Part of a series of articles titled Fort Scott History.

Article

Fort Scott in the Civil War

Michelle Martin, Fort Scott NHS volunteer

On the heels of the turbulent "Bleeding Kansas" era which swept this region in the late 1850s lingered the shadow of civil war. In April of 1861, war between the Union and Confederacy was officially declared. The old frontier military post of Fort Scott had been abandoned for over eight years, and a town of the same name had grown in its place. With the advent of war, the U.S. Army returned and established a military headquarters in the town of Fort Scott.

As early as August of 1861, the Union Army occupied its former frontier hospital, the adjacent barracks and stables, and began construction on new warehouses, powder magazines, wells, a blacksmith shop, an icehouse, a military prison, and over 40 miles of fortifications around Fort Scott. As the site of a quartermaster supply depot and countless regimental camps, Fort Scott would become the largest and strongest Union post south of Fort Leavenworth.

Uncle Sam's Men

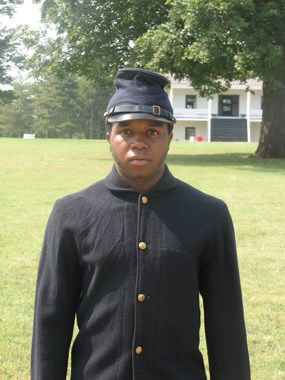

During the four years of war, soldiers from Wisconsin, Ohio, Iowa, Indiana, and Colorado passed through the streets of Fort Scott. Some regiments camped only temporarily at Fort Scott on their way to campaigns in Missouri, Arkansas, and the Indian Territory, while others were permanently stationed here to protect the area. Fort Scott also was home to several of its own regiments including the 2nd Kansas Light Artillery, the 6th Ks. Vol. Cavalry, and the 1st Ks. Colored Vol. Infantry. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Indian Home Guards, recruited primarily from displaced Indian refugees, could even be found among this sea of faces in town.

Quartermaster Supply Depot

Crucial to the success of the Union campaigns was the supply depot located at Fort Scott. The Quartermaster Department issued all rations, feed, horses, wagons, blankets, and equipment for troops camped within 40 miles of Fort Scott.

Confederate General Price dreamed of capturing the millions of dollars in supplies stored at the supply depot, and Price's dream realized certainly would have meant disaster to the Union. Rebel troops did pass 12 miles east and north of Fort Scott in both 1861 and 1864, but an attack never occurred. The constant guerrilla warfare remained the only challenge to the men positioned to defend Fort Scott's supplies.

Weary Hearts

Fort Scott's hospital was designated as a "General Hospital," an army classification given to larger medical facilities. It was filled with soldiers who suffered from disease or who sustained wounds in battles and skirmishes in Eastern Kansas and Western Missouri.

Large numbers of patients forced hospital personnel to utilize the former guardhouse, infantry barracks, and even tents as wards. A Hospital Aid Society consisting of concerned citizens attempted to help the overburdened hospital staff. Despite receiving care, not all the soldiers survived. Many died and were buried in the National Cemetery, two miles southeast of the hospital.

Military Prison

One of the buildings constructed by troops during the war was a two-story military prison. The Provost guards at Fort Scott were responsible for Confederate prisoners of war, suspected Southern sympathizers, unruly Union soldiers, and at times unlawful citizens of Fort Scott. The prison housed these men as they awaited their trials, served sentences, or passed the short days before their executions.

Haven for the Homeless

From the very start of the war, Fort Scott provided a safe harbor for refugees. In the beginning, families fleeing the warfare in Missouri poured into Kansas and Fort Scott. Later, thousands of homeless people passed through from Arkansas and the Indian Territory. These included hundreds of free Blacks, escaped slaves, Indians and pro-Union settlers. Often arriving with few possessions and settled in makeshift camps about town, the most destitute of these refugees received help from the Army and citizens of Fort Scott.

Hell's Headquarters

Behind the scenes of Fort Scott's military headquarters lies the less memorable picture of daily toil and pleasure. Snakes, mosquitoes, and days of drill and monotony left many soldiers cursing the war and camp. Soldiers' accounts detail their attempts to keep entertained with a game of baseball or cards, writing letters, a concert by the 9th Wisconsin Band, or perhaps even a dance organized with the ladies of town. And, of course, pay day often found many men seeking entertainment in Fort Scott's taverns and saloons.

The forced friendship between the town and the Army was at times strained. In September of 1861, Confederate troops passed east of Fort Scott, and the order was made for all troops and citizens to retreat north to Fort Lincoln on the Little Osage River. When Union soldiers who were left in town looted citizen's stores and homes, they did little to encourage amity. Relations were stirred again when two soldiers were accused of raping a young girl. Horrified and outraged, townspeople mobbed the prison and hung the soldiers before they ever reached trial.

From Pandemonium to Peace

After the Civil War ended in April of 1865, the U.S. Army remained at Fort Scott through the summer. By October, the Army had sold their buildings and military surplus at public auction, the hospital was closing down, and the last troops were marching home.

The town resumed a quieter pace, steadily growing as frontier America expanded until the next sweep of change brought by the great railroads left its imprint on Fort Scott's history.

Suggested Reading

- The American Indian in the Civil War, 1862-1865, Annie H. Abel.

- The Sable Arm, Dudley Taylor Cornish.

- Civil War Kansas: Reaping the Whirlwind, Albert Castel.

- Inside War, Michael Fellman.

Last updated: February 14, 2025