as the Court placed an affirmative duty on school boards to integrate schools. The New Kent and George W. Watkins schools illustrate the typical characteristics of a southern rural school system that achieved token desegregation following the Brown decision. They stand as a symbol to the efforts of the modern Civil Rights Movement of 1954-1970 to expand the rights of black citizens in the United States.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Historic Landmark Nomination, "New Kent School and George W. Watkins School" (with photographs), as well as oral interviews, newspaper accounts, and other primary sources. New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School: From Freedom of Choice to Integration was written by Jody Allen, Brian Daugherity, and Sarah Trembanis, Ph.D. candidates at the College of William and Mary, with assistance from Frances Davis, Na' Dana Smith, and Megan Walsh, Class of 2002, New Kent High School in New Kent County, Virginia. The lesson was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

This lesson plan was made possible by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Public Policy (VFH) as part of its African-American Heritage Program, including the African-American History in Virginia Grant Program, the African-American Heritage Database Project, and the African-American Heritage Trails Program, a partnership between VFH and the Virginia Tourism Corporation. Since 2018, VFH has been known as Virginia Humanities. For more information, contact Virginia Humanities, 145 Ednam Drive, Charlottesville, VA 22903, or visit Virginia Humanities' website.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in American History courses in units on the civil rights movement, or the history of education in America. The lesson could also be used to enhance the study of African-American history.

Time period: 1960s

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School: From Freedom of Choice to Integration

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

-

Standard 4A- The student understands the "Second Reconstruction" and its advancement of civil rights.

Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

- Standard 2D- The student understands contemporary American culture.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School: From Freedom of Choice to Integration

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

- Standard A - The student compares similarities and differences in the ways groups, societies, and cultures meet human needs and concerns.

- Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

- Standard D - The student explains why individuals and groups respond differently to their physical and social environments and/or changes to them on the basis of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs.

- Standard E - The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

- Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding that different scholars may describes the same event or situation in different ways but must provide reasons or evidence for their views.

- Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

- Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

- Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

- Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculate scale, and distinguish's other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

- Standard A. The student relates personal changes to social, cultural, and historical contexts.

- Standard B - The student describes personal connections to places associated with community, nation, and world.

- Standard E - The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals daily lives.

- Standard F - The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

- Standard G - The student identifies and interprets examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.

- Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

- Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

- Standard B - The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

- Standard C - The student describes the various forms institutions take and the interactions of people with institutions.

- Standard D - The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group or institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

- Standard E - The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

- Standard F - The student describes the role of institutions in furthering both continuity and change.

- Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

- Standard H - The student explains and applies concepts such as power, role, status, justice and influence to the examination of persistent issues and social problems.

- Standard I - The student gives examples ans explains how government attempts to acheive their stated ideals at home and abroad.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

- Standard A - The student examines issues involving the rights, roles and status of the individual in relation to the general welfare.

- Standard B - The student describes the purpose of the government and how it's powers are acquired.

- Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

- Standard E - The student identifies and describes the basic features of the political system of the United States, and identify representative leaders.

- Standard H - The student explains and applies concepts such as power, role, status, justice, and influence to the examnation of persitent issues and social problems.

Theme IX: Global Connections

- Standard F -The student demonstrate understanding of concerns, standards, issues, and conflicts related to universal human rights.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

- Standard A - The student examine the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law.

- Standard B - The student identifies and interprets sources and examples of the rights and responsibilities of citizens.

- Standard C - The student locate, access, analyze, organize, and apply information about selected public issues recognizing and explaining multiple points of view. Standard D - The student practice forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

- Standard E - The student explain and analyze various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

- Standard F - The student identifies and explain the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

- Standard G - The student analyze the influence of diverse forms of public opinion on the development of public policy and decision-making.

- Standard H - The student analyze the effectiveness of selected public policies and citizen behaviors in realizing the stated ideals of a democratic republican form of government.

- Standard I - The student explain the relationship between policy statements and action plans used to address issues of public concern.

- Standard J - The student examine strategies designed to strengthen the "common good," which consider a range of options for citizen action.

Objectives for students

1) To examine how Green v. New Kent County challenged earlier Supreme Court decisions by placing an affirmative duty on school boards to integrate schools;

2) To describe the significance of the Green v. New Kent County Supreme Court decision in the fight for educational equality for minorities;

3) To understand the role of activism at the local level and how it relates to sweeping changes on a larger scale;

4) To research the history of segregation in their own communities and compare that to what occurred in the New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

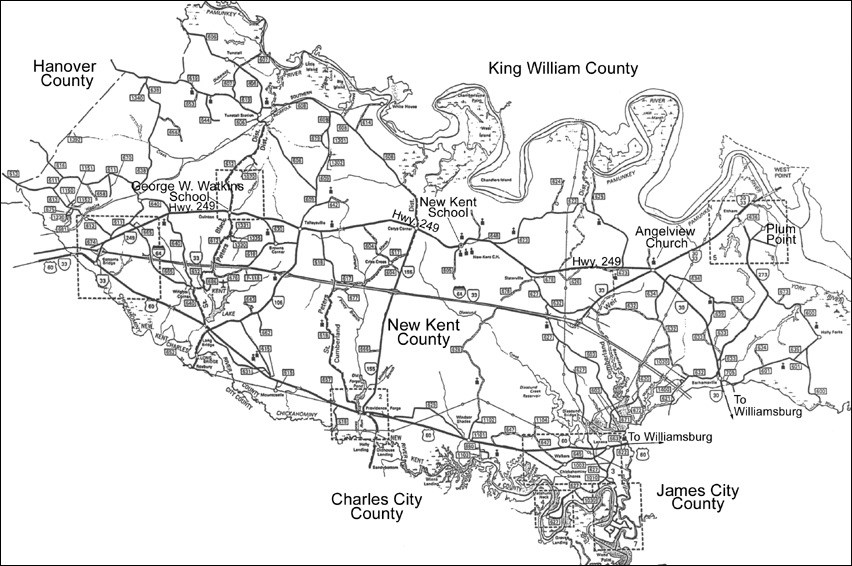

1) One map showing New Kent County;

2) Three readings on the history of the Green case, excerpts from the Green case, and oral histories from individuals involved in integrating New Kent County public schools;

3) Five photographs of students attending both New Kent School and George W. Watkins School.

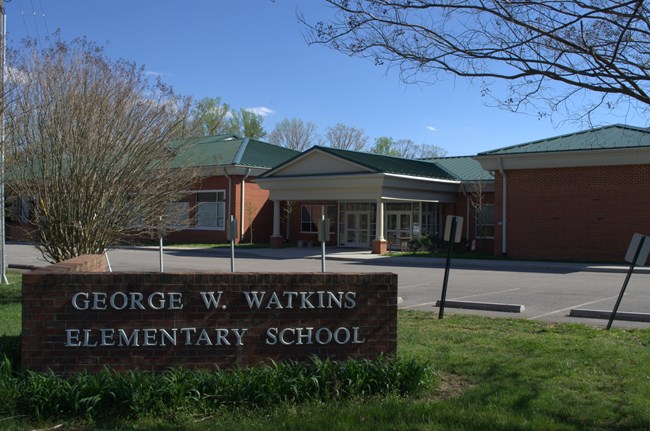

Visiting the site

New Kent County lies approximately 30 minutes east of Richmond, the capital of Virginia. Take Interstate 64 from Richmond and Exit 214 to Route 155. Route 155 North (left) from Interstate 64 leads into New Kent County. After approximately 4 miles, Route 155 intersects Route 249, the principal east-west route through the county. Follow Route 249 East (right) to the New Kent School (now a building of the Rappahannock Community College, 11825 New Kent Highway) on the right. Follow Route 249 West (left) for approximately 6 miles to the George W. Watkins School (now George W. Watkins Elementary School, 6501 New Kent Highway) on the left.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

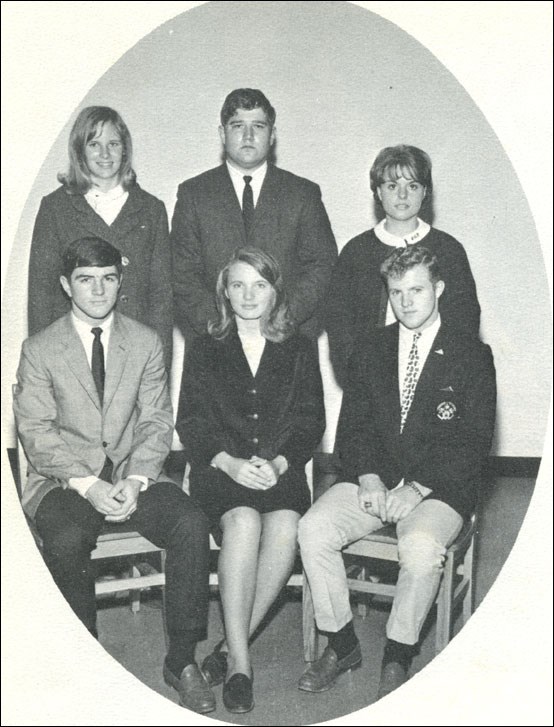

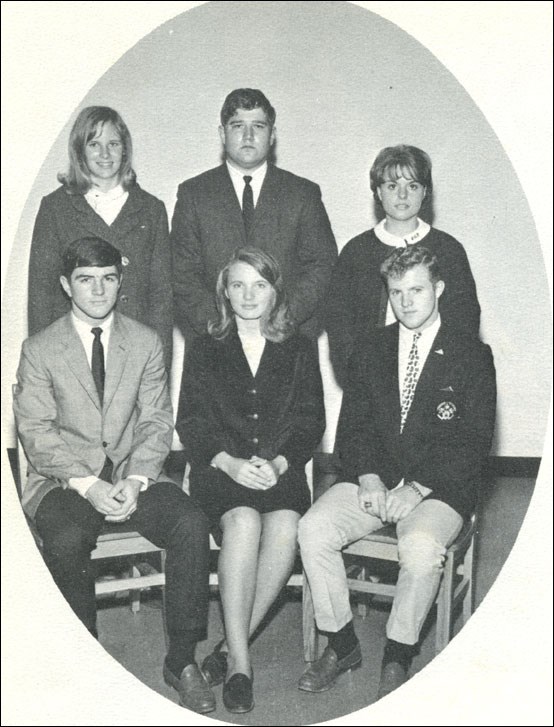

1967 New Kent School Yearbook. Courtesy of New Kent County Public Schools, Virginia.

1970 New Kent High School Yearbook. Courtesy of New Kent County Public Schools, Virginia.

These pictures were taken in 1967 and 1970, respectively. Both represent elected student government officers for New Kent School (by 1970, the school was renamed New Kent High School).

What do you think might have happened in the intervening years to encourage the election of a multiracial governing body at the New Kent School?

Setting the Stage

The issue of school desegregation was neither peculiar to the South nor to the 20th century. As early as 1849, in the school desegregation case of Roberts v. the City of Boston, attorney Charles Sumner, arguing on behalf of the African-American plaintiffs, stated:

Who can say that this does not injure the blacks? Theirs, in its estate, is an unhappy lot. Shut out by a still lingering prejudice from many social advantages, a despised class, they feel this proscription for the Public Schools as a peculiar brand. Beyond this, it deprives them of those healthful animating influences which would come from a participation in the studies of their white brethren. It adds to their discouragements. It widens their separation from the rest of the community, and postpones the great day of reconciliation which is sure to come.¹

Sumner's argument did not sway the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts in 1849. Massachusetts, however, did outlaw school segregation in 1855 after black and white abolitionists organized a propaganda campaign to persuade the Massachusetts legislature to enact a law prohibiting school segregation.²

The Massachusetts model did not become the basis of race relations in this country. Instead, after the Civil War and Reconstruction, a Louisiana case set the standard. In 1892, Homer Plessy refused to sit in the railroad car designated for blacks. By refusing to move, Plessy violated an 1890 Louisiana law, which provided for equal but separate accommodations for the white and "colored" races on state railroads. Plessy, tried and convicted at the local level, took his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1896, the Court determined in Plessy v. Ferguson that laws separating the races did not imply that one race was inferior to another. The Court concluded that if blacks felt inferior it was "...solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it."³

Fifty-eight years passed before Plessy was overturned in arguably the most well-known school desegregation case of all, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. In 1954, almost one hundred years after the legal desegregation of the Massachusetts schools, the Supreme Court struck down Plessy by declaring that separate schools were inherently unequal. Attorney Thurgood Marshall, like Sumner, argued that it was the intangible benefits that made the difference between segregated and desegregated schools. Marshall concluded that the mere fact of segregation sanctioned by law implied the inferiority of African Americans and prohibited children from the opportunity to "...learn to live, work and cooperate with children representative of approximately 90% of the population of the society in which they live; to develop citizenship skills; and to adjust themselves personally and socially in a setting comprising a cross-section of the dominant population."4

Unlike Sumner, Marshall succeeded in convincing the Court. A year later in Brown II, the second part of the decision relating to Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the court attempted to define the process by which desegregation would take place by directing federal district courts to enforce the desegregation of schools "with all deliberate speed." This left the door open for those in opposition to school desegregation to delay the process almost indefinitely.

Ten years later most southern schools, including the New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School, remained segregated. While African-American schools, such as the George W. Watkins School, could boast of a faculty that genuinely cared about its students, they still suffered from inadequate resources. It was at this time that Dr. Calvin C. Green, president of the New Kent County branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and father of three, decided it was time to take on the local school board in hopes of forcing the county to provide better educational opportunities for all students.

² Susan Cianci Salvatore, Waldo Martin, Vicki Ruiz, Patricia Sullivan, and Harvard Sitkoff, Racial Desegregation in Public Education in the United States Theme Study (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2000), 8.

³ Eric Foner and John A. Garraty, The Readers Companion to American History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1991), 844.

4 Mark V. Tushnet, ed., Thurgood Marshall: His Speeches, Writings, Arguments, Opinions, and Reminiscences (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2001), 22.

Locating the Site

Map 1: New Kent County Map.

Adapted from the General Highway Map for Charles City and New Kent Counties. Courtesy of the Virginia Department of Transportation, Office of Public Affairs.

Questions for Map 1

1) Using a school atlas, locate New Kent County on a state map of Virginia.

2) Using Map 1, locate the New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School. They are approximately 7 to 8 miles apart.

3) Locate the area of Plum Point and the community surrounding Angelview Church, two communities known for being predominantly black in the 1960s. What route would students that lived in the eastern end of New Kent County travel to attend the all-black George W. Watkins School?

4) What school did the black students pass on the east-west route to attend George W. Watkins? How do you think passing this school affected their outlook and their education?

5) In the 1960s, New Kent County's population was 52% white and 48% black. How do you think this may have affected both the white and black citizens' attitude/outlook on school desegregation and the civil rights movement in general?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: History of Charles C. Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, VA

In the mid-1950s, life in New Kent County was divided by a "color line." Blacks and whites were born in separate hospitals, raised and educated in separate schools, and buried in separate cemeteries. Such separation had been legalized by the U.S. Supreme Court's Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896, but only if facilities for the two races were equal.

During the 1940s, the Virginia State Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the state headquarters of the nation's premier civil rights organization, filed numerous lawsuits to force Virginia to "equalize" the public facilities used by blacks and whites. These suits were generally successful, however, the rulings applied specifically to the districts involved instead of addressing the overall problem. In the 1950s, NAACP lawyers switched tactics and began attacking segregation outright, arguing that separation of the races was itself unconstitutional. In 1954, this new legal strategy led to the consolidation of five cases under one name, Oliver Brown et al. v. the Board of Education of Topeka. One of the five cases came from Virginia: Davis v. Prince Edward County, Virginia (1952). The Brown decision by the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation in public schools, because separate schools could never be truly equal, was unconstitutional.

Following this historic ruling, most southern states sought to delay school integration. Virginia, in particular, resisted in several ways. Virginia legislators chose to pass a "resolution of interposition" in early 1956. This resolution declared that the Supreme Court's decision to integrate schools was incompatible with the state constitution and therefore inapplicable in Virginia. Virginia also led a "Massive Resistance" movement among southern political leaders, during which several Virginia localities closed their public schools rather than integrate them. During one such instance in Prince Edward County, white students attended private schools while many African American students moved elsewhere to attend school or did not attend school at all. For years, black parents fought through the courts to reopen the schools on an integrated basis. In Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1964), the Supreme Court ordered the county to reopen its schools on an integrated basis and to desist from operating a whites-only private school system.

In the small, rural, eastern Virginia county of New Kent, ten years after Brown, blacks and whites continued to attend separate schools: the all-black George W. Watkins and the all-white New Kent. Moreover, blacks in New Kent County were well aware that their school, controlled and funded by an all-white school board and all-white county politicians, was inferior in a variety of ways. The black school lacked a gymnasium and sports fields, and textbooks and school equipment were inferior.

Calvin C. Green and his wife moved to New Kent County in 1956 from nearby Middlesex County. Almost immediately, Dr. Green became active in the local branch of the NAACP, becoming president of the local branch in 1960. Partly because of his three school-age sons, Green pressured the local school board to comply with the Brown decision in the early 1960s, to no avail. Then in 1964, at a meeting in Richmond, Green heard attorneys from the State Conference of the NAACP explain that the recently passed Civil Rights Act of 1964 threatened to cut off federal funding to localities which refused to develop a plan to integrate their schools. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 laid the groundwork for greater federal enforcement of school desegregation. Title VI of the Act forbade racial discrimination in any program receiving federal funds. This was a powerful new weapon for the NAACP, and the association sought to use it in Virginia (and other southern states) to bring about the integration of public schools. First, NAACP lawyers needed determined and courageous individuals to sponsor lawsuits against their local school boards. Calvin C. Green, among others, volunteered.

Green returned to New Kent County and started a petition drive among black residents. The petition urged the New Kent School Board to integrate the schools as quickly as possible. Within a short time, Green obtained the signatures of 540 local black residents and submitted the petition to the school board. The board refused to comply.

In response to the board's refusal, Green began meeting with attorneys from the state NAACP and in early 1965 helped develop a lawsuit to force the New Kent School Board to integrate the county's schools. Charles C. Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia in March 1965. The suit was filed in Calvin Green's youngest son's name because he had the most years ahead of him as a student in the county and was most likely to still be in school if the case took a long time.

The lawsuit was organized and argued almost entirely by the lawyers of the state NAACP. Several of Virginia's pre-eminent civil rights attorneys, including Samuel W. Tucker, Henry L. Marsh III, and Oliver White Hill participated in the process. The U.S. District Court ruled against them in 1966, as did the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals. Both courts ruled that a hastily developed plan, issued in August 1965 by the New Kent School Board, satisfied the requirement that it begin integrating the county's schools. Facing the lawsuit filed by Green and the possible loss of federal funds from the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the school board had fashioned a new strategy to address segregation. This plan, known as a "freedom-of-choice" plan, required that black students and their parents petition for admittance to the white schools in order to attend. Such a process invited the possibility of economic and physical reprisals from whites that opposed desegregation. As a result, the "freedom-of-choice" plan did not significantly alter the racial composition of the county's two public schools.

After their loss in the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, the NAACP chose to take the Green case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In October 1967, NAACP attorneys argued that the county school board's "freedom-of-choice" plan illegally placed the burden of integrating the county's schools on blacks themselves. They also argued that the county sought to maintain a biracial school system by busing some black students up to 20 miles to the all-black George W. Watkins School, though the predominantly white New Kent School was much closer.

In May 1968, more than 14 years after the original Brown decision, the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Charles C. Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia. The Court found that the county had been operating a dual system of schools as ruled unconstitutional in Brown, down to "every facet of school operations--faculty, staff, transportation, extracurricular activities and facilities."¹ Its 1954-55 desegregation decisions put an "affirmative duty" on school boards to abolish dual schools and to establish "unitary" systems. It disapproved the county's "freedom-of-choice" school plan for this case. Justice William J. Brennan, writing for the Court, explained: "The burden on a school board today is to come forward with a plan that promises realistically to work, and promises realistically to work now." The Court ordered the local school board to develop a new plan to "convert promptly to a system without a 'white' school and a 'Negro' school, but just schools." It also ordered that the U.S. District Court maintain oversight of the case and the school board's plan to ensure that integration would occur in the near future. Shortly thereafter, the New Kent School Board converted the George W. Watkins School into New Kent Elementary School and shifted all the county's high school students to the formerly all-white New Kent School making it New Kent High School. Green and the NAACP had won a very important victory.

Supreme Court Justice William H. Rehnquist later referred to the Green case (in 1972) as a "drastic extension of Brown."² The case, though based in New Kent County, affected school systems throughout the nation. It was in Green v. County School Board that the U.S. Supreme Court announced the duty of school boards to affirmatively eliminate all vestiges of state-imposed segregation, thus extending Brown's prohibition of segregation into a requirement of integration. Within only a few years, the nation witnessed the culmination of a key phase of the early civil rights movement--the integration of the nation's public schools.

Questions for Reading 1

1) Why do you think so many southern whites fought against school desegregation in the 1950s and 1960s? Why were many of the local blacks equally determined to integrate the county's schools?

2) List three cases important to the school desegregation decisions decided by the Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s and describe their significance. What were the results of each case?

3) What is the NAACP? What role did the organization play in the Green case?

4) What was the "freedom-of-choice" plan and why did the New Kent School Board implement this plan? Do you think the name of the plan accurately described how it worked in practice? Why or why not?

5) Why was the Brown decision not strong enough to fully integrate schools? What did the Green decision do that the earlier cases did not?

¹ Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), at 435.

² Justice William H. Rehnquist in Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413 U.S. 189 (1972).

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Excerpts from the Supreme Court Decision Green v. County School Board of New Kent County (1968)

--"During the [New Kent County 'freedom-of-choice'] plan's three years of operation [started August 2, 1965] no white student has chosen to attend the all-Negro school, and although 115 Negro pupils enrolled in the formerly all-white school, 85% of the Negro students in the system still attend the all-Negro school."

--"Racial identification of the system's schools was complete, extending not just to the composition of student bodies at the two schools but to every facet of school operations--faculty, staff, transportation, extracurricular activities and facilities. In short, the State, acting through the local school board and school officials, organized and operated a dual system, part 'white' and part 'Negro.'"

--"... what is involved here is the question whether the Board has achieved the 'racially nondiscriminatory school system' Brown II held must be effectuated in order to remedy the established unconstitutional deficiencies of its segregated system."

--"In determining whether respondent School Board met that command by adopting its 'freedom-of-choice' plan, it is relevant that this first step did not come until some 11 years after Brown I was decided and 10 years after Brown II directed the making of a 'prompt and reasonable start.' Such delays are no longer tolerable..."

--"Moreover, a plan that at this late date fails to provide meaningful assurance of prompt and effective disestablishment of a dual system is also intolerable."

--"... the District Court approved the 'freedom-of-choice' plan.... The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ... affirmed the District Court's approval of the 'freedom-of-choice' provisions of the plan but remanded the case to the District Court for entry of an order regarding faculty 'which is much more specific and more comprehensive' ..."

--"The New Kent School Board's 'freedom-of-choice' plan cannot be accepted as a sufficient step to 'effectuate a transition' to a unitary system...no whites have gone to George W. Watkins school and 85% of blacks remain at George W. Watkins school.... In other words, the school system remains a dual system. Rather than further the dismantling of the dual system, the plan has operated simply to burden children and their parents with a responsibility which Brown II placed squarely on the School Board."

--"We do not hold that a 'freedom-of-choice' plan might of itself be unconstitutional, although that argument has been urged upon us."

--"Where a 'freedom-of-choice' plan offers real promise of achieving a unitary, nonracial system there might be no objection to allowing it to prove itself in operation, but where there are reasonably available other ways, such as zoning, promising speedier and more effective conversion to a unitary school system, 'freedom of choice' is not acceptable."

--"... it is evident that here the Board, by separately busing Negro children across the entire county to the 'Negro' school, and the white children to the 'white' school, is deliberately maintaining a segregated system which would vanish with non-racial geographical zoning."

--"The Board must be required to formulate a new plan and, in light of other courses which appear open to the Board, such as zoning, fashion steps which promise realistically to convert promptly to a system without a 'white' school and a 'Negro' school, but just schools."

--"Moreover, whatever plan is adopted will require evaluation in practice, and the court should retain jurisdiction until it is clear that state-imposed segregation has been completely removed."

Questions for Reading 2

1) Under the "freedom-of-choice" plan, what percentage of white students chose to attend the George W. Watkins School?

2) What does the term "dual system" mean?

3) Why did the Supreme Court rule against New Kent County and force it to desegregate its schools immediately?

4) How many years after Brown II did the Green decision take place? Why is that significant? What do you think is the overall historical significance of the Green decision?

5) Why would the federal courts want, or need, to retain jurisdiction over New Kent County's next plan for integration?

Reading 2 was excerpted from Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Perspectives on the New Kent County Experience

Dr. Calvin Green, founding president of the New Kent County Chapter of the NAACP, sued the New Kent County School Board. Jody Allen conducted this interview on November 2, 2001 at Dr. Green's home in New Kent County.

Topic: Dr. Green on the impact of Brown

Now, '54 we were informed of Brown and it was an exciting year all over the United States and it gave us a brand new talking thing and a brand new big effort, and that was the year my wife finished college--Virginia State College in '54. The NAACP was smart enough to realize that nothing was happening by that definition in '54 all it did was declare segregation to be unconstitutional. So they went back to court in '55 with Brown II. The effort there was to try to do more than have it declared unconstitutional because we'd been sitting like Plessy v. Ferguson for all those years getting nothing done and they wanted the country to order some movement toward getting rid of it. OK, and so the Supreme Court ordered in '55 in Brown II that segregation needed to be dismantled with all deliberate speed. Eisenhower was the president and when people got all upset and put pressure on the politics, Eisenhower made his famous remarks about taking it slow, that deliberate speed was the language but it meant take it slow and not upset the country. So with his language of moving slowly it actually put brakes on all four wheels of Brown and so nothing happened with Brown. OK? If Eisenhower had not interjected the idea of taking it slow the courts, the lower courts, would have ruled some action. But he was a popular president and they accepted his idea of going slow and so then Brown became a talking word but it wasn't getting anything done.¹

Question: In the early 1960s, what was the NAACP trying to do to bring about school desegregation?

Nothing, because there was nothing to do. We were just living in the love of Brown. Everybody could walk around and say Brown, say it's illegal, but that was as far as it got. Nothing was happening throughout Virginia or the United States for all practical purposes in terms of integration.

Question: Did you ever have any regrets?

I was acquainted with the grief associated with being a civil rights leader. I was not seeking grief. I was seeking that somebody further down the road would have some better opportunities than we had.

[Dr. Green said, "segregation was a way of life" for so long that he didn't question it. An incident that occurred while he was in college opened his eyes. As a pre-med major at Virginia State College (VSC), Dr. Green, along with a group of students began pressuring the college to provide stats on how many alumni were accepted into medical school. In response, VSC threatened to suspend the students. Dr. Green responded by deciding to transfer.]

In Dr. Green's words:

I wrote to VPI (Virginia Polytechnic Institute) and requested a transfer to VPI. VPI wrote me back this nice little letter and told me I was at the school I was supposed to be at. I didn't really know what they were talking about. I'm serious. They said I was at the school I'm supposed to go to. They didn't tell me that I was black and couldn't come to VPI. They said I'm at the school I was supposed to be at. It was then when I did some studying to realize that Virginia State College at Petersburg was the only college [state school] for black people in this whole state. It was the only place for us to go; I didn't realize that Virginia State was the only place for me to be. I began to wake up and realize that there are some real things to deal with in this world.

Cynthia Lewis Gaines, former George W. Watkins student, one of the first students to integrate New Kent School, under "freedom of choice." This interview was conducted by Brian Daugherity and Jody Allen on November 13, 2001 in Mrs. Gaines' office at William Fox Model Elementary School in Richmond.

Topic: First day at New Kent School

Well, [sigh] the school, the inside of the school is a little bit different now than it was when I actually went there. When I went there, you came in the front door and there was an auditorium and a walkway all the way around that auditorium. It was customary that kids came in the building and stood all around that auditorium until the bell rang. Which meant that my first day there I had to walk through all the kids who were standing there staring at me. So, there was a little name-calling, a little laughing, all those kinds of things going on as we walked through. I felt strange walking in because it was all new, but I wasn't afraid to walk in there.

Question: What other types of experiences did you have at New Kent School that first year?

Well, I remember being in classes and I always tried to sit on the first row or second row, and I would just be in class and I'd go like this [runs her hand through her hair] and the back of my head was just full of spit balls that the kids behind me were blowing in my head. They would chew the paper up real tiny and blow it through the little Bic ink pens, so you wouldn't really feel it, but when you stuck your hand in your head you felt it.

When we first got there, if we came out of the cafeteria line and sat at a table the entire table would get up. So, after about two days of that I said, "you know what? We are going to the cafeteria today and everybody's going to sit at a different table and we are going to clear 11 tables" (there were 11 black high school students that year). They [her friends] were like all right, let's do it. So we go in, each one comes out of line and we sit at a different table. We cleared 11 tables, kids standing all around the walls with their trays in their hands just eating and we're just laughing because after a while we had to make it funny. If we didn't make it funny, we couldn't have made it [pounds hand on table with each word]. So we just found ways to make it funny.

At the high school, there was really no attempt by the students or teachers to make us fit in, so we were charged with making ourselves fit in. So I'll give you an example: the first year I was there I tried out for the girls basketball team, and I was the first black girl to ever play basketball for New Kent. But at that time the varsity team, the cheerleaders, and the girls team all rode on the same bus because we didn't have JV (Junior Varsity) girls way back then. But no one would sit by me on the bus the entire basketball season; I don't care if we went to Matthews, Middlesex, Yorktown, for miles no one would sit by me on the bus. And they would sometimes sit three in a seat to keep from sitting by me on the bus, so after a while you just had to make things funny so you wouldn't be hurt. So I would cross my legs, stretch out on the seat put my suitcase up, and prop my feet up and just ride.

And there were girls on the team that did not mind passing me the ball because they knew I could play, so I would pass them the ball. If I got out there and it was somebody who had been mean to me, and I mean I was a child, I know that's not right now, but.... [laughter] I wouldn't pass them the ball. I didn't care if we missed the basket or the points, I wouldn't do it.

And I remember my first basketball game. My parents could not attend and they said "but you go ahead. You'll be all right because it's at a school." Actually it was a private school, and it was a Catholic school, so you're going to be all right. I went to that game and I was the only black person in the gym. And I saw the janitor come by and look in there because he, I guess, wondered where I came from. When they did the starting line up, 'cause I was in the starting line up, and back then there were six girls on the team, just like guys had six, and so they did the starting line up, and I was the last person they called. This man who was up there in the stands, he stood up--and you know how it's quiet because you've just done the Star-Spangled Banner and then they introduce the team--so it's kind of quiet and they had clapped and then they called my name. And this parent stood up and said, "Oh my God, five white girls and one African," and the entire gym just broke into laughter and there I was on the floor in the eighth grade.

Question: What were your classes like?

I won't say that the courses were more challenging because we had good teachers at the black school. Their [New Kent School] tests; there were more items. Like the first test I had in eighth grade in my world geography test, or whatever it was, had 150 questions on it, which was something I had not seen. But now, that could have just been the difference between seventh and eighth grade. I don't know what the kids in eighth grade would have had at Watkins (George W. Watkins School).

Question: How did the schools compare?

We actually had more courses [New Kent School]. For example, we had Latin, we had Spanish, and we had French. Well, see, the black school had one language. The science class at the black school only had three microscopes, but yet, at the white school there was a microscope for two children to sit and share. But we only had three and we only had two sinks in that science class. We also had used textbooks. The furniture was not as nice. We had good teachers and good people [at George W. Watkins].

Question: Were there any white teachers who interacted favorably with you?

Sure. Mr. Galloway, Mr. Chapman, Rev. Stansfield, Mrs. Thomas

Question: Did you ever become friends with any of the white students?

Once they got to know us. By my sophomore year, we actually had friends, black and white friends.

Question: How did the community respond to the lawsuit?

There was opposition also from blacks as well as from whites. There were parents and kids who thought we shouldn't go down there. There were teachers at the school who thought we shouldn't go there. There were teachers and students who were very angry with us because in the end, they lost their school.

Howard Ormond was one of the first black teachers transferred to New Kent School in 1967. This interview was conducted on October 30, 2002 by Sarah Trembanis and Brian Daugherity at Mr. Ormond's Office at the New Kent Middle School (formerly the New Kent School).

Topic: Teacher preparation for desegregation

We went through training. The University of Virginia provided us with consultants who came down every week and we worked on it. They would come up with some pretty good hair raising questions or topics to make you think, make you be sensitive to a black child or a white child. They put stuff on the table to see if your hair would curl up on your head.

We all got along because we were all adults so we had a pretty good relationship as far as a staff was concerned. So we didn't have a problem as far as dealing with the kids and they [students] saw us [teachers] getting along. I guess they said, "well this is going to be OK."

Topic: Physical Education and athletic opportunities at George W. Watkins

They [George W. Watkins students] did not have any teams other than baseball. They were the champion baseball team. The kids never had seen a basketball game. They never had played basketball. They never had physical education. They had recreation, recess... they'd never had a music department. So when I came--and this was in '67--when I came, the music teacher, Mr. Harold Davis, started a band and he started...majorettes. I started the first basketball team that these kids had ever played. At the time New Kent was in the same division as Charles City [a neighboring county]. We did not have a gym, they did not have basketball goals, didn't have anything. So the kids didn't know anything about basketball. So I asked the principal, I said, "well, since we have a two division school system, can you ask Charles City if we can come over there to practice to start a team," and he was kind of reluctant because he thought that was too hard to do. I said, "no it's not." [There were] kids that had outstanding size and ability. They won the state AA, they used to have an AA league which was the black league, they won that in baseball every year. They were just that good but they never knew anything about football and basketball.

So I started the first basketball team. I had 12 kids; they didn't know how to do a lay up, they didn't know how to do a jump shot, they didn't even know how to play defense and offense. So what I did, we would have to go to Charles City and practice after their team practiced. So we had a student who drove the bus. We drove from New Kent, G. W. (George W.) Watkins School all the way over to Charles City, which is Ruthville.

Question: How far was that?

Uh, that's about between 15 to 18 miles I guess, to practice. So, we couldn't practice until after 8:00 p.m. because their team would practice first and then we would practice after that, and then drive the kids all the way back to New Kent and drop them off along the way at their spots. So, we started a basketball team. So that first year we played and we competed against different teams, and the kids had a love for basketball. So, that's the first of basketball. We never did have a football team.

Question: How did the white high school compare in terms of facilities?

They had all the teams, and they had a gym. See, G. W. (George W.) Watkins didn't have a gym. And they had a football field, and they had a baseball field and coaches. [laughs] They had everything that you would have, that you would expect that the black school should have had, that they did not have.

The only thing that the black school had...was a baseball team. Where we played baseball teams and where we practiced baseball was in a black parent's field for the community team...which was two blocks from the school. The school did not have a field at the school site to play softball.... The Dixon family had a field behind their house because their sons liked to play baseball,... and that's where we played.

Question: Did the community feel that the lawsuit was forced on it by outsiders?

No, the reason for that was Dr. Green. See, he was an insider, he was the focal point. He was doing it for the good of the kids, for the parents who had probably approached him, and also because of the law. So, by him being a member of the community, it wasn't like they're forcing us from outside per se.

Senator Henry L. Marsh, III was the primary liaison between the New Kent NAACP and the NAACP's State Conference attorneys who argued the suit. He was involved in the legal preparation of the case. This interview was conducted by Brian Daugherity and Jody Allen on November 25, 2002 in Senator Marsh's office in the General Assembly Building in Richmond.

Topic: On choosing New Kent

We had all these school cases, and we wanted to get a case to be the pilot case so the Supreme Court could really break the log jam. Charles City had 87% black population, and we had thought that Charles City would be the lead case, but then it dawned on us that Charles City was so atypical that a decision in Charles City wouldn't help us because there was no other jurisdiction, or very few with 80% African Americans, so a decision from that case really wouldn't help us too much.

So the neighboring county was New Kent, and it was simple because it had 2 schools...The population [black and white] was about equal. It was a logical solution. We had strong plaintiffs in New Kent. Green, the president of the NAACP, was a strong leader. That's important--to have a case with a strong leader, so the people won't back out on you, and they won't be intimidated. So New Kent was the logical choice.

Topic: The importance of Green

At that time HEW, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, was following the law, so as long as courts were saying that "freedom of choice" was O.K., we weren't getting much desegregation even though the government had put many, many resources into desegregation. When the Supreme Court said that "freedom of choice" was not the answer and [it was understood] that the Supreme Court meant now; "all deliberate speed" meant now [pounds fist on desk for emphasis]; "you need to desegregate now" in capital letters. That meant that "freedom of choice" could no longer be a defense. So then HEW, Office of Civil Rights took that precedent and implemented that across the country.

That's when we had real meaningful desegregation--all over in 1968. Before we had the decision, desegregation was stymied because you only had desegregation where you had black applicants willing to run the gauntlet in white schools. After Green v. New Kent as long as "freedom of choice" was not working, it was unlawful. So HEW took that decision and implemented desegregation on a wide basis--before that decision it didn't happen so that was a crucial case.

Questions for Reading 3

1) What do you think Dr. Green meant by "living in the love of Brown?" Why was Brown II ineffective at forcing school desegregation?

2) Why did Dr. Green take on being the lead in this case? When did he first realize that the system of "separate but equal" was not right?

3) According to Cynthia Gaines, what techniques were used to isolate the African-American students? What techniques did African-American students use to cope with isolation at New Kent School? Do you think you could have survived in a similar situation?

4) According to Ms. Gaines, there was some opposition to the lawsuit from the black community. What do you think might have been the reason for that?

5) Based on the interviews with Ms. Gaines and Howard Ormond, who seemed to adjust more easily to integration--the students or the teachers? Why do you think that was the case? What made the difference in both of their experiences for getting along with their peers?

6) According to Senator Henry Marsh, why was New Kent County chosen as the lead case?

7) According to Senator Marsh, what role did the HEW play in slowing down the process of desegregation? What did HEW do after the Green decision?

8) List the differences noted in the given perspectives between George W. Watkins and New Kent School. How were blacks being deprived of an adequate education because New Kent County maintained segregated schools?

9) Who were the people involved in integrating the New Kent County public school system? What were their roles? What does this tell you about the role that local activism plays in changing society?

10) Do the oral histories presented in this reading help you better understand the experiences of the individuals involved in the fight for educational equality? Why is it important to preserve the stories of these individuals? Do you think studying oral histories is an effective way to learn about historic events? Why or why not?

¹ By the time the Brown decision was handed down in 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower was already known as a moderate and so it could be argued that his response to the landmark school desegregation ruling was in keeping with his established mode of operation. Eisenhower believed it problematic to express his feelings regarding any Supreme Court decision. He did send a message to the 54th annual meeting of the NAACP in which he said, "We must have patience without compromise of principle. We must have understanding without disregard for differences of opinion which actually exist. We must have continued social progress, calmly but persistently made..." This did not satisfy the NAACP and others who called for immediate implementation of the ruling. James C. Duram, A Moderate Among Extremists: Dwight D. Eisenhower and the School Desegregation Crisis (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1981), 111.

Visual Evidence

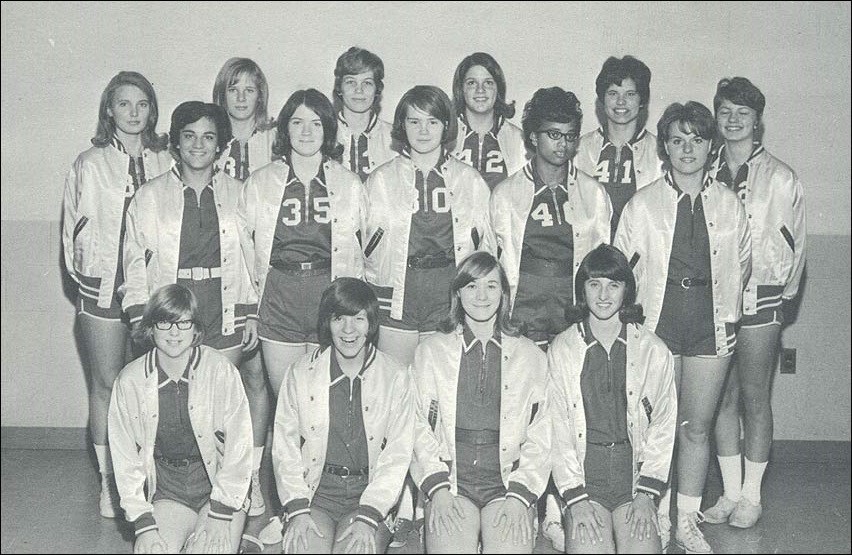

Photo 1: 1967 New Kent School girls' basketball team.

1967 New Kent School Yearbook. Courtesy of New Kent County Public Schools, Virginia.

Photo 2: 1967 New Kent School student government officers.

1967 New Kent School Yearbook. Courtesy of New Kent County Public Schools, Virginia.

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1) Based on what you learned in Reading 1, what desegregation plan was in effect when these pictures were taken?

2) Note the sole African American player, Cynthia Gaines, in Photo 1. How do you think it felt to be the only African American player on the team?

3) Cynthia Gaines would not have been able to play basketball at George W. Watkins--they did not have a basketball team. How did the athletic opportunities differ between New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School? If needed, refer to Reading 3.

4) In Reading 3, Mrs. Gaines recounts a story about the first time she traveled to an away game. What happened to her at that game? How do you think she felt? Could that happen today? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence

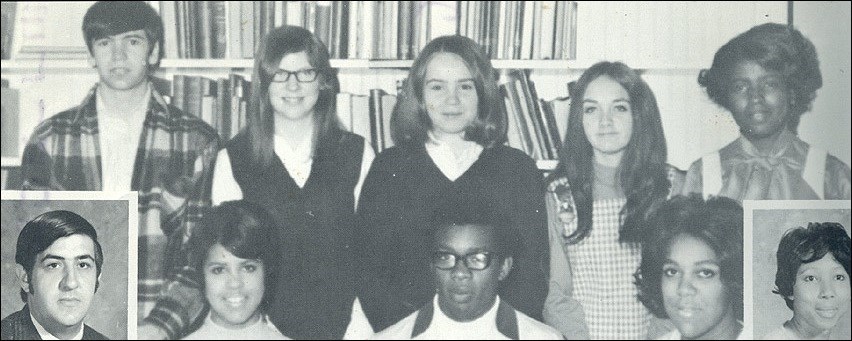

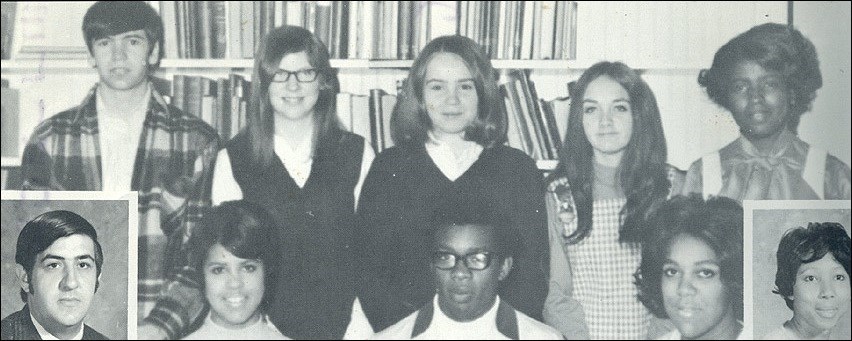

Photo 3: 1969 George W. Watkins junior class.

1969 George W. Watkins School Yearbook. Courtesy of New Kent County Public Schools, Virginia.

Photo 3 was taken after the Green decision and before combining the two schools as one high school.

When the Green decision was made in 1968, three years after the "freedom-of-choice" plan was issued in New Kent County, no whites attended George W. Watkins and 155 blacks attended New Kent School. That left 85% of the blacks in the system at George W. Watkins.

Questions for Photo 3

1) Considering the information provided in the caption above, do you think the student government officers in Photo 2 represented all races attending New Kent School? Explain your answer.

2) Under "freedom of choice" the students in Photo 3 could have petitioned to attend New Kent School. Why do you think they chose to stay at George W. Watkins?

3) Why do you think there were no white students in Photo 3?

4) What do you think the advantages and disadvantages of staying at the George W. Watkins School might have been under the "freedom-of-choice" plan? Refer to Reading 1 and Reading 3.

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: 1970 New Kent High School student government officers.

1970 New Kent High School Yearbook. Courtesy of New Kent County Public Schools, Virginia.

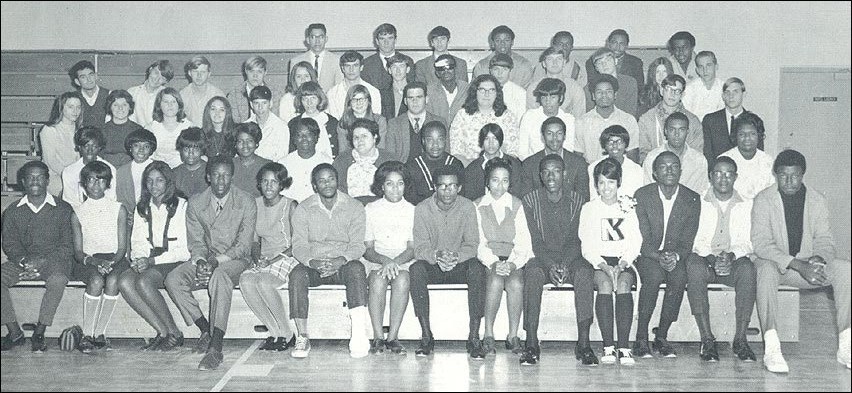

Photo 5: 1970 New Kent High School senior class.

1970 New Kent High School Yearbook. Courtesy of New Kent County Public Schools, Virginia.

Questions for Photos 4 & 5

1) Compare Photo 4 and Photo 5. Do the student government officers in Photo 4 represent demographically the students attending New Kent?

2) What do these images tell you about the demographics of New Kent County at this time? If needed, refer to Reading 1.

Putting It All Together

The experiences of the New Kent County schools are emblematic of many other schools in the South during the 1950s and 1960s. The following activities are designed to help students understand some of the personal stories of those individuals that experienced segregation and desegregation in the U.S. and the history of their own local schools and communities in relation to the movement to end segregation.

Activity 1: Oral Interviews--Preserving a piece of history

Unlike earlier time periods in history, we are fortunate enough to have many people alive and well with vivid memories of the 1950s and 1960s. Have students conduct oral interviews of community or family members who remember the segregation debates from the 1960s. As a class, decide what questions you would like to have answered. If needed, have students refer to the readings for guidance as well as any relevant textbook materials. Have students document their accounts and offer them to the local library or historical society to preserve the history for future generations.

Activity 2: History of My School

Segregation was largely a national problem; communities across the U.S. were affected by the civil rights movement and the fight over desegregation. At the same time, local, regional, and state factors greatly influenced communities' experiences with desegregation.

If possible, have students use newspapers, yearbooks, and other primary materials to construct a history of their school or a school in their community from 1954-1970 (essentially from the Brown decision through the implementation of the Green decision). Students should then write a paper comparing the situation in their community and school with the situation in New Kent County, Virginia. Was the school segregated or integrated during this time period? How was the situation similar or dissimilar to that in New Kent County? What local, regional, or state factors might contribute to these similarities or differences? What, if any, physical differences existed between local schools and the New Kent schools, and what if any significance do those differences have in the history of segregation and desegregation?

Activity 3: First person account

Historians often use journals and diaries as primary sources in order to get firsthand accounts of historical events. These sources are always subject to the personal opinions and biases of their authors. Have students find and read an interview or personal narrative of someone who experienced segregation and/or desegregation in schools. Students should be able to find many excellent sources online through simple internet searches. Some sites include:

- Video interviews from the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative’s Somebody Had To Do It project

- Recollections in the NEA’s article, “I Remember That Day”

- Photographs and recollections in the University of Richmond Museums’ publication Growing Up in Civil Rights Richmond

Ask students to record what they think are the most important parts of their account. Did anything they read surprise them? Hold a classroom discussion about the accounts that students read and have students discuss the different perspectives in relation to desegregation.

New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School:

From Freedom of Choice to Integration--

Supplementary Resources

By studying New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School: From Freedom of Choice to Integration students learn about the U.S. Supreme Court case that forced the integration of public schools and meet the individuals that experienced segregation, fought to dismantle the institution, and integrated the public school system of New Kent County, Virginia. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

University of Virginia: Civil Rights in U.S. and Virginia History

This website from 2004 stems from a course at the University of Virginia that covers segregation and the Civil Rights Movement in a local and national context. The website offers a wealth of documents, images, and sources, including the Virginia Interposition Resolution of 1956, images from the Davis case, and much more.

Virginia Commonwealth University: Photographs of Black and White Schools, Prince Edward County, Virginia--1961-1963

These images, by Dr. Edward H. Peeples, of the schools in Prince Edward County illustrate the differences between the resources that the county provided for its black students compared to its white students. According to Peeples' research, in 1951 all but one of the 15 black school buildings were wooden frame structures with no indoor toilet facilities, and had either wood, coal, or kerosene stoves for heat (one additional brick school building was built for blacks in 1953).

National Park Service

Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park System. The site is located at Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. Monroe was the segregated school attended by the lead plaintiff's daughter, Linda Brown, when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in 1951. The park's Web page provides in-depth information on the case as well as related cases, and visitation and research information.

The National Register of Historic Places' on-line travel itinerary, We Shall Overcome: Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement provides information on many places (in states across the U.S.) listed in the National Register for their association with the modern civil rights movement, including both the George W. Watkins School and the New Kent School.

In 1998, Congress authorized the National Park Service to prepare a National Historic Landmarks Theme Study on the history of racial desegregation in public education. The purpose of the study is to identify historic places that best exemplify and illustrate the historical movement to provide for a racially nondiscriminatory education. This movement is defined and shaped by constitutional law that first authorized public school segregation and later authorized desegregation. Properties identified in this theme study are associated with events that both led to and followed these judicial decisions. Both the George W. Watkins School and the New Kent School were identified and later designated as National Historic Landmarks.

PBS

In this exclusive interview, Little Rock Nine member Melba Pattillo Beals describes her experience when integrating Central High.

Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute

The Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute is an educational partnership between Yale University and the New Haven Public Schools designed to strengthen teaching and learning in schools. The website features curricular resources produced by teachers participating in Institute seminars, including “From Plessy v. Ferguson to Brown v. Board of Education: The Supreme Court Rules on School Desegregation.”

The Brown Quarterly Newsletter for Classroom Teachers

The Brown Quarterly is a publication of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research which provides access to curricular resources available from national parks dealing with diverse historical issues such as school desegregation, assimilation of American Indians, Mexican American immigration, and much more.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress offers a collection of materials and essays on African-American history topics such as colonization and abolition.

Teach Civics with this Lesson

-

The Judicial System

The Judicial SystemHow does the judicial system work? What is a federal court? Why are people trying to reclassify certain offenses?

-

Federalism

FederalismWhat is federalism? How have some Americans used debates about federalism to promote segregation?

-

Teaching Engaged Citizenship

Teaching Engaged CitizenshipUse these mini-lessons to fit civics education into a variety of social studies classrooms.

Tags

- african american history

- civics

- civil rights

- shaping the political landscape

- art and education

- virginia

- virginia history

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- desegregation

- civil rights movement

- african american women

- education

- segregation

- desegregation of public education

- mid 20th century

- early 20th century

- early 20th century history

- progressive era

- civil rights history

- supreme court

- supreme court of the united states

- twhplp

- crbp aah