Part of a series of articles titled The M'Clintock House & Women's Rights: Opportunities for Learning .

Article

The M'Clintock House & Women's Rights: Opportunities for Learning (2: Social Movements and Early Settlement)

Library of Congress.

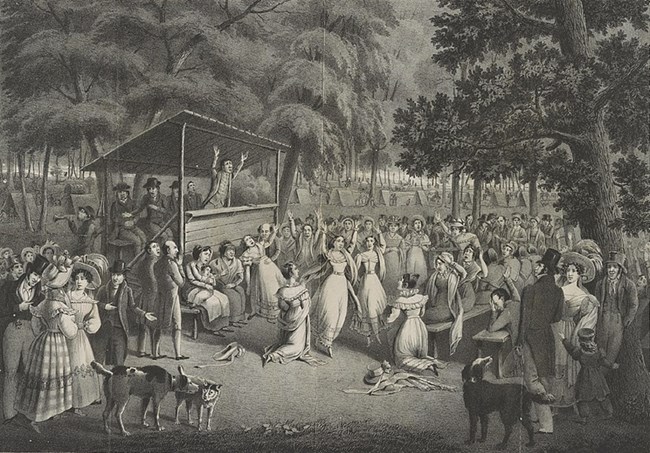

Reform movements of the early 1800s spurred the colonization of territory in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, a religious revival movement, shaped the settlement of New York State as Americans traveled to the region for religious gatherings. The Second Great Awakening also informed the abolitionist movement, the early women’s suffrage movement, and more. Explore the maps and readings below to learn more about the social movements and settlement of early America.

In the 1790s, the series of Protestant revivals known as the Second Great Awakening began in Connecticut. Though these revivals varied according to time and place as they appeared over the next 50 years, most featured preachers who encouraged individuals to experience an intensely emotional conversion that would lead to living in a more moral way. They also claimed that men and women could learn not to sin, a position that suggested people could control their own salvation. This belief, which contradicted the earlier teachings that an individual's fate was predestined, also spread in the early 19th century.

Revivals had one of their biggest influences in upstate New York. Rapid changes there in politics and economics had left many men and women struggling to find their place in a new world. The revivals, which offered spiritual guidance and emphasized the importance of the individual, therefore appealed to many people. Revivals fired through upstate New York so often and so strongly that the area became known as the "Burned-Over District."

The Second Great Awakening had a further effect on the region. Many people there, as in other parts of the country, took its lessons about self-determination and applied them to their lives outside of church. The Burned-Over District became a hot-bed of activity for many of the reform movements appearing in antebellum America: abolition of slavery, developing public education, and reducing the consumption of alcohol. In 1848, citizens of Waterloo and Seneca Falls, two towns in the Burned-Over District, came to play a critical role in the early struggle for women's rights by organizing the First Women's Rights Convention.

Settlers began to flood into western New York after the Revolutionary War, first from New England, then from Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Most came in search of better economic opportunities, hoping in particular to find land fertile enough to support a successful farm. Early settlers usually came in wagons, which required traveling on roads that were rough, frequently muddy, and almost always slow.

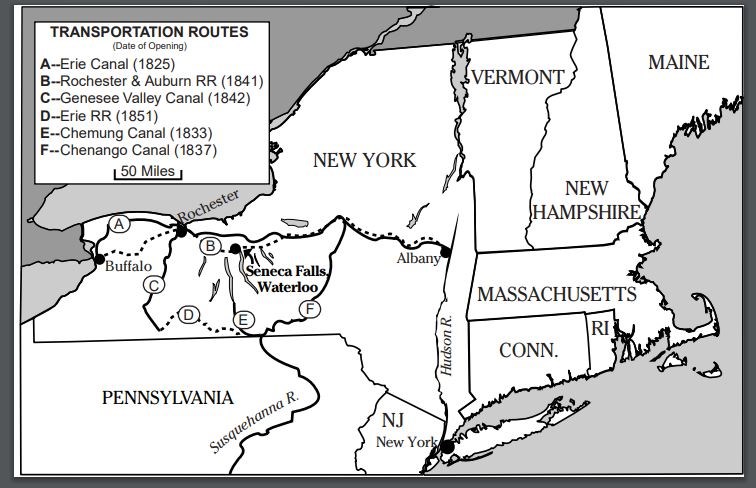

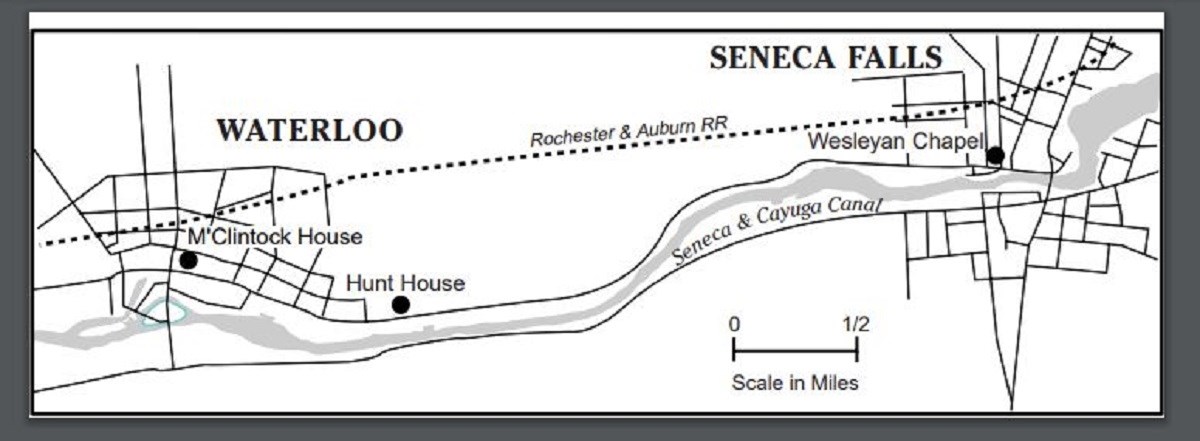

Towns quickly developed along most transportation routes. In many respects Waterloo and Seneca Falls, two towns located between the Finger Lakes and the Erie Canal, were typical of the communities that developed in upstate New York in the first half of the 19th century. There travelers found services, farmers bought and sold goods, and people from throughout the area participated in social and governmental activities.

Study the map below and consider the following questions:

1. What state are the towns of Waterloo and Seneca Falls in and what region of the United States is that called?

2. List four kinds of transportation people used to travel between Waterloo and Seneca Falls. What evidence from the map supports your answer?

3. What industries do you think might be present in 19th century Waterloo and Seneca Falls? What kinds of paid jobs did people hold there? Use evidence from the map and resding to support your answer.

National Park Service.

Waterloo was founded in the late 1700s when New York state negotiated treaties that deprived the Cayuga and Seneca nations of their land. The nearby Seneca River attracted settlers who saw that it could power mills. The town also benefitted from its position along an east-west turnpike and along a canal that linked two local lakes. In 1828, improvements to the Cayuga and Seneca Canal connected Waterloo to the Erie Canal. In 1841, the Rochester and Auburn Railroad began to serve Waterloo.

By 1840 Waterloo had become a community of nearly 3,600 people, while Seneca Falls, less than four miles away, added another 4,000 residents to the area. Both featured a growing number of homes, shops, and churches, while farms filled the surrounding countryside.

Waterloo, New York powerfully illustrated the political, economic, and social changes taking place throughout the United States during the first half of the 19th century. Politics became increasingly democratic for white men, most notably through the removal of requirements that a man own property in order to vote. Over time voters listened less to the wealthy and powerful, learning instead to make choices for themselves. Successful candidates for public office learned to appeal to a variety of voters, frequently emphasizing the wisdom and importance of the "common man" who made up a large section of the electorate.

The economy was developing in new ways. Across the country, innovations in transportation dramatically reduced the cost of shipping, lowering the price of goods and creating new trading opportunities. Better transportation was especially important because of the spread of the market economy. By the middle of the 19th century it had become much more common for a family to buy many of the products it needed, even if they had to come in some cases from hundreds of miles away. The growth of a national "market" encouraged people to specialize in the production of a small number of goods, selling them in order to receive money to pay for other needs. The Industrial Revolution contributed to this pattern, as factories began turning out large numbers of similar items. New plants in Waterloo, for example, began manufacturing woolen goods, a change that created new types of jobs.

Map Discussion Questions:

1. What methods of transportation served Seneca Falls and Waterloo?

2. The businessmen of Seneca Falls helped pay to bring the railroad to their town. Why would they do that?

3. Do you think the people in the two towns would have interacted much? Why or why not?

Religion played a crucial role in the lives of the M'Clintocks. They were active members of the Society of Friends or, as they are commonly known, the Quakers. Since its founding in 17th century England, the Society has taught that everyone has an "Inner Light" that allows direct access to God. Following that Light leads to spiritual development. The Quaker belief that the Inner Light exists in all people has led them to think that no individual is better or worse than another. This emphasis on equality has helped make them one of the most socially active religious groups in the United States; they were, for example, some of the strongest opponents of slavery.

The M'Clintocks were members of a branch of the Quakers known as the Hicksites, who had left the main "meeting" in the 1820s. This split centered on the most important source for guidance: the traditional or Orthodox branch relied more heavily on the Bible, while the Hicksites, influenced by revivalism, placed more emphasis on individual conscience. Many Hicksites were energetic reformers, a tendency the M'Clintocks illustrated. They held temperance (opposition to alcohol) meetings in the room above the drug store and campaigned for better treatment of American Indians. They were strong opponents of slavery: Mary Ann and Thomas petitioned Congress to outlaw the practice, and Elizabeth helped organize fund-raising "fairs" that supported anti-slavery societies.

In the summer of 1848, however, the M'Clintocks were among 200 people in and around Waterloo who decided to leave the Hicksite meeting. They believed the Hicksites were still not active enough on social issues--many meetings refused anti-slavery speakers the use of their buildings, for example--or committed enough to sexual equality. They also wanted local meetings to have more autonomy. They therefore formed the Congregational Friends of Human Progress, a church open "to Christian, Jew, Mohammedan and Pagan" as long as that person was committed to improving society. In the guidelines for their new church, Thomas M'Clintock wrote that in the Progressive Friends, "not only will the equality of women be recognized, but so perfectly, that in our meetings, larger and smaller, men and women will meet together and transact business together." Even the Hicksites, who were far more liberal than most Quakers (who were in turn more liberal than most other churches), had separate services for the two sexes. It was this dedication to women's rights that helped bring the M'Clintock House into history.

Discussion Questions:

1. What changes were taking place in western New York in the first half of the 19th century?

2. Do you think the Burned-Over District would have been a good place to find supporters of abolition and women's rights? Why or why not?

3. How did the M'Clintocks' religious beliefs shape their commitment to social reform?

Tags

- women in history

- women’s history

- women’s rights

- women’s suffrage

- suffrage

- 19th amendment

- seneca falls convention

- womens rights national historical park

- social history womens history

- social history

- religious history

- religious society of friends

- abolitionist movement

- new york history

- shaping the political landscape

- migration and immigration

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

Last updated: August 29, 2019