Last updated: May 12, 2020

Article

Maryland and the 19th Amendment

Women first organized and collectively fought for suffrage at the national level in July of 1848. Suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott convened a meeting of over 300 people in Seneca Falls, New York. In the following decades, women marched, protested, lobbied, and even went to jail. By the 1870s, women pressured Congress to vote on an amendment that would recognize their suffrage rights. This amendment was sometimes known as the Susan B. Anthony amendment and became the 19th Amendment.

The amendment reads:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex."

The First Suffragist?

Maryland can trace its activism for woman suffrage all the way back to its very earliest days as a British colony. In 1648, Margaret Brent, a lawyer and executor of Governor Leonard Calvert’s estate, petitioned the Maryland General Assembly for a vote in the governing body. She argued that as a landowner, she was due the same rights that male Marylanders enjoyed. The Assembly rejected her demand.

As in many southern states, there was no significant organizing for woman suffrage in Maryland before the Civil War. (Although Maryland is now considered part of the Mid-Atlantic region, it was a slaveholding state until 1864.) Lavinia Dundore organized the Maryland Equal Rights Society in Baltimore in 1867 to work for suffrage. The Society held a well-attended convention in 1872 with several national suffrage activists delivering speeches or sending letters of support, but by 1874 it had disbanded.

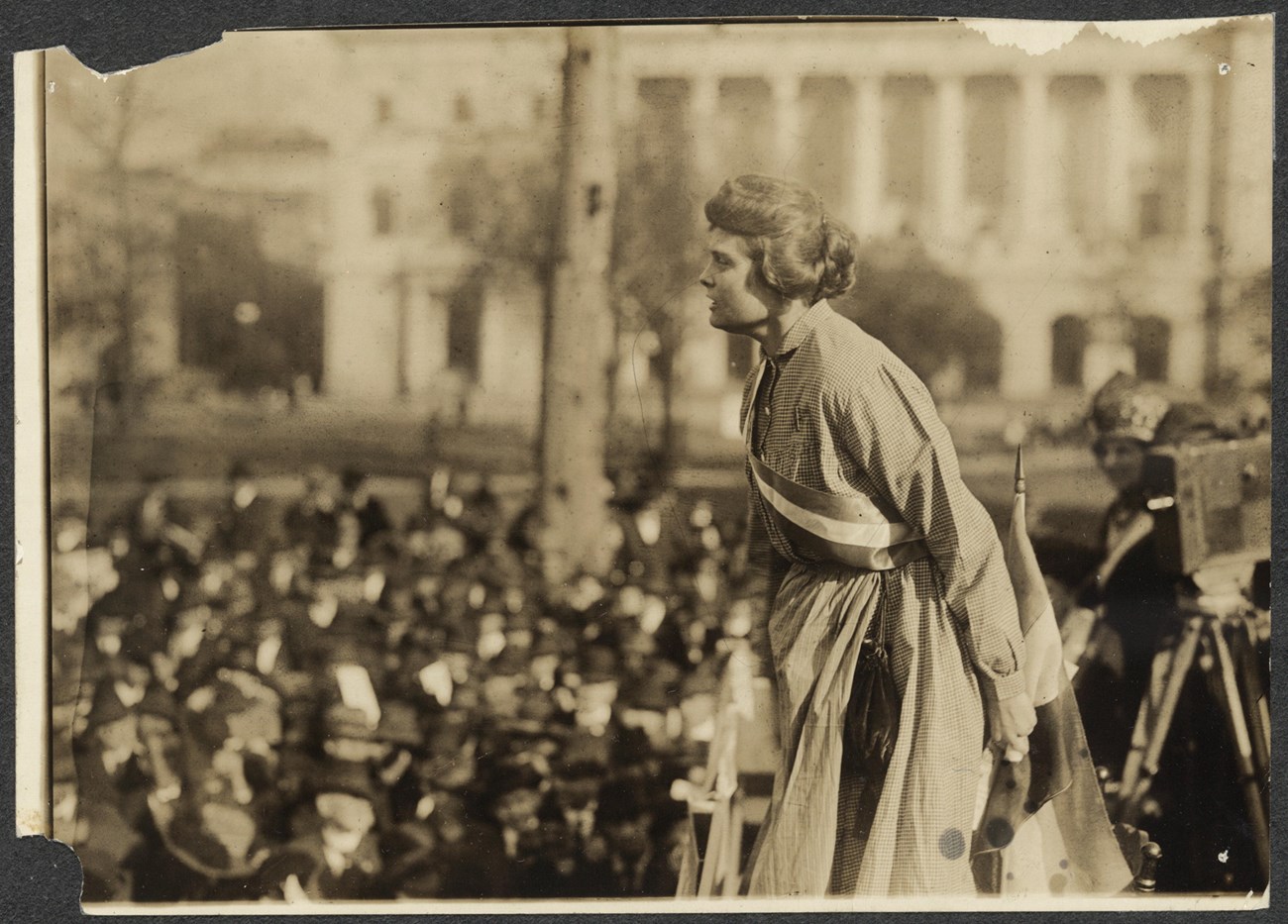

Bain News Service, Library of Congress

New Organizations in the 20th Century

In the twentieth century, there were at least three major woman suffrage organizations that were active in Maryland. The Maryland State Suffrage Association, the Just Government League of Maryland, and the Equal Suffrage League all organized events and held meetings throughout the state to fight for the right to vote. Members of the state organizations also joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and sent delegates to conventions around the country. In 1906, NAWSA held its annual convention in Baltimore at the Lyric Theatre. Susan B. Anthony delivered her final speech there months before she died.Maryland suffragists made sure to be visible throughout the state, especially at important community events. They set up booths at county fairs, drove cars decorated with banners and flowers in local parades, even entered a suffrage boat in a town regatta near Annapolis. Maryland welcomed “General” Rosalie Jones and her suffrage pilgrims during their hike through the state on the way from New York to Washington, D.C. for the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession. Maryland suffragists sent a delegation to the procession also, riding a special train from Baltimore to Washington called the “Suffrage Special.” Two years later, they organized their own suffrage hikers on several trips throughout the state, led by “General” Edna Latimer. Latimer also campaigned around the state with Lola Trax on a pilgrimage in a horse-drawn covered wagon called a Prairie Schooner adorned with “Votes For Women” flags.

Although the early Equal Rights Society was integrated, by the twentieth century, white suffragists in Maryland usually excluded African American women from participation. As in many parts of the country, Black women in Maryland formed organizations that worked for civil and social uplift for the community, including women’s right to vote. Augusta Chissell formed the Progressive Women’s Suffrage Club in Baltimore in 1915 to work for the enfranchisement of all women in the state. After the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, she wrote a column for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper called “A Primer for Women Voters” to help guide and educate women in their new civic role.

Despite all their work, Maryland suffragists were unsuccessful in winning the vote statewide. Several measures over the years to enfranchise women were voted down in the Maryland legislature. A few Maryland towns offered extremely limited suffrage to women. In Annapolis, women voted in bond elections beginning in 1900 but could not vote for any elected officials. The town of Still Pond in Kent County allowed women taxpayers to vote in municipal elections in 1908. Although the town charter adopted in Loch Lynn Heights in Garrett County should have granted women to vote in local elections, it doesn’t appear that women were ever permitted to participate.

National Woman's Party records, Library of Congress

Maryland Women Cause Trouble

Maryland women also joined the national movement for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution enfranchising women. Many Marylanders participated in demonstrations such as the National Woman’s Party’s pickets of the White House and several went to jail. Lucy Branham of Baltimore was an especially active protester. She was arrested several times and served sentences in the Occoquan Workhouse and the District jail. She participated in the “Prison Special,” a 1919 nationwide tour by rail of women who had been imprisoned for their demonstrations. They wore replicas of their prison dresses to highlight the oppression of women’s disfranchisement.After decades of arguments for and against women's suffrage, Congress finally passed the 19th Amendment in June 1919. After Congress approved the 19th Amendment, at least 36 states needed to vote in favor of the amendment for it to become law. This process is called ratification.

On February 20, 1920, Maryland voted against the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. By August of 1920, 36 states ratified the amendment, ensuring that in every state, the right to vote could not be denied based on sex.

National Woman's Party records, Library of Congress

Maryland Fights Back

Shortly after the 19th Amendment was passed in 1920, Judge Oscar Leser sued the state of Maryland to remove the names of two Baltimore women from the list of registered voters. His position was that the Maryland constitution granted voting rights only to men, and that Maryland had not ratified the 19th Amendment.

In January 1922, the United States Supreme Court heard arguments in the case. Leser's arguments to the Court were threefold: 1) that the character of the proposed amendment excluded it from being added to the Constitution; 2) that since many of the states that ratified the 19th Amendment had state constitutions prohibiting women from voting, they were unable to decide otherwise as a matter of established law; and 3) that the state legislatures in Tennessee and West Virginia had not followed proper procedure in ratifying the 19th Amendment.

In a unanimous certiorari decision issued on February 27, 1922, Leser v. Garnett, 258 U.S. 130 (1922), the Supreme Court ruled against Leser, confirming the constitutionality of the 19th Amendment. In their decision, they responded to each of his arguments as follows: 1) Since the similar 15th Amendment, which determined that voting rights could not be denied on account of race, had been accepted as valid law for over fifty years, the 19th Amendment could not be considered invalid; 2) When states ratified the 19th Amendment, they were acting in the federal sphere, which "transcends any limitations sought to be imposed by the people of a state"; and 3) Since both Connecticut and Vermont had also ratified the 19th Amendment before the case was heard (making 36 states, even if Tennessee and West Virginia were invalid), the validity of the Tennessee and West Virginia processes was moot. The court also said that, since the Secretaries of State of Tennessee and West Virginia had accepted the ratifications, that they were necessarily valid.

On March 29, 1941 Maryland voted to ratify the 19th Amendment. The vote was not certified until February 25, 1958.

Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000364/

Maryland Places of Women’s Suffrage: Still Pond Historic District

The Still Pond Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, includes the former site of the town hall. It was here that the women of Maryland cast their first ballots - 12 years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Residents such as Anna Baker Maxwell, Jane Clark Howard, and Lillie Deringer Kelley voted in the local election. That year, the town recognized the suffrage rights of women over the age of 21. Fourteen women were registered, including two African Americans. The town later repealed this rule and women were once again left without the vote until 1920.

The Still Pond Historic District is an important place in the story of ratification. It listed on the National Register of Historic Places.