As time capsules of ancient life in the Southwest, pack rat middens reveal the relationships of people and construction to a changing climate.

NPS/Chaco Culture National Historical Park

Pack rats form shelters using environmental debris, such as sticks, leaves, and animal dung. They refurbish their nests, adding layer upon layer of new nest materials. Over hundreds or thousands of years, the pack rat's shelter dries out in the arid Southwestern climate. It forms a rock-hard mass of ancient feces and urine, as well as the seeds and plant matter they contained.

Because pack rats carried bits of pottery, twine and other artifacts from nearby human settlements into their shelters, the stratified middens also capture cultural history at a point in climatic time. Radiocarbon dating of the pack rats' middens enables scientists to create a chronology for the relationships between people, deforestation and resource depletion, and climatic changes. To do so, they evaluate the types of species that existed in the area, its population levels, and the time period when they existed.

In this way, scientists know that climate had an impact on the locations and use of ancient human settlements. Until about 11,000 years ago, the inhabitants lived in a woodland forest. The contents of pack rats' middens shows that local tree resources, including ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, juniper, pinon, and scrub oak, disappeared in the time, as a result of major cyclical drought. As the climate dried out, the woodland forest began to disappear.

Since at least 200 to 300 C.E., the ancient peoples in the Chaco Region drew on the trees for lumber to build their settlements, and the changing climate affected what and how they accessed timber resources. To be sure, however, the climate was not solely to blame for deforestation. During the 10th–12th centuries, people in the Chaco Region experienced a period of population growth leading to a construction boom. The trees couldn't grow fast enough to keep up with their logging.

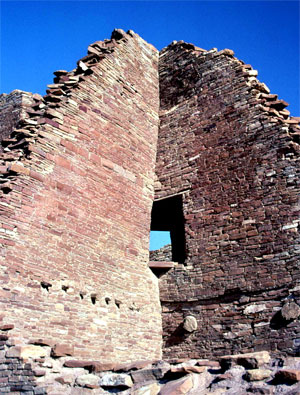

In response, the Chaco people gathered necessary timbers from farther and farther away, such as the mountains 50 to 60 miles to the west and south. Working without draft animals, the loggers hauled back over 200,000 logs of ponderosa pine, spruce and fir. By analyzing isotopes of strontium, researchers pinpointed that the Chaco builders were acquiring logs from Chuska Mountains and the San Mateo Mountains. From about 850 to 1100 years before present, they built the monumental masonry great houses of Pueblo Bonito, Una Vida, and Penasco Blanco, followed by Hungo Pavi, Chetro Ketl, and dozens more others. We can still see many of these structures today at the Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

Sometime between 800–750 years before the present, the people of Chaco Canyon dispersed in all directions to areas with more permanent water and agricultural potential. Archeologists believe that several factors were to blame—climate change being one, because it affected everything from agriculture to water supply to resource availability. The enormous monumental buildings required a vast amount of highly expensive roofing timbers to span large rooms designed to be 3 and 5 stories in height. To maintain this style of construction, they shifted the center of the culture from Chaco Canyon, to smaller "centers" located closer to the essential resources.

Last updated: July 20, 2022