How a Small Group of Dedicated Citizens Changed the World

"Our inner being, which we call ourself, no eye nor touch of man or angel has ever pierced. ... Such is individual life. Who, I ask you, can take, dare take, on himself the rights, the duties, the responsibilities of another human soul?" from Solitude of Self, address delivered before the Committee of the Judiciary of the U.S. Congress by Mrs. Stanton, age 77, on January 18, 1892

NPS/Women's Rights National Historical Park

Women's Rights National Historical Park

Seneca Falls, New York

Social justice is the view that people deserve equal rights and opportunities. Although the term was not widely used in the nineteenth century, a small group of women in Seneca Falls, New York were keenly aware of its doctrine. Women's Rights National Historical Park commemorates the struggle of women for their equal rights. Because of its geography, the upstate New York region became of particular focus for social issues. Fertile lands and abundant water resources with important access routes to the west lured people to the area from parts of the eastern United States and western Europe. The communities of Seneca Falls and Waterloo were in the nucleus of socially important concerns.

NPS/Women's Rights National Historical Park

Previous discussions of social inequities had incorporated ideas about women’s rights, but the issue of equality for women was often subsumed within other movements. Women advocated on behalf of causes ranging from better living conditions for the poor to temperance, as well as other types of benevolent reform. Within these spheres, they confronted discrimination at various levels and debated the issue of their right to participate in politics, religion, activism, and public speaking.

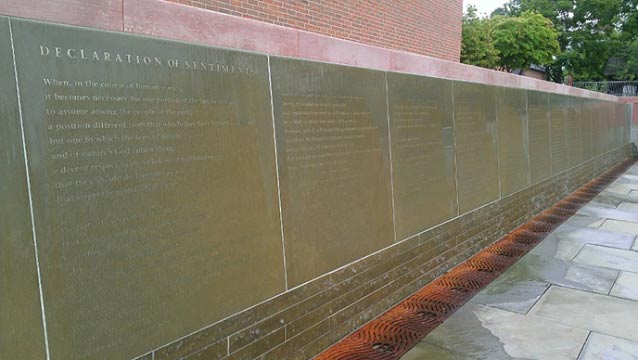

Stanton, Mott, Wright, M'Clintock, and Hunt organized the First Women’s Rights Convention, which was held on July 19 and 20, 1848 at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Seneca Falls. The presence of a strong reform sentiment in Waterloo and Seneca Falls and the surrounding area, combined with the national social and political context, enabled Stanton, Mott, Wright, M’Clintock, and Hunt, along with other supporters, to organize the event that became the cornerstone of a new Women's Rights Movement. The outcome of the convention was a document entitled The Declaration of Sentiments. Based on the Declaration of Independence, the Declaration of Sentiments stated the discriminations women experienced with a proposed agenda of actions on particular issues of discrimination. It was signed by sixty-eight women and thirty-two men.

NPS/Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation

The Elizabeth Cady Stanton House remains an icon in the advancement of women's rights and abolition—the movement to end slavery. The Stanton family lived in Seneca Falls from 1847 to 1862. Along with the house, the landscape was an important setting in Stanton's life, as it pertained to issues of child-rearing, domestic economy, and the role of women. Stanton’s father gave her the house, which had been uninhabited for many years. Accordingly, he also gave her money to put the house and grounds in order. Stanton set “gardeners to work” on the grounds, which comprised two acres that were “over grown with weeds.” By 1851, Stanton wrote to her sons at boarding school, "the house and grounds [are] in order."

Massachusetts Historical Society

Stanton followed the Graham diet of vegetables, fruits, whole wheat breads, and plain water. She grew raspberries, currants, grapes, quinces and canned the fruit from these plants. She also grew enough squash to assemble “thirteen squash pies” at a time. Stanton’s husband, Henry, grew fruit trees. In a letter to his wife's cousin, Gerrit Smith, Henry noted, “... I have gone somewhat largely into planting and grafting fruit trees."

In 1862, the Stanton family moved to Brooklyn, where Stanton continued her fight for women's rights. The Civil War interrupted the momentum of women's rights conventions. Women continued to agitate as a group for social reform, although the focus shifted from their own rights to abolition. In 1863, Stanton and others organized the Women's Loyal National League to send a petition to Congress in support of abolition signed by one million women. After the Civil War, the movement transformed to specifically emphasize woman suffrage. Her children grown, Stanton traveled and spoke throughout the country, advocating equal rights for women in all areas of life.

Stanton died in 1902, eighteen years before her greatest cause, woman’s suffrage, saw fruition. The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited any U.S. citizen from being denied the right to vote based on gender, was ratified in 1920.

The First Women's Rights Convention and Declaration of Sentiments have earned the village of Seneca Falls a place in the hearts of people locally and around the world. On Tuesday, November 6, 2012, Women’s Rights National Historical Park served as polling place for the voters of Seneca Falls, New York, District 2. Over 500 people exercised their right to vote in the park's Visitor Center. Superintendent Tammy Duchesne remarked, "I can think of nothing more appropriate, relevant, or inspiring."

While most philosophers agree that there is no completely just society, the pursuit of universal social justice is ongoing. Women's Rights National Historical Park preserves the historic sites and landscapes associated with the nation’s First Women’s Rights Convention to educate and inspire current and future generations to exercise their rights as citizens for the betterment of the world for themselves and others.

Visit this Park Landscape

NPS/Women's Rights National Historical Park

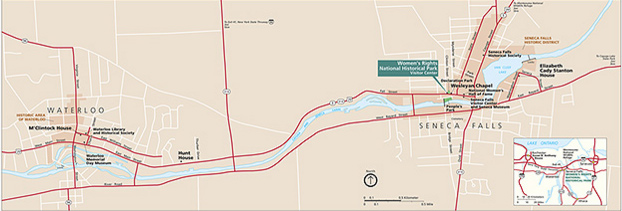

Some park buildings are open only during certain seasons of the year, and most are only open during guided tours. For the most comprehensive information, a larger map, and news and updates about the park, visit the Women's Rights National Historical Park website.

- Contact: (315) 568-2991

- Fees: All programs, tours, exhibits, and film are free

Access

- Visitor Center & Exhibits: 136 Fall Street, Seneca Falls

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton House: 32 Washington Street, Seneca Falls

- Wesleyan Chapel: 136 Fall Street, Seneca Falls

- M'Clintock House: 14 E. William Street, Waterloo

- Hunt House: 401 E. Main Street, Waterloo (interior not open to the public)

Guided Tours: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily

Last updated: August 18, 2020