NPS Photo

New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park

New Bedford, Massachussetts

When you contemplate the sounds of a national park, you might think of the whisper of the wind through the trees, the crunch of the trail underfoot, or birdsongs. Just as each park is different, the sounds of each park tell a different story.

In New Bedford, Massachusetts, the sounds of the city are not unlike many places across the U.S. And like many cities, they're easy to overlook. But with a little insight into the history of New Bedford, and when you actively listen, you may hear something very different.

NPS Photo/C. Beagan, 1997

Located on Buzzards Bay, along the southeastern coast of Massachusetts, New Bedford was the center of the nation’s whaling industry and home to America’s largest whaling fleet during its heyday in the 1860s. The thirteen downtown city blocks that comprise New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park are paved with history.

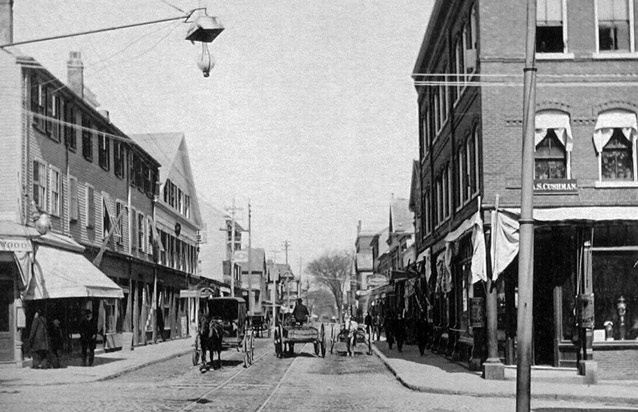

Today, we recognize the sounds of cars, trucks, and bikes across the largely cobblestone streets. In decades past, however, street sounds ranged from horse hooves on cobblestones and rolling wooden casks on granite runners to electric trolley cars and busses zipping along the city’s tracks.

The New Bedford street grid, designed by Joseph Russell and created more than two centuries ago, has undergone relatively minor changes in layout since its establishment. Narrow streets and short blocks attest to a pedestrian, pre-automotive era when city life centered on the nation’s busiest whaling port. Sounds still echo off nearby buildings as you walk along the narrow streets.

NPS, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park

Street paving, begun in the 1830s and completed within two decades, employed cobblestones. Granite curbing and flagstone sidewalks served largely pedestrian traffic, while granite runners spanned many intersections to facilitate moving large wooden casks from the harbor to processing centers in the area.

The introduction of horse-drawn street cars in 1872 required repaving sections of some streets along which tracks were laid. Belgian blocks replaced cobblestones between the trolley tracks on increasingly frequented streets, providing smoother, quieter rides for the new street car carriages. The granite Belgian blocks were originally used as ballast (weight for stability) on merchant ships returning to New Bedford from Belgium.

NPS Photo

In 1890, the clop of horse hooves on Belgian block was replaced with the squeal of iron rails as electric trolley cars replaced the horse-cars of the New Bedford and Fairhaven Street Railway service. By 1900, the very earliest automobiles (with rubber tires) rumbled down the block and cobble streets. Finally, between 1925 and 1947 busses replaced the city’s electric trolleys, introducing a new, familiar white noise to the downtown landscape.

The hiss of cast-iron gas fixtures replaced whale oil lanterns along city streets in 1853, when the first gaslights were installed downtown. In turn, shortly following the establishment of the Edison Electric Illuminating Company in 1884, electric lights and carbon arc lamps supplanted gaslights at the end of the century. The disagreeable sound produced by carbon arc lamps was only remedied in 1891 with the invention of a patented alternator by Nikola Tesla, then Edison’s rival.

As the whaling industry began to decline, the New Bedford Railroad extended its tracks in 1876 to capitalize on increased traffic at the steamship wharf. The chug of steam engines entered the downtown soundscape as trains whisked bales of cotton to the mills at the city’s North and South Ends.

The representative pillars of New Bedford’s wealth changed too; the bells of ship masts and church steeples gave way to the churn of brick smokestacks as New Bedford’s economy entered a new industrial age, shifting away from whaling toward crude oil refinement and textile production.

NPS Photo/C. Beagan, 1997

Since the establishment of New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park in 1996, the park has served as a model for partnership and community collaboration, working with partners to preserve, protect, and interpret resources associated with the history of whaling. Currently, the park is collaborating with a team of local and state partners to improve the visual and pedestrian connections between the historic downtown and the working waterfront, which were cut-off in the early 1970s with construction of Route 18 and MacArthur Drive. Repaving is employing new hardscape materials that are universally-accessible and compatible with the historic character of the landscape.

Next time you're in a national park, take in the soundscape. Chances are the sounds hidden in plain sight will reveal stories of the cultural landscape. Might the wind you hear whispering through the trees be apple trees tended by Japanese-American internees in the Manzanar War Relocation Center in the 1940s (now Manzanar National Historic Site); the crunch of the trail underfoot be that laid by Civilian Conservation Corps workers on Mount Desert Island in the 1930s and early 40s (part of Acadia National Park); or the birdsongs be the soft call of the nēnē, the Hawaiian state bird saved from extinction through the efforts of Herbert Shipman at ‘Āinahou Ranch in the early twentieth century (now part of Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park)?

Visiting this Landscape

NPS Photo

You can find events, more details about the park, and help planning your visit at the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park website.

Contact: (508) 996-4095

Last updated: August 15, 2017