Entrepreneurs from the Beginning: Latino Business & Commerce since the 16th Century

This American Latino Themes Study essay explores the growth of Latino business and commerce in the U.S. from the Spanish and Mexican colonial periods through the 20th and into the 21st centuries.

by Geraldo L. Cadava

For 500 years, from the earliest Spanish explorers to the growing league of 21st-century entrepreneurs, Latino business and commerce in the United States has encompassed the activities of ranchers, farmers, land colonizers, general store operators, street vendors, corporate executives, real estate developers, entertainment industry mavens, self-employed domestics, and barbers. They have run businesses small and large, with zero to thousands of employees, and have served Latino and non-Latino communities all around the world. Latino businesses at first concentrated in the southwestern portion of the U.S., as well as in Louisiana, Florida, and New York. By the 20th century, however, they had spread across the U.S. and beyond, as Latino culture, music, food, and styles became popular and widespread commodities. The Latino population in the U.S. increased from the late 19th century onward, leading to the expansion of Latino markets. Latino-owned and non-Latino businesses focused on cultivating as clients this growing group of consumers. Altogether, Latino business and commercial activities have constituted an important aspect of Latino ethnicity, politics, and community formation in the U.S.

The growth of Latino-owned enterprises, and of data collected by U.S. government agencies about them, has led to a wave of scholarship that has characterized Latino entrepreneurs as centrally important, though understudied, members of their communities. As a country, we have focused on the heated debates over Latin American labor migration, rather than the entrepreneurs who have created markets, played pivotal roles in the development of their communities, and emerged as political organizers and leaders.

Commemorating the long history of Latino business and commercial activities–through their designation as historically significant, or simply through greater awareness of them–poses several challenges. Such a process might entail the acknowledgment that already-recognized establishments, like the religious missions of the Spanish colonial period, had broader business and commercial significance. Alternatively, it could involve figuring out how to locate the precise sites of ephemeral activities. For example, how would one go about recognizing as historically important the street corners and parking lots where self-employed day laborers gather to find work? Even more broadly, designating such sites, since many of those who gather at them are not U.S. citizens, would require the recognition that non-citizens are capable of productive economic activity that is historically significant. Likewise, even though Latino entrepreneurship often has involved temporary activities or extremely small operations, only long-lasting and larger businesses have received recognition for their historical significance. Finally, how would one go about claiming the historical significance of businesses started by return migrants who saved money in the U.S. and learned successful business practices here, which enabled them to engage in entrepreneurial activities in their Latin American home countries? While these issues pose certain challenges to the project of designating historically significant Latino business and commercial activities, finding ways to recognize appropriately those endeavors would promote a richer understanding of the role Latinos have played in the history of American business and economics.

The establishment and growth of Latino business and commerce has mirrored the expansion of the Latino population itself. Until the late 19th century, the vast majority of such activities took place among Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the U.S. Southwest, the area of the U.S. that, until after the U.S.-Mexico War (1848) and the Gadsden Purchase (1854), formed part of the Spanish empire and Mexico. Other Latin American merchants conducted business during this period elsewhere in the U.S., in places like Louisiana, Florida, and New York. For the most part their stay in these places was temporary, and their dealings did not contribute to the formation, settlement, or advancement of Latino communities. Rather, they were confined to trading and other mercantile activities. Then during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the immigration of Latinos to the U.S. and their exile from international conflicts including Latin American independence movements, the Spanish-American War, and the Mexican Revolution, led to the growth and diversification of Latino businesses including groceries, clothiers, and medical practices that served these new communities. By the end of World War II, Latino business and commerce had spread across the U.S., from Los Angeles to New York, and from Chicago to Miami.

While the incorporation of Latino business and commercial activities into broader social, political, and economic patterns of the U.S. increased after World War II, most Latino businesses still catered primarily to Latino communities. Then from 1965 forward–after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (The Hart-Celler Act), the Cuban Revolution of 1959, and violent, anti-democratic repressions in Central and South American countries during the 1970s and 1980s led to the dramatic increase of U.S. Latino populations–Latino business and commerce exploded, becoming the fastest growing sector of the U.S. small business community. Most Latino businesses still served local Latino communities, but others reached broader non-Latino communities across the U.S. By the late 20th century, thousands of businesses opened by recent Latin American immigrants joined those opened by earlier generations of Latinos in the U.S., and many immigrants eventually returned to their home countries to establish businesses there. Their activities represented the hemispheric and global reach of Latino business and commerce during the 21st century.

The Economies of Northern New Spain

From its very beginning, Spanish imperial expansion in the Americas was a business venture. Spaniards mapped the land and exploited the indigenous labor that made it productive. They also extracted minerals that they sent back to the crown, which increased their own wealth as well. From Florida to California, they established missions and ranches that became extremely profitable, as Spanish missionaries, soldiers, ordinary citizens, and indigenous peoples raised cattle and crops, and then sold their meat, hides, tallow, grains, and vegetables both locally and throughout the empire. Among these men were the first Latino entrepreneurs.

Spaniards established cattle ranches as early as the 16th century, first near St. Augustine and Tallahassee, Florida. Tomás Menéndez Márquez owned the La Chua Ranch, which stretched thousands of square miles from the St. John's River in East Florida to the Gulf of Mexico, and produced more than a third of Florida's cattle during the 17th century. Márquez provided hides, dried meat, and tallow to Florida's Spanish colonies, as well as to Havana, demonstrating how Latino business and commercial activities reached distant markets from its earliest days. Once Márquez established his cattle business, he branched out into other commercial activities as well, traveling by boat to Havana and returning with goods that he traded in Florida.[1] Francisco Javier Sánchez became his successor, owning and operating stores, plantations, and ranches in Florida that supplied Spanish and British officials. Following paths first carved and traveled by indigenous communities, men like Márquez and Sánchez established some of Florida's earliest commercial trading routes, trading posts, and stores, much like other Spaniards did elsewhere across the Spanish empire's northern frontier.

If large-scale cattle ranching began in Florida, it became iconic in the Southwest. Juan de Oñate introduced cattle in New Mexico during the late 16th century; Captain Alonso de León and Eusebio Francisco Kino introduced cattle to Texas and Arizona during the 17th century; and Junipero Serra and Juan Bautista de Anza introduced cattle to California during the 18th century. Across the Southwest, livestock industries supplied nascent agricultural and mining operations, producing tallow for candles, and hides for clothing, harnesses, and bags that carried mineral ores and water. Ranches throughout the region relied on the labor of indigenous populations, which herded cattle and sheep, slaughtered the animals, and made clothing and other goods from them. By the early 19th century, cattle from Spain's northern frontier were shipped to South America, leading to the rise of cattle industries there, and again demonstrating early connections among distant markets. The cattle industries of northern New Spain also spawned some of the frontier's first illicit economic enterprises, as cattle rustlers illegally drove cattle across imperial and national borders.

Opportunity and Consequence on Mexican and U.S. Frontiers

Throughout the Spanish Colonial period, land grants awarded by the Spanish crown provided the grounds for business and commercial activities. After 1821, when Mexico won independence from Spain, the Mexican government continued the practice of granting lands on the country's northern frontier, particularly through the secularization of mission lands that were converted into ranchlands. From the 1820s through the 1840s, the Mexican government issued hundreds of land grants, with parcels that ranged from 4,000 to 100,000 acres each. By the time of the U.S.-Mexico War, 800 ranchers owned more than eight million acres of land. Some entrepreneurs divided their land for distribution among colonists and their families, who were then able to grow crops and raised animals. Other entrepreneurs developed ranches, many of which remained in operation decades after the U.S.-Mexico War. In 1760, for example, Captain Blas María de la Garza Falcón received from the Spanish crown a 975,000-acre land grant in Texas, which he called Rancho Real de Santa Petronila. Much of it later became the King Ranch, which, at half a million acres, was the largest ranch in the U.S. In Arizona, Toribio Otero received a 400-acre land grant that his great grandson, Sabino Otero, the so-called "cattle King of Tubac," expanded to include lands from Tucson to the U.S.-Mexico border city of Nogales. While men received the majority of Spanish and Mexican land grants, some women became property owners as well, allowing them to achieve a measure of independence from patriarchal Mexican societies during the early 19th century.[2]

The Southwest's agricultural, ranching, and mineral goods reached markets via shipping and trading networks including the 900-mile long Santa Fe Trail and other routes connecting San Antonio with El Paso, and Tucson with the Mexican port town of Guaymas, Sonora. Through the mid-19th century, the bulk of profits earned by Mexican-owned businesses stemmed from this trade in agricultural, ranching, and mining products. These goods were sold in small general stores, by street vendors, and merchants who shipped them throughout the U.S. and Mexico. Such business ventures laid the groundwork for Latino business and commerce in later periods of American history, and cemented relationships that increasingly pulled northern Mexico into the economic orb of the U.S.[3]

During the mid-19th century, the U.S.-Mexico War and the annexation of Mexican land by the U.S. transformed the social, political, and economic conditions of Mexican business and commercial activities in the southwestern U.S. Mexican American ranchers remained some of the wealthiest and most powerful businessmen into the 1880s, when U.S. railroad companies came to control most of their vast landholdings. Famously, California landowners, including Pio Pico and Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, lost thousands of acres of land. In some cases railroad, mining, ranching, and agricultural interests purchased the land or it was claimed by squatters. In many cases, Mexican American ranchers, called Californios, offered up their land to pay lawyer's fees incurred as part of their effort to defend their properties against encroachment. In bitterly ironic ends to their lives and careers as wealthy and powerful landowners, some Californios died bankrupt. The expropriation of lands once owned by Mexican Americans facilitated the industrial growth of the U.S. Southwest, with devastating consequences for Mexican Americans of all class-backgrounds.[4]

The shift from Mexican to U.S. economic and political control negatively affected many Mexican Americans living in the Southwest, but a few individuals capitalized on the new national context to develop their own business empires. Brothers Bernabé and Jesús Robles took advantage of the federal Homestead Act of 1862, which offered western land for cheap to those who would make it productive, claiming two 160-acre parcels of land that eventually became Three Points Ranch in southern Arizona. Their cattle and land made them wealthy, enabling them to purchase additional landholdings that eventually totaled one million acres between Florence, Arizona, and the U.S.-Mexican border, an expanse of land 134 miles long from north to south. Bernabé Robles later diversified his businesses, investing in Tucson real estate and general stores that he left to his children.[5]

In addition to ranches, Mexican American entrepreneurs owned wagon-based freighting businesses that moved goods across the Southwest, and between the U.S. and Mexico. In 1856, Joaquin Quiroga established a business that hauled goods between Yuma and Tucson, Arizona, thus becoming a pioneer of the freighting industry. But by the 1870s, Tucson's Estevan Ochoa (1831-1888) operated a business–Tully, Ochoa & Company–that shipped goods east as far as St. Louis, Missouri, and south as far as Guaymas, Sonora. He later opened several mercantile businesses, small mining companies, and sheep ranches that depended on his freight company to market their goods beyond Tucson. Freighting companies like Tully, Ochoa & Company generally went out of business after the arrival of railroads, which could carry goods farther, faster, and for less money, though several others remained competitive by operating routes not serviced by trains.

Business and Commerce in Urbanizing Latino Communities and Beyond

While vast ranchlands and transportation industries provided the foundations of Mexican American entrepreneurship into the late 19th century, with their decline, many Mexican Americans moved into the growing cities of the Southwest, including San Francisco, Los Angeles, Tucson, El Paso, Denver, Albuquerque, and San Antonio. White settlers arrived in these burgeoning metropolises as well, and within a couple of decades played an increasingly dominant role in the social, political, and economic histories of these places. As the influence and status of Mexican Americans waned, they increasingly became seen as members of a regional working class, and the vast majority of them lived substantially segregated lives within barrios. These neighborhoods became the strongholds of Mexican American business and commerce. Tucson's Federico Ronstadt, an immigrant from Sonora, established the city's biggest carriage-building business, as well as a successful hardware store. Leopoldo Carrillo, also from Tucson, became one of the city's largest real estate holders. According to the 1870 census, he was Tucson's wealthiest individual, owning almost 100 homes, ice cream parlors, saloons, and the city's first bowling alley. Because of the impressive array of his business interests, the Tucson City Directory simply called him a "capitalist." While Mexican entrepreneurs in these communities marketed their goods locally, they also developed commerce between the United States and Latin America. As part of his carriage business and hardware store in Tucson, for example, Ronstadt kept agents south of the border in Cananea, Nogales, Hermosillo, and Guaymas, Sonora.[6]

Emerging Latino communities elsewhere in the U.S., especially Florida and New York, also demonstrated vibrant patterns of trade between the United States and Latin America. Cubans and Puerto Ricans first settled in Tampa and New York City as exiles from Latin America's wars for independence against Spain. They formed some of the first Caribbean Latino communities in the U.S., and opened a diverse array of businesses shortly after their arrival. By the late 19th century, Caribbean merchants had traded in U.S. ports for more than a hundred years, but they did not establish communities. From the 1880s forward, though, Cuban and Puerto Rican exiles increasingly settled in southern and eastern U.S. cities.

Most famously, Cuban émigrés established cigar factories outside of Tampa. Caribbean revolutions had disrupted the business of these factories in Cuba. Furthermore, high import taxes on cigars entering the U.S. had curtailed their sales, a problem solved by opening cigar factories on the mainland. Vicente Martínez Ybor was the most famous proprietor of these cigar factories. Ybor and his partner Ignacio Haya created a company town – later known as Ybor City – with mutual aid societies, theaters, schools, and printing presses that grew up around the factories, which led to the rapid growth of the area as a whole.[7]

A leader of the independence movement, the Cuban exile José Martí moved between Florida and New York during the 1880s and early 1890s, and in those places became a unifying force for Caribbean Latino communities. Sotero Figueroa, a Puerto Rican exile who moved to New York City in 1889, developed a close friendship with Martí. He opened the print shop Imprenta América, from which he published several Spanish-language newspapers, including El Americano (The American) and El Porvenir (The Future). His press also printed Martí's paper, Patria (Nation). He moved to Cuba after the Spanish-American War, and eventually became director of La Gaceta Oficial, the newspaper of the new Cuban government. In addition to Figueroa's print shops, other Latino businesses located in New York as well, including small grocery stores, restaurants, and health centers like the Midwife Clinic of Havana in New York City, owned and operated by the Cuban woman Gertrudis Heredia de Serra. These businesses in the urban Southwest, Florida, and New York laid the foundations of Latino business and commerce during the early 20th century, when the U.S. Latino population increased in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, and during the Mexican Revolution.

During the late 19th and early 20th century, wars and revolutions throughout Latin America caused Mexican, Cuban, and Puerto Rican migrants to seek new livelihoods in the U.S. Production demands in mining and agricultural industries during the World War I era held forth the promise of jobs upon arrival. Latinos settled in cities like Los Angeles, Phoenix, Tucson, El Paso, Chicago, Detroit, Miami, and New York, generally in barrios established during the late 19th century.

After the Mexican Revolution, following a decade of migration and settlement, the economist Paul Taylor and the sociologists Manuel Gamio and Emory Bogardus conducted some of the first studies of Mexican communities in the U.S., which offered brief references to the Mexican entrepreneurs who met the needs of their growing communities. While a few owned land and operated their own agricultural businesses, many recent Mexican immigrants joined more established community members in opening small businesses, such as bakeries, barber shops, billiards halls, and pharmacies, as well as larger ones, like Mexican cinemas, hotels, and printing shops. Taylor concluded that, despite these ventures, by the end of the 1920s Mexican business owners had not, for the most part, advanced economically in the U.S.[8]

The growth of Latino communities created new markets for goods, services, and information, which led many Latinos–longtime community members and immigrants alike–to open businesses in barrios that remained segregated from other areas of the city and served a primarily Latino clientele. Only a few non-Latino businesses during the early 20th century sought Latino patronage, or stocked goods that Latinos desired. Doctors in Los Angeles, for example, like the "Doctora" Augusta Stone, or Dr. Chee, the "Doctor Chino," claimed to speak Spanish and advertised their services to Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. Nevertheless, the segregation of Latino communities created business opportunities for aspiring Latino entrepreneurs.[9]

Most Latino-owned businesses were small, family-owned operations that met the basic food, clothing, health, and everyday life (and death) needs of growing U.S. Latino communities. They included birthing and funeral services, tortilla factories, money transfer agencies, auto repair shops, bakeries, barbershops, and beauty salons. Demonstrating how Latino-owned businesses concentrated in barrios, the Mexican American neighborhoods of Corpus Christi, Texas, were home to stores named Loa's Shoe Shop, Juán González Funeral Home, Estrada Motor Sales, and La Farmácia Gómez, while those in Los Angeles were home to stores like Farmácia Hidalgo and Farmácia Ruíz. In addition, several Latinos were self-employed as lawyers, doctors, and dentists, even though their numbers paled in comparison to their white counterparts. Only rarely did Latino-owned businesses operate outside of Latino ethnic enclaves, or serve broader, non-Latino communities. Jácome's Department Store and Federico Ronstadt's hardware and general store–both established during the late 19th century and located in Tucson's central business district–served a mixed clientele including Mexican Americans, Native Americans, and white settlers who moved to the city in growing numbers from the 1880s forward.[10]

While most Latino businesses met basic needs, others that created cultural and leisure opportunities also increased during the early 20th century. For example, in 1927, Rafael and Victoria Hernández, a husband and wife who migrated to New York from Puerto Rico, opened Almacenes Hernández, which is widely regarded as the first Puerto Rican-owned record store in New York. Later during the 20th century, under new ownership, the store's name changed to Casa Amadeo, and in 2001 was listed in the National Register of Historic Places for its role in the development of New York's Latin American music scene. Musicians looking for work gathered at the store; Victor and Columbia records relied on the storeowners to help them locate new talent and keep them abreast of new trends; and, more generally, the store kept New York's Latino communities in tune with music from their home country. Similar stores served Latino communities elsewhere in the U.S., such as the Repertorio Musical Mexicana in Los Angeles, owned by Mexican immigrant Mauricio Calderón, who claimed that his store was "the only Mexican house of Mexican music for Mexicans."[11]

In addition to record stores and other music industries, Latino-owned cultural and leisure enterprises including restaurants, dancehalls, theaters, vaudeville houses, movie houses, bars, and cafes catered to Latino communities across the country. El Progreso Restaurant in Los Angeles enticed Mexican American customers with food prepared in a "truly Mexican style," and theaters like Teatro Novel and Teatro Hidalgo entertained Mexican immigrants with live entertainment and films imported from Mexico. Such Latino-owned businesses often shaped the social and political relationships of their owners, who became important community leaders. For example, as the owner of Club Sofía, a popular nightclub in Corpus Christi during the 1940s, Sofía Rodríguez gained a seat on the Texas Alcohol Beverage Commission, which put her in contact with politicians who expected her to deliver Mexican American votes. Other businesses also developed political inroads among Latinos by making financial contributions to Latino civil rights and social organizations like the Alianza Hispano Americana (AHA), founded in Tucson in 1894, or the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), founded in Corpus Christi in 1929.[12]

The growth of Latino businesses during the early 20th century therefore demonstrated the role of Latinos not only as economic and cultural consumers, but also as engaged social and political actors. They fought anti–Latino discrimination, debated the merits of candidates for office, and organized various community events. The immigrants among them also followed from afar the politics of their home countries, takings sides, for example, in the wars and revolutions that reshaped Latin American societies. Latinos formed several new social, political, and economic groups to engage these local and international issues, such as the AHA, LULAC, and their women auxiliaries. Latino–owned businesses, especially Spanish–language newspapers and radio stations, both shaped and reflected the activities of these groups.

Print shops were some of the earliest Latino-owned businesses in the U.S., dating back to the late 18th century, but a growing number of them were established during the early 20th century as a result of expanded Latino communities that demanded news both from their new cities and from their Latin American homelands. Several Spanish-language newspapers founded between 1910 and 1930 kept Latino communities informed, such as Ignacio Lozano's San Antonio paper, La Prensa, his Los Angeles paper, La Opinion, and Arturo Moreno's Tucson paper, El Tucsonense. Lozano shipped La Prensa to the West and the Midwest, making it something like a national Spanish-language daily. He used the profits from his newspapers to diversify his businesses, which eventually included a publishing company, a bookstore in Los Angeles called Librería Lozano, and real estate holdings throughout the city. Moreover, printing presses like Lozano's were precursors to Spanish-language radio and television media pioneered by individuals like San Antonio's Raoul Cortez and Tucson's Ernesto Portillo.

Expanding Populations, Expanding Markets

The children of Latin American migrants who arrived between 1900 and 1930 came of age in the U.S. during the mid-20th century. New waves of migrants joined them, compelled to leave their home countries because of poor economic conditions caused by the global depression of the 1930s, and because of civil wars aggravated by U.S. military interventions. World War II was a critical turning point for U.S. Latinos and Latin American migrants alike. Latinos joined the U.S. military and returned from service, articulating new claims to citizenship and belonging bolstered by Federal programs like the G.I. Bill. These new programs enabled many of the returning servicemen to pursue higher education, move out of barrios, and move into areas of their cities that were more affluent. Meanwhile, Mexican and Puerto Rican migrants met U.S. labor demands as participants in guest worker programs, and other Caribbean and Central American migrants–namely, Guatemalans, Cubans, and residents of the Dominican Republic–moved to the U.S. in increasing numbers. As during earlier periods, demographic changes within U.S. Latino communities led to new business and commercial practices.

Many Latino-owned businesses established during the late 19th and early 20th centuries continued to serve Latino communities into the late 20th century. Tampa's cigar factories operated into the 1950s; New York's Latino music and entertainment industries boomed between 1940 and 1970, eclipsing their success in earlier decades; and retail businesses like Jácome's Department Store remained open until 1980. These businesses relied on Latino clientele that had lived in the U.S. for a generation or more, and on trade with international markets throughout Latin America. Nevertheless, they also served new consumer markets in the U.S., including recent Latin American immigrants and non-Latino consumers increasingly interested in the goods and services provided by Latino-owned businesses.

Small businesses remained the cornerstone of Latino entrepreneurial activity into the post-World War II period, and Latino consumers were still their targeted clients. During a period generally defined as an economic boom time, second or third generation Latinos–descendants of Latino families that had lived in the U.S. since the 19th century or the children of Latin American immigrants who had arrived during the early 20th century–started more businesses than any previous generation of Latinos.[13]

Entertainment industries established during the early 20th century grew along with U.S. Latino communities. After the mass migration of Puerto Ricans to New York, the Forum Theater, which first opened its doors in 1917 to entertain Greek immigrant audiences, was renamed the Teatro Puerto Rico in 1948. Until the 1970s, the theater provided live entertainment for members of New York's Latino communities, including Puerto Rican musicians like José Feliciano, and Mexican actors like Mario "Cantinflas" Moreno, Jorge Negrete, and Pedro Infante. New York's Palmieri family opened a corner store in the Bronx known as the Mambo Candy Shop. It became a hangout for the city's Latino musicians. Eddie and Charlie Palmieri, whose parents owned the store, themselves became famous musicians. At the same time, a continent away, the Mexican American composer/musician Eduardo "Lalo" Guerrero entertained audiences in his Los Angeles nightclub, Lalo's.[14]

Latino-owned businesses during the mid-20th century increasingly found markets for their goods and services beyond the Latino community, both because Latinos began to move out of barrios after World War II, and because of the increasing commoditization of all things Latino, especially food and music. Goya Foods, for example, began in 1936 as a small, family-owned business that marketed its goods only within New York's Latino communities. Into the postwar period, non-Latino-owned chains including Safeway refused to sell Goya products. But under the leadership of Joseph A. Unanue, the U.S.-born son of Puerto Rican immigrant and company founder Prudencio Unanue, Goya Foods became the largest Latino-owned food distributor in the U.S., and also shipped its goods around the World, particularly to Latin America, Spain, and other European countries. La Preferida, a Mexican-owned food company established in Chicago during the late 19th century, also started as a small enterprise that then expanded to market its products nationally and internationally.[15]

New groups of Latin American migrants reinvigorated Latino business and commercial activities during the mid-20th century. Guatemalans fled their home country after the 1954 coup d'état that replaced the leftist leader Jacobo árbenz Guzmán with the U.S.-backed, conservative military leader Carlos Castillo Armas. Residents of the Dominican Republic fled their home country following the 1961 assassination of Rafael Trujillo, which unleashed more than a decade of social, political, and economic instability. Cubans fled their island following the Cuban Revolution through which Fidel Castro claimed power. As they settled in the U.S., these new groups of Latino migrants opened businesses that served their migrant communities, including bodegas, restaurants, music clubs, and other operations.

Since the earliest years of their migration to New York, Illinois, and Florida, Cuban migrants–especially the first wave of exiles that arrived in the U.S. right after the Cuban Revolution, which was, in general, more educated and affluent compared with later waves–have been regarded as a particularly entrepreneurial group of Latinos. Because Castro had limited their ability to open businesses in Cuba, many entrepreneurs were eager to flee the island. But even more than the supposed entrepreneurial orientation of early Cuban migrants, the Cold War policies of the U.S. aided Cubans who aspired to pursue careers in business, offering them financial aid, scholarships, and business loans. The concentration of Cubans in Miami also facilitated what one scholar has called "the development of ethnic-based social capital," or "economic and social resources and support based on group affiliation."During the 1960s, Miami quickly became the hub of Cuban American business activity, especially the neighborhood that became known as Little Havana. Restaurants, clothing stores, pharmacies, fruit stands, cafes, medical centers, and service-oriented businesses like locksmiths defined the business landscape of Miami's largest Cuban neighborhood.[16]

Business Booms and the Globalization of Latino Culture

As the U.S. Latino population expanded dramatically after 1965, so did the number of Latino-owned businesses. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act replaced national origins quotas with a visa-granting system that extended opportunities for settlement to migrants from previously restricted countries, yet continued to limit their number. Because the approximately 100,000 available visas numbered less than the millions of migrants who sought work in the U.S., an increasing number of migrants, particularly from Latin America, Asia, and Africa, entered the U.S. without documentation from the late 1960s forward. During the 1970s and 1980s, streams of Central American refugees from Civil Wars in Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador also settled in the U.S. Latinos from all ethnic backgrounds, especially from the 1990s onward, settled across the U.S., most rapidly in the U.S. South, Northeast, and Great Plains. The overall growth of the Latino population during the late 19th century provided opportunities for profit both for longtime Latino business owners, and for new migrant entrepreneurs.

As Latino business and commercial activities increased, the U.S. government paid increasing attention to U.S. Latinos as consumers and entrepreneurs. In 1972, the U.S. government published its first Survey of Minority-Owned Business Enterprises, and then repeated this exercise every few years, in 1982, 1987, 1992, 1997, 2002, and 2007. The 1972 survey revealed that there were approximately 81,000 Mexican-owned businesses in the U.S. By 1987, the number of Mexican-owned businesses had jumped by almost 230 percent, to 267,000. The 1992 survey, because the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act had led many Latin American migrants to regularize their citizenship status, revealed another dramatic increase in Mexican business ownership, as the number of Mexican-owned businesses grew by 42 percent, to 379,000. A decade later, in 2002, there were more than 700,000 Mexican-owned businesses in the U.S. The increase in business ownership was as dramatic among other Latino groups as it was among Mexicans. In 1977, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 248,000 Latino-owned businesses, by 1987 there were 422,000, and by 1997 there were 1.2 million. By 2002, Latinos owned 1.6 million businesses, and their rate of business ownership was growing faster than the rate of ownership by any other ethnic or racial group in the U.S. Acknowledging the astounding growth of Latino business and commercial activities, the U.S. Hispanic Chamber of Commerce was established in 1979 to represent the Latino business community.[17]

The geographic distribution of Latino owned businesses followed the residence patterns of U.S. Latino populations as a whole. Most Mexican-owned businesses were in the U.S. Southwest, though their number had grown in other areas as well, like the U.S. South, New York, and Illinois. In 1997, California and Texas alone were home to 75 percent of all Mexican-owned businesses. Meanwhile, 70 percent of Cuban-owned businesses were located in Florida; most Puerto Rican-owned businesses were in Florida, New York, and Illinois; and most businesses owned by individuals from the Dominican Republic were located in New York. After California, Texas, Florida, and New York, most other Latino-owned businesses could be found in New Jersey, Illinois, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Virginia. As Latino communities moved into suburbs, Latino-owned businesses quickly followed. For example, the Phoenix suburbs of Glendale and Mesa, which had few Latino residents in 1990, by the early 21st century were home to thriving butcheries, bakeries, tire shops, ice-cream stores, western wear outlets, and beauty salons. Their names often invoked the Mexican states of Sinaloa, Michoacan, Chihuahua, or Sonora. The stores displayed images of Emiliano Zapata or the Virgen de Guadalupe; hung advertisements for van rides to Mexico; wired money to Latin American countries; sold international phone cards, and newspapers from Mexican border cities. As such, they helped Latino immigrants maintain connections with their home countries, and served as primary points of entry into their new communities in the U.S. Nevertheless, despite the suburbanization of the U.S. Latino population, most Latino businesses located in cities, and five metropolitan areas alone–Los Angeles, Miami, New York City, Houston, and San Antonio–were home to more than a third of all Latino businesses in the U.S.[18]

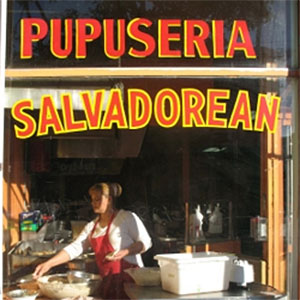

Into the 21st century, the vast majority of Latino-owned businesses were still small operations that served Latino communities across the U.S. Latino-owned restaurants, grocery stores, barber shops, movie houses, concert venues, publishing companies, and doctor's offices still catered to U.S. and foreign-born Latinos. They also operated small businesses that served non-Latino communities, such as landscaping and housecleaning services. Latino entrepreneurs tended to be younger than non-Latino entrepreneurs. Latino-owned businesses concentrated in the retail, service, and construction sectors of the U.S. economy. Most self-employed Latinos–those who claimed to run their own business–had no paid employees, and often relied on the unpaid labor of family members. Some held salaried positions, but also cleaned houses, did yard work, maintenance work, or sold baked goods like sweet bread, burritos, or tamales in their neighborhoods or at their places of employment. Sometimes Latinos borrowed money from family members, joined groups that pooled their resources, or successfully procured small business loans that enabled them to convert these side businesses into more profitable, full-time occupations.[19]

Nevertheless, despite these general trends, many differences existed among Latino business owners from different ethnic, class, and gender backgrounds. While Mexicans owned more businesses than any other Latino group, businesses owned by Cubans were, in general, more profitable. Stereotypes held by Latinos and non-Latinos alike said that Cubans were the most entrepreneurially successful of all Latino groups, or, conversely, that Mexicans lack business savvy. In fact, differences resulted from the historical circumstances that would-be Mexican and Cuban entrepreneurs have encountered in the U.S.; namely, that the anti-Castro policies of the U.S. have resulted in greater opportunities for Cubans. While all Latinos had difficulty securing bank loans to finance startup costs, and therefore had to rely on personal savings, small loans from family members, government programs, or high-interest loans from banks that exploited ethnic communities, aspiring Latino business owners from middle class backgrounds fared better than poor Latinos and recent immigrants. Their higher levels of education, wealthier relatives, and greater familiarity with U.S. business practices tended to give Cuban immigrants an advantage over these others.

Additionally, Latinos of particular ethnic backgrounds tended to loan money only to Latinos from similar backgrounds. When they opened their businesses, 18 percent of Latinos relied on "co-ethnic" sources of capital (i.e., Cuban, Mexican, or Nicaraguan), and only 6 percent benefited from "co-racial" capital (i.e., Latino). Likewise, Mexicans were more likely to shop at stores owned by other Mexicans, Cubans at stores owned by Cubans, and Puerto Ricans at stores owned by Puerto Ricans. Lastly, the number of Latina-owned businesses has increased faster than all other Latino-owned businesses. Nevertheless, Latina business owners have even less access to bank financing than their male counterparts, their businesses tend to be less profitable, and they concentrate disproportionately in food industries and domestic services.[20]

Differences among Latino entrepreneurs have resulted in highly segmented Latino business and commercial activities. In short, larger Latino-owned businesses have fared better than the small, primarily sole proprietor operations that constitute the vast majority of Latino-owned companies. Only 6.5 percent of Latino-owned businesses were large corporations, but these accounted for 40 percent of the total revenues of all Latino-owned businesses. Meanwhile, 85 percent of Latino-owned businesses were sole proprietorships, but these firms accounted for only 22 percent of total sales income.

The rise of Latino business and commerce has created opportunities for a few Latino entrepreneurs to become some of the most successful business leaders of the U.S. Roberto Goizueta served as the CEO of the Coca Cola Company for almost two decades. Arturo Moreno, owner of the Los Angeles Angels baseball team, and son of the Mexican American owner of Tucson's Spanish-language newspaper, El Tucsonense, became the first Latino to own a major U.S. sports franchise. Angel Ramos founded Telemundo, the first television station in Puerto Rico, which eventually moved to the Miami suburb of Hialeah and became the second largest Spanish-language network in the U.S.

Most Latino entrepreneurs experienced vastly different career trajectories. Surveys of Latino business owners revealed that many of them earned less than Latinos who worked in low wage, salaried positions. These business owners maintained their businesses only in order to remain autonomous from discriminatory labor markets, despite their lack of financial success. Furthermore, many Latino entrepreneurs who achieved financial success were financially successful only in relation to other Latinos, not in relation to white entrepreneurs. In general, Latino-owned businesses earned less than white-owned businesses. By the end of the 20th century, 21 million U.S. companies generated greater than $18 trillion dollars in revenues, or almost $900,000 dollars per company. 1.2 million Latino-owned businesses, however, generated sales of $187 billion, or only $155,000 per company. Meanwhile, 40 percent of Latino-owned businesses had annual revenue of $10,000 or less. Latino-owned businesses, therefore, accounted for almost six percent of all U.S. businesses, but only one percent of sales revenues. Moreover, comparatively few Latino entrepreneurs were included at the highest levels of corporate management. During the late 1990s, the magazine Hispanic Business revealed that there were only 217 executives at 118 Fortune 1,000 companies. In 2002, the number had risen to 928 executives at 162 Fortune 1,000 companies, still an extremely small number.[21]

Despite different economic outcomes among Latino entrepreneurs, and between Latino and white entrepreneurs, Texas A&M sociologist Zulema Valdez has found that all Latino entrepreneurs share a "universal belief in their success."Their claims to success in some cases were linked to financial earnings, but in many instances they stemmed from the fact that, by establishing their own business, they were able to leave behind "dirty, dangerous, or difficult" jobs, or jobs where they experienced "anti-immigrant sentiment, or racial or ethnic discrimination." Others defined success in non-economic terms, particularly women and recent immigrants who cited their mere survival, or their ability to help others.[22]

Their universal belief in success through business ownership, despite unequal levels of economic success, highlights a central paradox in the history of Latino business and commerce, and Latino history more broadly. Namely, Latino entrepreneurs, like many Latinos in general, continue to believe that progress and better lives are possible in the U.S. This is why many of the immigrants among them have taken great risks to leave their home countries for the U.S., and continue to build lives in the U.S. even though they have experienced discrimination and economic inequalities here. In fact, many Latino migrants increasingly question this wisdom, saving only enough money in the U.S. to establish businesses in their Latin American home countries. Official recognition of Latino business and commercial activities, through their designation as historically significant, will acknowledge this paradox that has been central not only to Latino history, but U.S. history more broadly. It will acknowledge the many ways that Latinos and others have found success in the U.S., but also the structural inequalities that continue to prevent it from being the best country that it can be.

Geraldo Cadava, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of History and Latina/o Studies at Northwestern University where he specializes in the United States-Mexican border region and Latina and Latino populations in the United States. His forthcoming book, The Heat of Exchange: Latinos and Migration in the Making of a Sunbelt Borderland, addresses the rise of cultural and commercial exchanges between Arizona and Sonora as a result of World War II. His next two projects will be about Latino conservatism and the construction of the U.S.-Mexico border. He received his Ph.D. in History from Yale University.

Endnotes

[1] Amy Bushnell, "The Menéndez Márquez Cattle Barony at La Chua and the Determinants of Economic Expansion in Seventeenth-Century Florida," The Florida Historical Quarterly 56, no. 4 (April 1978): 411.

[2] On the King Ranch, see David Montejano, Anglos and Mexians in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987), 79. On Toribio and Sabino Otero, see Thomas E. Sheridan, Los Tucsonenses: The Mexican Community in Tucson, 1854-1941 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1986), 52-53; and Miroslava Chávez-García, Negotiating Conquest: Gender and Power in California (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2004), 52-85.

[3] Andrés Reséndez, Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 93-123.

[4] Leonard Pitt, Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californias, with a Foreword by Ramón A. Gutiérrez (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 83-103.

[5] Sheridan, Los Tucsonenses, 97.

[6] Thomas E. Sheridan, Arizona: A History, Revised Edition (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012), 114.

[7] On Florida's cigar industry in general, see Gary Mormino and George Pozzetta, The Immigrant World of Ybor City: Italians and their Latin Neighbors in Tampa, 1885-1985 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998); and Nancy A. Hewitt, Southern Discomfort: Women's Activism in Tampa, Florida, 1880s-1920s (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 21-37.

[8] Paul S. Taylor, Mexican Labor in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, University of California publications in economics, 1930); Manuel Gamio, Mexican Immigration to the United States (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1930); and Empresarios migrantes mexicanos en Estados Unidos, eds. M. Basilia Valenzuela and Margarita Calleja Pinedo (Jalisco: Centro Universitario de Ciencias Económico Administrativas, Universidad de Guadalajara, 2009), 22-23.

[9] George J. Sánchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 176.

[10] Mary Ann Villarreal, "Life on the 'Hill': Entrepreneurial Strategies in 1940s Corpus Christi," in An American Story: Mexican American Entrepreneurship and Wealth Creation (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2009), 54; and Sánchez, Becoming Mexican American, 175.

[11] Calderón quoted in Sánchez, Becoming Mexican American, 175.

[12] Sánchez, Becoming Mexican American, 174-175; and Mary Ann Villarreal, "Life on the 'Hill': Entrepreneurial Strategies in 1940s Corpus Christi," 49.

[13] Empresarios migrantes mexicanos en Estados Unidos, 15.

[14] Roberta L. Singer and Elena Martínez, "A South Bronx Latin Music Tale," Centro Journal XVI, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 193.

[15] Empresarios migrantes mexicanos en Estados Unidos, 28.

[16] Zulema Valdez, The New Entrepreneurs: How Race, Class, and Gender Shape American Enterprise (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 25; María Cristina García, Havana USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959-1994 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); and Heike Alberts, "Geographic Boundaries of the Cuban Enclave Economy in Miami," in Landscapes of the Ethnic Economy, eds. David H. Kaplan and Wei Li (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.), 39, 41.

[17] Empresarios migrantes mexicanos en Estados Unidos, 8 and 25.

[18] Alex Oberle, "Latino Business Landscapes and the Hispanic Ethnic Economy," in Landscapes of the Ethnic Economy, eds. David H. Kaplan and Wei Li (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2006), 149, 154.

[19] Empresarios migrantes mexicanos en Estados Unidos, 26-27, 35, and 37.

[20] Wei Li, et al, "How Ethnic Banks Matter: Baking and Community/Economic Development in Los Angeles," in Landscapes of the Ethnic Economy, 113-114, and 125; and Valdez, The New Entrepreneurs, 25-26, 64, 69, and 89.

[21] Valdez, The New Entrepreneurs, 42-43.

[22] Ibid, 8, 44, 48, 97, and 99.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Part of a series of articles titled American Latino/a Heritage Theme Study.

Last updated: July 10, 2020