The Latino Crucible: Its Origins in 19th-Century Wars, Revolutions, and Empire

This American Latino Theme Study essay explores various 19th and 20th century wars and revolutions in the U.S. and several Latin American countries and discusses not only their effects on the physical expansion of America, but also how these actions caused Latinos from Mexico, Cuba, and Puerto Rico to be territorially incorporated into the U.S.

by Ramón A. Gutiérrez

The people who now reside in the U.S. and call themselves Latinos have long and complex historical genealogies in this country. Many of them entered the U.S. willingly as immigrants in the 20th century, but just as many were territorially incorporated through America's wars of imperial expansion in the 19th century. As many ethnic Mexican residents of the Southwest correctly explain, "We did not cross a border; the border crossed us." Or as others oft remark, "We are here because you were there." To understand how and why Mexicans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans, the three groups that today constitute the bulk of American Latinos, first entered the U.S., let us imagine two very separate zones of imperial concentration in the Americas that were born in 1492 with the voyages of Christopher Columbus.

The first area of Spanish imperial settlement in the Americas was in the Caribbean, with Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola as its principle sites. The native inhabitants of these islands were few in number at contact, were quickly decimated by European diseases, and labor demands and their labor was just as rapidly replaced by African slaves. This is why the Spanish Caribbean has long had such a strong African cultural tradition and such a distinct racial legacy around issues of blackness. Cuba is by far the largest Caribbean island, almost eleven times bigger than Puerto Rico. For four centuries, Cuba was one of the most productive and prosperous of Spain's colonies. It was the staging point for the early Spanish expeditions of exploration and conquest in the Americas, and it was through the port of Havana that most trade flowed between Europe and Spanish America. Florida and Louisiana by virtue of their geographic proximity and trade were closely tied to Cuba in the colonial period and have remained in its cultural orbit ever since. Of the 50.5 million Latinos now living in the U.S., 12 percent or 6.3 million trace their ancestry back to these initial Spanish settlements in Cuba and Puerto Rico.

The largest group of Latinos in the U.S. is from Mexico, representing about 63 percent of the group's total and numbering 31.7 million by the 2010 census count. In the early 16th century, expeditions of exploration originating in Cuba learned of the wealthy Aztec Empire in the Valley of Mexico with its immense population of some 20 million and its streets putatively paved in gems, silver, and gold. The Spanish conquest of the Aztecs followed in 1521, and when that was completed expeditions of conquest radiated out from Mexico, eventually subjugating the Inca Empire in Peru in 1532. This zone of Hispanic presence in the New World was centered in Mexico City and had a dense indigenous population that supplied its labor needs under both Aztec and Spanish rule. Since relatively few African slaves were ever imported into this colony, its racial politics have focused on mestizaje, or racial mixing between whites and Indians, while largely ignoring its African heritage.

Mexico was tied to Europe through established trade routes between Havana and Veracruz, and connected to Asian markets by the convoys that regularly sailed between Mexico's Pacific port at Acapulco and Manila Bay in the Philippines. For our story about the devolution of Spain's American colonial empire and the genesis of Latinos, we focus only on Mexico's attempts to settle its far north, what became the states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. In the 18th century, the mines of northern Mexico were producing the bulk of the world's silver. The settlement of New Mexico, Texas, and California became an imperative for Spain as a way of protecting these operations and thwarting English, French, American, and Comanche threats.

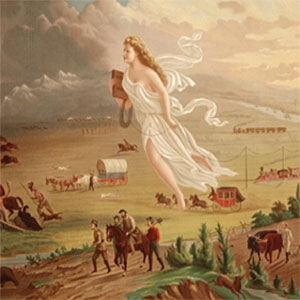

Many Latinos date their origin as subjects or citizens of the U.S. to the period between 1800 and 1900. This essay roughly takes these dates as its temporal beginning and end. The U.S. began 1800 as 16 states with no major territorial possessions. It ended 1900 having fulfilled a continental ambition, with sovereignty over Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Oregon, and Alaska, and with an overseas empire that included Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and Hawaii. This rapid expansion gave rise to a legitimating nationalist myth of empire that became popularly known as Manifest Destiny. In its most elemental form, Manifest Destiny asserted that God providentially had chosen the Anglo-Saxon race of the U.S. to bring civilization to inferior, dark peoples, to sweep away monarchy and replace it with democracy, to establish republican forms of government premised on Protestantism, and to generously help benighted pioneers and people who occupied the spaces America coveted. Manifest Destiny was a complex time/space matrix of ideas variously inflected, but unitarily evolutionary and racialist, explaining America's need for new lands, ports, and markets, for secure national borders, and most of all, for its God-ordained destiny to greatness.

Revolutionary Stirrings

At the end of the 18th century, Europe and the Americas were overcome by a number of revolutions that profoundly transformed the colonial empires England, France, and Spain had built. News of the French Revolution rapidly spread to Saint-Domingue, France's most profitable colony in the Caribbean, which was then producing with African slave labor much of the sugar and coffee consumed in England and France. From 1788 to 1791, as the ties of empire weakened and the French monarchy was swept aside the island's white planters and settlers mainly fought among themselves divided as royalists and separatists, but united in wanting self-rule, the continuation of slavery, and their racial privileges as whites. As the revolution became more radical in France, extending in 1791 full legal equality to all free men, whatever their color, this proclamation inspired slaves to seek their own freedom too, sparking revolts on Saint-Domingue, which quickly left many of the island's plantations destroyed and some 2,000 whites dead. Spain and England came to the aid of the planters on Saint-Domingue, but just as they did France abolished African slavery in 1794, the first country in the world to do so, sparking slave revolts in Spain and England's colonies. What began as an independence movement in Saint-Domingue in 1791, quickly devolved into a genocidal racial war against whites and French power, and ending in 1804 with the creation of the Republic of Haiti.

Enlightenment ideals about equality, citizenship and inalienable rights similarly infected Spain's colonies. These ideas proved particularly incendiary when compounded by local grievances about heavy taxation, the over regulation of trade, the unity of church and state, and the place of the Indian in the colonial scheme. Napoleon's invasion of Spain and his removal of the Bourbon dynasty from its throne in 1807 provoked a crisis of royal authority both in Spain and in the Americas, quickening independence in the latter, as one region after another declared themselves independent states. By 1825, only Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines remained under Spanish rule.

Contesting Manifest Destiny

The victors of war always control the writing of history, forging and fixing exactly how events will be represented, remembered, and studied. This is particularly the case in American historiography because the narratives of the nation's development have been so thoroughly interested in denying empire and erasing the resistance of those peoples who were swept aside by conquest. Indeed, many American history books still attest that the nation's territorial expansion was motivated by benevolence, by an Anglo Protestant civilizing mission to rescue and uplift racialized savages, even denying genocide, calling it by a more genteel name "Indian removal," and asserting that there was little opposition to American rule.

American history textbooks still largely narrate the 19th century as a series of pivotal wars, from the Texas Revolution (1836), to the U.S.-Mexico War (1846), to the Spanish American War (1898). When American history is told and taught this way Latinos all but disappear. Mexican Texans and Anglos united during the Texas Revolution against a Mexico they deemed tyrannical. When we as modern Americans are urged to "Remember the Alamo," however, it is a call to remembrance not of this unity but of the butchery Mexico unleashed to crush Texan self-rule. The popular names we still use to refer to America's expansionistic wars intentionally erase many of the major actors, certainly all of the vanquished, particularly those who became subjects and second-class citizens of the U.S. by virtue of their race and subjugation. Mexicans, Tejanos, and Comanches are often missing from the imperial narratives of the Texas Revolution. Comanches, Navajos, and the old Spanish/Mexican residents in New Mexico, Arizona, and California are rarely mentioned in accounts of the U.S.-Mexico War. Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and Filipinos are absent from the title of the Spanish American War, and even more so missing from the narratives of their independence struggles. My goal here is to re-inscribe these missing groups, consciously shifting the optic from war names to war dates to incorporate more fully the histories of forgotten groups.

The War of 1836

At the beginning of the 19th century Spain's settlements east of the Mississippi River in Louisiana and Florida, changed hands a number of times. In 1803, the U.S. paid France 15 million dollars for the Louisiana Territory, an area that stretched from New Orleans all the way north to portions of the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, encompassing some 828,000 square miles. When Spain ceded Florida and Louisiana, it encouraged its subjects to move westward into Texas offering them virtually free, tax-exempt land.

Who exactly owned Texas was a question of considerable contestation after 1803. The U.S. claimed it as part of the Louisiana Purchase, something Spain patently denied. In 1805, the Viceroy of New Spain commissioned a boundary study, which resulted in Father José Antonio Pichardos' 3,000-page Treatise on the Limits of Louisiana and Texas, issued in 1808. The report arrived too late. In 1807, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain, placed his brother Joseph on the throne, and lacking now a legitimate monarch, accelerated the popular momentum for declarations of independence, including Mexico's in 1810. The future of Texas was now something Mexico would have to resolve.

Anglo colonists from Louisiana, who had rapidly seen the boundaries of political authority under which they lived shift from Spain to France, to the U.S., began moving into Texas where land was abundantly cheap and slavery could be maintained. Moses Austin, then a resident of Missouri, petitioned the town council of San Antonio de Béjar for an empresario grant in 1819, to settle 300 families, taking it upon himself as the agent or empresario to fulfill all the conditions of the contract. The Governor of Coahuila and Texas approved it, but before possession could take place, Moses Austin died. It fell to his son, Stephen F. Austin, to settle the families. Each immigrant family was granted one section of land (640 acres) with the clear understanding that the settlers had to be former residents of Spanish Louisiana, had to swear allegiance to the monarchy, had to honor the language and culture of Texas and had to be Roman Catholic in faith. They agreed. They never really complied.

In the years that followed, the Mexican government awarded many more empresario grants. Why Spain and then Mexico eagerly welcomed Anglo settlers into Texas is best understood with a short digression to include another set of powerful historical actors in the region, Native Americans. In 1706, New Mexico's Spanish authorities reported that a group of Indians known as Comanches had entered the grasslands south of the Rio Grande. Though the observation was made in passing and seemingly without alarm, by the middle of the century the Comanches had become the major force in the southern plains, amassing contingents of armed and mounted warriors that often reached the thousands, significantly outnumbering anything Spain, France, England, or the U.S. could muster to resist their advances. Known to the Spanish as the indios bárbaros, these "barbaric Indians" were indeed formidable opponents. Remembered fearfully by the Spanish for their plundering and killing and for their looting and enslaving, they were, in fact, nimble political actors who often consciously played the local functionaries of European empires against each other to expand their own commercial trade networks in livestock, hides, and slaves. From the 1780s on the territory of their effective control expanded rapidly because of their acquisition of horses and arms, their development of remarkable equestrian skills and their unflinching humiliation of their competitors. By the 1840s, their lands reached from the eastern border of Texas at the Nueces River westward to New Mexico's western border, eventually extending to encompass the southern half of Colorado all the way south to the Mexican states of Zacatecas and San Luis Potosi, which were home to Spain's most lucrative silver mines. In this area the Comanches cut a swath of trade and terror few could match, prompting historian Pekka Hämäläinen to call it a Comanche Empire, which on the ground fully overpowered anything Spain, Mexico, France, England, or the U.S. could muster.

Spain began opening Mexico's northern provinces to rapid settlement, offering arms and large land grants, even to foreign immigrants after 1803, to stem Comanche raiding and American and English encroachments. Softening its highly restrictive trade policies to heighten communication and protection of its settlements, merchants from various countries were also allowed to enter Mexico's north. Soon they were traversing the Camino Real, which provisioned the silver mines in Zacatecas and San Luis Potosi, linking from south to north Mexico City, Zacatecas, Durango, Chihuahua, and Santa Fe; now connecting the Royal Road to Kansas City and Chicago.

In 1821, the Kingdom of New Mexico, which then encompassed what became New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah, was by far the most densely populated place in northern Mexico, with some 28,500 residents who called themselves Spaniards and 10,000 Pueblo Indians. California was second with a populace of 3,400 Spaniards and 23,000 mission Indians. Arizona counted about 700 Spaniards and 1,400 congregated Indians and Texas had roughly 4,000 Spaniards and 800 Indians in its mission settlements.

What Mexican settlers, Anglo immigrants, and merchants under the protection of various flags found as they entered to settle the northern Mexican provinces of Chihuahua, Nuevo Mexico, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tejas in the early 19th century were large ranches, dispersed farming settlements, and small towns. Many of them had begun as colonias, or colonies intended to fortify the frontier. By the 1820s, however, they were being increasingly attacked by the Comanches and were rarely able to defend themselves, leaving many of their settlements abandoned.

Foreign immigrants from the U.S. flocked into Texas quickly outnumbering the older Mexican tejanos. From 1823 to 1830, roughly 1,000 Anglo Americans arrived per year; in the 1830s the pace quickened to some 3,000 yearly, recruited mostly from Kentucky, Arkansas, and Louisiana. On the eve of the War of 1836, there were roughly 30,000 Anglo Americans residents, 5,000 black slaves, 3,470 Mexicans, a settled Indian population of 14,200, and a surrounding nomadic Indian population of 40,000 Comanches.

From the moment Anglo American colonists arrived in Texas, four issues dominated their relations with tejanos, with local authorities, and with the Mexican state: slavery, religion, Comanche raids, and representative government. Since the early 1800s, Spain had maintained that any slave who fled the U.S. and crossed the Sabine River into Texas would be considered free. In 1810, at the start of Mexico's independence war, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, the movement's first leader, abolished slavery as a way of gaining broader support. The revolution was crushed and slavery remained intact. Stephen F. Austin insisted that slavery was legal in Texas, which indeed it still was. The Mexican Constituent Congress of 1824 tried to abolish slavery hoping that by doing so it would curtail the Anglo immigrant onslaught. It failed. In 1827, the state Constitution of Coahuila and Texas declared: "No one is born a slave in the state from the time this Constitution is published in the seat of each district; and after six months the introduction of slaves is prohibited under any pretext." Stephen F. Austin persisted in defending slavery but to no avail. Finally, on September 15, 1829, Mexico's President Vincent Guerrero emancipated all slaves and prohibited all commerce in them, immediately heightening tensions with Texans who owned them and who began concocting various ruses to keep them.

Anglo Americans were also patently violating the terms of their settlement grants around issues of religion. A few Anglo American men married Texas Mexican women and converted to Catholicism. The majority did not. The federal Constitution of 1824 declared Roman Catholicism as the only sanctioned religion in the republic, immediately heightening conflict between Mexican Catholics and Anglo Protestants. In 1825, when the state legislature of Coahuila and Texas debated the colonization law that would soon govern settlements, Stephen F. Austin lobbied to get this requirement changed from "Catholic" to "Christian". Again, he failed.

If slavery and religion profoundly pitted tejanos against Anglo Americans, the Comanche threat they faced bound them together, but mostly in collective impotence. The national government's forces had been left too weakened by the wars of independence and could scarcely be marshaled to protect them. The Comanches effectively controlled most trade in the southern plains, sometimes peacefully trading their livestock, bison hides, and captives for iron works, guns and ammunition, but just as often raiding and taking what they wanted. What solidarity existed between Mexicans and Anglos in Texas had been forged through mixed marriages and common defense against Indian enemies who limited their movements and constrained their commerce.

Since its foundations in the early 1700s, Texas had been a region far removed from the centers of political power. Under Spanish rule, Texas was one of New Spain's Internal Provinces (Provincias Internas) governed by an intendant in Mexico City. With the Constitution of 1824, Mexico became a federal republic with Texas and its neighbor province Coahuila united as one state. Texas had minimal representation at the state capitol in Saltillo, constantly bristled about this fact, and regularly petitioned state and federal governments for more local control. They wanted the creation of more town councils (cabildos), trial by jury, the ability to use English in all legal and administrative matters, exemption from state taxes, the right to own slaves, religious tolerance, and a state-sponsored educational system.

Texas' first, but short-lived attempt at self-government came in 1826, when the Cherokee and Anglo residents of east Texas allied as the Republic of Red and White Peoples, most commonly known as the Republic of Fredonia. Calls for independence were again voiced in January 1832, when General Antonio López de Santa Anna staged a military coup in Mexico City, ushering in a centralist government. Texans, by far the most militant defenders of federalism in Mexico, again felt disenfranchised. Stephan F. Austin immediately traveled to Mexico City to make the case that Texas should be an independent state. Before learning that Santa Anna had rejected his proposal, however, he wrote the cabildo of San Antonio saying that they could begin the process. Austin's letter was intercepted. He was quickly imprisoned. While awaiting trial in Mexico City he penned and published his Exposition to the Public about Texas Affairs (1835) demanding Mexican statehood.

Fearing that Austin's detention might spark rebellion, the authorities quickly set him free. He found his compatriots in Texas fuming and badly divided on a course of action. Would it be Mexican statehood, autonomy in the form of an independent republic, or annexation by the U.S.? Even before Austin reached Texas, the settlers of Nacogdoches conscripted a militia eager to demand U.S. annexation. Meanwhile, back in Mexico City, the centralist government pointed to Texas as one of the problems federalism had created. Greater central control from Mexico City over this increasingly renegade province was what was needed.

Texans bolted. They did so on November 3, 1835. What they envisioned for themselves was still not clear. Stephen F. Austin assumed leadership over the military defenses of Texas, while Sam Houston turned to the recruitment of volunteers, money, and arms. On March 2, 1836, just after General Santa Anna's troops arrived to crush the rebellion, Texas finally declared its independence, elected David G. Burnet as president and Lorenzo de Zavala as vice president. Their Declaration of Independence recited anew their well-known grievances, most of which were already moot due to federal reforms. Elite tejanos were themselves divided on succession. Some of the prominent merchants and landowners—José Asiano, José Antonio Navarro, Juan Nepomuceno Seguín—supported it, while such powerful men as Carlos de la Garza and Vicente Córdova opposed it, wishing to remain loyal Mexicans and confident that succession was yet another Anglo ploy to continue slavery. They were correct. Tejanos immediately became apprehensive as they heard Anglo Texans openly declaring that Mexicans were unfit for self-government and republican rule. Mexicans were a cruel and cowardly breed of mongrels. They were indolent and ignorant, the Anglos maintained. Mexicans naturally had grave forebodings about such incipient racial conflict, which indeed would rapidly intensify after independence.

General Santa Anna and the Mexican Army moved quickly against the rebels. The first major defeat of the Texas patriots came on March 6 at the mission garrison of the Alamo. All 187 Texan defenders died; between 600 and 1,600 Mexican soldiers were killed. Santa Anna's troops next marched on Goliad, where another major contingent of Texans had gathered in defense of their revolution. Here too Texans were quickly overpowered, taken as prisoners of war, and on March 26, 1836, all 303 of them were executed. These defeats emboldened the Texans and attracted numerous volunteers from the U.S. "Remember the Alamo, Remember Goliad," became their battle cry. Sam Houston sallied forth with his troops and on April 21 captured Mexico's president General Santa Anna, decimating his forces at the Battle of San Jacinto. When General Santa Anna and David Burnet signed the peace treaty on May 14, 1836, Mexico promised to compensate Texas for destroyed property, release all prisoners, and vow never to wage war against Texas again. Texas was independent at last.

Though victorious, Texas was left impoverished by the war. Its principle irritant, the Comanches, had only been strengthened by the retreat of the Spanish and the defeat of the Mexicans. Texas could not pay its troops. Food was in short supply. Much of the arable land lay fallow and what had been planted had been destroyed. On learning of Texas independence, however, support poured in from the U.S. for reasons the editor of New York's Courier and Enquirer made clear: "War will now be carried into the enemy's country, where gold and silver are plenty, there will be fine picking in the interior. The war will never end until Mexico is completely our own and conquered."

In the decades that followed 1836, Anglo immigrants and their slaves rapidly flocked to Texas. Tejanos were increasingly outnumbered, so much so that by 1850 they were only five percent of the state's population. The American newcomers knew little of the area's history and quickly vaunted opinions that they were white and Mexicans were not. As Oscar M. Addison put it in the 1850s, Mexicans were "a class, inferior to common nigers [sic]." Anglos asserted that they were superior and Mexicans were inferior, that tejanos should toil for the benefit of Anglos, but not the inverse. During the second half of the 19th century, tejanos faced blatant discrimination, were segregated in limited social spaces, and encountered mostly abuse and neglect from government offices and officers, the most brutal coming from the Texas Rangers. Even elite status proved of little protection, as many Anglo newcomers seized their lands, claiming them as compensation for the destruction and bloodshed Mexican nationals had inflicted on whites during the revolution.

Tejano responses to the new racial order were various. In places where the two communities were sufficiently separated they retreated and accommodated, but remained resentful and suspicious of their fellow citizens. A few of the tejano elite assimilated and took up political posts in the new order, their loyalties always suspect, particularly whenever the harassment of tejanos broke out in violence and rebellion. Anglo rustling of tejano livestock became a daily fact of life, which was met with exact retaliation. Many tejanos dreamt of life free from Anglo control and consequently joined the failed movement to create the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840, which would have united that portion of Texas lying west of the Nueces River with Nuevo León, Zacatecas, Durango, Chihuahua, and Nuevo México. Here too their hopes were dashed. Tejanos joined local rebellions against Anglo domination, like those initiated by Juan Nepomuceno Cortina in Brownsville in 1859, and by Gregorio Cortez in Kenedy in 1901.

What almost a century of Anglo domination in Texas produced was an etiquette of race relations by which tejanos understood their subordination, and at least in public, accepted it and respectfully observed its rules. In the 1920s, one sociologist observed that tejanos always had to approach Anglos with "a deferential body posture and respectful voice tone." One also used the best polite forms of speech one could muster in English or Spanish. One laughed with Anglos but never at them. One never showed extreme anger or aggression towards an Anglo in public. Of course the reverse of this was that Anglos could be informal with Mexicanos; they could use 'tú' forms, 'compadre' or '˜amigo' and shout 'hey, cabrón' or 'hey, chingado' (son of a bitch) in a joking, derogatory way. Anglos could slap Mexicanos on the back, joke with them at their expense, curse them out, in short, do all the things people usually do only among relatively familiar and equal people.

The War of 1846

In the years following Texas independence, its annexation into the U.S. became a cause célèbre. During his presidential campaign in 1845, James Knox Polk made the annexation of Texas, Oregon, and California his central promise. Before his election, however, Congress approved the annexation on March 1, 1845. Mexico lodged a protest. It deemed annexation an act of war and immediately broke off diplomatic relations with the U.S. In a strange twist of irony, General Antonio López de Santa Anna's main campaign promise for the Mexican presidential election in 1843 was that he would re-annex the rebellious Texas province and defend California. Santa Anna won, soon learned of the annexation of Texas, and prepared for war. That President Polk dispatched John Slidell to Mexico with an offer to purchase California, New Mexico, and a western border for Texas at the Rio Grande for $30 million only made matters worse.

A contrived border dispute provoked hostilities between Mexico and the U.S. in 1846. Since Spanish colonial times the western boundary of Texas had been the Nueces River. The Congressional resolution annexing Texas listed no western border precisely because a previous bill listing it as the Rio Grande had been defeated. With Texas now annexed President Polk ordered General Zackary Taylor's 3,500 troops into the disputed territory between the Rio Grande and the Nueces, simultaneously sending Commodore John D. Sloat and the Pacific Squadron with instructions that if Mexico declared war Sloat should immediately seize California's ports. On April 25, 1846, General Taylor wrote President Polk saying, "hostilities may now be considered as commenced," reporting on a brief skirmish between Mexican and American troops in the disputed territory. In his May 11 message to Congress requesting a declaration of war, Polk contended, "after reiterated menaces, Mexico has passed the boundary of the U.S., has invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil." Senate Whigs ridiculed Polk's assertion saying that he had intentionally invaded Mexico to provoke a war. It was during the public debates over this contentious war that the notion of Manifest Destiny gained a name and tangible form. John O'Sullivan, editor of the Democratic Review and a great supporter of the war reasoned in 1845 that it was "Our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions."

The war against Mexico really had begun six months before its formal declaration. In December 1845, President Polk commissioned John C. Frémont for a "scientific" expedition to California. His arrival there with a band of armed men provoked local anxieties. They were quickly ordered to leave. Frémont feigned that he was simply headed to Oregon and needed supplies. On June 14, 1846, his intention became clear when a group of Americans arrested one of California's Mexican commanders, General Mariano Vallejo, and declared their independence. On July 5, Frémont was elected the head of the Republic of California and four days later, on July 9, Commodore John D. Sloat's forces marched inland to Sonoma, having previously taken San Francisco. Sloat declared California a U.S. possession, lowered the bear flag, and hoisted the stars and stripes.

The U.S. waged war against Mexico on four fronts. The Pacific Squadron took the ports of northern California by July 9, 1846. The Army of the West, under the command of General Stephen W. Kearny, took Santa Fe on August 15, 1846, and from there proceeded westward to southern California. Part of Kearny's company was dispatched south into Chihuahua. Under the command of Colonel Alexander Doniphan Chihuahua was occupied by early February of 1847.

The American strategy for the conquest and occupation of California was to take the northern ports first, then sail south to Los Angeles, where Robert F. Stockton's naval forces would reconnoiter with Kearny's army to take control of southern California. Both Kearny and Stockton encountered significant resistance from the local Californios, but by January 13, 1847, the invasion was secure.

With New Mexico and California nominally under American control by early 1847, President Polk next dispatched General Winfield Scott to occupy Mexico City. Arriving at the port of Veracruz with an armada on March 7, Scott proceeded to bombard the city until its residents surrendered on March 27. From there his troops advanced on Puebla, and then on Mexico City, which they occupied on September 15, 1847. Though Mexican President Santa Anna had led his troops bravely and had fought valiantly through tough battles and guerilla skirmishes, they were fighting a professional army that was well equipped and rigorously trained, and thus no match.

Nicholas P. Trist, the U.S. Peace Commissioner, arrived in Mexico City shortly after to negotiate the war's end. The Mexican government was in shambles. No one was prepared to negotiate with Trist the unfavorable terms he wanted to impose. The treaty called for Mexico to acknowledge the Rio Grande as the border with Texas, to surrender 55 percent of its national territory—New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Utah, and California—for which Mexico was indemnified $15 million. Signed on February 2, 1848, in the town of Guadalupe Hidalgo and thus bearing its name, the Treaty was negotiated under extreme duress. Mexico City was militarily occupied. President Polk let it be widely known that he had popular support to annex all of Mexico if necessary.

The Treaty consisted of 23 articles, most of which dealt with military logistics, prisoner exchange, property disposition, commercial rights, and arbitration procedures that would govern all subsequent disputes between the two countries. Article VIII gave Mexican citizens residing in conquered territory one year to leave. Those who remained would become American citizens and their "property of every kind...[acquired by]contract...shall be inviolably respected..." Article IX guaranteed that the ceded territories eventually would be incorporated into the U.S. Until that moment Mexican residents would enjoy American federal citizenship, "their liberty and property, and secured in the free exercise of their religion without restriction." Article XI recognized that because "a great part of the territories...are occupied by savage tribes," the U.S. vowed to police the Comanches and Apaches to curtail their raiding and sale of hostages, arms, and livestock on both sides of the border.

Article X stated, "All grants of land made by the Mexican Government or by the competent authorities...shall be respected as valid, to the same extent that the same grants would be valid, if the said territories had remained within the limits of Mexico." The U.S. Senate excised this article from the treaty precisely because it gave too much protection to Mexican land grants. The Mexican treaty negotiators understood that without this protection Mexicans in the ceded territories would quickly lose their land, which indeed they did, though at different speeds in California and New Mexico. The discovery of gold in California in 1849 hastened the process there. U.S. courts, usually based on flimsy justifications, failed to honor many of the land grants the Mexican government had awarded its citizens between 1821 and 1846. Those grants it did recognize were much reduced in size, stripped of the use of the commons that formed most grants, thereby guaranteeing that they would be inadequate for farming or ranching.

One of the persistent myths of American historiography has been that Mexicans happily greeted American soldiers as liberators, offered no overt resistance to military occupation, and allowed the conquest to occur without spilling a drop of blood. The facts attest otherwise. There was significant resistance in both California and New Mexico to American rule. In 1847, New Mexicans assassinated Charles Bent, the occupational governor imposed on them by the U.S. military. They fought vigorously and died valiantly in various theatres of the war. When they were eventually overpowered, they militarily resisted colonial domination and the dispossession of their lands through guerilla activity. Tiburcio Vásquez and Joaquín Murieta in California are but two of the men disparaged by the American press simply as "bandits." In New Mexico those resisting occupation banded secretly creating organization such as La Mano Negra and Las Gorras Blancas. They formed political parties, such as El Partido del Pueblo Unido, and joined anarchist and syndicalist groups. If Mexico's north is now remembered as having been easily conquered, it was because Comanches raids had so weakened the area's defenses and had so depleted its essential resources that locals were poorly animated and even less so equipped to mount a major defense.

The War of 1898

Having annexed half of Mexico in 1848, American foreign policy discussions naturally turned to Cuba, which the U.S. had coveted and repeatedly tried to purchase since colonial times. As the U.S. had warned in its 1854 Ostend Manifesto, no country would be allowed sovereignty over Cuba except Spain and if she persisted in her refusal to sell the island, the U.S. would take it by force: "The Union can never enjoy repose, nor possess reliable security as long as Cuba is not embraced within its boundaries."

The War of 1898 is often explained as the result of a number of national developments, most notably industrialization and extensive material progress, followed in 1893 by the most severe economic depression the country had then witnessed. Between 1803 and 1898, the U.S. saw massive geographic and demographic growth. The country was now continental in scope, with a score of colonized subjects, particularly in the West. The Indian threat had been eradicated through genocidal wars and forced confinement on reservations. Between 1870 and 1910, the U.S. absorbed 20 million immigrants. By 1898 many of them—the Chinese, Japanese, and Jews—were being increasingly denigrated as unworthy of national membership. This was a period of technological advances in transportation and communication, with many people abandoning subsistence agriculture in the countryside for wage labor in cities. Frequent labor unrest sought socialist solutions, while populists agitated against unbridled capitalist corporations and unregulated trusts. Indeed, it was in 1893 that historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared the American frontier closed. In the minds of elites and perhaps the popular masses as well, America had reached its limits at precisely the moment other empires were scrambling to claim one-quarter of the globe as their colonies. If American dynamism and economic vitality were to be maintained, new lands had to be conquered.

The territorial spoils of the War of 1898 were Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island. It was really Cuba, however, that the U.S. most coveted because of its proximity, its strategic location, its natural resources, and because of the extensive investments Americans already had in the island. Cuba was a paradise for agricultural production, abundantly yielding sugar and its by-products, molasses, and rum. Since the cultivation and processing of sugar cane was undertaken mostly by free blacks and African slaves, by the early 19th century planters in the American South began militantly promoting Cuba's annexation, fearing that black insurgency there might infect the mainland with racial war, as it had in Haiti in 1791. Cuba was slavery's last haven in Spain's empire, not abolished until 1884. After Barcelona, Havana was Spain's second busiest port. After Mexico City and Lima, Havana was the third largest city in Spanish America in 1821 and one of its richest.

American interest in Cuba was expressed quite early and doggedly sustained. President Thomas Jefferson sent agents to Cuba in 1805 with offers to purchase it from Spain. President James Monroe had his eye sharply focused on Cuba when in 1823 he forcefully announced the "Monroe Doctrine," warning European powers that any intervention in the Americas would be deemed an act of aggression that would provoke immediate U.S. response. At the end of the War of 1846, President Polk again offered to buy Cuba for $100 million; President Pierce upped the ante by $30 million but failed still.

The majority of Spain's colonies were independent by 1825. There had been a number of scattered attempts to gain Cuban and Filipino independence since the 1860s but all of them were easily foiled or rapidly faded. Finally, on February 24, 1895, a group of rebels in Cuba's Oriente province issued a call to arms—the Grito de Baire—against Spain, proved more successful. Led by José Martí, Máximo Gómez, and Antonio Maceo, with broad popular support from every sector of Cuban society, by August 1896, the insurgents had amassed a fighting force of some 50,000 widely distributed across the island. The Cuban rebels quickly mired Spain in a guerilla war in which she simply slogged along. War-weary, facing army mutinies, draft riots, and antiwar demonstrations at home, Spain was further weakened by the eruption of a second major independence movement in the Philippines in August of 1896. Since 1892, Filipinos had been secretly organizing an independence movement. Now it had broken out in armed rebellion, creating an autonomous government headed by Andrés Bonifacio.

Spain tried to blunt the Cuban independence movement on January 1, 1898, by conceding to political reforms and home rule. The rebels demanded complete independence. As Spain's soldiers mutinied and refused to fight, many of them wilting under the heat of the tropical sun, sickened by yellow fever and other diseases, it became clear to Cuban rebels and American observers that Spain had lost it will and ability to fight. Seeing a vulnerable Spain and unwilling to fathom an independent Cuba, the U.S. dispatched the warship Maine to Havana to protect American interests. On February 15, the ship exploded and sank, killing 266 sailors and wounding at least 100 more. To this day, the cause of the explosion remains unclear. At the time, the sinking was attributed to a Spanish mine. Quickly the calls for war against Spain intensified in the U.S. "Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain!" became an oft-shouted, frequently reprinted, jingoistic refrain.

The U.S. feared an independent Cuba largely because of racial anxieties. Cuba had an immense free black population that had grown enormously with emancipation in 1884. What would happen if the island nationalists won? Would this racially riven polity be able to establish a stable government? President McKinley's government thought not, refused to sell the Cuban insurgents arms, and consistently intercepted Free Cuba volunteers before they could set foot on the island. Stewart L. Woodford, McKinley's minister to Spain, summarized American worries and ambitions well when he stated, "I see nothing ahead except disorder, insecurity of persons, and destruction of property. The Spanish flag cannot give peace. The rebel flag cannot give peace. There is one power and one flag that can secure peace and compel peace. That power is the U.S. and that flag is our flag."

The spring of 1898 found the U.S. attempting to broker a peace with Spain, simultaneously asking the rebels to disarm and accept an armistice. Both refused. On April 11, President McKinley asked Congress for a declaration of war to subordinate Spain. The U.S. would enter the fray as a neutral broker, McKinley explained, who, at war's end, would become plenipotent over Spain's former possessions. The war declaration never mentioned the active struggles the Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Filipino independence movements were waging on the ground or the provisional governments they had established. Instead, McKinley emphasized, "Our trade has suffered, the capital invested by our citizens in Cuba has been largely lost, and the temper and forebearance of our people have been so seriously tried as to beget a perilous unrest among our citizens..."

Cuban rebels and their American Congressional supporters balked, finally approving a war resolution on April 25 only if it included the Teller Amendment in which the U.S. "disclaims any disposition or intention to exercise sovereignty... [and once Spanish rule is ended]to leave the government and control of the island to its people." As we will see shortly, this was a promise that would hauntingly constrain the U.S. when the war ended.

The War of 1898 was short. Hostilities began on May 1 when American naval forces steamed into Manila Bay in the Philippines, engaged Spain's naval forces, destroyed all of their ships, and within seven hours had silenced most of the fire from land batteries. That same day the major ports of Cuba were blockaded; on May 11 American ground troops invaded. By July 16, Spain's naval forces in Cuba surrendered. American forces then advanced to Puerto Rico and occupied it on July 26. Spain and the U.S. suspended hostilities on August 12, announced a general armistice, and on December 10, 1898, signed the Treaty of Paris ending the war.

The treaty was drafted entirely by Spanish and American representatives. No Filipinos, Cubans, or Puerto Ricans participated. For $20 million, Spain relinquished its claim and sovereignty over Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, a number of small Spanish-controlled Caribbean Islands, and part of the Samoan archipelago. Spain's Queen-Regent María Christina accepted the terms of the treaty noting bitterly that her country "resigns itself to the painful task of submitting to the law of the victor, however harsh it may be, and as Spain lacks the material means to defend the rights she believes hers, having recorded them, she accepts the only terms the U.S. offers her..."

The U.S. rapidly overwhelmed Spain's forces largely because in the 1880s America's military strategy had been reshaped from national to global in scope, shifting its focus from the defense of national borders and the protection of its merchants, to the creation of mobile, offensive forces that were variously embedded abroad in areas of import to the U.S. This required the construction of military bases on foreign soil, the creation of a "New Navy" with a large number of modern, steel battleships, and a highly trained military, which was accomplished by creating the Naval War College in 1884. When Spain battled the U.S. in 1898, it lacked such modern ships and had organized its navy to defeat internal insurrections in Cuba and the Philippines, but had not prepared itself for naval assaults from without or at sea. When these two highly unequal armadas and personnel met, Spain was easily outflanked.

Cuba was allowed to declare its own independence in 1902, but only after the American Congress saddled it with the 1901 Platt Amendment, which formally replaced the Teller Amendment. The Platt Amendment created a neocolonial relationship between the U.S. and Cuba whereby it striped Cuba of most of its sovereign powers and prohibited it from entering foreign treaties or assuming foreign debt. In addition, it required Cuba to cede territory to the U.S. in perpetuity for the Guantánamo naval base and grant the U.S. the right to intervene in Cuban affairs to guarantee "a government adequate for the protection of life, property and individual liberty." The Platt Amendment governed U.S.-Cuban relations until 1934.

Puerto Rico did not fare as well. Spain had always imagined it as one of its lesser colonies, as a minor military base in which it invested little but extracted all it could. Whereas Cuba prospered with the cultivation of sugar cane in the 19th century, Puerto Rico remained relatively stagnant and sparsely populated, without a major export crop. Its agriculture was devoted mainly to subsistence farming and coffee production, which were worked by relatively few African slaves, a majority white population (the largest of any of the major islands in the Caribbean), and a colored population that was mainly free.

Puerto Rico, like most of Spain's American colonies, briefly sought but failed to gain independence in the 1820s and 1830s. Another attempt was made on September 23, 1868, with the Grito de Lares, inspired by Ramón Betances, a French trained physician who had lived in exile most of his adult life. On that day over a thousand rebels declared the birth of the Republic of Puerto Rico, hoisted their flag, abolished slavery, and named a new town council for Lares. The movement failed rather rapidly, lacking popular support, composed as it was mostly of planter and merchant elites who wanted to end the economic grip Spanish merchants and large landholders held over the island. Such sentiments erupted in the 1880s, and again on the eve of American invasion. When Betances learned that the Americans were about to invade Puerto Rico on July 25, 1898, he urged his fellow countrymen to rise en masse, forcing the Americans to acknowledge a fait accompli. "It's extremely important," Betances wrote, "that when the first troops of the U.S. reach shore, they should be received by Puerto Rican troops, waving the flag of independence..." That did not occur. Instead, Spain granted Puerto Rico autonomy in November of 1898, several months after Spain and the U.S. had signed an armistice ending hostilities, but before a peace treaty had been ratified. Puerto Rico's independence was ever so brief.

For the U.S. the spoils of the War of 1898 were Cuba and the Philippines. Robert T. Hill, an American geologist who just before the war wrote a book on the West Indies noted that Puerto Rico was more unknown to the U.S. "than even Japan or Madagascar...The sum total of the scientific literature of the island since the days of Humboldt would hardly fill a page of this book." The American Congress debated what to do with Puerto Rico precisely because it was too small, too poor, too thinly populated, and for some, too racially dark to merit statehood. Its colored population in 1899 was 40 percent.

From October 18, 1898 to May 1, 1900, Puerto Rico was administered by the U.S. as a colony, ruled successively by three military governors: Maj. Gen. John R. Brooke, Maj. Gen. Guy V. Henry, and Brig. Gen. George W. Davis. Puerto Rico's elites, wearied by four centuries of Spanish exploitation, were hopeful that American rule would be a radical improvement, based as it was on ideals of democracy and progress. They soon learned otherwise. Puerto Rico was now an American colony and would remain so. One of the first acts Governor Brooke took was to rename the island Porto Rico, its official spelling until 1932.

The transition from military to civilian rule occurred on May 1, 1900, when the Foraker Act was put into effect, setting out the terms of the island's governance. Puerto Rico was declared an unincorporated territory. Neither the U.S. Constitution would apply nor would its residents be deemed American citizens. The island would be under the authority of a civilian governor, appointed by the President of the United States and approved by Congress. An Executive Council (Consejo Ejecutivo) would be similarly appointed to serve as the governor's cabinet and a 35-member House of Delegates (Cámara de Delegados) would be elected to two-year terms, but all of their decisions were subject to veto by the governor or Congress. Most other officials—”the attorney general, the treasurer, the court's justices, the commissioner of education—”would likewise be presidential appointees. The San Juan News on May 29, 1901 well captured Puerto Rican frustration, "We are and we are not an integral part of the U.S. We are and we are not a foreign country. We are and we are not citizens of the United States...The Constitution covers us and does not cover us...it applies to us and does not apply to us." Americans considered Puerto Ricans to be ill prepared for self-government, backward and uncivilized, and in need of paternal tutoring. Or, as Governor Henry stated in 1899, "I am...giving them kindergarten instruction in controlling themselves without allowing them too much liberty."

The Foraker Act was also an economic instrument of blunt force to advance American interests on the island and to thwart local ones. The act imposed a monetary system based on the dollar, devaluing the local peso, thus creating cheap access to land for sugar companies that would soon transform the island's exports to one. The native capitalist development Puerto Rico had established before 1898 in sugar, coffee and urban manufacturing, was quickly destroyed. Although the U.S. did invest in eradicating tropical diseases, in educating the population, and constructing an extensive system of roads, most of these infrastructural expenditures were undertaken to improve the climate for U.S. businesses, providing them with healthier workers, minimally educated consumers, and routes to export their goods.

The Foraker Act of 1901 was replaced by the Jones Act, Puerto Rico's Second Organic Act, on March 2, 1917. The new constitution's changes were minimal and mostly cosmetic, offering lexical changes in the island's governing bodies, calling for a higher proportion of Puerto Rican election to these, and finally declaring the island's residents as U.S. citizens. Jurisdiction over Puerto Rico remained in the hands of the U.S. Congress and Puerto Ricans ever since have demanded more autonomy, some have wanted statehood, and still others have maintained the dream of independence.

When Spain and the U.S. signed the Treaty of Paris ending the War of 1898, Filipinos resisted American occupation, declaring themselves independent on June 12, 1898. For the next forty-eight years, the Filipinos doggedly fought the American invaders. On July 4, 1946, the U.S. finally recognized an independent Republic of the Philippines. The treaty provisions in the Bell Trade Act were akin to those neocolonial strictures imposed on Cuba through the Platt Amendment. Filipinos were not allowed to make or trade any item that would compete with similar American products, nor could they nationalize natural resources in which U.S. citizens had ownership stakes. In addition, the U.S. was given sovereignty over its military bases in the Philippines in perpetuity.

Coda

In the 100 years between 1800 and 1900 the U.S. created two empires—one continental and one oceanic—utimately extinguishing the imperial ambitions once held by France, Spain, England, and the Comanches. The human and natural resources annexed by the continental empire augmented the U.S.'s industrial capitalist production. The oceanic empire was built by establishing sovereignty over a series of islands that assured the U.S. easy movement to global markets, with permanent military bases from which they could easily launch attacks. All of this was done and justified in the name of a God-chosen nation destined to greatness. If suffering occurred, if peoples had to be "removed," if innocents lost all of their possessions, so be it. It was the duty of a superior U.S. to uplift and civilize weaker savages. If they refused, noted an 1846 article in the Illinois State Register, then like "reptiles in the path of progressive democracy...they must either crawl or be crushed." Never mind what territorial rights of anteriority existed. Never mind what rules of international law existed. For as John O'Sullivan proclaimed in 1845: "Away, away with all these cobweb tissues of rights of discovery, exploitation, settlement, contiguity...The God of nature and of nations has marked it for our own; and with His blessing we will firmly maintain the incontestable rights He has given, and fearlessly perform the high duties He has imposed.

This, then, is a history of how residents of Spain, Mexico, Cuba, and Puerto Rico entered the U.S. through wars of territorial expansion during the 19th century. In the 20th century, both Mexico and Cuba would experience major social revolutions that would propel their citizens to the U.S. in search of liberty, refuge, and work. Puerto Ricans would make similar treks but as American citizens, seeking to better their lives on the mainland. And it was in the U.S. in the 1980s that these and other immigrants of Latin American origin coalesced politically as Latinos.

Ramón A. Gutiérrez, Ph.D., is the Preston & Sterling Morton Distinguished Service Professor in United States History and the College, University of Chicago. His field specialties include race and ethnicity in American Life, Chicano/Latino studies, Indian–White relations in the Americas, social and economic history of the Southwest, and Mexican Immigration. His major works include Mexican Home Altars, Contested Eden: California before the Gold Rush, and When Jesus Came the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1846. His 1993 article, "Community, Patriarchy and Individualism: The Politics of Chicano History" in the American Quarterly was awarded the Western History Association's Ray Allen Billington Prize. He received his Ph.D. in History from the University of Wisconsin.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Part of a series of articles titled American Latino/a Heritage Theme Study.

Last updated: December 9, 2015