Last updated: December 15, 2024

Article

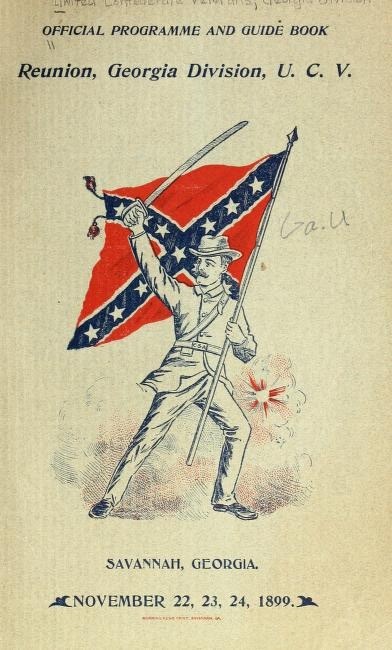

History of Memory, Tourism, and the Lost Cause at Fort Pulaski

Library of Congress

The Lost Cause Myth is the explanation of how Southern slave states that rebelled against the federal government justified succession. There are several components of the narrative that were created to protect former Confederates and their memory. First, was that the War was not about the institution of slavery, that Southern states seceded to protect their homes, property, and fought against an overbearing federal government. Second, that slavery was a benign institution that benefitted the enslaved and enslaver. Next, is that the Confederacy was only defeated because the United States had numerical advantage. Lastly, is Confederate soldiers and generals, such as Robert E. Lee, were heroes and martyrs, even though they fought to preserve the institution of slavery.

After the Civil War, white Southern women’s organizations led the efforts to honor their fallen soldiers and memorialize their deaths. Ladies Memorial Associations established Confederate cemeteries, designated April 26 as Confederate Memorial Day, held celebrations for Confederate veterans, and erected monuments. In Savannah, the local Ladies Memorial Association held events to celebrate Confederate veterans who served at Fort Pulaski. In the early 1890s, Georgia newspapers rediscovered the “Immortal 600,” a group of Confederates who were imprisoned at Fort Pulaski and casted them as heroes and martyrs. This renewed interest encouraged the former captives to share memories of their experiences at celebrations, in books, and in public speeches, developing a Confederate narrative of Fort Pulaski.

FOPU Archives

On September 11, 1894, Mrs. Anna Davenport Raines formed the Savannah Chapter of United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC). The UDC’s mission was all encompassing: honoring the Confederate dead, preserving historic Confederate sites, building Confederate monuments, helping Confederate veterans, and holding celebrations of all types. Yet, they were most impactful in education as they promoted a positive Confederate history of the Civil War. They also created the Children of Confederacy to encourage young people to memorialize the Confederacy and understand their Southern heritage.

In 1903, the Savannah Chapter of the UDC held several events to honor Confederate veterans. At one of these events, the organization presented a Confederate flag that was flown at Pulaski during the bombardment, to a few of the remaining veteran defenders. At other events, they read Colonel Olmstead’s letters, wartime accounts written by veterans, and organized a parade in Savannah. These celebrations strengthened the memory of the Confederacy’s former glory at Fort Pulaski and allowed the local white community to celebrate the fort and the men who defended it.

In 1934 Ralston B. Lattimore joined Fort Pulaski National Monument as an assistant historian and led the fort into a new era. As assistant historian, Lattimore was given carte blanche to create an interpretive program for Fort Pulaski which was the norm for all parks in the National Park Service. Lattimore turned to the experts in the field, the UDC, to prepare the park for its opening. In 1935, after a long correspondence with Lattimore, the UDC chose Fort Pulaski as the site for their annual state convention which brought hundreds of Daughters from across Georgia to the fort. Lattimore granted the UDC special permission to fly the Confederate battle flag for the first time in its history, birthing the fort’s new Confederate identity. During the Confederate occupation, only the national flag of the Confederacy had flown over the fort.

FOPU Archives

The relationship between Lattimore and the UDC was mutually beneficial. On one hand, the park benefited from the outreach and knowledge that the UDC provided. The chapter often organized excursions to the park bringing visitors, including large groups of the Children of the Confederacy. In addition, they gave Lattimore access to privately held collections that helped him frame the interpretation of the park. On the other hand, the UDC could hold celebrations honoring Confederate soldiers in the very site where they fought.

In 1938, the UDC consecrated the northwest corner of Fort Pulaski with a plaque honoring two Confederate soldiers who saved the national flag during the bombardment. They also petitioned the federal government asking the park service to use the words “The War Between the States,” instead of the “Civil War” to discuss the conflict. This, they argued, would send the message that war had been between two sovereign countries instead of a rebellion from the South. The information booklets given to visitors in 1940 used this phrase.

FOPU Archives

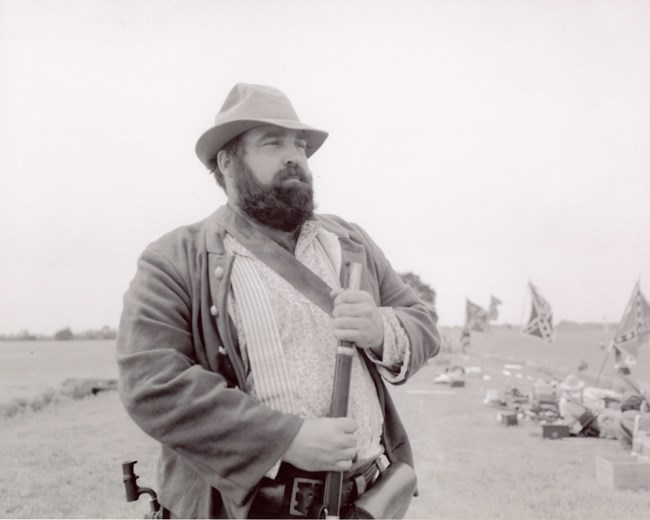

In 1961, Fort Pulaski National Monument celebrated yet another milestone: the one-hundred-year anniversary of the capture of the fort by the Georgia Militia. Reenacting the events of January 1861, members of the UDC and Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) marched into the fort to symbolize the capture. The fort was filled with a patriotic ambiance as the Savannah High School Band performed “Dixie” for the visitors. The UDC and SCV honored the soldiers stationed at Fort Pulaski by reading their letters. Several dignitaries attended the event with Savannah Mayor, Malcolm MacLean, offering remarks about the sacrifices of the Confederate soldiers.

In the 1980s and 1990s, events at the fort still focused primarily on its Confederate past and the narrative of the Lost Cause. The annual Confederate Nog Christmas Party reminded visitors of how Confederate soldiers celebrated Christmas in 1861. The interpretive video shown in the Visitor Center features the old language of “The War Between the States.” The Confederate National Flag was flown over the fort until the early 2000s and National Park employees still only wore the Confederate Grays when doing demonstrations. In the early 2000s, historical reenactments of the Immortal Six Hundred in 2007 showcased the sacrifices and celebrated the determination of Confederate soldiers demonstrated during the Civil War. In 2012, the UDC and SCV came back to the fort to commemorate the thirteen soldiers who had died as prisoners with a new monument.