Last updated: September 28, 2017

Article

Brief Maritime History of Florida

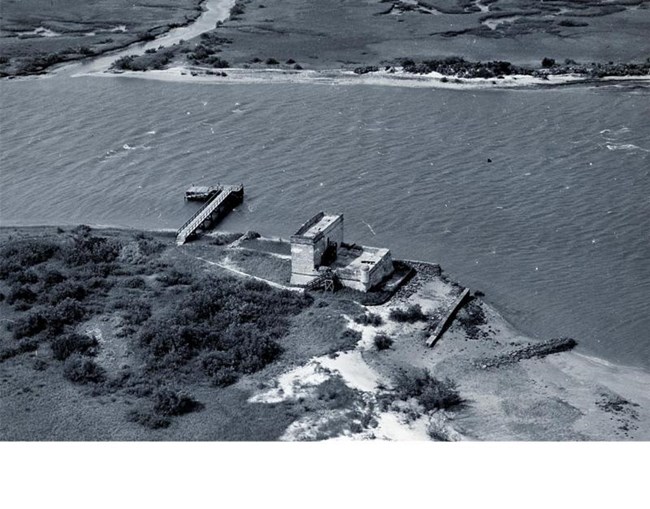

Image Courtesy of National Park Service

A long and flat peninsula surrounded by the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean and the Atlantic Ocean, Florida has a long and rich maritime history. The size and shape of Florida, along with its natural features like reefs, shoals, water depth, currents, locations of rivers and inlets and the weather, have affected where people lived and where vessels wrecked.

For at least 12,000 years, people have been living in Florida. Those earliest inhabitants would not recognize their home today, because the sea level is 20 to 50 fathoms higher and has covered nearly half of the Florida peninsula. Many people lived near springs and sinkholes and along rivers and near the coasts in areas like present-day Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, relying on fresh and saltwater fish and shellfish as important parts of their diet. The archeological remains at some of the earliest places they lived now are underwater and on the bottom of rivers and springs and offshore on the continental shelf.

From at least 6,000 years ago, the native people of Florida traveled the waterways and coasts by canoe, facilitating communication and trade among the tribes. About 300 prehistoric canoes have been found in more than 200 sites in Florida.

In the late 1400s and early 1500s, looking for a faster way to Asia by sea, European explorers sailed west and ran into the Americas. Seeing new resources to exploit, people to convert and lands to claim, the Spanish, the French and the English sent the military, missionaries and colonists to establish a foothold and expand their areas of control. The first evidence of a European encounter in Florida is the arrival of Spaniard Juan Ponce de Leon in the vicinity of present-day St. Augustine in 1513. Ponce de Leon named the land La Florida and attempted to circumnavigate what he thought was an island, sailing south to the Keys, naming a cluster of islands Las Tortugas and sailing north to present-day Tampa.

Ponce de Leon was followed by fellow Spaniards Panfilo de Narvaez who, in 1528, landed near present-day Tampa Bay and proceeded north to the area now known as Apalachee, and Hernando de Soto who, in 1539, landed in Tampa Bay, spent five months in what is today Tallahassee, and whose explorations of southern North America are commemorated at De Soto National Memorial. In 1559, Spaniard Tristan de Luna y Arellano established a short-lived colony at Pensacola Bay but lost all except three of his supply ships to a hurricane. The Emanuel Point shipwreck site (not included in this itinerary because of the wreck's fragility and poor diving conditions at the site) discovered in 1992 by the Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research may be one of his lost ships.

In 1562, the French sent Jean Ribaut to Florida. He marked a spot on the St. Johns River for future settlement and then headed north to establish Charlesfort, which failed, in present-day Parris Island, South Carolina. Two years later, Rene Goulaine de Laudonniere established a French Huguenot settlement and Fort de la Caroline along the St. Johns River.

In 1565, Spaniard Pedro Menendez de Aviles captured Fort Caroline in a brutal fight with the French and established St. Augustine, the first permanent European colony in North America. In 1567, Frenchman Dominique de Gourgues recaptured Fort Caroline. In 1569, the Spanish built a watchtower at Matanzas Inlet to watch the horizon and warn St. Augustine of approaching ships, a strategy that failed them in 1586, when Englishman Sir Francis Drake attacked and looted St. Augustine. The French effort to establish a colony in Florida is memorialized today at Fort Caroline National Memorial.

From the late 1500s through the 1700s, the Spanish sent annual convoys of merchant and military escort vessels from Cuba to Spain. Referred to as the Spanish plate fleets, the ships carried gold, silver and gemstones from the mines of Mexico and Peru, and porcelains, silks, pearls, spices and other highly sought goods from Asia that reached the Americas via the Spanish Manila Galleon fleet that crossed the Pacific.

The homeward bound Spanish plate fleets followed the Gulf Stream through the Straits of Florida and up the coast of North America before heading east for the Azores and Spain. The Spanish built Castillo de San Marcos and other coastal forts and settlements in Florida to provide protection from French and British raiders and pirates, and assist in saving survivors and salvaging cargoes from vessels that wrecked along Florida's shores as a result of hurricanes and mishaps.

Over the years, many Spanish ships were lost off the Florida coast with the greatest disasters suffered by the fleets of 1622, 1715 and 1733. During the 20th century, the remains of a number of lost ships have been found including the Nuestra Senora de Atocha from the 1622 fleet, the Urca de Lima from the 1715 fleet and the San Pedro from the 1733 fleet.

During the 1600s and 1700s, the Spanish, French and English continued to fight over territory and religion in Florida. The British in Georgia and South Carolina attempted to push southward and the French moved eastward along the Gulf Coast from the Mississippi River valley. The Spanish relied not only Castillo de San Marcos to protect St. Augustine, but began construction of Fort Matanzas in 1740 for additional protection from the south.

During the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739 through 1748) between Spain and Great Britain, the Royal Navy patrolled the Caribbean and the North American coastline. One ship that was lost during this time was the HMS Fowey, the wreck of which is located within the boundaries of Biscayne National Park and which has been extensively studied by the National Park Service and Florida State University.

In 1763, under the Treaty of Paris, Spain gave Britain control of Florida in exchange for Havana, Cuba, which the British had captured during the Seven Years' War (1756 through 1763). That same year, the British built a fort overlooking the entrance to Pensacola Bay. Spain captured Pensacola in 1781 and regained control of the rest of Florida in 1783, when Britain gave Florida to Spain in exchange for the Bahamas and Gibraltar. Around 1797, Spain built two forts at Pensacola Bay in the vicinity of the earlier British fort. Little physical evidence of these forts remains but what does remain is preserved at Gulf Islands National Seashore.

Although Britain's control of Florida was brief, its effect on the economy and settlement was substantial. As the British population increased and slaves were brought in, colonial plantations and other industries sprouted and flourished, exporting their products to other British colonies and trading illegally with Spanish Louisiana and Mexico. This was made possible because surveyors mapped the landscape, land grants were given out, the first road was built and a packet system of shipping by rivers and along the coasts was introduced. This economic prosperity and maritime trade continued after Britain ceded Florida to Spain, with exports to neighboring Gulf Coast and Eastern seaboard areas, the Northeast and as far away as Europe.In 1763, under the Treaty of Paris, Spain gave Britain control of Florida in exchange for Havana, Cuba, which the British had captured during the Seven Years' War (1756 through 1763). That same year, the British built a fort overlooking the entrance to Pensacola Bay. Spain captured Pensacola in 1781 and regained control of the rest of Florida in 1783, when Britain gave Florida to Spain in exchange for the Bahamas and Gibraltar. Around 1797, Spain built two forts at Pensacola Bay in the vicinity of the earlier British fort. Little physical evidence of these forts remains but what does remain is preserved at Gulf Islands National Seashore.

Spain ceded Florida to the United States as part of the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819, and Florida became a U.S. Territory in 1821. Coastal trade with other markets continued to expand and towns like Jacksonville, Pensacola and Tampa became important ports. After becoming a U.S. Territory, the U.S. Government began building a series of lighthouses as aids to navigation along the coasts of Florida to mark dangerous headlands, shoals, bars and reefs. Information about historic lighthouses in Florida has been recorded by the National Park Service in its Inventory of Historic Light Stations and by the U.S. Coast Guard.

The U.S. Navy has played a prominent role in Florida's maritime history. In the 1820s, the U.S. Navy was called upon to protect ships off Florida's coasts from pirates that plagued merchant ships in the Caribbean. One of the patrol ships was the USS Alligator lost near Islamorada while escorting a merchant convoy. In 1826, construction began on the Pensacola Navy Yard and four forts to defend it. What remains of Fort Pickens, Fort Barrancas and Fort McRee, which were built overlooking Pensacola Bay in the vicinity of the earlier British and Spanish forts, is preserved today within Gulf Islands National Seashore. Near the end of the 19th century, and as a result of the Spanish-American War, Tampa and other Florida ports became staging areas for tens of thousands of U.S. troops and supplies headed to Cuba. With the advent of manned controlled flight and the building of aircraft carriers and seaplanes, an aviation training station was established by the U.S. Navy at Pensacola in 1913 and another in Jacksonville in 1940.

Following statehood in 1845, Florida's economy became stronger and the principal ports shipped vast quantities of citrus, cotton, lumber and other products to the Atlantic states, the Caribbean and Europe. The Federal government began construction of coastal forts including Fort Taylor in Key West and Fort Jefferson on Garden Key in the Dry Tortugas to better control navigation through the Florida Straits. Although Fort Jefferson never was finished, construction continued for 30 years and vast quantities of bricks were shipped to the key in flat-bottomed steamboats like that found at the Bird Key wreck, which was lost while transporting bricks.

Seceding from the Union in 1861, Florida joined the Confederacy. During the Civil War, Florida's ports were blockaded by the Union and blockade runners delivered supplies needed by the Confederacy in exchange for Florida products. Although there were some vessel casualties on both sides, the major naval battles took place in states north of Florida. One unfortunate casualty in Florida waters was the Union transport ship Maple Leaf that struck a Confederate mine.

After the Civil War, tenant farmers and sharecroppers took over plantation lands, and agriculture, cattle ranching, lumber, manufacturing and extractive industries like phosphate mining became important, prompting improvements in transportation. Railroads expanded across the state connecting the ports and the interior, and steamboats like the City of Hawkinsville, SS Tarpon and SS Copenhagen began providing regular passenger and freight service on inland waterways like the St. Johns River and ocean service to international destinations. Tourism flourished with steamboat tours and hotels near rail lines.

During the late 19th century, the Federal government and local port authorities made improvements to channels and harbors and charted and mapped Florida's waters. These improvements, along with technological advances in navigation and shipbuilding during the 20th century, helped propel Florida's ports to global prominence in trade and commerce and the cruise industry and marine recreation. Florida may well hold the record for the number of pleasure boats used by sport fishermen, jet skiers, wind-surfers, power boaters, sail boaters, water-skiers and scuba divers.

The Florida Keys contain the only coral reefs in the continental United States, making it a haven for fish and coral. These same reefs are hazards to navigation. In this Florida Shipwrecks: 300 Years of Maritime History travel itinerary, we highlight just a few of the myriad marine casualties that have occurred over the centuries in the Keys and elsewhere in the waters of Florida.