Last updated: January 6, 2026

Article

Harriet Tubman and the 54th Massachusetts

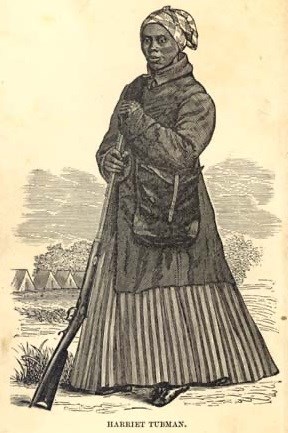

"Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman" by Sarah H. Bradford (Auburn, NY: W.J. Moses, 1869), frontispiece. Illustration by J.C. Darby.

Most Americans know Harriet Tubman as a woman who took great risks to help others emancipate themselves from enslavement. Relatively few know the entirety of her story, including her groundbreaking American Civil War service. Tubman first volunteered for duty shortly after the outbreak of hostilities in 1861, offering her services to Brigadier General Benjamin Butler at Fort Monroe in Virginia. As enslaved people rushed to sanctuary at the garrison, Tubman provided humanitarian aid as a cook, laundress, and nurse.[1]

While Tubman spent the winter of 1861-1862 in Boston, Massachusetts, Governor John A. Andrew recruited her for a new assignment, performing humanitarian work in Port Royal, South Carolina. In spring 1863, army leadership in South Carolina allowed Tubman to leave her nursing position and take on a role that aligned with her underground railroad experience. Tubman served on the front lines in South Carolina and led a scouting party of eight men. This group obtained key intelligence for the local army leadership in March of 1863, which led to US forces capturing Jacksonville, Florida.[2]

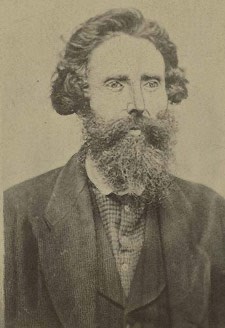

On June 2, 1863, Harriet Tubman executed the most notable achievement of her Civil War service, the Combahee River raid. She planned this operation alongside Colonel James Montgomery, who fought pro-slavery settlers alongside John Brown in the Bleeding Kansas conflict of the 1850s.[3] On Montgomery's orders, Tubman led a raiding party up the Combahee River to damage the economic power of the South by burning wealthy plantations and liberating the enslaved people held there. Tubman's talents for stealth and reconnaissance, honed during her years on the Underground Railroad, enabled the US boats to avoid Confederate mines and troops. During the raid, nearly 800 enslaved men, women, and children rushed to US forces—and to their freedom. The irrepressible surge to the boats represented one of the largest groups of enslaved people ever emancipated at one time.[4]

Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1863.

Carte de visite by Leonard & Martin, ca. 1858. Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society.

The next day, on June 3, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment landed in Beaufort, South Carolina.[5] Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the commander of the 54th, established a different working relationship with Montgomery than Tubman had. Shaw and Tubman had different ideas of what constituted acceptable warfare, and their reactions to Montgomery’s orders reflected that difference. Whereas Tubman enthusiastically led Montgomery's raid up the Combahee River, Shaw felt troubled when he received similar orders a week later. He and the 54th had accompanied Montgomery on his raid up the Altamaha River on June 10 and 11, 1863. Upon reaching Darien, Georgia—a small, staunchly Confederate town—Montgomery commandeered one company of the 54th Massachusetts and ordered them to assist him in sacking and burning the town.[6] After the raid, Shaw wrote to his wife,

Besides my own distaste for this barbarous sort of warfare, I am not sure that it will not harm very much the reputation of black troops and of those connected with them. For myself, I have gone through the war so far without dishonour, and I do not like to degenerate into a plunderer and robber…[7]

Northern press coverage soon confirmed Shaw's fears, as even the abolitionist newspaper The Commonwealth condemned the burning of Darien at the hands of "Yankee negro vandals" and "brigands."[8] While The Commonwealth had praised Tubman's Combahee River raid in previous weeks, the destruction of an entire town crossed a line.

Harriet Tubman first crossed paths with the 54th Massachusetts in June or July of 1863. Following the Combahee River raid, she slipped back into a more conventional role for a woman during the Civil War. She served meals to the men of the regiment, including, as she later claimed, Robert Gould Shaw's last meal.[9] He ate this final breakfast on July 18, 1863, the day the 54th Massachusetts launched a brave but doomed assault on the Confederate-held Fort Wagner. Tubman witnessed this battle, later describing it to historian Albert Bushnell Hart:

And then we saw the lightning, and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder, and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling, and that was the drops of blood falling; and when we came to get in the crops, it was dead men that we reaped.[10]

After the battle, while the survivors counted the devastating casualties, the wounded went to segregated field hospitals. Clara Barton greeted the White officers when they arrived at Hilton Head, while the Black rank and file returned to Beaufort and entered the care of Harriet Tubman.[11]

Tubman’s experiences with the 54th Massachusetts, and in the Civil War as a whole, influenced her life for decades to come. She struggled to receive recognition and compensation from the United States government for her wartime service. Her pension application, filed in 1897, claimed "three years services as nurse and cook in hospitals, and as commander of Several Men (Eight or nine) as scouts during the late War of the Rebellion."[12] Despite Harriet Tubman's role as the first American woman to lead a military action in wartime, Congress only recognized her work as a nurse when they granted her pension request.[13]

Boston Herald, May 31, 1905.

During a trip to Boston in 1905, Harriet Tubman visited the memorial dedicated to Robert Gould Shaw and the soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts. A journalist encountered her at the memorial and described how she "gazed long and tenderly on the magnificent work of the sculptor and dropped a silent tear for the departed dead."[14] The resulting article in the Boston Herald primarily emphasized Tubman’s safe, matronly role as "Shaw's nurse," who served the young colonel his last meal and healed his wounded soldiers. It briefly referenced her scouting work, but only described its objective as smuggling "medicines and other goodies" to US forces, ignoring her significant role in gathering military intelligence. The daring woman who led the Combahee River Raid a month and a half before the assault on Fort Wagner vanished from the story entirely.

Observers trimmed out or simplified the parts of Tubman's story they deemed inconvenient, leaving behind a version of her life that reflects little more than what they thought safe and comfortable. They emphasized her role as the gentle, nurturing "Mother Tubman," discarding the strong, assertive military and underground railroad operative that defied pro-slavery laws and challenged 19th century assumptions about the female sphere. Just one year after Tubman's death, Booker T. Washington:

celebrated her ‘law-abiding’ nature and asserted that her 'devotion to duty' was exemplary of 'the best types of our race,' in contrast to 'the criminal Negro' Washington made a point to disparage. However, such rhetorics insist that we remember Tubman by forgetting her.[15]

The process of remaking Harriet Tubman began early, even during her lifetime. She endures as a household name today, but only rarely do we glimpse the full picture.

Footnotes:

[1] Catherine Clinton, Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2004), eBook location 311.

[2] Clinton, eBook location 347.

[3] Brian Dirck, “By the Hand of God: James Montgomery and Redemptive Violence,” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 27 (Spring-Summer 2004): 101.

[4] Clinton, eBook location 349.

[5] Luis Fenollosa Emilio, History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865 (Boston: Boston Book Company, 1894), 36.

[6] Emilio, 41-43.

[7] Russell Duncan, ed., Blue-Eyed Soldier of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (Athens, GA: University of Georgia, 1992), 343.

[8] Clinton, eBook location 363.

[9] Clinton, eBook location 365-366.

[10] Clinton, eBook location 370.

[11] Clinton, eBook location 368.

[12] Harriet Tubman, General Affidavit, 1897, Government Form, from National Archives, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, http://archives.gov/legislative/features/claim-of-harriet-tubman (accessed July 23, 2020).

[13] U.S. Congress, House, A Bill Granting a Pension to Harriet Tubman Davis, Late a Nurse in the United States Army, HR 4982, 55th Cong., 3rd sess., amended January 19, 1899, http://archives.gov/legislative/features/claim-of-harriet-tubman (accessed July 23, 2020).

[14] “Shaw’s Nurse at Memorial,” Boston Herald, May 31, 1905.

[15] Vivian M. May, “Under-Theorized and Under-Taught: Re-examining Harriet Tubman’s Place in Women’s Studies,” Meridians 12, no. 2, Harriet Tubman: a Legacy of Resistance (2014): 38.